You are here

Biden at the Two-Year Mark: Significant Immigration Actions Eclipsed by Record Border Numbers

President Joe Biden at the U.S.-Mexico border. (Photo: Tia Dufour/DHS)

Editor's Note: This article was updated on February 2, 2023 to correct the number of nonimmigrant (temporary) visas issued in FY 2022.

On his first day in office, President Joe Biden announced sweeping plans to reform decades-old U.S. immigration laws, undo many of the restrictive policies of the predecessor Trump administration, and provide a pathway to legal status for the nation’s estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants. Two years later, few of those ambitions have been realized and the administration presents an image of one struggling to find its footing on immigration. Despite the slim Democratic majority in both houses of Congress during the president’s first two years, lawmakers remained paralyzed on immigration and did not advance the Biden agenda. Meanwhile, Republican state officials successfully used the courts to halt many of the administration’s executive efforts.

However, the Biden administration, like the predecessor Trump and Obama presidencies, has relied on the toolbox of executive actions to implement its priorities and transform key elements of the sprawling immigration system. In fact, midway through its term, the Biden administration has far outstripped the pace of executive actions taken during the Trump administration, which was perceived as the most activist yet on immigration. From January 20, 2021 through January 19, 2023, the Biden administration took 403 immigration-related actions, according to calculations by the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), putting it on track to soon overtake the 472 immigration-related executive actions MPI counted for all four years of the Trump administration.

While some executive actions have been stalled by the courts, Biden’s measures have nonetheless affected the lives of hundreds of thousands of immigrants, including many seeking protection. Among these changes were more targeted interior enforcement; regulations to fortify the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which provides work permits and protection from deportation to unauthorized immigrants who arrived as minors; expanding humanitarian protection through Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and other programs; and unblocking legal immigration channels that had been chilled by the pandemic.

Yet the daunting challenges at the U.S. southern border, which is seeing record levels of migrant encounters by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), have overshadowed actions elsewhere in the immigration realm. Federal officials and border communities have been overwhelmed, and the perception of a chaotic border has been used as a political cudgel, including through the publicized busing of asylum seekers and other migrants to New York, Washington, DC, and other cities. In fiscal year (FY) 2022, authorities recorded 2.4 million encounters of migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border without authorization, the most ever. The Biden administration’s attempts to end two hallmark Trump border policies—the Migrant Protection Protocols (informally known as Remain in Mexico) and Title 42 expulsions, which prevent access to asylum—have been stalled by the courts, only muddying the waters at the southern border.

Ironically, this border surge may have been partly prompted by the administration’s actions elsewhere to shield immigrants from deportation and provide humanitarian protections, as migrants expected a warm welcome in the United States after four years of Trump. Biden’s ambitious immigration agenda, therefore, may have contributed to one of his most vexing policy challenges. This article assesses the Biden administration’s major immigration actions during its first two years in office, concentrating on interior enforcement, legal immigration, humanitarian protection, and border enforcement.

Interior Enforcement: A Quiet Transformation

While actions at the U.S.-Mexico border have drawn intense media and political attention, it is in the realm of immigration enforcement in the U.S. interior that the Biden administration has sought to carry out an important shift, often with little public recognition.

Biden entered office amid heightened tension between immigration enforcement authorities empowered by the Trump administration and his Democratic base, parts of which had called for “abolishing” U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). While Biden distanced himself from more radical demands, his administration has attempted a wholesale realignment of immigration enforcement within the U.S. interior. Through new prosecutorial discretion guidelines, it directed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to target its enforcement resources towards recent border crossers and migrants who present threats to national security or public safety, rather than the Trump administration’s approach of going after anyone in the country without authorization.

Republican-led states challenged these guidelines, which remain paused pending Supreme Court action. Beyond major implications for the administration’s leeway in setting its enforcement priorities, the high court’s ruling could affect how DHS reconciles its mandate to enforce immigration laws and the finite resources that Congress provides to execute them.

While there was some speculation that the court’s halting of the revised enforcement priorities would lead to a surge in deportations, numbers have remained far below peak years, suggesting that the administration has in reality transitioned to a new enforcement approach. ICE conducted more than 72,100 removals in FY 2022, an increase of 22 percent over the 59,000 in FY 2021 but still a fraction of the average 233,000 annual removals during the Trump administration and the 344,000 removals per year during Obama’s term.

