Limited English Proficient Workers and the Workforce Investment Act: Challenges and Opportunities

As the U.S. Congress considers reauthorization of the Workforce Investment Act (WIA) of 1998, policymakers and immigrant advocates are pushing for a variety of changes meant to better help Limited English Proficient (LEP) immigrants access the employment and training services necessary to enter into or advance within the U.S. labor market. With a number of proposals floated to rethink the WIA-funded workforce and adult education systems, the debate highlights the challenges LEP workers face in earning family-sustaining wages and effectively participating in a changing labor market.

Though perhaps little recognized as such, WIA represents one of the most important immigrant integration programs at the federal level both in size and scope, and its reauthorization has key implications for the integration of immigrant workers into the U.S. economy and society more broadly.

Reauthorization — which is likely to fall flat in the current Congress (as it has a number of times since the law technically expired in 2003) but may be taken up by future Congresses — has general support from both sides of the aisle. Stark disagreement remains on how to revamp the system, however, chiefly for reasons having nothing to do with immigrant workers. In the meantime, the employment and training needs of foreign-born workers, which are often different than those for the native born, are quickly changing and states face significant limitations in serving this population through federally funded programs.

There were 23 million immigrants in the U.S. civilian labor force in 2010, accounting for one in six workers ages 16 and older — a figure that has roughly doubled since 1990. Within the immigrant labor force, nearly half speak English less than "very well" (as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau) and are classified as "Limited English Proficient," a language barrier that affects their employability and wage-earning potential. Though the WIA system is the core source of federal support for workforce training, English as a Second Language (ESL) instruction, and other adult education programs, the current design has created barriers for LEP workers seeking workforce services. In particular, misalignment in goals, program services, and performance accountability mechanisms across WIA-funded programs has made it difficult for these workers to obtain the language and work training services they need to advance in the workforce. At the same time, the LEP population continues to grow. In 2000, about 17.8 million U.S. adults, or 8.5 percent of the population, had limited English proficiency. Today, there are roughly 22.5 million LEP adults, accounting for 10 percent of the U.S. adult population and 9 percent of the labor force.

At the time of WIA's passage in 1998, policymakers were focused on "work-first" policies popularized under welfare reform and so emphasized rapid re-employment and the acquisition of short-term skills as core training approaches. Since then, labor force demand for middle-skilled jobs — which require longer-term education and training — has grown. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports that one-third of all job openings and nearly half of all new jobs created between 2008 and 2018 will require a postsecondary degree or credential. Nationally, immigrants accounted for 49 percent of workers without a high school degree and 15 percent of college-educated workers ages 25 and older. (Just 11 percent of all U.S.-born adults lack a high school diploma or GED, compared to 32 percent of immigrant adults.) California, for example, ranked first for the highest share of immigrants among low-educated workers (80 percent) and the highest share of immigrants in the college-educated workforce (30 percent). LEP adults ages 18 and older account for 39 percent of all low-skilled workers. In California and Texas, the two states with the largest LEP populations and largest state economies, more than half of low-skilled workers have limited English proficiency (66 percent in California, 53 percent in Texas). Furthermore, 47 percent of LEP adults lack a high school diploma.

Demographic and economic changes have created pressure for states and localities to develop training and education programs to allow workers to upgrade their skills and obtain credentials to fill jobs in high-growth sectors such as health care and information technology. For these opportunities to become available to a significant number of LEP workers, the number of WIA-funded training programs that provide integrated workforce training and English-language instruction would need to be greatly expanded.

This article provides an overview of WIA's structure relating to employment and training services for LEP workers, examines Department of Labor (DOL) data showing the extent to which LEP workers have accessed the system since its inception, and reviews key themes of relevance in the reauthorization debate.

Challenges to the Workforce Investment Act (WIA) of 1998

WIA's Title I and Title II provide funding for different aspects of workforce training and education. Title I funds employment and training initiatives, and Title II funds adult education and ESL instruction.

