You are here

Biden at the One-Year Mark: A Greater Change in Direction on Immigration Than Is Recognized

President Joe Biden delivers remarks in front of the White House. (Photo: Katie Ricks/White House)

While Donald Trump’s presidency is perceived as being the most active on immigration, touching nearly every aspect of the U.S. immigration system, President Joe Biden’s administration has far outpaced his predecessor in the number of executive actions taken during his first year in office. Yet the Biden administration’s pace of change has largely gone unnoticed, with immigrant-rights activists accusing it of going too slowly to unravel Trump actions and conservatives harshly critical of what they see as inattention to rising flows at the U.S.-Mexico border.

The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) logged 296 executive actions on immigration taken by the administration as of January 19—one day before Biden’s first anniversary in office. By contrast, the Trump administration carried out 86 executive actions during its first year and 472 over its four-year term, MPI analysts have found.

Given this pace of activity, why does the perception exist that the Biden administration has done little on immigration? This is largely because the media, political pundits, and activists have focused on the lack of progress on two of the president’s key campaign promises: legalization for the country’s unauthorized immigrant population and rebuilding an asylum system at the U.S.-Mexico border that was largely dismantled during the prior administration.

True to his campaign narrative, Biden, on his first day in office, issued six executive orders on immigration and sent Congress a framework for a comprehensive immigration reform bill, the most ambitious of any president in a generation. It was a signal, both to establish a sharp contrast from the Trump era, known for its signature anti-immigration stance, and to declare immigration a high priority for the president. Expectations were thus set high. But the administration has struggled to tackle the record-breaking arrivals at the U.S. southern border, drawing disquiet across the political spectrum. And with the door to congressional action on immigration nearly closed, the Democrats’ base is restive.

Yet while most attention has focused on these unmet expectations, there can be no doubt that through large and small-bore executive actions alike the administration has advanced or changed policies in ways that have significant impact on humanitarian protection, immigration enforcement, and legal immigration, touching the lives of large numbers of immigrants. These actions cut a wide spectrum—from greatly narrowing the number of unauthorized immigrants vulnerable to arrest, detention, and removal; lifting some barriers to U.S. entry and to accessing immigration benefits; and in the humanitarian protection realm, extending eligibility for temporary protection to an additional 430,000 immigrants, raising the refugee resettlement ceiling to 125,000, and proposing a restructuring of the asylum system at the southwest border.

Nevertheless, many Trump-era policies remain in effect, particularly the more technical ones: 89 of the Biden administration’s 296 immigration executive actions to date have undone or started to undo Trump administration actions, leaving many more in place. This could be for a range of reasons, including that the Biden administration is not prioritizing their reversal, has concluded their reversal would be difficult, is facing bureaucratic resistance, or, in some cases, supports them.

This article reviews the major actions the Biden administration has taken during its first year in four areas: interior enforcement, humanitarian protection, legal immigration, and border enforcement. It does not aim to provide a comprehensive list of actions, but rather to summarize thematically the administration’s more prominent policy changes and their impact.

Interior Enforcement

The Biden administration’s changes to policies governing interior enforcement—arrests, detentions, and removals inside the United States—have been some of its most sweeping and impactful and yet among the least noted. Within two weeks of taking office, the administration issued new interim immigration enforcement guidelines, instructing U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers to limit enforcement to those who pose a national security risk, have been convicted of certain crimes, or who recently entered the country illegally. This was a sharp contrast to the Trump administration’s policy, under which virtually all estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants were considered a priority for removal. In late November, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas issued final enforcement guidelines. These guidelines set out the same priority groups, but, in a departure from a categorical enforcement approach, added some flexibility by instructing ICE officials to make individualized enforcement decisions based on the totality of circumstances and taking into consideration “aggravating” and “mitigating” factors in each case. This approach is conceptually different from the enforcement priorities issued by any prior administration by focusing on the person and not on the crime. This change, for example, could ensure that noncitizens with decades-old criminal convictions are not prioritized for deportation.

