You are here

Can Return Migration Revitalize the Baltics? Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania Engage Their Diasporas, with Mixed Results

Flags of the three Baltic states, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, on display in Riga, Latvia. (Photo: Pablo Andrés Rivero)

In the Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—high emigration rates and shrinking, aging populations are leading to an impending demographic crisis. The region is one of the most rapidly depopulating in the world, and according to United Nations estimates, by 2050 Latvia’s population could shrink by 22 percent, while those in Lithuania and Estonia could decline by 17 percent and 13 percent, respectively.

Population shrinkage in nothing new in the already sparsely populated Baltics: during periods of Nazi and Soviet occupations, the region suffered from tremendous loss of residents. After the collapse of the Soviet Union and opening of the borders to the West, the Baltics experienced significant emigration. Later, when all three Baltic states became members of the European Union in 2004, free movement within the bloc encouraged emigration; spurred by the 2009 global financial crisis, the region lost even more of its population. Despite some modest return migration from the United Kingdom given the uncertainty surrounding Brexit, the largest Baltic country, Lithuania, was home to 2.8 million people as of 2019, while the population in Latvia totaled 1.9 million, and that of Estonia 1.3 million.

All three Baltic states have sizeable diasporas, with an estimated 20 percent of Latvians living abroad, and Lithuania and Estonia estimating 17 percent and 15 percent of their nationals, respectively, live outside their country of birth. While precise numbers are difficult to obtain, given free movement within the European Union, the Baltics are feeling the effects of these high emigration rates, and in turn are exploring different ways to woo back nationals and establish or solidify ties with members of the diaspora, as this article explores. Of the three countries, Estonia is proving the most successful in these and other areas, while Latvia appears to be ignoring the looming demographic crisis and lacking an immigration plan.

A Region on the Brink of Demographic Crisis

By 2050, according to World Bank estimates, the working-age population in all three countries will be at an all-time low; the Baltic Center for Investigative Journalism (Re:Baltica) predicts that by 2030 almost half of Latvian residents will be over the age of 50. The situation is so serious that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has repeatedly called upon the Baltic governments to address their demographic challenges, as the resulting lack of a labor force has significantly impacted the region’s potential for future economic growth.

Each of the Baltic states has responded to the situation somewhat differently—and with varying levels of alarm—by promoting different approaches to immigration, encouraging return migration, and implementing policies to engage with the diaspora. Estonia has focused on branding itself the capital of digital innovation, for example boasting it is the “new digital nation” because of its offer of e-Residency, as one means to encourage migration or return migration. As of January 1, 2019, Latvia became one of a handful of countries to implement a separate diaspora law to foster engagement from a wide net of diaspora members: even those individuals who feel some affinity to Latvia while not necessarily tracing their lineage back to the country are considered part of the diaspora. And Lithuania is actively encouraging, through a specifically dedicated web platform and various programs, the return of diaspora members. These approaches, among others, have garnered disparate results—and mixed responses from the public.

High Emigration Rates and a Reluctance to Accept Non-EU Migrants

The Baltic states have been very sensitive to immigration from outside the European Union and stringent about maintaining their ethnic balance, as well as protecting their languages and cultures. This sensitivity reflects the region’s contentious history with the Soviet Union, including population transfers and enduring effects of Russification policies—which sought to impose Russian language and culture in an effort to eradicate the Baltic languages and heritage through cultural assimilation. Further, the Baltic states have been less than successful in managing integration and social cohesion issues. The Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) has continuously noted the anti-immigrant sentiment that exists in all three Baltic countries.

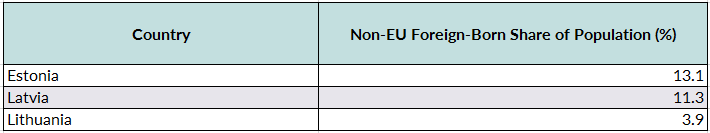

Table 1. Non-European Union Foreign-Born Share of Population, (%), 2018

Source: Eurostat, “Foreign-Born Population by Country of Birth,” accessed May 6, 2019, available online.