Congress has continued to appropriate funds for WIA despite its expiry in 2003. Funding has been on a general decline, however, amid failed attempts to reauthorize the law and growing bipartisan criticism of WIA's structure and implementation. Between fiscal years (FY) 2001 and 2010, funding for employment and training initiatives (Title I) declined 30 percent, according to inflation-adjusted calculations by the National Skills Coalition. In FY 2010 — the latest year for which data are presented below — Congress appropriated $2.97 billion for workforce training programs, which decreased to $2.62 billion in FY 2012. Between FY 2001-10, federal funding for adult education (Title II) declined by about 16 percent, with Congress appropriating $628.2 million for adult education and ESL instruction in FY 2010 and $606.3 million in FY 2012. For LEP workers who require services under both titles to become job ready, the decline in funding has presented challenges to obtaining basic ESL courses, which are often oversubscribed, as well as appropriate training opportunities.

Title I's employment and training system provides funding to states for workforce services for three key populations: adults, youth, and dislocated workers (individuals who have been laid off, fired, or were self-employed but can no longer work because of economic conditions). Dislocated workers are treated as a separate population under Title I because of their more immediate need for employment, compared with the general adult population, which may seek employment and training services to upgrade their skills while current employed. The law allows some flexibility for states and localities to devise strategies to serve these populations, although they must adhere to the same performance accountability and programmatic standards, and funding guidance regardless of their approach. Authority for implementation flows down from DOL's Employment and Training Administration, through governors and state-level workforce investment boards, to local workforce boards, and finally to One Stop Centers that offer services.

State workforce boards are tasked with developing statewide strategic plans for meeting labor market needs for a diversity of workers, while local workforce boards execute these plans at the community area. These local boards select One Stop operators and eligible training providers, coordinate linkages with local economic training and employer organizations, and promote employer involvement in all areas of the local system. Finally, One Stop Centers are the place where workers can receive services to help them upgrade their skills or find employment.

One Stop Center services for adults and dislocated workers are divided into three categories: core, intensive, and training services. Core services are available to all individuals and include self-directed job searching or assistance with filing unemployment claims. Intensive services (as well as training services) require registration and are available to legal residents and include activities such as a skills assessment, career counseling, and short-term pre-vocational services. And training services include occupational skills and on-the-job training, and sessions offered through institutions of higher education and community-based organizations and apprenticeships. Individuals deemed eligible by One Stop Center staff are given training accounts to seek services from local training providers.

Separately, Title II is administered by the Department of Education's Office of Vocational and Adult Education and provides funds for adult education, literacy, and ESL classes, targeting individuals 16 years or older without a high school diploma or basic workplace literacy skills. Organizations providing such activities include community colleges, public schools, and community-based organizations.

There is broad consensus among analysts, academics, and policymakers that the legal and administrative structure of the WIA system has created service access hurdles for LEP workers and others with training and education needs. In particular, the mandate that One Stop Centers serve as the single point of access for different federally funded employment, training, and adult education programs has not been met. This is largely due to disincentives One Stop Center staff — and state and local workforce boards trying to show positive performance outcomes — face when deciding what services to refer LEP workers.

Titles I and II have separate performance accountability goals, despite the fact that LEP workers and others require services under both to become job-ready. Performance accountability measures are not aligned across titles, which, critics argue, has created disincentives to serving LEP workers. States are required to negotiate performance levels for Titles I and II with the Departments of Labor and Education separately, despite both sets of services being mandated under WIA to be available through the One Stop system. Critics argue that pressures to meet performance levels enter into states' determinations on how to serve LEP workers. States and in turn their contracted service providers may be sanctioned for not meeting negotiated performance levels, thus creating incentives to direct Title I funds to serve less needy populations — a practice known as "creaming" — at the expense of difficult-to-serve populations, such as LEP workers.

