You are here

China’s Rapid Development Has Transformed Its Migration Trends

Man in front of China Import and Export Fair in Guangzhou, China. (Photo: iStock.com/Plavevski)

As China has developed into a global power, it has also increasingly become a nation of people on the move. In 2019, the 350 million border crossings by mainland citizens and 98 million by foreign nationals again reached record highs, continuing a decades-long upward climb interrupted only by China’s strict border-control measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The increase in migration to and from the country is deeply intertwined with its history of socioeconomic reforms. After China’s leaders in 1979 identified global economic integration as a key target, many of its citizens moved abroad in search of better economic opportunities. Previous decades had been marked by the state’s control of international movement, but global mobility gradually became more accessible in the late 20th century and the new millennium.

The story of China’s mobility boom starts at home, with millions of internal migrants moving from the country’s rural interior to the coastal areas, where they have contributed to the country’s urbanization and export-driven manufacturing growth. China officially became an aging nation in 2000, and the working-age population has peaked; in 2020, about 19 percent of its 1.4 billion citizens were over 60, the retirement age. Yet the scale of China’s internal migration remains unmatched: in the 2020 census, nearly 376 million people lived someplace other than their household registration area, a group often referred to as the “floating population.”

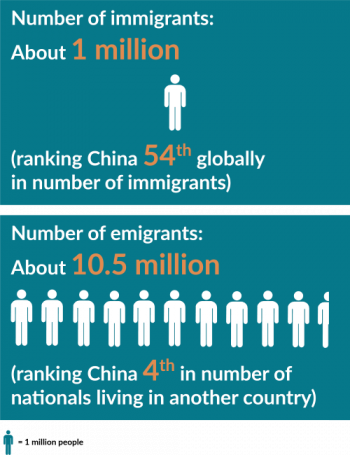

China experienced an “emigration craze” after the 1990s, during which millions of people moved abroad. An estimated 10.5 million Chinese citizens lived abroad as of 2020, according to United Nations estimates. The Chinese government has sought to maintain ties with these “new” migrants, as they are called to differentiate from those who emigrated in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and has in recent years also emphasized linkages with the wider diaspora, which has been estimated at between 35 million and 50 million.

