You are here

Border Challenges Dominate, But Biden’s First 100 Days Mark Notable Under-the-Radar Immigration Accomplishments

President Joe Biden speaks to journalists at the White House. (Photo: Adam Schultz/White House)

President Joe Biden entered office with an ambitious immigration agenda, yet has seen some of his administration’s early actions overshadowed—and tempered even—amid significant public attention over the high numbers of asylum seekers and other migrants arriving at the U.S. southern border. More migrants were encountered at the border in March than any month since 2001, and the government has been slow to scale up its capacity to address the increasing numbers, while also giving mixed messages about who will be allowed into the country.

Yet as Biden nears 100 days in office on April 30, he has, with little fanfare, notched accomplishments in other areas of immigration policy that rival and in some cases surpass what his predecessors did in the same amount of time. As of this writing, the Biden administration had taken 94 executive actions on immigration, according to a Migration Policy Institute (MPI) count. This compares with the fewer than 30 taken during the first 100 days of Donald Trump’s presidency, which was arguably more active on immigration than any prior U.S. administration.

The early Biden actions have, among other things, narrowed the scope of immigration enforcement in the U.S. interior, terminated most travel and visa restrictions imposed during the prior administration, extended humanitarian protections, made immigration benefits more accessible, and adopted something of a new approach to border enforcement. Biden also notably pledged his support for sweeping immigration legislation that includes legalization for the nation’s estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants.

The president’s actions can be divided into two categories: those undoing Trump actions and those aimed at enacting his own new policies to make the immigration system more welcoming. Of the Biden presidency’s 94 executive actions on immigration so far, 52 have set the stage for undoing Trump administration measures, MPI found.

Biden’s actions have in some ways gone beyond what he promised to do in his first 100 days, and in other ways fallen short. On the campaign trail he promised 26 discrete immigration actions during his first 100 days, according to MPI’s count. But the administration has achieved just 12 of these, leaving unfinished the task of chipping away at restrictions on asylum, among other measures. His administration has received some sharp criticism from backers in the immigrant-rights and refugee advocacy movements. This backlash was especially pointed when Biden backtracked from a February commitment to more than quadruple the ceiling for refugees admitted before October; within the span of a day, the administration reversed course and has since reaffirmed it will increase the limit, albeit not necessarily the 62,500 earlier pledged.

This article examines the Biden administration’s actions on immigration over its first 100 days; its shortcomings, which have mainly been at the border; and the prognosis for movement on as-yet-unfulfilled promises.

Biden’s Actions Away from the Southern Border

While much attention has focused on the challenges at the U.S.-Mexico border, the administration’s first 100 days may ultimately prove more consequential at a policy level when viewed in terms of the wide array of policy changes that affect immigration enforcement in the U.S. interior and at the border, foreigners’ ability to travel to the United States, and immigrants’ ability to access various benefits including legal status.

Interior Enforcement

Arguably the administration’s quickest and most dramatic accomplishment was changing immigration enforcement in the U.S. interior, narrowing enforcement much faster than Trump broadened it upon taking office in 2017. On Inauguration Day, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued new, temporary enforcement priorities, which were further fine-tuned and operationalized on February 18. These priorities limited U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers to targeting removable noncitizens who are national security risks; who entered the United States on or after November 1, 2020, either illegally or legally and have since fallen into unlawful status; and who are public safety threats with certain criminal convictions or gang involvement. Removable noncitizens falling outside these priorities can be arrested, detained, or removed only with an ICE supervisor’s approval. These changed prosecutorial discretion guidelines were the inverse of DHS changes enacted by the Trump administration in February 2017, when it quickly broadened enforcement priorities to include all unauthorized immigrants. President Barack Obama’s administration did not establish enforcement priorities until 2010, a year and a half into his administration.

The results of the new enforcement priorities under Biden have been quick to manifest. ICE arrests have decreased by more than 60 percent, from an average of 6,800 monthly arrests in the last three full months of the Trump administration to 2,500 in February, Biden’s first full month in office. For comparison, by Trump’s first full month in office, ICE arrests increased by 26 percent over the average of the last three full months of the Obama administration.