Title I's performance measures emphasize rapid re-employment and improvements in earning — measures of performance difficult for LEP individuals to quickly achieve. Specifically, LEP individuals receiving training may not be able to acquire English skills fast enough to keep pace with the training and get hired for new work, and may also have difficulty retaining employment long enough to be counted as a positive performance outcome. Further, studies have found that One Stop Center staff cognizant of the difficulty LEP individuals have in meeting performance targets may intentionally avoid placing eligible individuals into training as these LEP individuals may not successfully complete the training and thus not be counted as a positive performance outcome. A 2002 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that "states reported that the need to meet these performance levels may lead local staff to focus WIA-funded services on job seekers who are most likely to succeed in their job search…"

Meanwhile, Title II's performance accountability measures emphasize improvements in literacy, including English-language acquisition, as well as placement or retention in postsecondary education, training, or employment. Given the overlapping but separate performance measures in Titles I and II, studies of One Stop Centers have noted confusion about whether to place LEP individuals in Title I or II programs, with the tacit acknowledgement that meeting some Title II goals may be easier than Title I goals. The result is that immigrants may be placed in English language courses without a workforce training component, limiting the potential success in the transition to employment.

LEP Workers' Access to WIA Programs

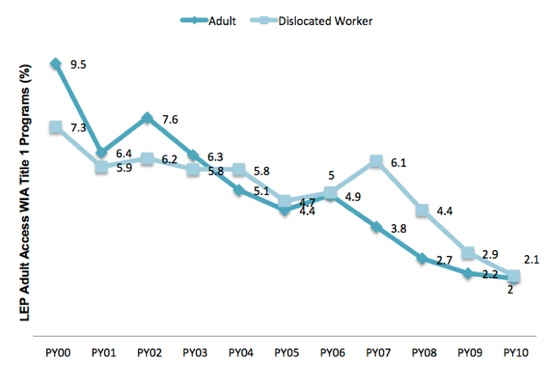

Data from DOL on enrollment in Title I programs show that the share of LEP workers among all workers receiving training is on the decline. Meanwhile, co-enrollment in Title II programs for LEP adults and dislocated workers has increased in recent years. (The data only highlight the extent to which co-enrollment in ESL or other adult basic education course is occurring for LEP workers.)

Most adults or dislocated workers who access WIA Title I employment and training services only use "core" services, which are typically self-directed and do not require registration. For example, in program year (PY) 2010, about 803,000 adults accessed Title I core services, while 497,000 received intensive or training services. Of all individuals receiving intensive or training services, LEP adults account for a small share despite their over-representation among the low-skilled labor force. LEP adults represented 2 percent of all adults receiving intensive or training services in PY 2010, compared to 9.5 percent in PY 2000 (see Figure 1).

The percent of LEP adults served under Title I was highest in PY 2002, when 14,668 accessed intensive or training services (see Table 1). This population reached a low in numbers served in PY 2007, when 8,400 LEP adults accessed intensive or training services.

Although the scale of the decline has been less dramatic than for LEP adults, dislocated workers with limited English proficiency also have seen a decline in their representation among those receiving intensive or training services.

|

Figure 1. Share of LEP Population Served in WIA Title 1 Adult or Dislocated Worker Programs with Intensive or Training Services, (%) PY 2000-10

|

||

|

|

Table 1. Number of LEP Adults Accessing WIA Title I Adult or Dislocated Worker Programs with Intensive or Training Services, PY 2000-10

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

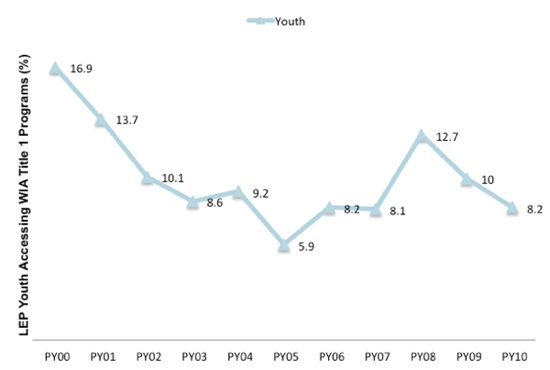

The share of LEP youth served has changed over time as well. In PY 2000, 16.9 percent of all youth served had limited English proficiency. By comparison in PY 2010, 8.2 percent were LEP. Compared to the adult and dislocated worker programs, the WIA youth program has served relatively high shares of LEP youth over time; however, the number of LEP youth receiving intensive or training services has declined dramatically — from a high of 16,369 in PY 2002 to a low of 8,615 in PY 2005 (see Table 2).

