You are here

Europe’s Tackling of ‘Root Causes’ of African Migration Has a Mixed Record

Returned migrants participate in development work in Burkina Faso. (Photo: IOM/Alexander Bee)

Amid unprecedented arrivals of migrants and refugees in 2015, the European Union’s executive branch announced an ambitious plan to tackle irregular migration at the source. At the heart of the strategy to address the “root causes” of migration was development assistance, particularly in Africa. This continent is not the primary origin of migrants and asylum seekers in Europe, but was where European policymakers saw population growth, lack of economic opportunity, and violent conflict as long-term triggers for future unchecked irregular migration. That November, the European Commission codified the effort in the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF), which over the next five years would support more than 250 migration- and displacement-related programs totaling 4.8 billion euros across 26 countries. The last of the money is scheduled to be committed by the end of 2021, and the fund will be succeeded by a new development mechanism with a small focus on migration, the Neighbourhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI).

Creation of the EUTF mirrored broader global interest in addressing poverty, poor governance, and insecurity as the underlying drivers of irregular migration. According to this logic, development assistance remedying those issues would reduce the incentive for people to migrate and obviate the need for aggressive migration controls at national borders. The notion has continued to gain popularity, although some scholars criticize it for underestimating the necessary amount of funding and ignoring Western policies that contribute to instability in migrants’ origin countries, such as military interventions or environmental degradation. Recently, U.S. President Joe Biden has offered a similar argument in calling for his country to provide $4 billion in aid over four years to Central American countries that are the origins of most asylum seekers and other migrants arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Data show that irregular migration from Africa to Europe has declined since the EUTF was unveiled, but there are reasons to question whether it was the primary reason for that decline. It is nearly impossible to prove causation, but evidence suggests that the fund has only modestly altered foundational economic and social factors driving migration, and has instead increased the ability of governments and others to surveil, control, and at times abuse migrants at or within their borders.

This article examines how the European Union has employed development assistance in Africa to advance aspects of its external migration policy. It starts with an overview of the bloc’s philosophy on the role of aid in migration and then focuses on the particulars of the EUTF. It argues that the assistance has been used for more than helping improve Africans’ social and economic well-being, but also to halt migratory movements and as a way to negotiate cooperation with countries of origin and transit. Taken together, these uses of aid have left the European Union’s ambitions to curb irregular migration only partially realized, in part because addressing the root causes of migration is a long-term endeavor far beyond the ability of an “emergency,” short-term mechanism.

The Changing Strategy of EU Migration and Development Policy

The EUTF is just one instance of the European Union using development assistance to manage external migration. The bloc’s approach has been inconsistent, at times viewing development as a means to deter immigration and other times viewing migration as a method to spur development. In 2002, the European Council set a long-term goal of using development programs to address root causes of migration. EU bodies subsequently created myriad initiatives and instruments to suppress irregular migration, most of which drew funding from the European Union’s development assistance budget.

Soon, however, the logic would flip, and European policy would be heavily influenced by the so-called migration-development nexus. Backed by migration advocates and the United Nations, sending-state governments argued that migration was an intrinsic driver of development in poorer origin countries. Indeed, estimated remittances from emigrants and others exceed official development aid by a factor of three, and advocates argue these streams have been more effective in reducing poverty and spurring growth than unwieldy assistance programs.

EU leaders proved receptive to this narrative, motivated in part by their countries' aging populations, low fertility rates, and needs to secure a sustainable labor force. Although avenues for legal migration have mostly been the remit of individual Member States, the European Union funded projects to facilitate legal movement from low- and middle-income countries via efforts such as the Aeneas program, which ran from 2004 to 2006. Frameworks in 2005 and 2011 known as the Global Approach to Migration and the Global Approach to Migration and Mobility promoted positive effects of migration such as skills-sharing and financial remittances. And in 2013, the European Commission argued that policymakers should collaborate globally to strengthen the development-migration nexus. Over the course of a decade, the European Union gradually positioned itself as a champion of migration and mobility.