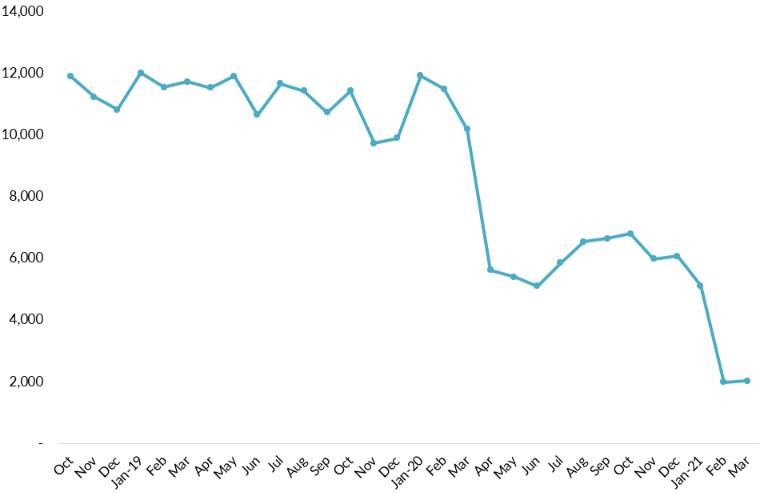

Detention of noncitizens arrested by ICE likewise decreased by more than two-thirds in the first 100 days of the Biden administration, from an average of nearly 6,300 monthly book-ins from October to December to an average of 2,000 in February and March (see Figure 1). Compared to February 2020, just before ICE limited enforcement due to the COVID-19 pandemic, monthly detentions decreased by 82 percent.

Figure 1. ICE Detention Book-Ins Originating from ICE Arrests, October 2019-March 2021

Source: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), “Detention Management Statistics—FY 2019 Detention Statistics,” accessed April 10, 2021, available online; ICE, “Detention Management Statistics—FY 2020 Detention Statistics,” accessed April 10, 2021, available online; ICE, “Detention Management Statistics—Detention FY 2021 YTD, Alternatives to Detention FY 2021 YTD and Facilities FY 2021 YTD, Footnotes,” accessed April 10, 2021, available online.

In addition to reducing the overall number of individuals arrested and detained by ICE, the Biden administration has started to end long-term detention of families. Advocates have been pushing to end this practice since the first family immigration detention facility opened in Leesport, Pennsylvania in 2001. During the Obama administration and the first year of the Trump administration (the only year of the administration for which data are available), an average of 70 people were held there each day. By February 26, all families held in that facility had been released.

However, hundreds of families (more than 900 people as of mid-March) continue to be detained for shorter periods in the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, which is one of two family detention facilities in Texas. This is similar to the average number of individuals detained there during the last two years of the Obama administration and the first year of the Trump administration. There is no publicly available information about the number of people detained at the other Texas facility, the Karnes County Residential Center. The Biden administration has stated that it intends to turn both facilities into processing centers where families will be held for fewer than 72 hours and then released, though that transition has not yet been completed. As of March, ICE was releasing families from these facilities within ten to 15 days.

Under Biden, ICE also restarted a process allowing review of arrests, detentions, and intended removal of noncitizens who are outside its enforcement priorities. Under the revised system, requests for such reviews can be elevated to ICE headquarters, if necessary. A similar review process existed during the latter part of the Obama administration but was shut down during the Trump years.

With these changes, Biden’s administration has indicated that ICE will once again exercise prosecutorial discretion nationwide and target only the highest priority cases. While arrest and detention numbers may increase gradually as pandemic limitations loosen, the administration has successfully implemented its tailored enforcement priorities. This change has a real on-the-ground effect on who is subject to arrest, detention, and removal.

Travel and Visa Restrictions

Biden has ended several bans on travel and visa issuance implemented over the course of the prior administration. On his first day in office Biden terminated the travel bans that prevented nationals from 13 predominantly Muslim and African countries from receiving visas. Under a new State Department process, nearly 41,900 people who were denied visas under the bans and were not issued waivers are now eligible to reapply. However, most people (all but approximately 800, who were denied on or after January 20, 2020) must resubmit their applications and pay hundreds of dollars in new fees.

On February 24, Biden terminated his predecessor’s April 2020 ban on all immigrant visa issuance except those for spouses and minor children of U.S. citizens and certain immigrant investors. Separately, he allowed a similar ban prohibiting new visas for temporary workers and exchange visitors to expire at the end of March. Trump justified both bans on the grounds that these immigrants would compete against unemployed U.S. workers in an economy that was already in freefall—the first time the United States used such an argument to suspend entries of qualified immigrants.