|

Figure 2. Share of LEP Youth Accessing WIA Title I Programs with Intensive or Training Service, (%), PY 2000-10

|

||

|

|

Table 2: Number and Share of LEP Youth Accessing WIA Title I Programs with Intensive or Training Service, Program Years 2000-10

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

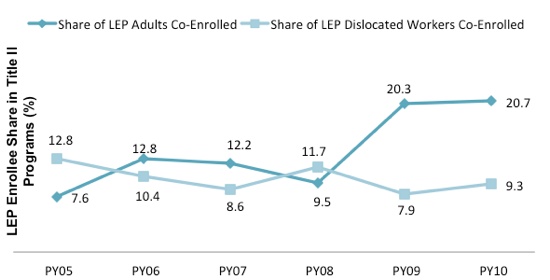

Data on co-enrollment with Title II programs (as measured by LEP adults and dislocated workers receiving adult education or ESL classes in combination with Title I training services) indicates that even as the share of LEP individuals receiving Title I services has declined over time, they are increasingly receiving Title I services in concert with adult education or ESL courses. While the quality of this combined training and education is not examined — or whether the two are integrated in a work environment, as many analysts agree is most effective — Figure 3 shows an increasing trend toward co-enrollment. Given existing evidence of the insufficient capacity of the Title II adult education and ESL system to meet instructional demand from LEP individuals, the increase in co-enrollment shows a growing awareness among One Stop Center staff — and the workforce boards that guide them — about the dual employment and language instruction needs of LEP workers. In recent years almost half of all individuals served under Title II programs were enrolled in ESL programs and many such classes in states with high concentrations of immigrant populations consistently reach full registration.

|

Figure 3. Share of LEP Adults and Dislocated Workers Co-Enrolled in Title II Programs,* (%), PY 2005-10

|

||

|

Current Debate Explored

While WIA reauthorization proposals circulating in Congress differ, they share three common themes and represent some consensus about how to address the systems' challenges: consolidate or better align programs and program funding and goals; establish common performance measures and strategic planning across Titles I and II; and change the role and representation of state and local workforce boards.

Within these themes, the role of LEP individuals and others with multiple barriers to employment (such as low-income individuals) has been hotly contested by public and private stakeholders. The following are changes within the existing proposals before Congress.

Consolidate or better align workforce programs, program funding, and goals. Citing a 2011 GAO report that identified 47 job training programs offered through nine federal agencies, several members of Congress are seeking to streamline WIA to eliminate redundancies. Proposals range from consolidation of programs and funding into a single block grant to give states flexibility to determine how to meet local training, education, and labor market needs, to multiple workforce investment funds being targeted to particular populations. Proponents of consolidation note that fewer funding streams that target broad populations would allow state and local governments to develop innovative approaches to serving their local labor market needs with less administrative burden. Others have argued for better alignment across WIA's Titles I and II to ease training access for different subpopulations (LEP workers, low-income workers, etc.) within adults, dislocated workers, and youth. Lifting current fund restrictions and tying workforce development to educational attainment are among the proposals being suggested to counterbalance calls for consolidation of the system as well as barriers to access under the existing system.