Beyond the recalibration of ICE enforcement, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in the last year has set out guidelines limiting immigration enforcement against specific populations, in specific locations, and in specific situations. ICE officers have been instructed generally not to arrest or detain pregnant, postpartum, or nursing individuals—though they can still initiate removal proceedings—and not to take enforcement actions against noncitizens who are applying for immigration benefits based on their status as crime victims. DHS also has restricted ICE arrests at or near courthouses. Finally, the department has expanded what was previously known as ICE’s sensitive locations policy, which since 2011 had prohibited enforcement in most cases at schools, hospitals, religious institutions, public ceremonies such as funerals or weddings, and protest sites. The new policy bars enforcement, with limited exceptions, at or near all medical or mental health-care facilities, places where children gather such as playgrounds and school bus stops, social services establishments, and disaster relief and emergency response sites. In an unprecedented move, Mayorkas also instructed the DHS immigration agencies (which beyond ICE include U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services [USCIS] and U.S. Customs and Border Enforcement [CBP]) to ensure that deported noncitizens who served in the U.S. armed forces can return to the United States if the agencies determine they were “unjustly removed.”

The administration has ended a controversial approach to enforcement: mass worksite operations. Such “raids” of businesses resulted in nearly 30,000 administrative arrests of unauthorized immigrants between fiscal years (FY) 2000 and 2020. In addition to halting this practice, Mayorkas, in another first, has incentivized unauthorized immigrants to report exploitative employment practices, by directing DHS agencies to consider offering legal protections such as deferred action to those who come forward.

Finally, the Biden administration ended long-term family detention, in use since 2001, repurposing all three family detention centers to hold single adults. It also closed two notorious adult detention centers: the Irwin County Detention Center in Georgia, which had been found to violate ICE detention standards and faced allegations by women detainees of medical abuse, and the C. Carlos Carreiro Immigration Detention Center in Massachusetts, where officials were determined to have violated detainees’ civil rights when they responded violently to a peaceful demonstration.

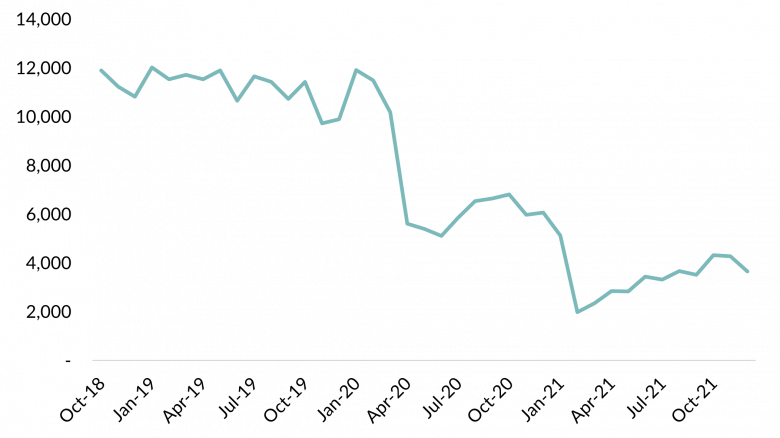

These combined interior enforcement actions have had perceptible effects. For one, the number of ICE arrests has dropped. In the last 11 months of the Trump administration, 6,000 noncitizens were booked into detention per month on average as a result of ICE arrests; that number dropped to 3,000 during the first 11 months of the Biden administration.

Figure 1. Initial Book-Ins to Detention Resulting from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Arrests, October 2018-December 2021

Note: Data for September 2021 are estimated based on a count of 1,291 initial book-ins to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody resulting from ICE arrests as of September 11, 2021.

Source: ICE, “Detention Management—Detention Statistics,” multiple years, updated January 10, 2022, available online.

Further, the overall average daily detained population fell to about 19,200 in FY 2021, the lowest level since FY 1999. This decline, despite the high level of detentions at the border, can be attributed to the precipitous drop of detentions of noncitizens arrested in the U.S. interior. In Biden’s first 11 months in office, the average daily population in detention as a result of ICE arrests was 5,300—a sharp drop from the 13,700 during Trump’s last 11 months in office.

Figure 2. Average Daily Population in ICE Detention, FY 1994-2021

Note: Data for fiscal years (FY) 1994-2002 measure average daily population in detention by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), which in 2003 was abolished and its duties subsumed into the new Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Sources: Alison Siskin, Immigration-Related Detention: Current Legislative Issues (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2004), available online; DHS, Congressional Budget Justification: FY 2016 (budget document, Washington, DC, DHS, n.d.), available online; DHS, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement: Budget Overview (budget document, Washington, DC, DHS, n.d.), available online; ICE, “Detention Management—Detention Statistics.”