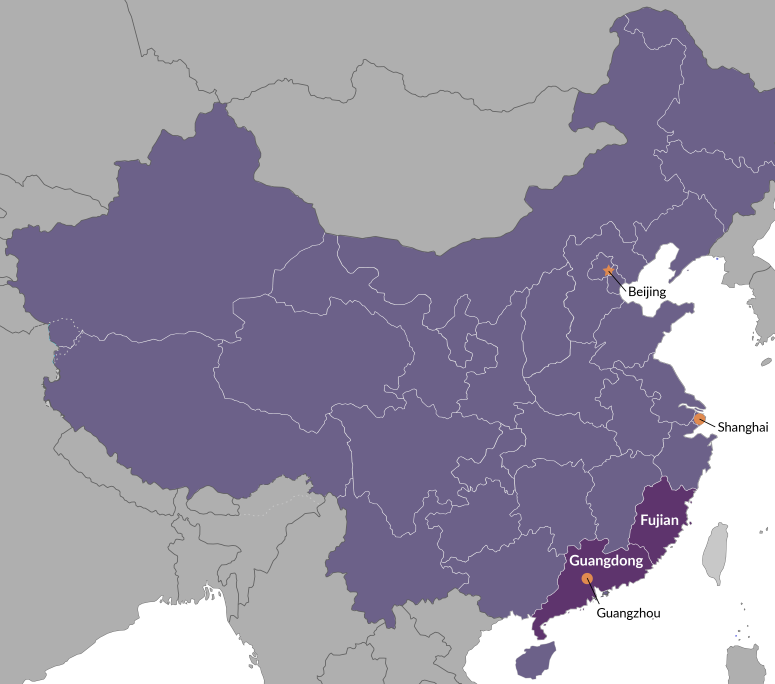

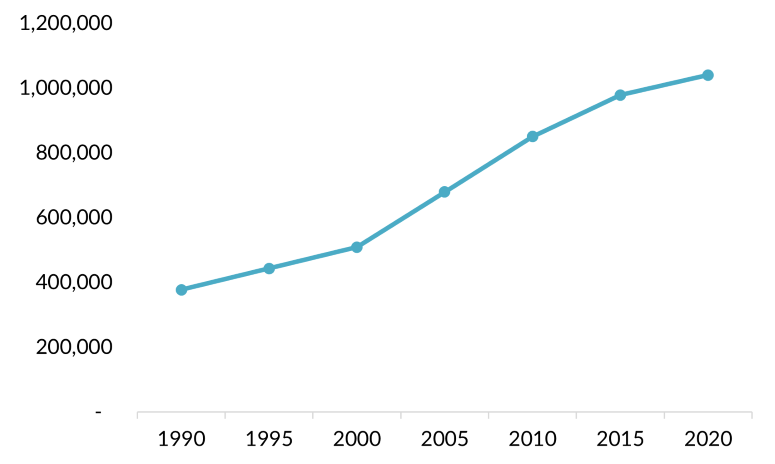

As China’s development took off, the country also has attracted growing numbers of foreign-born migrants and has emerged as an immigrant destination country, particularly following its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. South Korea, the United States, and Japan are key migrant source countries, but China’s position as an economic hub increasingly attracts migrants from around the globe, including traders and students from the global South. The 2020 census counted 1.4 million overseas residents (jingwai renyuan) in mainland China—which is sizable in absolute terms but accounts for just 0.1 percent of the total population—including 846,000 foreign nationals and 585,000 residents of Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan, although these are underestimates that fail to capture people in irregular status. Almost one-third of these immigrants live in the southern province of Guangdong, the manufacturing powerhouse where Deng Xiaoping launched China’s economic reforms policies.

In this post-1979 reform era, the government has managed migration by focusing on supporting China’s development. Still, international mobility has retained an ambiguous position in the nation-building project, which has been defined around China’s self-sufficiency. The strict border-control measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic were illustrative of this tension. Because of lingering political sensitivity around international mobility, legal and institutional frameworks for managing migration have lagged. For immigrants and returning migrants, there has been a narrow focus on migration’s economic benefits, while broader questions of integration and societal diversity remain unaddressed. Pathways for permanent residence remain extremely limited. Despite China’s looming demographic crisis, there is also little long-term planning for future immigration that might be needed to offset consequences of population aging.

This article discusses trends in China’s international mobility, particularly amid the economic reforms of the last four decades. Throughout the history of the People’s Republic of China, migration has been managed for selective developmental aims and often in service of broader geopolitical goals. After 1949, controlling migration was a key concern for the Chinese government. With the post-1979 reform policies, China developed from a country of limited migration into one in many ways defined through its global interactions, although it continues to treat migration warily. While the country has become older, more urbanized, and wealthier, it struggles to rebalance economic needs and political considerations.

“Old” Migration (pre-1949): Crossing Borders to Escape Poverty and Strengthen the Nation

China experienced significant emigration in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Twenty million Chinese moved to Southeast Asia between the 1840s and the 1920s, building on centuries of regional trading routes; many also went to destinations around the globe, including the Americas. The vast majority of Chinese emigrants were male and came from the southern provinces of Guangdong and Fujian. They often went abroad as temporary sojourners rather than permanent settlers. However, about 40 percent never returned to China.

Chinese emigration in this era had significant impacts on international politics. Chinese arrivals to the United States led to the first major immigration restriction law in that country’s history, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and other anti-Chinese and anti-Asian efforts occurred in countries such as Australia and Canada. In China, interest in protecting its citizens abroad—particularly labor migrants in the Americas—led to a recognition of the importance of diaspora politics and resulted in China’s first overseas diplomatic missions.

At the same time, immigration to China increased rapidly in the 19th century, following a series of military defeats to Western powers and Japan, during a period known as the “century of humiliation.” Settlers came as traders, investors, missionaries, and educators of Euro-American, Japanese, and Russian origin, leading to a semi-colonial society in parts of coastal and northern China. A period of significant Chinese-foreign exchange under unequal conditions followed, with foreign nationals largely falling outside Chinese jurisdiction. In 1942, more than 150,000 foreign nationals lived in Shanghai’s foreign concessions, which operated independently of Chinese sovereignty. This was a high-water mark that would not be reached again in the metropolis until 2008.

Figure 1. Map of the People’s Republic of China

Source: MPI artist rendering.

Note: Dotted lines represent disputed territories. Map is for illustrative purposes and does not indicate endorsement or support for territorial boundaries.

Mobility into and out of China became tied up with its nation-building ambitions, and popular and at times violent resistance to immigrants was widespread by the early 20th century. During the same period, China’s first generations of foreign-bound students went to Europe, Japan, and the United States with the aim of learning and returning to modernize their homeland. Upon return, many of these students went on to play leadership roles in China’s nationalist movements and later the Chinese Communist Party.

Post-Liberation (1949-79): Containing Migration to Safeguard the Revolution

The founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 followed prolonged war and poverty-driven population displacement, leading the new government to make a top priority of controlling migration. Party Chairman Mao Zedong considered “cleaning the house” of foreign influence crucial to reckon with China’s history of imperialist aggression, and the foreign-born population dropped sharply in the 1950s. International arrivals and departures fell even lower in the late 1960s, when foreign ties became highly politicized during the Cultural Revolution. Emigration was similarly difficult, as the government limited the issuance of passports and exit permits, among other measures. Internally, China turned to a household registration system (hukou) built upon a long legacy of regulating movement, which aimed to prevent unapproved internal migration and enforce a developmental model in which rural agricultural production supported urban industrialization.

These first years of the People’s Republic of China are sometimes called the “static decades” due to government control over mobility, but migration was not completely halted. In the 1950s, migration of technical experts and highly skilled individuals to and from the Soviet Union supported industrial development. As South-South cooperation became more important for its diplomacy, China dispatched laborers to work on development projects in Africa and Asia. Refugees also left during periods of famine and political hardship, mostly to Hong Kong. China meanwhile continued to receive diplomatic delegations and even tourists from countries with which it was aligned, although the largest arrivals came from returning Chinese migrants and their descendants in Indonesia and Vietnam. Internally, millions moved to China’s peripheral regions, encouraged by state policies or as part of political campaigns.