Lifting the ban on immigrant visa issuances is likely to have a greater effect than the expiration of the prohibition on temporary workers and other visitors. The number of immigrant visas in the banned categories issued as exceptions during the period the ban was in effect decreased by 94 percent compared to visas in those categories during the same period a year prior. This drop is unlikely to be explained by global travel slowdowns during the pandemic; issuances of immigrant visas in categories not subject to the ban also decreased while the ban was in effect, largely due to consular closures, but only by 45 percent, suggesting that the ban prevented many immigrants from making trips that would have happened otherwise. The end of the nonimmigrant visa ban will likely have less of an effect, since issuances of such visas decreased by similar percentages in both banned and exempt categories.

Humanitarian Protection

During its first 100 days, the Biden administration took major steps to protect certain national groups already in the United States from deportation. The most significant was its March designation that Venezuelans were eligible for Temporary Protected Status (TPS), making an estimated 323,000 Venezuelans in the United States eligible for work authorization and protecting them from deportation for at least 18 months. It also designated Myanmar (also known as Burma) for TPS, with an estimated 1,600 Burmese eligible for protection. If all eligible Venezuelans and Burmese were to be granted TPS, the overall number of TPS holders would more than double from the current 319,000.

Trump attempted to terminate TPS for 97 percent of recipients, but legal challenges blocked those terminations. At the end of his administration, Trump designated Venezuelans for Deferred Enforced Departure (DED); TPS offers a more stable status given it is more difficult to revoke.

The Biden administration also has begun to restart the Central American Minors (CAM) program, terminated in 2017 by Trump, which allows Central American children who have a parent lawfully present in the United States to be granted refugee status or be paroled into the country. The 2,700 children approved to travel prior to CAM’s termination will be the first group eligible to come to the country. The program will then be expanded to new applicants.

Immigration Benefits

Steadily, the new administration has started undoing Trump policies making it more difficult for immigrants to come to or stay in the United States. The most significant of these was the public-charge rule, which subjected green-card applicants and people renewing temporary visas to a forward-looking test to assess whether they would be likely to use public benefits in the future. The rule, issued in August 2019 but in effect intermittently due to court interventions, affected lower-income immigrants and their families. Not only did it result in many more individuals being denied visas on public-charge grounds—nearly 21,000 in fiscal year (FY) 2019 compared to 1,000 in FY 2016—but also had a chilling effect, prompting some immigrants to preemptively withdraw their families from benefits programs out of fear of damaging their immigration cases.

Biden’s administration reversed the public-charge rule in two moves. First, on March 9, it stopped defending it in legal challenges, thus allowing an earlier court order vacating the rule to go into effect nationwide. In practice, this restored the much narrower 1999 guidance for determining whether would-be immigrants are inadmissible on public-charge grounds. Second, DHS then codified this reversion to the earlier guidance without going through a formal notice-and-comment period of rulemaking, arguing that immediate action was necessary to meet the court order. This strategy of deferring to court rulings likely makes the change much less vulnerable to legal challenge than it would have been if the administration had issued a new regulation through the traditional process.

The administration has also rescinded a smattering of other Trump administration policies. Among the most notable: Shelving a new citizenship civics test that was both more time-consuming and more difficult. The administration also has revoked a DHS memo encouraging heightened enforcement against immigrants whose benefits applications were denied. While Biden has not announced a forward-looking immigration-benefits agenda, his administration has successfully terminated some policies restricting access to such benefits.

Border Policy and Root Causes of Migration

The large numbers of migrants arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border have grabbed headlines, and the administration has fallen short in some of its responses, as will be discussed below. Still, Biden did take some notable early steps, most importantly exempting unaccompanied children from the public-health order allowing authorities to immediately expel arriving migrants without providing access to asylum. Children now are being allowed into the country to seek relief in immigration courts, as they were allowed to do prior to March 2020.

The administration also ended the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), also known as the Remain in Mexico program. On February 19, asylum seekers waiting in Mexico with active U.S. court cases began to be admitted into the United States to complete their court proceedings. Approaching Biden’s 100th day in office, MPP enrollee processing was taking place at six ports of entry; 7,200 out of an estimated 25,000 enrollees with active cases had been admitted as of April 15. Migrants undergo COVID-19 testing prior to entering the United States.