Europe’s approach was complicated by the more than 1 million asylum seekers and other migrants who arrived in 2015. As the numbers of arrivals climbed, Brussels fixated on stemming the flow of migrants at their origins. Rather than framing migration and development as complementary, its dominant narrative shifted back to the earlier view that poverty and conflict were root causes of migration. Its immediate goal became keeping would-be migrants from leaving their origin region. Migration-oriented development assistance was retooled to meet this need.

Improving Conditions in Countries of Origin

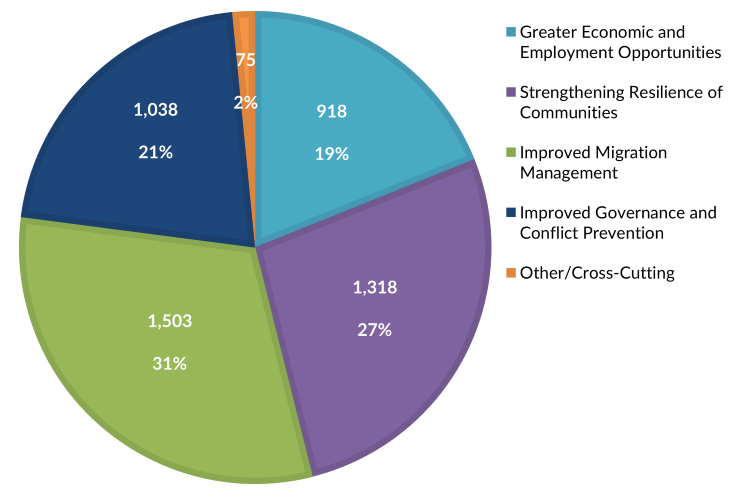

It was in this context that the EUTF was established in November 2015, focusing on North Africa, the Horn, and the Sahel region. The fund pursues four main strategic objectives targeting economic, social, and security drivers of irregular migration (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa Funding by Strategic Objective, in Millions of Euros, 2020

Source: European Commission, 2020 Annual Report: EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (Brussels: European Commission, 2021), available online.

As of the end of 2020, approximately one-fifth (918 million euros) of EUTF funds had been dedicated to programs promoting greater economic and employment opportunities in origin countries, the least of any objective. This included vocational training, small business support, and other assistance targeted particularly at young people and vulnerable groups.

The EUTF intervention logic rests on data suggesting employment, particularly for youth, discourages emigration. But training does not necessarily lead to jobs, particularly in rural areas and poorer countries with little demand for more skilled labor. This has been a challenge for the fund’s programming, which tends to provide only weak systemic support to employers and industries that would spur more hiring. A European Commission-ordered midterm evaluation by GDSI in October indicated that economic opportunities resulting from EUTF assistance have yet to prove sustainable, casting doubt on their ability to provide true alternatives to migration. As EUTF-funded programs end, young, unemployed ex-beneficiaries might instead decide to invest their skills and earnings in migrating, including toward Europe.

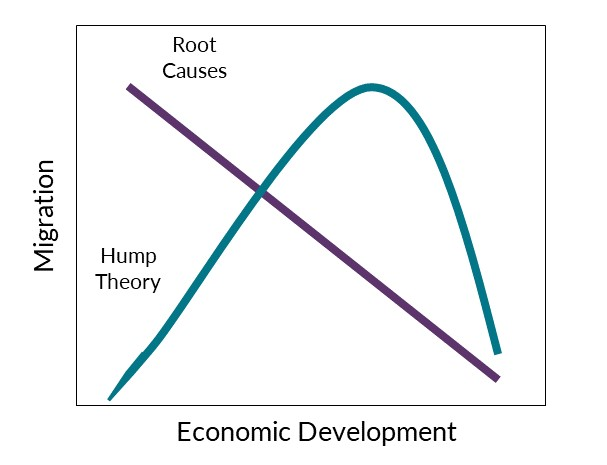

More nuanced understandings of migration and development such as the so-called hump theory posit that higher incomes can prompt emigration by reducing the cost of relocating, at least until a critical threshold—modeled to be approximately U.S. $7,000-$8,000 per year (purchasing power parity, 2000 prices)—when the benefits of migration drop off (see Figure 2). The fact that per capita incomes in most African countries are well below this threshold might suggest that more economic opportunity development programs for individuals could lead to greater emigration over the long term, including to Europe, therefore running counter to the stated goal of much EUTF programming.