Moreover, arrests from the U.S. interior account for only a small component of all removals. Just 28,200 noncitizens in FY 2022 were removed from the interior after initially being arrested by ICE, while the remainder were border arrivals initially processed by CBP. In comparison, an average 81,000 annual interior removals occurred during the Trump administration and about 155,000 per year under Obama.

ICE’s total arrests—not just those leading to removals—were largely driven by border arrivals. In FY 2022, ICE conducted nearly 143,000 immigration arrests, more than 96,000 (67 percent) of which were noncitizens without criminal convictions or charges, compared to 39 percent in FY 2021. Migrants arriving at ICE offices from the border drove this increase in administrative arrests, as ICE issued charging documents when noncitizens appeared for check-in appointments.

Detention

A major issue in the ongoing litigation over the enforcement priorities is DHS’s legal requirement to detain every removable noncitizen, which would likely be unfeasible. Congress mandated ICE to maintain its daily detention capacity at 34,000, which was a rejection of the Biden administration's proposed decrease to 25,000 beds. ICE detained an average of nearly 22,600 people daily in FY 2022—down from a high of 50,200 in FY 2019—and recorded nearly 307,000 total book-ins, of which 250,100 (81 percent) came from the border.

Figure 1. Initial Book-Ins to Detention by Agency, October 2019-August 2022

Source: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), “Detention Management,” updated January 19, 2023, available online.

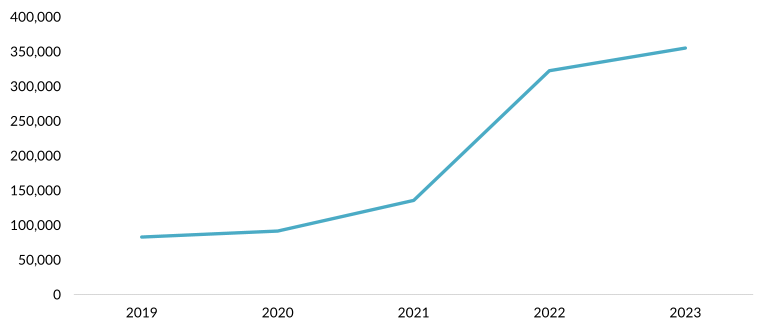

The Biden administration has dramatically increased the use of ICE’s alternatives to detention (ATD) programs, which track noncitizens through a smartphone app or ankle monitor while their immigration case proceeds. Under Biden, the program has been used for migrants paroled in at the border. ICE reported about 323,000 people enrolled in ATDs in FY 2022, up from 136,000 in FY 2021 and 23,000 in FY 2014. (Concerns have been raised about the completeness of the data.)

Figure 2. Migrants Enrolled in Alternatives to Detention Programs, FY 2019-23

Note: Data for fiscal year (FY) 2023 run through January 14, 2023.

Source: ICE, “Detention Management.”

Overall, ICE’s nondetained docket ballooned to 4.7 million cases in FY 2022, up from 2.4 million in FY 2018, a growth it has attributed to cases transferred from CBP. Of the 4.7 million people, 1.2 million have a final order of removal.

Immigration Courts

ICE can only remove noncitizens from the United States once immigration courts issue a final order of removal. But the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), the administrative court system housed in the Justice Department, is buckling under the weight of an unprecedented backlog, leading to millions of asylum seekers and potentially deportable noncitizens waiting in limbo. As of January, the case backlog had surpassed 2 million, more than 800,000 of which involved asylum claims. EOIR hired 104 new immigration judges in FY 2022, but the courts have been unable to keep up with the unprecedented number of cases referred from the border. EOIR received around 800,000 new cases in FY 2022, at least 300,000 more than ever before in a single year. Consequently, it now takes an average of about four years to receive a decision in an asylum case.

The administration introduced new measures in 2022 to try to get a handle on the massive backlog. First, EOIR tested removing from the court calendar lower-priority cases such as those involving individuals with applications pending before U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)—an effort consistent with the revised DHS enforcement priorities to focus on higher priority cases such as individuals with criminal records. The attorney general also reversed Trump-era decisions that restricted immigration judges’ abilities to manage their own dockets and prioritize more serious cases. In part due to these initiatives, case completions recovered rapidly from the pandemic-era low of 116,000 in FY 2021 to 312,000 cases closed in FY 2022. The courts also made progress on moving into the 21st century by mandating e-filing for newer cases involving noncitizens represented by a lawyer and shifted towards more web-based hearings.