Establish common performance measures and strategic planning. Broad consensus exists about the need to align performance measures across Titles I and II. Calls for unified state plans would jointly report the goals and program approaches of the workforce training and adult education systems. Advocates for improving access for hard-to-serve populations have called for improvements to existing state planning proposals that would require states to detail how specific populations, such as LEP workers, will be served. Many states already include information about how they provide language access to LEP individuals through the One Stop system, but do not provide strategies for effective training and education services. Similarly, while there is consensus about the need to create common performance measures across both programs to eliminate disincentives to serving hard-to-serve populations, disagreement exists about what measures would be effective in demonstrating skills improvements. For example, some proposals include credential attainment within a specific time period as a common performance measure, reflecting the importance of certifications and postsecondary education to job success in the economy. While many welcome this clarification, others argue that interim gains in improved English proficiency or movement toward credential attainment are an important barometer of growth for those who need extra time to improve their skills. While there have also been calls to weight the performance of LEP individuals and other special populations differently, little evidence exists of what statistical models would be appropriate to capture relative performance.

Change the role and representation of state and local workforce boards. State and local workforce boards are comprised of members of the business community, mandatory state agency partners, labor unions, and community organizations. Advocates for greater inclusion of hard-to-serve populations argue that those groups' competing interests may sidetrack WIA's core goal to retrain workers to fill business demand and boost local economies. They point out that empowering the business community to shape local training and education systems will lead to the increased availability of sector partnerships and industry-led collaborations for targeted training. As a result, many proposals call for workforce board membership to be heavily weighted toward the business community. However, community-based organizations and immigrant advocates note that LEP individuals and others with multiple barriers to employment will be left out unless their needs are heard. They note that workforce boards' selection of training providers offered through the One Stop system should include organizations that understand the needs and availability of locally provided training services appropriate for LEP individuals. As well, many have called for increasing flexibility for local boards to award contracts if the board determines that a community or private organization has demonstrated effectiveness in serving individuals with barriers to employment.

Next Steps

As immigrant populations continue to spread to new destinations less equipped than the traditional destination states to provide services for the LEP population — and amid continued uncertainty over when federal and state budgets will rebound — the need to have a more responsive WIA system is likely to become more visible.

The nature of the current WIA reauthorization debate — in addition to the failures of previous attempts at reauthorization — highlights the complications and challenges of revamping the workforce training and adult education systems. While the debate has implications for many groups, LEP individuals — caught between the overlapping, but separate, missions of Titles I and II — stand to gain or lose in particular. Existing structural, funding, and political constraints continue to limit the ability of the system to meet the needs of LEP individuals.

Along the way, states and localities with rich nonprofit and community-based organization networks serving LEP populations have filled in service gaps left by Title I and Title II programs. The inability of the system to scale up to the need of diverse populations will have significant implications for not only these immigrant individuals and their families, but for the economy in general.

Sources

Capps, Randy, Michael Fix, and Serena Yi-Ying Lin. 2010. Still an Hourglass? Immigrant Workers in Middle-Skilled Jobs. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Capps, Randy, Michael Fix, Margie McHugh, and Serena Yi-Ying Lin. 2009. Taking Limited English Proficient Adults into Account in the Federal Adult Education Funding Formula. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Center for Asian American Advocacy. 2005. Bridging the Language Gap: An Overview of Workforce Development Issues Facing Limited English Proficient Workers and Strategies to Advocate for More Effective Training Programs. Washington, DC: Center for Asian American Advocacy. Available online.

National Council of State Directors of Adult Education. 2010. Adult Student Waiting List Survey. Washington, DC. Available online.

National Skills Coalition. 2011. Training in Policy Brief: Workforce Investment Act, Title I. Washington, DC. Available online.

Terrazas, Aaron. 2011. The Economic Integration of Immigrants in the United States: Long-and Short-Term Perspectives. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2006 and 2010 American Community Surveys. Accessed from Steven Ruggles, J. Trent Alexander, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Matthew B. Schroeder, and Matthew Sobek. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2010. Available online.

U.S. Department of Labor. Social Policy Research Associates data, 2001-10. Available online.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2009. Workforce Investment Act: Labor Has Made Progress in Addressing Areas of Concern, but More Focus Needed on Understanding What Works and What Doesn't. Washington, DC. Available online.