Figure 2. Stylized Theorized Relationships between Economic Development and Migration

Source: Developed by the author.

Non-Economic Drivers

Economic root causes of migration are just one target of EUTF funding. Research also points to migrants’ social connections, aspirations for opportunities that exist elsewhere, and feelings of stagnation as issues affecting the propensity to migrate. Two EUTF strategic objectives focus on these types of systemic drivers such as poor governance and a lack of social services. Unlike increasing economic well-being alone, sending countries’ institutions and governance can be more likely to reduce pressures to migrate.

Combined, almost half of EUTF funding (2.3 billion euros) as of 2020 went to projects under its two strategic objectives of improved governance and conflict prevention, and strengthening resilience in countries of origin and transit. Among other things, projects in these categories aim to address human-rights abuses, improve rule of law, and increase access to basic social services such as health care, education, food, water, and sanitation. This constitutes critical support to many forcibly displaced communities.

Yet the impact EUTF resilience support has on future irregular migration is both modest and unsustainable, according to the October 2020 midterm evaluation. Due in part to its short-term nature, the EUTF “is not an appropriate vehicle for addressing root causes of major societal problems,” the evaluation concluded. Further, significant resilience funding has gone to protracted displacement crises in countries such as Burkina Faso, Somalia, and South Sudan, which are not major sources of irregular migration to Europe. Although it may be an important initial step in advancing social protection and institutional reform in Africa, current funding is insufficient to sustainably reduce irregular migration by tackling root causes alone.

Aid to Halt? Controlling Irregular Migration beyond EU Borders

For all the emphasis on tackling root causes, the EUTF has also been used to treat the symptoms of irregular migration, such as porous borders at Europe’s southern periphery and along migratory routes. Nearly one-third of its funding (1.5 billion euros as of 2020) has gone to improving migration management, which since 2018 has been the best-funded EUTF objective. It is also the only objective with programs in all 26 EUTF countries, covering efforts to meet international standards at migrant detention and disembarkation sites and assisting returned migrants. The full amount earmarked for migration management is likely to be larger; according to the author’s calculations, more than 10 percent of funding under the strategic objective of improving governance and preventing conflict specifically addresses migration governance through activities such as enhancing border surveillance cooperation, tackling smuggling networks, and technical trainings for border staff.

In 2015-16, Libya was the primary launching point for people attempting the often-perilous journey from Africa to Europe. It is also the site of programs adding up to approximately 20 percent (nearly 310 million euros) of EUTF funding for improving migration management. In one of the largest projects, 90 million euros have been used to improve detention centers, assist migrants’ return, and help communities affected by migration, among other efforts. Another 42 million euros have been allocated to enhance the operational capacity of Libyan government authorities, including building the capacity of maritime and land border surveillance, training for halting illegal border crossings, and strengthening search-and-rescue activities at sea. This funding has been a primary mechanism for the European Union’s migration-related assistance to Libya, although it has also spent 98 million euros under the European Neighbourhood Instrument and additional nondevelopment support under Europe’s Common Security and Defense Policy.

Amid these programs and other interventions, crossings through the Central Mediterranean route connecting Libya to Italy and Malta declined by 81 percent between 2017 and 2018, and continued to stay low in subsequent years.

At the same time, hundreds of thousands of migrants and asylum seekers trapped in Libya have had no way forward. Despite EUTF programs to improve reception for migrants returned to Libya by the Libyan coast guard, which the European Union has supported, many have been subjected to brutal conditions and face violence, extortion, and forced labor akin to slavery. Journalists have documented that significant amounts of money have been diverted to militias, traffickers, and others who torture and abuse migrants.

Similar concerns have manifested elsewhere. In Sudan, for instance, EU agencies temporarily suspended support for an anti-criminal and trafficking coordination center in the wake of concerns that it could be emboldening repression following the 2019 ouster of President Omar al-Bashir.