Legal Immigration on the Rebound

The Biden administration has successfully approached pre-pandemic and pre-Trump levels of legal immigration. The country accepted about 1 million immigrants as permanent residents in FY 2022, just below the 1.1 million per year average over the last two decades and a dramatic increase from the recent low of 707,000 in FY 2020. Additionally, about 6.8 million nonimmigrant (temporary) visas for students, tourists, and short-term workers, including border crossing cards (for Mexican nationals), were issued in FY 2022, up from 2.8 million in FY 2021.

This marks a rebound from COVID-19-related consulate closures and travel restrictions as well as Trump-era policies that sought to deeply reduce legal immigration. It is all the more significant in light of ongoing U.S. labor shortages. The administration prioritized this turnaround by rolling over unused visas in family-based immigration categories to employment categories. As a result, USCIS processed double the usual yearly allotment for employment-based immigrant visas, hitting 275,000 in FY 2022.

USCIS also naturalized almost 1 million new immigrants in FY 2022, a 14-year high. More people became U.S. citizens in FY 2022 than any other year on record except 1996 and 2008. Additionally, the Biden administration rescinded a Trump-era rule that prevented noncitizens who accessed certain public benefits from becoming lawful permanent residents (also known as green-card holders), a change that the Supreme Court has allowed to stand.

Still, enormous backlogs and long waits for visa interviews continue to frustrate applicants. USCIS had 8.7 million pending applications in September 2022, an increase from 5.8 million in December 2019. The State Department has an immigrant visa interview backlog of 378,000, up from 61,000 in 2019, and wait times for nonimmigrant interviews stretch to more than 900 days at some consulates for certain visa types.

To address these issues, USCIS and the State Department have undertaken technical changes that have had significant impacts. For example, USCIS issued a rule automatically extending some work permits for 540 days, up from 180 days, while renewal applications are pending. This affected more than 400,000 work permits and prevented some noncitizens from losing their jobs due to long wait times for processing applications. Similarly, the agency extended the validity of green cards for two years while renewal applications are pending, meaning fewer legal permanent residents would lack proof of their status while waiting for application processing. The State Department also extended its pandemic-era practice of waiving in-person interviews for certain cases. Consequently, about half of nonimmigrant visas issued in FY 2022 were approved without an interview.

Humanitarian Protection: New Programs, but Refugee Resettlement Stalled

In response to huge numbers of border arrivals and refugee flows from Afghanistan and Ukraine, the Biden administration embarked on a series of innovative and unconventional efforts to offer humanitarian protection. It has, however, notably fallen short of its plans to significantly revive refugee resettlement after years of cuts during the Trump administration. While the Biden efforts may have led to rapid protections for many, the programs have tended to be temporary and exclude people in need of protection from other parts of the world.

Temporary Statuses

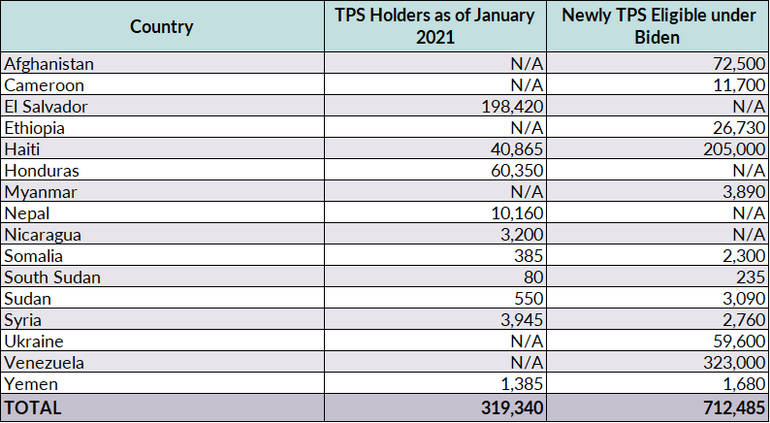

Biden has expanded categories of people eligible for some form of humanitarian protection, such as TPS, which provides work permits and deportation relief to already U.S. present nationals of countries where conditions do not permit return. The Biden administration has designated six new countries for TPS (Afghanistan, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Myanmar, Ukraine, and Venezuela) and redesignated six countries (Haiti, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen).