In addition, the Baltics have been very hesitant to accept refugees or grant refugee status to asylum seekers from the Middle East and North Africa. Under a 2015 EU plan to allocate asylum seekers more equitably across the bloc, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were obliged to accept 1,679 refugees in total. Despite this relatively small number, the issue of refugees has been deeply unpopular in the Baltics, contributing to the governments’ sluggish response in meeting quotas and hesitation to pledge to take in more refugees. For example, in 2018 Latvia granted refugee status to just 23 individuals. Finally, refugees who do end up in the Baltics often move on to wealthier EU countries.

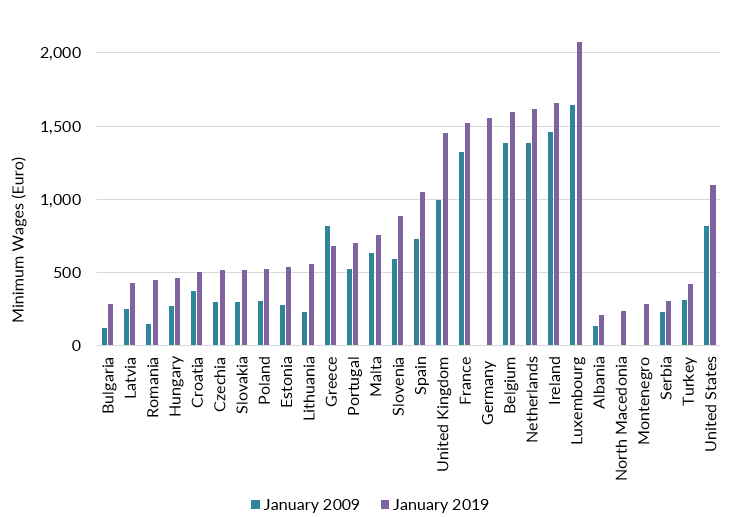

Income disparity between EU countries has been the driving force, as well, for the emigration of Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians, who leave in search of higher wages and better job opportunities. Although salaries have been rising steadily, they do not compare with the pay in more developed economies, such as in the United Kingdom, Germany, Ireland, and the Nordic countries—all of which are major destinations for Baltic emigrants. Eurostat data illustrate the growth of the minimum wage in the Baltic states between 2009 and 2019; however, the salaries pale in comparison to the minimum wages of developed EU countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Average Monthly Minimum Wages in the European Union and Select Countries, January 2009 and January 2019

Notes: Data for North Macedonia and Montenegro are from January 2017. No data were available for January 2009 from Germany, North Macedonia, and Montengero.

Source: Eurostat, “Minimum Wages, January 2009 and January 2019,” accessed April 25, 2019, available online.

Another major concern driving emigration is the inability of rising wages to keep up with inflation, as well as the perceived lack of adequate health care and social security—two principal concerns for individuals living in the Baltic states, according to the 2018 Eurobarometer survey.

Estonia: Buzzy Digital Branding Brings Some Success

Of the Baltic states, Estonia has been the most successful in improving its economic situation and in trying to come to terms with its demographic decline, recognizing it will need to encourage immigration in order to maintain population growth. Immigration is governed by the Aliens Act, which since 2008 has been amended five times, each reform making it easier for foreign workers to arrive and work in Estonia. The policy specifically targets highly qualified individuals and facilitates residency for those specialists who earn their degrees at Estonian institutions of higher education. Estonia also grants residence permits to investors and boasts the special Estonian Startup Visa, which simplifies residency procedures for non-EU investors and talent.

Estonia’s diaspora policy, known as the Compatriots Program, is managed jointly by the Ministries of Education and Culture and has been in place since 2004. The program places emphasis on Estonian language instruction abroad; preserving culture and a sense of belonging to the Estonian nation; archival work for the preservation of Estonian history; and the return of expatriate Estonians. Returning Estonians can qualify for a support payment from the Integration and Migration Foundation’s Our People program, while returning researchers can receive grants. However, Estonia is also cautious in its efforts to bring back highly skilled individuals: Bringing Talent Home, a 2010-12 return migration initiative, failed to reach its goals, and was instead perceived as highly offensive by members of the diaspora who did not meet the program’s requirements. Instead, the Estonian government has partnered with several nongovernmental initiatives to attract talented foreign workers and encourage their settlement. For example, International House Estonia is a one-stop agency that helps newcomers settle, while the Career Hunt initiative provides an all-expense paid trip to Estonia for IT specialists looking to move to the country.