Repercussions of Using Aid to Control Migration

Border controls may simply divert migration rather than halt it entirely. Increased barriers along the Central Mediterranean route have in some cases driven migrants to seek alternatives to reach Europe. While arrivals to Italy plummeted since the peak of the crisis, 2020 saw more than 40,000 people arrive by sea in Spain, including the Canary Islands, a five-fold increase over 2016.

Europe’s focus on controlling migration from Africa may have affected its broader development assistance priorities, potentially prioritizing support to countries strategically relevant for migration instead of on the basis of development need. Driven by the urgency of the migration situation in 2015, an assessment by European nongovernmental organizations found many EUTF projects were approved and implemented too quickly, without consulting local communities and cohering with African national development plans or other EU development goals. Oxfam has criticized the fund for measuring progress by its impact on irregular migration, potentially viewing an individual’s emigration as a failure regardless of the security and economic context.

EU-backed migration controls may even hamper intra-African mobility, which is widely recognized as a driver of the continent’s economic development. Slightly more than half of African migrants move to other African countries, and African leaders have made efforts to eliminate barriers to intracontinental movement. Yet in the EUTF’s early years, West Africans with free-movement rights in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) complained of involuntary returns when the criminalization of migrant smuggling led to indiscriminate pushbacks from Niger.

Aid to Haggle: Migration Cooperation as Leverage

Whether assistance is used to reduce incentives to migrate or increase the barriers to doing so, Europe has also deployed its aid to attract African cooperation on the issue. This has particularly been the case since the 2015-16 period, when the European Commission has aimed to use both carrot and stick to, in its words, “reward those countries willing to cooperate effectively… on migration management and ensure there are consequences for those who do not cooperate.”

Governments in Africa and elsewhere have reason at times not to cooperate, perhaps preferring emigrants’ remittances from wealthy countries or choosing to view migration as a pressure relief valve for high unemployment. In the past, governments in Tunisia, Libya, and elsewhere have deliberately withheld migration cooperation to extract concessions from Europe. Generally, however, partnerships have prioritized EU interests in countering irregular migration over those of African nations or migrants themselves, which may include liberalizing trade or increasing legal migration to Europe.

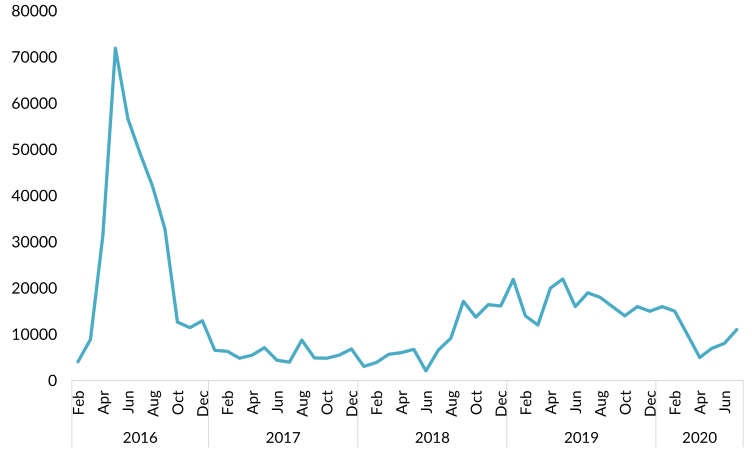

Spotlight on the Sahara: Niger

Niger, a country generally praised for its cooperation with European interests, offers a useful lens for viewing this transactional policymaking and its mixed results. Niger is a major transit country for migration to Europe, and, after heavy EU lobbying, became the first West African country to criminalize migrant smuggling in 2015. The number of people passing through plummeted from a peak of 72,000 in May 2016 when authorities began cracking down. This drop is not necessarily proof of the law’s success, since there is evidence that many migrants simply adopted alternate routes and bypassed monitoring points. But migrants’ passage clearly declined amid heightened EU attention and funding.

Figure 3. Migrants Observed at Outgoing Flow Monitoring Points in Niger by Month, 2016-20

Source: International Organization for Migration, “Displacement Tracking Matrix – Niger,” accessed May 3, 2021, available online.