Humanitarian Protection

While the Trump administration imposed severe constraints to humanitarian protection, the Biden administration has expanded the categories and number of individuals already in the United States or seeking entry who are eligible for legal protections such as deferred action, parole, Temporary Protected Status (TPS), asylum, or refugee status.

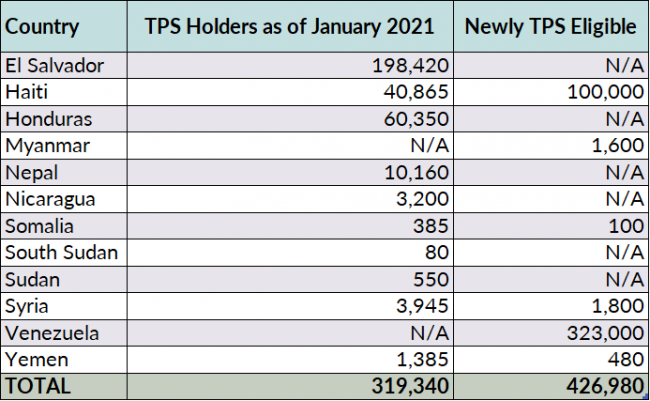

Whereas the Trump administration had attempted to terminate Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for most recipients, and was only blocked from doing so by the courts, the Biden administration newly designated nationals of two countries: Myanmar and Venezuela. TPS grants work authorization and protection from deportation to individuals already in the United States whose origin countries are experiencing temporary conditions that make it unsafe for them to return. Under Biden, DHS also redesignated Haiti, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen for TPS, allowing newer arrivals from these countries to apply. These moves have made an estimated 427,000 additional individuals eligible for TPS, on top of the 319,000 who had TPS at the beginning of the Biden administration. By the end of September 2021, more than 200,000 newly eligible individuals, chiefly Venezuelan, had applied, and about 16,000 had been approved, while most of the remaining applications were pending adjudication.

Table 1. Temporary Protected Status Holders and Newly Eligible Population, 2021

Sources: Jill H. Wilson, Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2021), available online; U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), “Designation of Venezuela for Temporary Protected Status and Implementation of Employment Authorization for Venezuelans Covered by Deferred Enforced Departure,” Federal Register 86, no. 44 (March 9, 2021): 13574-81, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Syria for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 86, no. 52 (March 19, 2021): 14946-52, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Burma (Myanmar) for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 86, no. 99 (May 25, 2021): 28132-37, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Yemen for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 86, no. 129 (July 9, 2021): 36295-302, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Somalia for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 86, no. 138 (July 22, 2021): 38744-53, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Haiti for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 86, no. 146 (August 3, 2021): 41863-71, available online.

The Biden administration has also lifted some of the legal impediments to eligibility for some asylum seekers. Attorney General Merrick Garland in June reversed Trump-era legal opinions that made it almost impossible to seek asylum on grounds of fears of domestic or gang violence, or based on the past persecution of a family member. In the five months before these attorney general reversals (December 2020 through May 2021), the average monthly asylum approval rate in immigration courts was 30 percent. The rate climbed to 49 percent in the five months after (July through December).

Following the withdrawal of U.S. troops and the takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban last summer, the United States airlifted 124,000 people out of the country, the largest such airlift in U.S. history. As part of that humanitarian effort, DHS paroled about 70,000 Afghan nationals into the United States for a period of two years. Some already had pending applications for other U.S. visas, while others did not but were categorized as vulnerable and thus made eligible for parole. Parole provides protection from deportation and eligibility for work authorization. Afghan parolees have also been granted some benefits that typical parolees do not receive, including financial and medical assistance from the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) and access to services provided by nonprofit refugee resettlement agencies. Beyond those who were evacuated, more than 35,000 Afghans, still abroad, have since applied for parole. Questions remain about how Afghan humanitarian parolees will transition to permanent residence, given that parole is intended to be temporary but for many, returning to Afghanistan is perhaps impossible. The extension of parole has nevertheless proven an important first step.

In June, USCIS announced it would make certain petitioners for U visas eligible for a four-year, renewable grant of deferred action, another humanitarian protection that allows recipients to stay in the United States and apply for work authorization. U visas are available to crime victims who assist law enforcement. This option is available for U visa petitioners who have submitted all necessary documents, are residing in the United States, and are not risks to national security or public safety. The new protections could benefit up to 284,000 individuals with pending U visa petitions as of September 31, 2020. Currently, petitioners wait about four years, with no legal status, to have their petitions reviewed. The Trump administration had announced its intent to deport some petitioners.