The targeted approach to immigration, coupled with the fact that in the past decade Estonia has rebranded itself as the global leader in digitalization—spearheading concepts such as e-Residency, E-Estonia, and digital identification cards (government initiatives to simplify citizen and resident access to the Estonian government’s online services, thus allowing entrepreneurs to invest in and manage digital businesses from anywhere in the world)—has garnered results. According to the 2018 Eurobarometer, 66 percent of those surveyed judged the economic situation “good.” Also, since 2015 Estonia has managed to turn around its population decline, even if modestly; around 6,000 more people immigrated to the country than emigrated in 2018. However, the Estonian public has been less than thrilled by the idea of new immigration, even with the improving economic climate. Estonians have consistently ranked immigration as the main concern for the European Union in the Eurobarometer surveys. In the same survey, when asked about the main concerns at the national level, in comparison to the citizens of Latvia and Lithuania, immigration proved the highest concern for Estonians (albeit just 12 percent of the Estonian population listed it as the main concern facing the nation).

Lithuania Bets on Information Technology to Connect Diaspora

Lithuania, more so than its neighbors, actively uses information technology to encourage return migration. The country also makes information regarding its demographic situation open and accessible to the public. For example, its Migration in Numbers website hosts reliable statistical data on issues such as emigration, immigration, foreigners and asylum seekers, and the rate of return migration. This open approach may be paying off in terms of fostering understanding: according to survey data, Lithuanians are the most tolerant and accepting of immigrants among the Baltic countries.

In 2007, the Lithuanian government adopted the Economic Migration Regulation Strategy as a means to overcome the effects of emigration and to establish priorities, such as reducing emigration and encouraging return migration. After the 2009 global financial crisis—which spurred more emigration—in 2014 the Migration Policy Guidelines were implemented, which highlighted that migration flows are necessary for social and economic development. As a result, the amended Law on Legal Status of Aliens made immigration to Lithuania easier for third-country nationals (those coming from beyond the European Union). In 2018, further amendments allowed foreign graduates and researchers to extend the duration of their stay, and residence permit acquisition has been simplified for professionals in sectors of anticipated labor shortages, in accordance with the Employment Service of the Ministry of Social Security and Labor.

The foreseeable inflow of third-country nationals has also prompted the Lithuanian government to think about effective integration of newcomers. As of January 2019, the government had established a taskforce on integration, the Action Plan for Integration of Foreigners in Lithuanian Society 2018-20. Despite these policies, the rates of immigration to Lithuania, remain very low: in 2017, 9,513 third-country nationals immigrated to the country, most coming from Ukraine and Belarus.

Lithuania was an early adopter of diaspora engagement strategies and has worked actively to promote return migration. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Department of Lithuanians Living Abroad has coordinated the Global Lithuania diaspora program since 2011. The nongovernmental organization Global Lithuanian Leaders also engages with the diaspora: with a membership of 1,700 Lithuanian professionals based in 49 countries, the organization aims to contribute to the country's prosperity. Together, the official diaspora engagement policy and Global Lithuanian Leaders run various programs that encourage youth and professionals to return and work in Lithuania or share their acquired knowledge and expertise.

In addition, the government manages a website, called “I Choose Lithuania,” dedicated to promoting return migration. In recent years, the website has moved away from providing information only for returning diaspora members, to providing information to anyone interested in moving to Lithuania. As such, in 2017 Lithuania was able to attract 10,155 diaspora members, with almost half of those returning from the United Kingdom. However, in light of the rate of emigration—47,925 Lithuanians left the country in 2017—and the low rate of immigration of third-country nationals, Lithuania’s net migration rate remains the worst in the European Union. In the 2018 Eurobarometer survey, just 40 percent of Lithuanians described the economic situation as favorable, suggesting that emigration will continue to be a problem in the near future.