More than 272 million euros have gone to Niger-based projects under the EUTF, more than all but a few other countries. But the benefits have not always trickled down. While EUTF funding has supported government institutions and helped build centers for returning migrants, many Nigeriens say they have not benefited from this aid. For instance, industries related to both irregular and legal migration were a sizable source of income for many, yet there have been few meaningful attempts to replace the money lost when enforcement of the anti-smuggling law reduced overall mobility. Underlying factors of poverty, poor governance, climate change, and economic instability continue to persist, and movement restrictions due to COVID-19 have likely exacerbated the challenges. If Europe wishes to continue upholding Niger as a model, policymakers and development actors need to move beyond short-term interventions and focus on solutions to these long-term issues.

A Missing Link: Making Good on Legal Migration Promises

Prior to 2015-16, the European Union had begun laying a foundation for cooperation with developing countries based on well-managed, legal migration as a driver of development. Policymakers largely abandoned this approach as they scrambled to respond to the crisis, which was ironically the moment they needed cooperation most in order to return migrants to countries of origin. Across the five years of the EUTF, fewer than 450 people have benefitted from its legal migration and mobility programs, according to the fund’s monitoring data as of April, although visas are typically granted by individual Member States. Judging from the European Commission’s proposed New Pact on Migration and Asylum, the European Union seems poised to continue paying insufficient attention to legal pathways for non-European migrants seeking economic opportunity.

Development assistance will continue to be a tool for Europe to manage migration from outside the bloc. But its results have so far been mixed. Underlying economic, political, and security issues in migrants’ origin countries are unlikely to be foundationally upended by aid that is by definition temporary. And while stronger migration controls have some effect, they often push migrants and asylum seekers to seek dangerous alternate routes.

Only one-tenth of the upcoming NDICI instrument is formally devoted to migration issues. But critics say a nearly 10 billion-euro, unallocated “flexibility cushion” designed for unforeseen needs could be used for politically motivated migration priorities of the kind that characterized the EUTF.

Instead of repeating past experiences, European policymakers should consider decoupling aid from activities that primarily halt irregular migration and scale up sustainable investments in public services and alternative livelihoods. They could also follow through on longstanding promises to use aid to support safe and legal migration options for Africans, particularly within their region but also in some cases toward Europe. The European Union has piloted circular migration and mobility partnerships before and could take cues from those experiences, while working with individual Member States to advance effective legal pathways and supporting regional mobility within the African continent. Other destination countries interested in addressing root causes of migration could also learn from the EUTF’s experience.

Support for legal pathways would help achieve the balance and reciprocity in EU-African migration cooperation necessary for EU countries to humanely manage returns and negotiate repatriation agreements. It might even address Europe’s worsening labor shortages. Most importantly, legal economic migration opportunities offer African migrants more safe and dignified choices for their future.

Sources

Bermeo, Sarah Blodgett and David Leblang. 2015. Migration and Foreign Aid. International Organization 69: 627–57. Available online.

Berthélemy, Jean-Claude, Monica Beuran, and Mathilde Maurel. 2009. Aid and Migrations: Substitutes or Complements? World Development 37 (10): 1589-99.

Brenner, Yermi, Robert Forin, and Bram Frouws. 2018. The “Shift” to the Western Mediterranean Migration Route: Myth or Reality? Blog post, Mixed Migration Center, August 22, 2018. Available online.

Carrera, S., R. Radescu, and N. Reslow. 2015. EU External Migration Policies: A Preliminary Mapping of the Instruments, the Actors and their Priorities. Brussels: EURA-net.

De Guerry, Olivia, Andrea Stocchiero, and CONCORD EUTF Task Force. 2018. Partnership or Conditionality? Monitoring the Migration Compacts and EU Trust Fund for Africa. Brussels: CONCORD Europe. Available online.

Clemens Michael, Helen Dempster, and Kate Gough. 2019. Promoting New Kinds of Legal Labour Migration Pathways between Europe and Africa. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. Available online.

Clemens, Michael A. and Hannah M. Postel. 2018. Deterring Emigration with Foreign Aid: An Overview of Evidence from Low-Income Countries. Population and Development Review 44 (4): 667-93. Available online.