The White House has also started to focus attention on addressing root causes of migration in Central America, with Vice President Kamala Harris charged to shepherd an administration-wide effort to address conditions in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) sent a team to the region in April to scale up emergency humanitarian assistance in light of the pandemic, aftereffects of hurricanes that struck in late 2020, and other challenges. Thus far, work with these countries has focused on short-term measures to reduce the pace of migrants’ arrival at the U.S. border. But the administration has consistently noted that long-term efforts to address poor governance and create economic opportunities in Central America will be key to stem irregular migration.

Where Biden Has Hit Turbulence: The Border

The administration has confronted major challenges formulating a consistent policy and appropriate message to deal with the arrival of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border. March 2021 saw the highest number of interceptions of unauthorized migrants at the border since March 2001. This included the highest ever numbers of unaccompanied children (nearly 19,000), the third-largest ever number of people traveling as families (nearly 53,000), and the highest number of single adults (nearly 97,000) since at least 2013.

These numbers on their own might not have morphed into a crisis had there been an adequate system to screen and adjudicate migrants’ eligibility for protections, paired with sufficient capacity to shelter all the arriving children. However, the Biden administration, like the Trump and Obama administrations before it, was not prepared. It has been slow to expand temporary capacity to shelter unaccompanied children, standing up emergency facilities only in mid-March. And it has not attempted to restructure the asylum system to ensure protections for those found to merit asylum, particularly families, and remove those who fail to qualify. Administration officials have hinted that a forthcoming policy change may address these issues.

In addition to a delayed policy response, the administration’s messaging has led to confusion. For example, officials have repeatedly claimed the border is closed to arrivals and that authorities will expel families who cross the border. However, only 33 percent of arriving families were expelled in March. It is not clear how authorities decide whether to expel a family. As one Tijuana shelter director told the San Diego Union-Tribune, “This isn’t a policy—it’s a game of chance.”

As long as getting into the United States is seen as a dice roll with notably favorable odds, rather than governed by a uniform and consistently applied policy, illegal crossings by families will likely persist. Smugglers have been eager to tout successful entries as an example for others aspiring to reach the country. Confusing messaging from the White House may be no match for a smuggler’s promise.

Still-Pending Actions on Refugees, Asylum Seekers, Enforcement, and Legalization

Biden has taken preliminary steps towards fulfilling additional campaign promises on immigration. Increasing the ceiling on refugee admissions and speeding resettlement up for the remainder of the current fiscal year, which runs through September, would be one promise that would affect a large number of people and would raise U.S. global standing. In February the president told Congress he would raise the FY 2021 limit set by Trump from the record-low 15,000 level to 62,500. However, the administration backtracked on April 16, announcing it would keep in place the 15,000 ceiling. Following quick backlash from Democratic lawmakers and advocates, it yet again reversed its decision and expressed intent to raise the number to some unstated level by May 15.

Regardless of the ceiling, the resettlement pace has been conspicuously slow. Fewer than 2,100 refugees were resettled during the first six months of FY 2021, well under the 15,000 limit. In fact, the rate of monthly admissions has slightly decreased, from a monthly average of 333 refugees from October to December, under Trump, to an average of 324 in February and March, under Biden.

The president has also ordered a review of some of the “extreme vetting” measures imposed on visa applicants and refugees by the Trump administration, but most remain in effect. These measures include requiring some applicants to provide address and employment history stretching back 15 years and social media accounts going back five years, and requiring lengthier security checks for broader populations of refugees than in previous administrations. Enhanced security measures were not an invention of the Trump administration; some requirements, such as additional security checks for certain nationalities and individuals with potential terrorism ties, have been in place for decades. Even with bans on travel and visa issuance lifted, the process of traveling to the United States remains complex.

Two important actions on asylum may also be forthcoming, both of which would fulfill Biden campaign promises. Combined, they would perhaps impact more people than any other reforms the administration made to the asylum system.

The first is eliminating the transit-country asylum ban, a Trump rule denying asylum to migrants who traveled through a country other than their own before crossing the U.S.-Mexico border, making ineligible any Central American asylum seeker transiting Mexico. A federal court blocked multiple versions of the rule and government attorneys under Biden have indicated that it may be modified or rescinded in the near future, based on an ongoing policy review.

Additionally, a relatively easy but far-reaching action is for Attorney General Merrick Garland to issue a new precedential decision allowing victims of domestic and gang violence to again qualify for asylum. Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions made it largely impossible for asylum seekers to qualify on these grounds, often invoked by Central Americans.