Latvia Focuses on Engaging Diaspora Instead of Encouraging Non-EU Migration

As of January 1, 2018, 74,840 third-country nationals legally resided in Latvia, less than 4 percent of the total population. Immigration of third-country nationals is regulated by the Immigration Law, which went into force in 2002 and has been incrementally amended almost every year. After the 2009 global financial crisis, Latvia established an investor visa program, allowing investors from outside the European Union to receive a residence permit in exchange for a certain level of investments. Most recently, the country has approved the start-up visa for individuals developing innovative products.

Last year, the Cabinet of Ministers approved a Migration Policy Conception, which would further amend the immigration law by focusing on attracting a skilled labor force, alleviating regulations for third-country nationals already employed in Latvia, and making it easier for non-EU students studying in Latvia to remain and seek employment after graduation. These recommendations have yet to be formally included. However, Latvia’s new government, which took office in 2019, does not seem to consider immigration as a priority, making only a fleeting mention of considering immigration reform to alleviate labor shortages in its government declaration. Immigration policy reform is not likely to be a principal focus of the new cabinet, and Latvia is still in the process of defining a strategy towards immigrants.

Instead, the newly implemented diaspora law, which went into force on January 1, 2019, suggests that Latvia is likely to further focus on engaging and working with its diaspora, which it has been doing since 2004 when the first Latvian Diaspora Support Program was introduced. The diaspora law, coordinated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, will create a systematic framework for further implementation of diaspora policy. Besides measures to foster the preservation of the Latvian language and culture abroad, the policy will support diaspora organizations, encourage return migration, and engage the diaspora in economic development. Most notably, the legislation is innovative in its definition of the Latvian diaspora, offering a very broad interpretation of who can self-identify—and be recognized—as part of the Latvian diaspora, including the so-called affinity diaspora: “citizens of Latvia permanently residing outside of Latvia, Latvians, and others who have a lasting social connection to Latvia, as well as their family members.”

Latvia is also a leader in the Baltic states in terms of facilitating diaspora engagement through dual citizenship. In 2013, Latvia amended its citizenship law permitting dual citizenship with EU and NATO Member States, Australia, Brazil, and New Zealand, thus allowing the descendants of Latvian emigrants to acquire Latvian citizenship in addition to their existing citizenship. Estonia does not recognize dual citizenship formally, and Lithuania is set to hold a referendum on the issue in 2019.

In terms of return migration, the Latvian government has been actively involved in facilitating return since 2018, when the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development launched a pilot program with the aim of assisting families abroad to return and settle. The program has five regional coordinators who can assist with such issues as employment opportunities, help finding housing, assisting with registering children for childcare and school, and even applications for financial support to start a business. Data from 2018 suggest that the program has wooed back 185 families, with a further 217 families expressing intent to return in the near future.

However, the rate of return migration, with or without state assistance, is nowhere near what it needs to be in order to compensate for anticipated labor shortages. According to Re:Baltica, 9,500 Latvian diaspora members would need to return each year. However, according to the data from the Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia, in 2017,14,622 Latvian citizens emigrated and just 4,780 returned. Thus, the rate of return migration and the small number of third-country nationals residing in Latvia suggest that the Latvian net migration rate remains decisively negative. Further complicating the situation is the fact that nearly 63 percent of those surveyed by the 2018 Eurobarometer described the economic situation of the country as “bad.”

Challenges in Social Cohesion and Popular Attitudes about Immigrants

Of the Baltic states, only Estonia has been able to achieve a positive rate of net migration and accomplish a very modest population growth of 0.2 percent. The rebranding of Estonia as the digital republic—and efforts to make information about living and working in the country available to all interested—seem to be working. Contributing to the Estonian success is the fact that the population appears to be satisfied with the economic situation. However, in light of the looming UN population predictions for 2050 and trends in aging, this should not make the Estonian government feel too comfortable. Further efforts to promote immigration will be necessary in order for Estonia to maintain its population. At the same time, there is a worrying trend in popular opinion regarding the negative perception of immigration.