Combining the number of individuals newly eligible for TPS, current active TPS holders, and U visa petitioners newly eligible for deferred action, up to 1,030,320 million noncitizens could now receive protection from deportation and authorization to work in the United States.

Finally, Biden set a target of 125,000 refugee admissions in FY 2022, the highest admissions cap since FY 1993 and a sharp reversal from the 15,000 ceiling set in FY 2021 by Trump. This action sent an important signal to the world of the United States’ renewed commitment to refugee resettlement, but the administration is struggling to come anywhere close to meeting that goal. Just 3,268 refugees had been resettled during the first three months of the fiscal year. This slow pace is partially due to the diversion of resettlement resources to serving Afghan evacuees, as well as the dismantling of the resettlement network during the Trump administration.

Legal Immigration

The Biden administration has acted to remove some of the obstacles for entry to the United States and extension of benefits to those immigrants already in the country that were put in place under the prior administration.

Public Charge

One such obstacle was the Trump administration’s public-charge rule, which made it more difficult for lower-income migrants to gain permanent residence (also known as getting a green card) and extend or change their status. Under the rule, factors such as income, age, and education were considered to determine whether applicants were likely to become public charges. The Biden administration avoided the drawn-out process of rescinding the Trump rule and promulgating a new one. Instead, it simply dropped the government’s appeals of court orders against the Trump rule and issued a final rule on the basis of a court order vacating the Trump rule. The final rule directs USCIS to again base its public-charge determinations on regulations that were first published in 1999. In conjunction with this change, DHS also withdrew a proposed Trump rule that would have required U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents sponsoring family members for green cards to submit additional financial information and would have made it more difficult for people who had recently received means-tested public benefits to act as sponsors.

These changes will potentially impact hundreds of thousands of green-card aspirants and their families. MPI estimated in 2018 that 69 percent of recent green-card recipients had at least one negative factor that would count against them in a public-charge determination, and 43 percent had at least two. In addition, the public-charge changes have had a “chilling effect” on the number of immigrants willing to use public benefits for which they are eligible. MPI found that between 2016 and 2019, participation in certain public benefits programs declined more quickly for noncitizens than for U.S. citizens. It may take time to dispel the chilling effects, however. One study by the nonprofit No Kid Hungry found that as of September 2021, six months after the public-charge rule reversal, 41 percent of respondents, who were either immigrants or had immigrant family members, believed that applying for public benefits could be detrimental to immigration applications.

Travel Bans

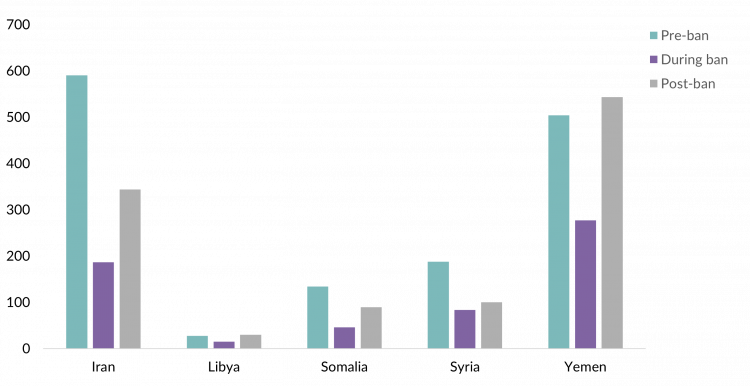

One of Biden’s first actions upon taking office was rescinding the Trump travel bans issued in 2017 and 2020, which had prevented, to varying degrees, nationals of 13 countries from traveling to the United States. The Biden administration is also allowing those denied visas due to the bans to reapply, an unusual step that speaks to the desire to fully undo one of the Trump administration’s most controversial actions. Once the bans were lifted, visa issuance to the nationals of the five countries that were subject to the broadest restrictions for the longest periods of time jumped—between 20 and 101 percent—even though pandemic-era slowdowns in visa issuance mostly prevented the return to pre-ban levels.

Figure 3. Average Monthly Immigrant Visa Issuance, Before, During, and After 2017 Travel Ban

Note: “Pre-ban” encompasses average monthly visa issuance between October 2013 and November 2017. “During ban” includes the average monthly visa issuance between December 2017 (when the Supreme Court allowed the travel ban to fully go into effect) and January 2021. “Post-ban” ranges from February 2021 through November 2021.