These designations mean that Biden has made an additional 712,000 immigrants already in the United States eligible for TPS. Delays at USCIS have affected approvals, but as of November 2022 nearly 537,000 people had TPS.

Table 1. Temporary Protected Status Holders and Newly Eligible Population, 2023

Note: Because an unknown number of immigrants who were eligible for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) at the beginning of the Biden administration have obtained other legal status, died, or left the country, the precise number of currently eligible individuals is not publicly available.

Sources: Jill H. Wilson, Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2022), available online; U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), “Designation of Venezuela for Temporary Protected Status and Implementation of Employment Authorization for Venezuelans Covered by Deferred Enforced Departure,” Federal Register 86, no. 44 (March 9, 2021): 13574, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Syria for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 86, no. 52 (March 19, 2021): 14946, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Burma (Myanmar) for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 86, no. 99 (May 25, 2021): 28132, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Yemen for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 86, no. 121 (July 9, 2021): 36295, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Somalia for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 86, no. 138 (July 22, 2021): 38744, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Haiti for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 86, no. 146 (August 3, 2021): 41863, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Burma (Myanmar) for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 186 (September 27, 2021): 58515, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Sudan for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 75 (April 19, 2022): 41863, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Ukraine for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 75 (April 19, 2022): 23211, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of South Sudan for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 42 (May 3, 2022): 41863, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Afghanistan for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 98 (May 20, 2022): 30976, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Cameroon for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 109 (June 7, 2022): 34706, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Syria for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 146 (August 1, 2022): 46982, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Haiti for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 86, no. 146 (August 3, 2021): 41863, available online; USCIS, “Continuation of Documentation for Beneficiaries of Temporary Protected Status Designations for El Salvador, Haiti, Nicaragua, Sudan, Honduras, and Nepal,” Federal Register 87, no. 220 (November 16, 2022): 68717, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Ethiopia for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 237 (December 12, 2022): 76074, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Yemen for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 88, no. 1 (January 1, 2023): 94, available online.

DACA and Deferred Action

The administration also used its executive authority to issue a federal rule on DACA, which was originally instituted under the Obama administration through a policy memorandum rather than by regulation, making it potentially vulnerable to legal challenges that Republican-led states have pursued for years. DACA provides young adults who have been in the United States since they were children with work authorization and relief from deportation, like TPS. As of September 2022, 589,660 young adults had DACA. The new rule has been challenged in federal court in Texas, which is expected to rule sometime in this spring.

Other groups have also been granted deferred action under Biden, including Liberians, applicants deemed to have bona fide claims for U visas (created for survivors or witnesses of crimes), and abused children who applied for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status. As of January, workers who have brought claims of workplace violations are also eligible to apply for deferred action. Data on these grantees are not readily available.

Parole

Immigration parole is another remedy the administration has used to provide eligibility for work authorization and temporary protection from deportation. Facing record arrivals at the southern border, DHS in FY 2022 allowed some 378,000 people into the United States for a limited duration via parole.

Perhaps more notable, though, were special parole programs created for nationals of certain countries. As the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in 2021, U.S. officials paroled 70,000 Afghan nationals into the United States for a two-year period as part of Operation Allies Welcome. In 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the administration launched the similar Uniting for Ukraine (U4U) parole program, which paired U.S.-based sponsors with fleeing Ukrainians. The government quickly met the president’s goal of welcoming 100,000 Ukrainians through legal pathways including family-sponsored green cards and tourist and student visas. As of January, the United States had admitted more than 229,000 Ukrainians, 102,000 of whom came through U4U.

In October 2022, amid a rapid increase in the number of Venezuelans arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border, the administration created a process to parole 24,000 Venezuelans into the United States. Unlike previous initiatives, this was triggered by authorities’ inability to expel Venezuelans due to strained diplomatic relations with that country. Approximately 11,000 Venezuelans had been paroled in at as of this writing. The administration in January extended the program to include nationals of three other countries with similarly strained diplomatic relations: Cubans, Haitians, and Nicaraguans. The new policy rests on the cooperation of the Mexican government, which has agreed to accept up to 30,000 expelled migrants of all four nationalities per month.