Latvia and Lithuania have implemented a more targeted diaspora engagement strategy, and have seen a slight increase in return migration of their diasporas; however, this can be partially attributed to the uncertain situation in the United Kingdom, where the number of workers from Eastern European countries has been continuously declining amid the Brexit confusion. Return migration is still nowhere near the rate it needs to be in order to overcome the challenges in economic growth and labor shortages, as cautioned by the World Bank and IMF. The salary disparity between the Baltic countries and Western Europe, as well as the unfavorable popular perception about the economic situation of the countries, makes it highly unlikely that return migration will significantly increase or that immigration can be expected from within the European Union. Thus, Latvia and Lithuania will have to think of ways to attract third-country nationals to fill the employment vacancies and increase contributions to the state budgets.

In order to become more attractive immigration destinations, Estonia—and to some extent Lithuania—have altered their specific return migration initiatives to be more friendly and accessible to foreigners interested in information about work and residence. Latvia, on the other hand, seems to be ignoring the impending demographic crisis, with no clear signs from the new government that immigration will become a top issue of concern. In fact, Latvia still lacks an easily accessible information platform that promotes the country’s opportunities, the prospects of return, or the benefits for third-country nationals who migrate there.

The popular attitudes towards immigrants from countries outside of the European Union continue to be a problem for the Baltic states. Estonia, which currently has the highest rate of immigration of third-country nationals, also registered the highest level of public concern about immigration. In Latvia, 41 percent considered non-EU migration more of a problem than an opportunity, according to the 2017 Eurobarometer survey. The same survey also registers the popular opinion regarding the success rate of integration policy. Not surprisingly, Latvians and Estonians, 45 percent and 53 percent respectively, claim that integration efforts of immigrants are not successful in their respective countries. Thus, the Baltics not only have a demographic challenge on their hands, but also unresolved issues surrounding integration and social cohesion, which will continue to pose serious challenges for the future of immigration policy.

Sources

Annus, Ruth. 2018. Developments in Estonian Migration Policy. Presentation at Nordic-Baltic Migration Conference 2018, Tallinn, March 22, 2018. Available online.

Antoneko, Oxana. 2017. Refugees Frustrated and Trapped in Chilly Baltic States. BBC News, July 4, 2017. Available online.

Atoyan, Ruben et al. 2016. Emigration and Its Economic Impact on Eastern Europe. Staff Discussion Note, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, July 2016. Available online.

Bodewig, Christian. 2015. Is the Refugee Crisis an Opportunity for an Aging Europe? Brookings Institution blog post, September 21, 2015. Available online.

Cabinet of Ministers of Latvia. 2004. Par Latviešu diasporas atbalsta programmu 2004.-2009.gadam (Latvian Diaspora Support Program 2004-09). Order No. 738. October 5, 2004. Available online.

---. 2011.Nacionālās identitātes, pilsoniskās sabiedrības un integrācijas politikas pamatnostādnes 2012.–2018.gadam (National Identities, Civil Society, and Integration Policies 2012-18). Order No. 542. Available online.

---. 2013. Par Reemigrācijas atbalsta pasākumu plānu 2013.-2016.gadam (Return Migration Support Action Plan 2013-16). Order No. 356. July 30, 2013. Available online.

---. 2018. The Government Supports the Conceptual Report on Immigration Policy. Press release, February 13, 2018. Available online.

---. 2019. Latvia’s New Prime Minister Announces His Cabinet. Press release, January 23, 2019. Available online.

Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. N.d. Distribution of International Long-Term Migrants by Citizenship of Migrants—IBG043. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

---. N.d. International Long-Term Migration by Country Group—IBG020. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

---. N.d. Migration Data. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

---. N.d. Refugees Latvia. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

Economist. 2018. Europeans Remain Welcoming to Immigrants. The Economist, April 19, 2018. Available online.

ERR News. 2017. Report: Estonia Unable to Maintain Population Size without Immigration. ERR News, June 1, 2017. Available online.

Estonian Research Council. N.d. Returning Researcher Grants. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

European Commission. 2015. Refugee Crisis: European Commission Takes Decisive Action. Press release, September 9, 2015. Available online.