Biden also promised on the campaign trail to eliminate private criminal and immigration detention. While he signed an executive order directing the Justice Department not to renew contracts with private prison companies, he has not given a similar order to DHS for immigrant detainees. For-profit facilities offer poor living conditions for immigrant detainees, although it is worth noting that inspector general investigations have also found dangerous, dilapidated, and overly restrictive conditions in public facilities, such as those operated by local governments. However, advocates argue there is much less oversight, standardization, and accountability for private prisons.

The Biden administration may be slow to phase out private immigration detention facilities because there is much higher reliance on these centers than in the criminal detention system. As of 2016, three-quarters of all immigrant detainees were held in facilities operated by private prison contractors; in contrast, only 16 percent of federal prisoners were housed in private prisons at the end of 2019. It thus may be more challenging for the federal government to replace for-profit immigration detention.

Additionally, Biden’s Inauguration Day orders included a halt on new border wall construction, but he has yet to decide how to spend funds Congress already appropriated for the wall. Multiple agencies are evaluating whether to spend the money completing various wall sections, use it for associated technology and roads, or request that Congress take it back;, no decision has been announced. There was about $3.3 billion in unused border wall funds as of January 21, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers estimates. It is unclear how much of that was appropriated by Congress versus being redirected for the wall by the Trump administration from military and other accounts. In its FY 2022 budget proposal, the White House has asked Congress to rescind any wall funds unused at the end of FY 2021.

What Role for Congress?

While Biden can implement many changes through executive action, he faces an uphill battle where congressional action is needed. The U.S. Citizenship Act, introduced by Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ) and Rep. Linda Sánchez (D-CA), includes the president’s pledge to create a pathway to citizenship for the country’s 11 million unauthorized immigrants. It also features Biden’s proposed legal immigration system changes, for example exempting visas for spouses and children of green-card holders from numeric caps and allowing people with approved family-based petitions to enter the country before a green card is available.

Biden and congressional Democrats have all but concluded that legislative action on such a large package is impossible in the near term. They instead intend to focus on smaller-bore efforts to legalize specific segments of the unauthorized population. These smaller bills are by no means guaranteed passage either. For instance, two House-passed bills have a tough, if not impossible, path to the 60 votes needed to end a likely filibuster in the Senate. One would offer a path to citizenship to TPS holders and DREAMers brought to the country as children, and another would do the same for farmworkers. It is not even clear that all Senate Democrats would support the measures if included in a new budget reconciliation bill, which needs only a simple majority to pass.

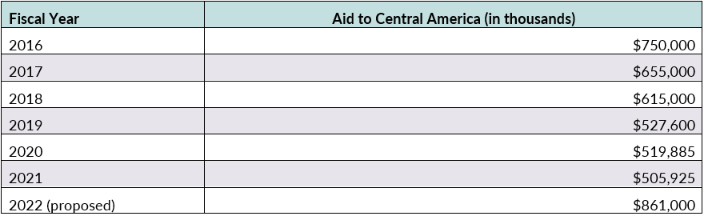

Passage of FY 2022 appropriations, on the other hand, is necessary for the government to continue operation. In his budget request, Biden has proposed that Congress appropriate $861 million for assistance to Central American countries as a downpayment on his promise to send $4 billion in aid over four years.

Table 1. Federal Appropriations for Assistance to Central America, FY 2016-22

Sources: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulation of explanatory statements from annual appropriations acts for the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, fiscal year (FY) 2016-21, accessed April 15, 2021, available online; U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Executive Office of the President, “Summary of the President’s Discretionary Funding Request” (OMB, Washington, DC, April 2021), available online.

On the whole, Biden’s first 100 days demonstrate the power that the president has to shift the course of U.S. immigration policy. This executive power was first embraced by Obama and taken to an unprecedented level by Trump. Unlike his predecessor’s first 100 days, though, Biden’s have been relatively unmarred by legal challenges. As the Senate continues to confirm Biden’s appointees to major immigration agencies and they gain footing, it is likely that his administration’s executive actions on immigration will continue to grow.

Sources

Bernstein, Hamutal, Dulce Gonzalez, Michael Karpman, and Stephen Zuckerman. 2019. With Public Charge Rule Looming, One in Seven Adults in Immigrant Families Reported Avoiding Public Benefit Programs in 2018. Blog post, Urban Institute, May 21, 2019. Available online.