Deferred action, TPS, and parole do not provide a pathway to lawful permanent residence, which only Congress can grant. Unless parole is extended or recipients find another pathway to lawful status, these noncitizens may face deportation proceedings when their statuses expire. The Afghan Adjustment Act would create a pathway to permanent status for displaced Afghans, but it has not advanced in Congress. There has not yet been legislation to offer permanent status to paroled Ukrainians. Many immigrants hoping to stay in the United States will need to apply for asylum or another form of lawful status, but the affirmative asylum backlog at USCIS already was a crushing 607,000 applications as of December 2022.

Slow Refugee Resettlement

A major Biden administration commitment has been to rebuild the refugee resettlement system largely dismantled under Trump, but progress has been slow. In FY 2022, the administration resettled just 25,500 refugees, far short of its 125,000 goal but an increase from the 11,400 resettled in FY 2021. The administration is expected to again miss its target by a wide mark in FY 2023; only 6,800 refugees had been resettled by December 31, meaning the pace would need to increase to an average of 13,138 refugees monthly to reach 125,000 by the end of the fiscal year on September 30.

The State Department and USCIS have increased hiring and adopted technology to try to speed resettlement, but they were also tasked with responding to Afghan evacuees and the growing panoply of parole programs. The administration’s apparent focus on TPS, deferred action, and parole at the expense of refugee resettlement, which leads to lawful permanent residence, only adds to the pool of immigrants in limbo.

Perhaps acknowledging the challenges with traditional refugee resettlement and to build public support, the administration in early 2023 began piloting a program allowing individual U.S. citizens and green-card holders to privately sponsor refugees. The Welcome Corps program, which is designed to resettled at least 5,000 refugees in the first year, builds upon elements of programs for Afghans, Ukrainians, and others, and could represent a sea change in U.S. resettlement.

At the Border, a Challenge like Never Before

In many ways, the impact of the Biden administration’s efforts in the U.S. interior have been eclipsed by an historic influx at the southern border, which has given critics potent political talking points. Earlier this month, Biden for the first time publicly acknowledged the heavy toll record border arrivals have taken on his presidency.

While migrants may perceive the United States as more welcoming under Biden and are drawn by U.S. labor market needs, there are more than pull factors at play. Push factors in many Latin American and Caribbean countries such as political instability, violence, corruption, poor governance, and deep economic malaise in the aftermath of the pandemic are drivers for emigration.

Beyond larger numbers, the profile of who is arriving at the border has become far more diverse. For the first time in U.S. history, CBP in FY 2022 encountered more Venezuelans, Cubans, and Nicaraguans than Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Salvadorans. Significant numbers of Brazilians, Ecuadorians, Haitians, Ukrainians, Indians, and Turks also were encountered. In the first three months of FY 2023, Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans represented 35 percent of all 718,000 border encounters. Title 42, which allows authorities to expel asylum seekers and other arriving migrants without processing, ironically has incentivized migrants to make multiple crossing attempts since they face little penalty for doing so.

While Title 42 has received huge attention from immigrant-rights activists and the media, its impact has been somewhat exaggerated. Its use has steadily declined since enacted by the Trump administration in March 2020, used for just 20 percent of all migrants processed in December 2022, a new low. By comparison, 80 percent of migrants in December were processed under the traditional immigration code (Title 8). Exceptions for children, particular nationalities, and people with certain vulnerabilities meant that for all of FY 2022, most migrants halted at the border were processed via Title 8, not expelled under Title 42 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Legal Authority Used by Customs and Border Protection at the U.S.-Mexico Border, FY 2020-22

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “Nationwide Encounters,” updated December 14, 2022, available online.

Announcement of New Border Policies

Acknowledging the unsustainable level of arrivals at the U.S. southern border, the Biden administration this month announced a new set of policies, including the previously discussed parole program for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans, and the expulsion of up to 30,000 nationals from these four countries per month. As was the case after the Venezuela program in October, encounters of these nationalities declined rapidly following the announcement, though it remains to be seen if that trend will continue.

All other border crossers are now required to use an app, CBP One, to schedule appointments at ports of entry to apply for humanitarian exceptions to Title 42, and then for asylum or other relief after the public-health order is lifted. The Departments of Justice and Homeland Security also plan to issue a rule to incentivize people to use the new appointment system and to “place certain conditions on asylum eligibility for those who fail to do so.” Although details of the new rule are yet to be released, the administration’s announcement suggests there will be a rebuttable presumption of ineligibility for asylum and that, barring exceptions, asylum seekers will be expected to seek protections in other countries they transit through. Advocates have compared the plan to Trump’s “transit ban,” which attempted to severely limit access to asylum in the United States but was struck down by courts.