Disch, Arne et al. 2020. Mid-Term Evaluation of the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Stability and Addressing Root Causes of Irregular Migration and Displaced Persons in Africa 2015-2019. Brussels: European Commission. Available online.

European Commission. 2002. Integrating Migration Issues into the EU's External Relations. Press release, December 3, 2002. Available online.

---. 2011. The Global Approach to Migration and Mobility. Brussels: European Commission. Available online.

---. 2013. Maximising the Development Impact of Migration: The EU Contribution for the UN High-Level Dialogue and Next Steps towards Broadening the Development-Migration Nexus. Brussels: European Commission. Availanle online.

---. 2015. A European Agenda on Migration. Brussels: European Commission. Available online.

---. 2016. On Establishing a New Partnership Framework with Third Countries under the European Agenda on Migration. Brussels: European Commission. Available online.

---. 2017. On the Delivery of the European Agenda on Migration. Brussels: European Commission. Available online.

---. 2021. 2020 Annual Report: EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. Brussels: European Commission. Available online.

---. 2021. EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa - State of Play and Financial Resources. Updated February 12, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. EU Trust Fund for Africa - Our Projects. Accessed March 21, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. EU Trust Fund for Africa Results Framework. Accessed March 21, 2021. Available online.

European Council. 2015. Valletta Summit, 11-12 November 2015: Action Plan. Valletta: European Council. Available online.

Faini, Riccardo and Alessandra Venturini. 1993. Trade, Aid and Migrations: Some Basic Policy Issues. European Economic Review 37 (2-3): 435-42.

Howden, Daniel and Giacomo Zandonini. 2018. Niger: Europe’s Migration Laboratory. The New Humanitarian, May 22, 2018. Available online.

Knoll, Anna and Andre Sheriff. 2017. Making Waves: Implications of the Irregular Migration and Refugee Situation on Official Development Assistance Spending and Practices in Europe. Maastricht: ECDPM. Available online.

Koenig, Nicole. 2017. The EU's External Migration Policy: Towards Win-Win-Win Partnerships. Berlin: Jaques Delors Institut Berlin. Available online.

Lavenex, Sandra and Rahel Kunz. 2008. The Migration–Development Nexus in EU External Relations. European Integration 30 (3): 439-57. Available online.

Lixi, Luca. 2017. Beyond Transactional Deals: Building Lasting Migration Partnerships in the Mediterranean. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

Michael, Maggie, Lori Hinnant, and Renata Brito. 2019. Making Misery Pay: Libya Militias Take EU Funds for Migrants. Associated Press, December 31, 2019. Available online.

Papademetriou, Demetrios G. and Kate Hooper. 2017. Building Partnerships to Respond to the Next Decade’s Migration Challenges. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

Raty, Tuuli and Raphael Shilhav. 2020. The EU Trust Fund for Africa: Trapped Between Aid Policy and Migration Politics. Oxford: Oxfam International. Available online.

Slagter, Jonathan. 2019. An “Informal” Turn in the European Union’s Migrant Returns Policy towards Sub-Saharan Africa. Migration Information Source, January 10, 2019. Available online.

Sørensen, Ninna Nyberg. 2012. Revisiting the Migration–Development Nexus: From Social Networks and Remittances to Markets for Migration Control. International Migration 50 (3): 61-76. Available online.

Stalker, Peter. 2002. Migration Trends and Migration Policy in Europe. International Migration 40 (5): 151-79. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2021. Spain - Land and Sea Arrivals - December 2020. Fact sheet, UNHCR, Geneva, January 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Operational Portal – Refugee Situations. Last updated April 18, 2021. Available online.

Willis, Tom. 2019. EU Suspends Migration Control Projects in Sudan amid Repression Fears. Deutsche Welle, July 22, 2019. Available online.

Wunderlich, Daniel. 2010. Differentiation and Policy Convergence Against Long Odds: Lessons from Implementing EU Migration Policy in Morocco. Mediterranean Politics 15 (2): 249-72. Available online.

World Bank Group. 2018. Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook - Transit Migration. Migration and Development Brief No. 29, Washington, DC: World Bank. Available Online.

---. 2020. Annual Remittances Data, October 2020 update. Available online.