Capps, Randy, Muzaffar Chishti, Julia Gelatt, Jessica Bolter, and Ariel G. Ruiz Soto. 2018. Revving Up the Deportation Machinery: Enforcement and Pushback under Trump. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

Carlisle, Madeleine. 2021. ‘Much More Work to Be Done.’ Advocates Call for More Action Against Private Prisons After Biden's ‘First Step’ Executive Order. Time, January 29, 2021. Available online.

Congressional Research Service. N.d. Appropriations Status Tables. Accessed April 15, 2021. Available online.

Dawsey, Josh and Nick Miroff. 2020. Biden Order to Halt Border Wall Project Would Save U.S. $2.6 Billion, Pentagon Estimates Show. Washington Post, December 16, 2020. Available online.

Jenny Lisette Flores et al v. Merrick Garland et al. 2021. No. 85-4544-DMG. U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, Joint Status Report, March 26, 2021. Available online.

Jenny Lisette Flores et al v. Monty Wilkinson et al. 2021. No. CV 85-4544-DMG. U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, March 2021 Interim Report of Juvenile Coordinator Deane Dougherty Submitted by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, March 5, 2021. Available online.

Luan, Livia. 2018. Profiting from Enforcement: The Role of Private Prisons in U.S. Immigration Detention. Migration Information Source, May 2, 2018. Available online.

Miroff, Nick and Maria Sacchetti. 2021. Immigration Arrests Have Fallen Sharply Under Biden, ICE Data Show. Washington Post, March 9, 2021. Available online.

Morrissey, Kate. 2021. Biden Expelling Asylum-Seeking Families with Young Children to Tijuana After Flights from Texas. San Diego Union-Tribune, April 9, 2021. Available online.

National Immigrant Justice Center. N.d. ICE Detention Facilities as of November 2017. Accessed April 15, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Interactive Timeline: The Resurgence of Family Detention. Accessed April 15, 2021. Available online.

Pierce, Sarah and Jessica Bolter. 2020. Dismantling and Reconstructing the U.S. Immigration System: A Catalog of Changes under the Trump Presidency. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

Refugee Processing Center. N.d. Admissions and Arrivals—Refugee Admissions Report. Accessed April 11, 2021. Available online.

S.A. et al v. Donald J. Trump et al. 2020. No. 18-CV-03539 LB. U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, Defendants’ Seventh Quarterly Report, December 30, 2020. Available online.

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). 2021. USAID Deploys Disaster Assistance Response Team to Address Rising Humanitarian Needs in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. Press release, April 6, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2021. Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds; Implementation of Vacatur. Federal Register 86 (48), March 15, 2021: 14221-29. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2021. DHS Secretary Statement on the 2019 Public Charge Rule. Press release, March 9, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of State. 2021. The Department’s 45-Day Review Following the Revocation of Proclamations 9645 and 9983. Press release, March 8, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Implementation of Presidential Proclamation (P.P.) 9645. Accessed April 10, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Implementation of Presidential Proclamations (P.P.) 9645 and 9983: December 8, 2017 to January 20, 2021. Accessed April 10, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Table XX: Immigrant and Nonimmigrant Visa Ineligibilities (by Grounds for Refusal Under the Immigration and Nationality Act) Fiscal Year 2016. Accessed April 15, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Table XX: Immigrant and Nonimmigrant Visa Ineligibilities (by Grounds for Refusal Under the Immigration and Nationality Act) Fiscal Year 2019. Accessed April 15, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Departments of State, Homeland Security, and Health and Human Services. N.d. Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2021: Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Departments of State, Homeland Security, and Health and Human Services. Accessed April 10, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). 2021. Contact ICE About an Immigration/Detention Case. Updated March 24, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Detention Management Statistics—FY 2019 Detention Statistics. Accessed April 10, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Detention Management Statistics—FY 2020 Detention Statistics. Accessed April 10, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Detention Management Statistics—Detention FY 2021 YTD, Alternatives to Detention FY 2021 YTD and Facilities FY 2021 YTD, Footnotes. Accessed April 10, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Executive Office of the President. 2021. Summary of the President’s Discretionary Funding Request. Washington, DC: OMB, April 2021. Available online.

Wasem, Ruth Ellen. 2015. Immigration: Visa Security Policies. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.