You are here

Tense Neighbors, Algeria and Morocco Have Divergent Migration Histories

Paintings of the Algerian and Moroccan flags on a brick wall. (Photo: iStock.com/Gwengoat)

Longstanding tensions between Algeria and Morocco have resulted in a series of standoffs since the countries’ independence from France in the mid-20th century. Their land border of more than 1,400 kilometers (nearly 900 miles), has been officially closed since 1994, and recent hostilities have disrupted not only relations between the two neighbors but also efforts at broader intra-African and intra-Arab connectivity. In 2021, Algeria broke off diplomatic ties over what it said were “hostile actions” by Morocco involving support for a separatist Berber group. It also closed its airspace to Moroccan planes, affecting flights towards hubs in Egypt and Tunisia that link Africa to other global regions. Previously, Morocco had normalized its relationship with Israel, a nation Algeria does not recognize, leading the United States to recognize Morocco’s sovereignty over the Western Sahara. The disputed territory has long been the source of consternation between the neighbors; Algeria has supported the separatist Polisario Front in its fight against Rabat. Earlier this year, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune said relations with Morocco had reached “the point of no return.”

Although the nations have much in common—including Muslim-majority populations, linguistic and cultural ties, a shared history of French colonialism, and similarly sized populations and economies—their relations have been continually defined by persistent low-grade conflict. The closed border has led to the flourishing of informal smuggling networks involving fuel, food, and illegal drugs, which in turn further exacerbate the tension between the countries and lead to mutual finger-pointing. Instead of cooperation on border control involving shared intelligence and joint operations, the countries have heavily invested in militarizing their borders, yet have to failed to halt illicit cross-border trade.

Algeria and Morocco are united in their desire to curb irregular arrivals of sub-Saharan African migrants. Yet here too, lack of cooperation undermines their efforts. Although walls and trenches have made migration riskier, deadlier, and more costly, they have not blocked the inflow of migrants, who often are headed towards the European Union. Meanwhile, the securitization has further marginalized border communities, which have often come to rely on the smuggling trade in the absence of robust development projects.

The Algerian and Moroccan histories of emigration, meanwhile, are a study in contrasts, partly due to divergent policies after independence. While both were part of the French empire, the two countries had differing approaches towards emigrants and the political threats they could pose, leading France to be the primary destination for most Algerian emigrants while Moroccans tend to be more evenly distributed across Western Europe.

This article provides an overview of migration policy in Algeria and Morocco, highlighting similarities and differences between the bitter rivals. While both countries have sought to limit migration from south of the Sahara, their motives have been different. Morocco has largely acted in response to EU pressure, while Algeria’s policy is more domestically focused. And while both states shared authoritarian tendencies and a historical suspicion of emigrants, economic logic has triumphed in Morocco, which has sought to manage outflows, while Algeria has acted with a tighter fist.

Hard Borders for Different Reasons

Sub-Saharan migrants headed mostly for Europe have posed challenges for Algeria and Morocco since the 1990s. Both have viewed this migration pattern as a security concern and adopted similar practices to criminalize migrants’ passage. Yet they did so for different reasons. Algeria’s approach emanated from domestic security concerns, whereas Morocco has been a more willing participant in EU programs that offer development assistance in exchange for more robust migration management.

Algeria has long opposed acting as gendarmerie of the European Union and has exhibited significant caution in collaborating with the bloc, especially on migration control initiatives and activities with the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex). Algeria’s stance has been possible in part because of the country’s large supply of natural resources, which has given the ruling elite space to maneuver. This rather comfortable financial situation has enabled Algeria to reject millions of euros the European Union offered to support Algeria’s migration management infrastructure. As such, the anxiety that many sub-Saharan migrants will settle in Algeria has led the government to view the issue primarily as a local security concern to be handled without foreign interference.

Morocco, on the other hand, does not have similar oil and gas deposits, historically has had a slightly smaller economy, and has been more amenable to migration cooperation with the European Union. While it is difficult to track the various funding mechanisms, the European Union had sent hundreds of millions of euros to support Morocco’s border control, integration, and other migration-related infrastructure. Since 2018, the European Union has used mechanisms such as the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa to release vast sums of funding for Morocco to curb the inflow of irregular migrants through the Mediterranean Sea. In 2018, the bloc allocated it 148 million euros to fund various programs to reinforce border control.