Sources: MPI analysis of U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, “Monthly Immigrant Visa Issuance Statistics,” accessed January 12, 2022, available online; MPI analysis of U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Report of the Visa Office (Washington, DC: Department of State, multiple years), available online.

Reducing Administrative Barriers

In addition to these headline-generating actions, other small-bore, more technical actions at USCIS and the State Department have also helped tackle some of the administrative barriers to accessing immigration benefits. While case backlogs continue to grow—the USCIS backlog reached 8 million at the end of FY 2021, and U.S. consulates have not yet returned to their pre-pandemic capacity—these changes will start to mitigate some challenges.

For example, a portion of changes undertaken by the Biden administration in this area address symptoms of slow-moving consular processes and lengthy backlogs. Consular officers can now waive in-person visa interviews for certain temporary workers, those applying for nonimmigrant visas in the same classifications, student-visa applicants who have previously been issued any type of visa, and certain repeat immigrant visa applicants who were not able to use their original visas due to pandemic restrictions. Within the United States, USCIS suspended the requirement that certain categories of nonimmigrants, including spouses of temporary high-skilled workers, submit new biometrics to extend their status. As a result of a class-action lawsuit settlement, USCIS has agreed to make spouses of H-1B and L-1 visa holders eligible for automatic extensions of work authorization. Finally, the Biden administration has started issuing work authorization valid for two years, rather than one, for people adjusting status to a green card, in recognition of ongoing processing delays at USCIS. Reducing how often immigrants must apply for work permits lessens not only the administrative but also financial burden, as applicants seeking work authorization renewal pay fees of $410.

USCIS has also rescinded several Trump administration policies that made it more difficult to access immigration benefits. USCIS will no longer require officers to rescrutinize requests for extensions of nonimmigrant visas, returning to the pre-Trump practice of deferring to the initial approval of the visa if all case facts remain the same. Similarly, USCIS officers will no longer be allowed to deny applications missing required information without first allowing applicants to correct or supplement information on their applications.

Border Enforcement

The Biden administration has struggled to articulate a clear vision for its border policy, and many of its actions there appear largely reactive. Most notably, it has continued the Trump administration’s policy of automatically expelling unauthorized border crossers without screening them for asylum eligibility—a policy implemented in March 2020 by order of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), purportedly to protect public health. Under the Title 42 policy (referencing the section of the U.S. code where it derives its authority), the Biden administration has carried out 990,000 expulsions, more than double the Trump administration’s 460,000, partly because the number of migrants arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border has spiked.

By continuing to enforce Title 42 expulsions while allowing some migrants to enter and stressing the importance of humane treatment in its narrative, the Biden administration has sent mixed messages to potential migrants and the U.S. public alike. Even as the administration formally exempted unaccompanied children from Title 42 expulsions, it searched for new ways to expel arriving families after the state government in Tamaulipas, Mexico started refusing to accept expulsions of families with young children in late January 2021. DHS began flying and busing families from this busiest sector to other sectors bordering Mexican states that would accept them, as well as expelling them via plane directly to the Mexican interior. Even with this extra effort, the administration has been unable to expel most families, as well as most single adults from countries outside Mexico and Central America. It ultimately released almost 95,000 individuals from CBP custody without formal immigration court charging documents before discontinuing that practice, in addition to those released with notices to appear in immigration courts.

Amidst this hodge-podge of policies, it is often unclear why one person is expelled and another is released, incentivizing more migrants to try their luck at crossing—sometimes repeatedly. Indeed, recidivism rates (the re-encounter of a migrant previously intercepted by CBP) soared to 27 percent in FY 2021, up from 7 percent in FY 2019. Rooting the argument for expulsion on health grounds increasingly lacks credibility, given that lawful travel at ports of entry reopened to vaccinated individuals in November 2021 (and did not close again during the recent Omicron surge).

Other administration border policy efforts have stalled. While Biden campaigned against the Remain in Mexico program, officially the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), his administration’s move to terminate it was unsuccessful. In December 2021, DHS revived MPP following a Supreme Court ruling, and as of January 10 had sent about 250 asylum seekers back to Mexico to await the outcome of U.S. asylum proceedings. The Biden administration has also tried to accelerate the reunification of families separated at the border by the Trump administration. However, out of a total of about 1,150 children who remained separated from their families as of January 2021, only 100 had been reunited as Biden’s first year ended. While off to a slow start, it seems the pace of reunifications was picking up as of December.