---. 2018. Public Opinion in the European Union. Standard Eurobarometer 90, Autumn 2018. Available online.

---. N.d. Governance of Migrant Integration in Latvia. Updated March 15, 2019. Available online.

---. 2019. New Immigration and Integration Regulations Now in Force in Lithuania. Press release, January 11, 2019. Available online.

European Migration Network. 2016. About Us: Lithuania. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

---. 2018. Foreign-Born Population by Country of Birth. Accessed May 6, 2019. Available online.

Eurostat. 2019. Minimum Wages in the EU Member States Ranged from EUR 286 to EUR 2,071 per Month in January 2019. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

Global Lithuanian Leaders. N.d. Global Lithuanian Leaders. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

Heller, Nathan. 2017. Estonia, the Digital Republic. The New Yorker, December 18, 2017. Available online.

Integration Foundation. N.d. Return Support Estonia. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2018. IMF Staff Concludes Visit to Latvia. Press release, January 23, 2018. Accessed 04.25.2019. Available online.

---. 2018. IMF Staff Concludes Visit to the Republic of Lithuania. Press release, October 29, 2018. Available online.

Kumer-Haukanõmm, Kaja and KeiuTelve. 2017. Estonians in the World. In Estonia at the Age of Migration, eds.TiitTammaru, KrisitnaKallas, and Raul Eamets. Tallinn: Estonian Human Development Report 2016-17. Available online.

Lithuanian Legislative Register. 2018.On the List of Professions Lacking Employees in the Republic of Lithuania by Kind of Economic Activity in 2019. Order No. V-628. December 19, 2018. Available online.

Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX). 2015. Overall Score, 2014. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

Ministry for Environmental Protection and Regional Development. N.d. About Regional Remigration Coordinator Project (PAPS). Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania. 2014. About Us. Updated March 23, 2016. Available online.

Muižnieks, Nils, Juris Rozenvalds, and Ieva Birka. 2013. Ethnicity and Social Cohesion in the Post-Soviet Baltic States. Patterns of Prejudice 47 (3): 288-308.

Päevaleht, Esti. 2011. Expats Reluctant to Return. VoxEurop, April 21, 2011. Available online.

Puriņa, Evita. 2017. Why Return of Expats Is False Hope for Latvia’s Labor Problems. Re:Baltica, October 18, 2017. Available online.

Ragozin, Leonid. 2018. Europe’s Depopulation Time Bomb Is Ticking in the Baltics. Bloomberg, April 20, 2018. Available online.

Raphael, Therese. 2019. Europeans Are Leaving Britain (Poorer). Bloomberg, March 4, 2019. Available online.

Republic of Estonia Ministry of Education and Research. N.d. Compatriots Programme. Updated October 23, 2018. Available online.

Republic of Latvia. 1994. Citizenship Law. July 22, 1994. Available online.

---. 2002. Immigration Law. October 31, 2002. Available online.

---. 2010. Regulations Regarding Residence Permits. June 21, 2010. Available online.

Republic of Latvia Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs. N.d. Residence Permit Statistics 2018. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

RenkuosiLietuvą. N.d. RenkuosiLietuvą (I Choose Lithuania). Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

Spriņģe, Inga. 2017. A Country for Old Men. Re:Baltica, September 21, 2017. Available online.

Startup Estonia. N.d. About Startup Estonia. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

Statistics Estonia. 2019. The Population of Estonia Increased Last Year. Press release, January 16, 2019. Available online.

Statistics Lithuania. 2014. Lithuanians in the World. Updated December 12, 2014. Available online.

Tammaru, Tiit, Krisitna Kallas, and Raul Eamets, eds. 2017. Estonia at the Age of Migration. Tallinn: Estonian Human Development Report 2016-17. Available online.

United Nations Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2017.World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision. Updated June 2017. Available online.

Work in Estonia. N.d. Work in Estonia. Accessed April 25, 2019. Available online.

World Bank. 2015. The Active Aging Challenge: for Longer Working Lives in Latvia. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Available online.