Notably, Morocco is the only African country to share a land border with the European Union, by virtue of the two small Spanish enclave cities of Ceuta and Melilla that are surrounded by Moroccan territory—making some level of cooperation with European officials all but essential. These borders have been the scene for violent interactions between border guards and sub-Saharan African migrants. In the latest of these incidents, in July 2022, approximately 2,000 people attempted to climb the barbed-wire fences separating Morocco and Melilla; at least 23 migrants died and hundreds went missing. Both Spanish and Morocco border guards were absolved of any wrongdoing related to the incident, although almost 300 migrants were later arrested and sentenced to prison for as long as three years.

EU migration funding demonstrates a commitment to supporting Morocco into becoming a country of settlement, with Morocco at times seeming to acknowledge its (reluctant) position as host to a growing number of sub-Saharan African migrants. Many of these migrants may have originally intended to reach Europe but settled for the long term in Morocco. In recent years, partly in response to international criticism, the country has given legal status to tens of thousands of immigrants. The 2014 National Strategy for Migration and Asylum set the stage for two large-scale regularization campaigns in 2014 and 2017, resulting in residency permits for approximately 50,000 irregular immigrants. Reforms continued through laws and regulations such as ministerial circular No. 13-487, which grants all sub-Saharan African children in Morocco unrestricted access to public education. Still, sub-Saharan Africans regularly face challenges in the country and Morocco is primarily a country of transit.

Pandemic and Intensified Hostility

As borders worldwide grew more rigid with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, travel bans and restrictions reduced mobility across Africa and towards the European Union, including through Algeria and Morocco. In Morocco, thousands of migrants were deported with little ceremony during the pandemic, due to the vast powers granted by emergency decree to the Ministry of Interior.

The recent intensification of the geopolitical conflict between Algeria and Morocco has also shaped the management of sub-Saharan migration. As tensions have heated up amid Rabat’s recognition of Israel and other developments, the countries have intensified border controls and sought to funnel migrants in each other’s direction. Meanwhile, thousands of migrants sought to cross from Morocco to Spain’s enclave cities in 2021 and 2022, amid a spiraling dispute between the countries over the status of Western Sahara; Spain eventually agreed to back Morocco’s plan to grant a form of autonomy to the territory.

Divergent Emigration Policies, Different Patterns

In earlier eras, the countries’ disparate approaches were more clearly on display with regards to emigration. After achieving independence, both nations confronted similar challenges over economic stagnation and political instability, which served as key push factors driving emigration. Both also sought to suppress Berber minority groups in favor of a pan-Arabist ideology. However, they acted in different manners; Algeria initially opted for a ban on emigration, which it later relaxed, while Morocco adopted a more complex set of measures to control and direct outflows in a way that benefitted the state and reduced the prospect of political dissent abroad. Partly these approaches were rooted in Cold War allegiances; Algeria sided with the Soviet Union, while Morocco aligned with the West. But they manifested in patterns of diasporas, emigration, and remittances that persist to this day.

Algeria

Before winning independence in 1962, Algeria was an integral part of France, not just a colony. While this worked mostly to Algeria’s disadvantage, for example facilitating the looting of its resources, this status also allowed Algerians to easily migrate to France and become citizens. Migrants tended to be single men who headed to cities such Marseilles and Paris, although they often faced hostility from French lobbies and unions that feared losing their influence to colonial workers. The number of registered Algerian workers in France jumped from 100,000 in 1924 to 300,000 in 1956.

Algerian migrants tended to be Kabyle Berbers, a minority ethnic group indigenous to the country’s mountainous north. Details of this migration are contested and connected to a larger debate about ethnicity, but Berbers, whose homelands were affected by adverse environmental conditions and who were often preferred by colonial recruiters, undeniably constituted a majority of Algerian migrants to France during this period. French officials tended to see Berbers as more work-oriented, less religious, and more aligned with French values than Arabs.

But Arab Algerian leaders feared Berbers might build wealth and political allegiances in the West to challenge the new regime, so in 1973, President Houari Boumédiène banned Algerian migration to France. Although the policy was ostensibly a reaction to racist attacks on Algerians, evidence suggests it emerged out of a desire to control the Algerian diaspora and limit the outflow of Berbers, who might join an increasingly vocal opposition in France. Although Berber migrants confronted pressure from French labor unions, migrants were able to respond with their own associations to lobby for their rights. Engagement in this democratic exercise added to the political experience migrants were gaining in France, presenting a significant concern for the populist Arab elite in post-independence Algeria.