Pieces of a New Border Approach Emerge

Despite these fits and starts and stumbling blocks, some threads of a more sustained, changed approach to border management have emerged. The question is whether the administration will be able to weave them together, and how soon.

The administration put forth a major proposed regulation in August that would fundamentally change the way border asylum claims are handled. Under the proposed rule, USCIS asylum officers would adjudicate such claims rather than sending them to the backlogged immigration courts. This shift would allow for more timely decisions in a nonadversarial setting, allowing asylum seekers with meritorious claims to win protection faster and ensuring that those who do not qualify are more quickly removed. The rule is expected to go into effect in the coming months.

The administration is also trying to address the root causes of migration, particularly from Central America. It has increased humanitarian aid for some acute needs. It has also started a multiyear initiative through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to invest up to $300 million in local organizations to fight corruption and protect human rights, among other missions. And the U.S. Department of Labor awarded $5 million to a U.S. NGO to work with local organizations to improve workers’ rights in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The administration is further requesting that Congress appropriate $4 billion over four years for development assistance to these three countries. While it is unlikely that these long-term development efforts and others like them will decrease migration pressures immediately, if sustained, they could yield results years from now.

Recognizing that migration to the U.S.-Mexico border has become a hemispheric phenomenon, the Biden administration has also pursued a regional migration management strategy. For example, in October, Secretary of State Antony Blinken co-chaired a meeting on migration with representatives of 16 other governments in the region, who agreed to collaborate to create a collective development strategy. During the North American Leaders’ Summit in November, the United States, Mexico, and Canada committed to developing a regional compact on migration and protection, promoting labor mobility, and bolstering humanitarian protection systems, among other pledges. A U.S. effort to address migration collectively and through partnerships with countries across the Americas has not before been advanced to this degree.

Finally, the administration has taken initial steps to increase Central Americans’ access to legal pathways to the United States, such as H-2B visas for nonagricultural seasonal workers. In both FY 2021 and 2022, DHS and the Department of Labor set aside a portion of H-2B visas for nationals of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras; it did the same for Haiti for FY 2022.

More Executive Actions Ahead

Biden’s hopes for delivering on his promise to legalize the country’s 11 million unauthorized immigrants have been pinned on the fate of his key legislative effort, the Build Back Better Act. Though the massive bill passed the House, it remains stalled in the Senate, with few prospects for passage. Even if that legislation ever passes Congress in some form, it looks less and less likely to include immigration provisions.

Given the reality of a Congress that has proven itself unwilling and unable over the past two decades to tackle significant change to the immigration system, it remains likely that future efforts will have to rely on executive action by the president. Biden and his administration, in their first year, have demonstrated a level of commitment to immigration action that rivals Trump’s. As Biden works to undo many of Trump’s changes and craft an immigration system that meets his priorities and those of his allies, the system’s ability to withstand and adapt to partisan pendulum swings will surely be tested.

Sources

Capps, Randy, Mark Greenberg, Michael Fix, and Jie Zong. 2018. Gauging the Impact of DHS’ Proposed Public-Charge Rule on U.S. Immigration. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Capps, Randy, Michael Fix, and Jeanne Batalova. 2020. Anticipated “Chilling Effects” of the Public-Charge Rule Are Real: Census Data Reflect Steep Decline in Benefits Use by Immigrant Families. Migration Policy Institute commentary, December 2020. Available online.

Castillo, Andrea. 2021. Biden Administration Halts Immigrant Family Detention for Now. Los Angeles Times, December 17, 2021. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Jessica Bolter. 2021. Legal Snags and Possible Increases in Border Arrivals Complicate Biden’s Immigration Agenda. Migration Information Source, February 25, 2021. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Randy Capps. 2021. Biden Immigration Enforcement Priorities Emphasize a Multi-Dimensional View of Migrants. Migration Information Source, October 28, 2021. Available online.

Fox, Ben. 2021. US Has Reunited 100 Children Taken from Parents under Trump. Associated Press, December 23, 2021. Available online.

Johnson, Tae and Troy Miller. Memorandum from the Acting Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the Acting Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Civil Immigration Enforcement Actions in or Near Courthouses. April 27, 2021. Available online.