The fate of the expected rule remains to be seen. Other questions also remain unanswered: Will the new measures reduce the number of people arriving before Title 42 ends? What will happen to migrants who show up at the border without an appointment? And what are Mexico’s conditions for accepting those expelled at the border?

Regardless of the upcoming Supreme Court ruling, Title 42 will be lifted eventually. Once that happens, all migrants apprehended at the border will be processed under Title 8 and many will likely be subjected to expedited removal, which allows for their rapid expulsion unless they express a fear of persecution and pursue an asylum claim.

In this post-Title 42 world, a new rule promulgated in April 2022 will be an important tool for processing asylum claims at the border. The rule is meant to facilitate a faster determination of such claims by asylum officers rather than backlogged immigration courts. Its implementation has been slow and limited, perhaps understandably given the historic pace of border arrivals. If the new restrictions lead to a significant decrease in arrivals, a reformed asylum process may finally allow the administration breathing space to create a fair and efficient asylum system that offers lasting protection to those who qualify under U.S. law and swiftly removes those who do not. Such a future may seem far off, given the administration’s current border challenges. But Biden’s term is only half done, and an asylum system that has the public’s full confidence would be a notable achievement.

An Immigration Legacy in the Making

Midway through its term, the Biden administration has notched some significant advances. The quiet transformation of immigration enforcement in the U.S. interior, use of parole and other mechanisms to grant humanitarian protection, and restoration of legal immigration to pre-pandemic levels will have a lasting legacy.

Yet on the whole, its work appears unfinished. The record numbers of arrivals at the border have become a constant challenge that have prevented the administration from focusing on other efforts. Without more order there, significant legislative action on immigration faces an uphill battle.

Meanwhile, congressional inaction has forced the administration to retreat from its expansive legislative ambitions, and narrow Republican control of the U.S. House of Representatives may make even piecemeal reforms hard to achieve. Thus, the administration will continue to rely on its unmatched embrace of executive action, even while it responds to legal challenges that it has come to expect.

The authors thank Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh, Jessica Bolter, and Caitlin Davis for their research assistance.

Sources

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). 2022. ACLU Urges Biden Administration Not to Revive Illegal Trump-Era Transit Ban Gutting Asylum Protections. Press release, December 13, 2022. Available online.

Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR). 2022. FY 2022 Decision Outcomes. Washington, DC: EOIR. Available online.

Hackman, Michelle. 2022. Ukrainians Are Offered Haven in U.S. While Others Wait. The Wall Street Journal, December 21, 2022. Available online.

Moodie, Alison. 2023. Current Status of U.S. Visa Services by Country - January 2023. Boundless, January 9, 2023. Available online.

Passel, Jeffrey S. and D’Vera Cohn. 2022. After Declining Early in the COVID-19 Outbreak, Immigrant Naturalizations in the U.S. Are Rising Again. Pew Research Center, December 2, 2022. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2022. FY 2022 Seeing Rapid Increase in Immigration Court Completions. TRAC, September 16, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. ICE’s Sloppy Public Data Releases Undermine Congress’s Transparency Mandate. TRAC, September 20, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Immigration Court Backlog Now Growing Faster Than Ever, Burying Judges in an Avalanche of Cases. TRAC, January 18, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Immigration Court Backlog Tool. Updated December 2022. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2022. Count of Active DACA Recipients by Month of Current DACA Expiration as of September 30, 2022. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2022. USCIS Extends Green Card Validity Extension to 24 Months for Green Card Renewals. Press release, September 28, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. USCIS Increases Automatic Extension Period of Work Permits for Certain Applicants. Press release, May 3, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Fiscal Year 2022 Progress Report. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection. 2022. Custody and Transfer Statistics FY 2022. Updated November 14, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Nationwide Encounters. Updated December 14, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). 2022. ICE Annual Report Fiscal Year 2022. Washington, DC: ICE. Available online.

---. 2023. Detention Statistics. Updated January 19, 2023. Available online.

U.S. State Department, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, Refugee Processing Center. 2022. Admissions & Arrivals. Updated December 31, 2022. Available online.