Restrictions on emigration seem to have had a limited effect on curbing political opposition among diaspora members. France continues to be a stronghold of the self-determination Kabyle movement, with this reality at times a source of tension between the two countries. Meanwhile, the Algerian civil war (1991-2002) led to the displacement of approximately 1.5 million Algerians, both internally and towards Europe, particularly France. Algerian political opponents abroad have occasionally fomented unrest in their origin country.

Morocco

Following its independence in 1956, Morocco came to view emigration as a vehicle for foreign currency and a safety valve to release pressure over political instability and difficult economic conditions. Rather than allow the discontented to grow enchanted with opposition groups, the government—partly run by a monarchy with extensive powers—saw in them an opportunity to earn money abroad that could be sent back to invest in Morocco. Consequently, the government facilitated emigration, but controlled it to encourage outflows from particular regions such as the northern Rif and southern Sous, which were the most affected by poverty and drought, as well as the most inclined to protest.

To accomplish this goal, the government selectively issued passports primarily to individuals from these regions and those who had been vetted by military governors and influential public officials. By limiting passports mostly to single men with limited education or men who had been already vetted by local authorities, the government sought to limit the potential for dissent activities abroad.

The government also directed European recruiters to certain areas, namely the Rif and Sous. Most Moroccans migrating to Europe traveled under bilateral labor agreements in which the Moroccan government had large discretion regarding the choice of candidates. The Ministry of Labor was responsible for suggesting recruitment zones and did so based on the premise that political opposition thrived in poverty. Hence, by giving people a chance to work abroad, they would likely be less engaged in domestic politics.

The Moroccan state sought to closely monitor its nationals in Europe, using embassies, mosques, and civil-society groups created by Moroccans with close links to the government. Teachers and imams sent by the country to maintain children’s cultural heritage often collected information on Moroccans active in labor unions abroad. In addition, the migrant-focused offices known as Amicales, which were created by large companies in close contact with the state, consistently sought to prevent collective mobilization and discouraged the creation of independent nongovernmental organizations, including those demanding equal rights for Moroccans in Europe. This tactic was based on the logic that Moroccans' experiences with political activism abroad might be used to support leftist parties back home. The state’s repressive apparatus to maintain control on migrants—which extended to harassing and arresting activists who returned to Morocco and, at times, confiscating their passports—characterized the so-called Years of Lead, from the early 1960s until the early 1980s.

By the mid-1980s, the government no longer faced grave internal challenges and, with the fall of the Soviet Union, left-wing opposition faded, paving the way for a more relaxed approach. Emigrants were no longer viewed as threats to the state, but rather loyal subjects of the king. In 1984, King Hassan II announced that Moroccans abroad could participate in elections and would have representation within parliament. Later, he created the Hassan II Foundation for Moroccans Living Abroad (Fondation Hassan II pour les Marocains Résidant à l'Étranger) to assist returning Moroccans, as part of large-scale reforms and liberalization that accelerated with the ascendence of King Mohammed VI in 1999. The new king developed a national strategy for diaspora engagement and sought to address the impact of some repressive policies predating his reign.

Results of the Two Approaches

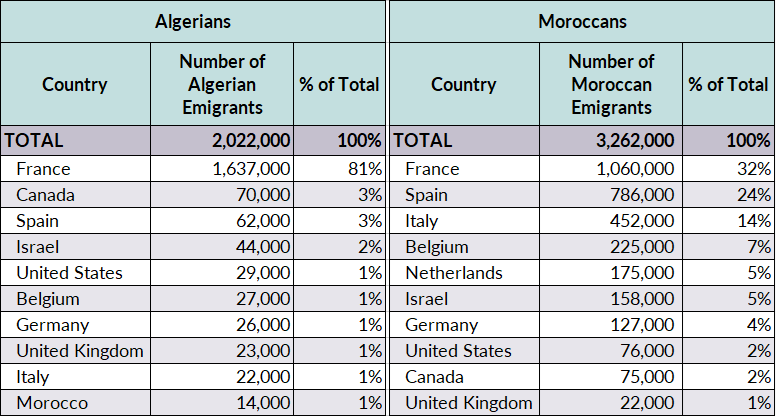

The results of these divergent strategies taken by Morocco and Algeria are partially reflected in current emigration patterns. Eighty-one percent of Algeria’s 2 million emigrants lived in France as of 2020, according to UN data, whereas Moroccan nationals are more evenly scattered across the European Union, with sizable numbers also in Spain (another European nation with long historical ties to Morocco), Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands. While there are certainly other factors at play, these histories help explain this distribution.