Marcelo, Philip and Amy Taxin. 2021. Hundreds of Afghans Denied Humanitarian Entry into US. Associated Press, December 30, 2021. Available online.

Matter of A-B-. 2021. 28 I&N Dec. 307. Attorney General, June 16, 2021. Available online.

Matter of L-E-A-. 2021. 28 I&N Dec. 304. Attorney General, June 16, 2021. Available online.

Mayorkas, Alejandro. 2021. Memorandum from the Secretary of Homeland Security to Tae D. Johnson, Acting Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; Troy A. Miller, Acting Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection; Ur M. Jaddou, Director, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; Robert Silvers, Under Secretary, Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans; Katherine Culliton-González, Officer for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties; and Lynn Parker Dupree, Chief Privacy Officer, Privacy Office. Guidelines for Enforcement Actions in or Near Protected Areas. October 27, 2021. Available online.

Migration Policy Institute (MPI) Migration Data Hub. N.d. U.S. Annual Refugee Resettlement Ceilings and Number of Refugees Admitted, 1980-Present. Available online.

Monyak, Suzanne. 2021. Limited Operations at US Consulates Keep Visa Holders on Edge. Roll Call, December 22, 2021. Available online.

No Kid Hungry. 2021. Public Charge Was Reversed— But Not Enough Immigrant Families Know. Washington, DC: No Kid Hungry. Available online.

O’Toole, Molly. 2021. ICE to Close Georgia Detention Center where Immigrant Women Alleged Medical Abuse. Los Angeles Times, May 20, 2021. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2021. Asylum Decisions. Accessed January 13, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). 2021. USAID Announces Centroamérica Local Initiative to Empower Local Partners in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Press release, November 4, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2022. Chapter 5 - Bona Fide Determination Process. Updated January 13, 2022. Available online.

---. 2021. Bona Fide Determination Process for Victims of Qualifying Crimes, and Employment Authorization and Deferred Action for Certain Petitioners. Policy alert, June 14, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Deference to Prior Determinations of Eligibility in Requests for Extensions of Petition Validity. Policy alert, April 27, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Employment Authorization for Certain Adjustment Applicants. Policy alert, June 9, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Employment Authorization for Certain H-4, E, and L Nonimmigrant Dependent Spouses. Policy alert, November 12, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Number of Form I-918, Petition for U Nonimmigrant Status - By Fiscal Year, Quarter, and Case Status. October 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Requests for Evidence and Notices of Intent to Deny. Policy alert, June 9, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. USCIS Temporarily Suspends Biometrics Requirement for Certain Form I-539 Applicants. News release, May 13, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2021. For First Time, DHS to Supplement H-2B Cap with Additional Visas in First Half of Fiscal Year. Press release, December 20, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds; Implementation of Vacatur. Federal Register 86, no. 48 (March 15, 2021): 14221-29. Available online.

---. 2021. DHS, VA Announce Initiative to Support Noncitizen Service Members, Veterans, and Immediate Family Members. Press release, July 2, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics. N.d. Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) Report on December Cohort. Accessed January 18, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General (OIG). 2022. USCIS’ U Visa Program Is Not Managed Effectively and Is Susceptible to Fraud (Redacted). Washington, DC: DHS OIG. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security and U.S. Department of Justice, Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR). 2021. Procedures for Credible Fear Screening and Consideration of Asylum, Withholding of Removal, and CAT Protection Claims by Asylum Officers. Federal Register 86, no. 159 (August 20, 2021): 46906-50. Available online.

U.S. Department of Labor. 2021. US Department of Labor Awards $5M Grant to Help Agricultural Supply Chain Workers in Honduras, Guatemala; Garment Workers in El Salvador. Press release, December 20, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of State. 2021. Joint Statement of the Ministerial Meeting in Bogotá on the Causes and Challenges of Migration. Press release, October 29, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). 2021. ICE Directive 11032.4: Identification and Monitoring of Pregnant, Postpartum, or Nursing Individuals. July 1, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. ICE Directive 11005.3: Using a Victim-Centered Approach with Noncitizen Crime Victims. August 10, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Detention Management—Detention Statistics, multiple years. Updated January 10, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Refugee Processing Center. 2021. Admissions & Arrivals—Refugee Admissions Report. Updated December 31, 2021. Available online.

White House. 2021. Fact Sheet: Key Deliverables for the 2021 North American Leaders’ Summit. Press release, November 18, 2021. Available online.