Table 1. Algerian and Moroccan Emigrants by Country of Destination, 2020

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Population Division, “International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin, Table 1: International Migrant Stock at Mid-Year by Sex and by Region, Country or Area of Destination and Origin,” accessed March 22, 2023, available online.

Perhaps surprisingly given bilateral tensions, Morocco is home to a sizable number of Algerian migrants. According to Morocco’s latest national census (from 2014), Algerians were the third largest migrant group in the country, representing 7 percent of all immigrants. On the Algerian side, the most recent available data from the National Employment Agency (from 2008) showed that 3 percent of work permits granted to foreign nationals went to Moroccans. This small number reflects Algiers’s repeated hostility towards Moroccans. As many as 350,000 Moroccans were expelled by Algerian authorities in 1975 following a flare-up in the Western Sahara dispute, and more recently, in March 2021, Moroccans living in a disputed border area had their property and land confiscated, among other abuses. These farmers owned and sowed the fields and had tended to palm trees for generations, yet found themselves on the wrong side of border divisions and subject to Algeria’s disinterest in cooperation with Morocco on border management issues.

These divergent histories are also reflected in remittance inflows. Morocco received U.S. $10.7 billion in remittances via formal channels in 2021, according to the World Bank, accounting for 7.5 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP). Algeria, in comparison, received less than U.S. $1.8 billion, representing 1.1 percent of its GDP. Algeria’s skepticism towards its diaspora has stifled its motivations to adopt a diaspora engagement policy, and its reliance on natural gas and oil exports provide an alternate source of foreign currency that Morocco lacks.

Figure 1. Annual Official Remittance Flows to Algeria and Morocco, 1990-2022*

* Data for 2022 are based on World Bank estimates

Source: World Bank Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD), “Remittance Inflows,” May 2022 update, available online.

Mixed Diaspora Focus

Since the 1990s, Morocco has prioritized its diaspora engagement policy and structures, as manifested in the creation of a Ministry in Charge of Moroccans Living Abroad and Migration Affairs (Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, de la Coopération Africaine, et des Marocains Résidant à l'Étranger), later subsumed into the Foreign Ministry. Through the ministry, the government seeks to connect emigrants and other members of the diaspora with the country through investment, access to education and affordable housing, and symbolic gestures such as Operation Marhaba, an annual government effort designed to assist returning emigrants and diaspora members looking to visit the homeland for short periods, usually during summer holidays. During Operation Marhaba, the government dispatches doctors, psychologists, and others to welcome centers throughout the country and at border points. In 2022, more than 3 million Moroccan diaspora members returned for a visit, many in connection with this event.

Algeria has only in recent years paid attention to its diaspora. In 2015, the government announced its Action Plan 2015-2020 to promote cultural contact with Algerians residing abroad, through programs such as summer universities. However, the major focus of Algeria’s diaspora policy is recruiting highly skilled Algerian emigrants, and data on the success of this rather nascent effort are lacking. Moreover, Algeria lacks a strong and independent institution focused solely on its diaspora.

Neighbors, Rivals, and Contrasts

Both Algeria and Morocco operate in a very dynamic geopolitical context, with continually emerging challenges. History shows that the two countries have tended to respond to these challenges differently; Morocco has demonstrated a tendency to balance security concerns with economic needs, while Algeria has consistently prioritized sovereignty issues and security over economic interests. This tendency continues to manifest itself in the way the states manage the inflow of sub-Saharan migrants.

Falling oil prices in 2018 caused significant social unrest in Algeria and motivated the state to target sub-Saharan African migrants through a series of large-scale deportation campaigns affecting almost 25,000 migrants. Recently, rising oil prices amid the war in Ukraine have granted Algeria’s leaders space for political maneuvering and reduced the need to scapegoat migrants. However, the conflict’s impact on food security across Africa will represent an additional push factor for migration towards Europe, increasing pressure on North Africa.

Algeria’s present management of sub-Saharan migration demonstrates its unwavering concern with security. Its competition with Morocco for continental influence might seem to push it to welcome African migrants to win favor from other African leaders, much as Morocco did in 2014. However, Algiers has continued large-scale arrests and deportations of African migrants.

On the other hand, Morocco’s approach is best manifested in its attempt to balance its commitments to the European Union to curb the inflow of sub-Saharan migrants with its desire to avoid becoming their final destination. Despite the government’s efforts to project the country as a welcoming destination for sub-Saharan Africans, EU-supported efforts to promote settlement and integration in Morocco, and the progress achieved since 2014, an increasing body of evidence shows Morocco is shifting its approach and regressing to securitization. The focus seems to have shifted to meeting three objectives: limit migrants’ presence in coastal cities from where they might head to Europe, create so-called welcome centers and other tools to contain migrants in the south of the country, and limit mobility through the territory by restricting the use of public transportation.

Algeria and Morocco play important roles at the nexus of Africa and Europe, and this central position has defined their migration histories as much as their bilateral rivalry. Recent escalations of tensions suggest that their competition will remain heated in the coming years.

Sources

Al Jazeera News. 2021. Algeria Closes Airspace to All Moroccan Planes. Al Jazeera News, September 22, 2021. Available online.

Arrouche, Kheira. 2022. Migration Governance in Algeria: Challenges, Interests and Future Prospects. Barcelona: European Institute of the Mediterranean. Available online.

Boumghar, Lotfi. N.d. The Algerian Position on the European Neighbourhood Policy. IEMed Mediterranean Yearbook 2013. Accessed May 4, 2023. Available online.

Cohen, Muriel. 2017. Post-Colonial Algerian Immigration: Putting Down Roots in the Face of Exclusion. Le Mouvement Social 258 (1): 29-48. Available online.

Collyer, Michael. 2012. Moving Targets: Algerian State Responses to the Challenge of International Migration. Revue Tiers Monde (2): 107-22. Available online.

---. 2012. The Changing Status of Maghrebi Emigrants: The Rise of the Diaspora. Middle East Institute, May 4, 2012. Available online.

de Haas, Hein. 2007. Between Courting and Controlling: The Moroccan State and ‘Its’ Emigrants. Centre on Migration, Policy and Society working paper No. 54. Available online.

Drhimeur, Lalla Amina. 2020. Moroccan Diaspora Politics Since the 1960s: Literature Review. Istanbul: İstanbul Bilgi University. Available online.

El Ghazouani, Driss. 2019. A Growing Destination for Sub-Saharan Africans, Morocco Wrestles with Immigrant Integration. Migration Information Source, July 2, 2019. Available online.

Hammoudi, Leïla. 2021. Moroccans in Algeria Fear for the Future after Diplomatic Ties Severed. Middle East Eye, August 29, 2021. Available online.

Harris, Jonathan. 2018. Between Nativism and Indigeneity in the Kabyle Diaspora of France. Europe Now, February 1, 2018. Available online.

House, Jim. N.d. The Colonial and Post-Colonial Dimensions of Algerian Migration to France. Institute of Historical Research. Accessed March 22, 2023. Available online.

Kasraoui, Safaa. 2019. Video Shows Testimonies of Moroccans Expelled from Algeria in 1975. Morocco World News, December 26, 2019. Available online.

Migration Policy Centre. 2013. Algeria: Migration Profile. Florence: Migration Policy Centre. Available online.

Ouhemmou, Mohammed. 2018. Moroccan Migration Policy: Education as a Tool to Promote the Integration of Sub-Saharan Migrants. In Morocco's Socio-Economic Challenges: Employment, Education, and Migration – Policy Briefs from the Region and Europe, eds. Dina Fakoussa and Laura Lale Kabis-Kechrid. Berlin: German Council on Foriegn Relations. Available online.

---. 2021. Migration and Border Conflicts in Africa: A Comparative Analysis of the Moroccan and Algerian Migration Policies. In Intra-African Migrations: Reimaging Borders and Migration Management, eds. Inocent Moyo, Jussi P. Laine, and Christopher Changwe Nshimbi. London: Routledge.

Statewatch. 2019. Aid, Border Security and EU-Morocco Cooperation on Migration Control. London: Statewatch. Available online.