Migration management in this period was characterized by strong ideological concerns and limited immigration governance experience. Ethnic Chinese return migrants and new arrivals from the diaspora were settled on state-owned farms without paths to full integration, leading to citizenship issues that lasted for generations. The state imported a Soviet-style system for international visitors aimed at hosting and controlling so-called “foreign friends.” This system was later expanded and adapted to the reform-era purposes of attracting foreign investment and technology while minimizing foreign interference. Chinese citizens were educated in how to engage foreigners while minimizing in-depth contact.

The First Two Decades of Reforms (1979-90s): Resumption and Acceleration of Migration

Internal and international migration became a means of economic rather than political mobilization in the reform era. China’s economic reforms reduced state ownership, unleashed market forces, and expanded manufacturing in China’s coastal zones, generating demand for labor largely filled by migrant workers from the countryside. Controls on international mobility were meanwhile gradually relaxed, while diplomatic relations with many countries normalized.

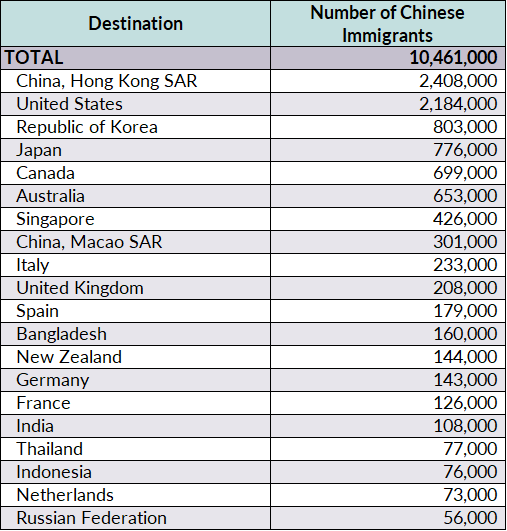

Table 1. Top Destinations of Settlement for Chinese Migrants, 2020

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Population Division, “International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin, Table 1: International Migrant Stock at Mid-Year by Sex and by Region, Country or Area of Destination and Origin,” accessed January 22, 2022, available online.

As it became possible for more citizens to obtain passports, emigration increased and diversified. China dispatched contract laborers abroad through government agencies at the request of countries with labor shortages, bringing sorely needed foreign currency to China. Other migrants left on their own to join relatives abroad. In the early 1990s, the largest ethnic Chinese populations outside China were in East and Southeast Asia, but the highest growth of Chinese migrants was in North America, Western Europe, Japan, and Australia. Many of these migrants hailed from traditional emigration areas in southern China.

Although opportunities expanded, many people remained ineligible to leave China through regular channels. Unmet migration aspirations laid the foundation for a smuggling industry involving transnational networks of Chinese brokers who sometimes demanded steep fees or forced service. However, intense Western media attention on human smuggling from China was arguably disproportionate to the problem’s scale.

Encouraging citizens to travel abroad was not only a source of foreign currency for China, but also a way to catch up with global developments in science and technology. During the first 20 years of reform policies, some 320,000 students went overseas. About half of these went on government scholarships or through employment, with the rest self-funded. However, access to international education often led students to settle abroad permanently. Only about one-third of these students returned to China. In addition, a wave of activist students, workers, and intellectuals fled to the United States and Europe in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square rallies.

In addition to encouraging Chinese youth to study abroad, the country also attracted migrants to support its economic development. The region surrounding mainland China—Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea—developed economically through export-oriented manufacturing, but saw costs rise from the 1980s onwards. China’s coastal regions offered these foreign companies cheap labor and land. Foreign-born managers and technicians, many of them members of the Chinese diaspora, moved to China to set up production. The development of infrastructure catering to foreigners, including international schools, encouraged migrants to bring their families. By the late 1990s, large Chinese cities offered globally mobile professionals a living standard similar to that of cosmopolitan areas around the world.

The New Millennium (2000-Present): Explosive Growth and Diversification of Migration

As China’s economic development flourished after 2000, international migration both into and out of the country increased. The country’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization boosted its export-led manufacturing and the domestic demand for labor. Strict family planning policies from the 1980s onwards lowered birth rates, and fewer children meant smaller groups of workers entering the labor force. The arsenal of rural-born workers shrank and growth in rural-urban migration abated. However, labor shortages did not drive the surge in international migration to China in this period, and little precedent or regulation exists for the immigration of unskilled workers. Instead, increased immigration was a result of new professional, commercial, and educational opportunities in China.

Figure 2. Number of Immigrants in the People’s Republic of China, 1990-2020

Source: United Nations DESA, Population Division, “International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin, Table 1: International Migrant Stock at Mid-Year by Sex and by Region, Country or Area of Destination and Origin,” accessed January 22, 2022.

Diversification of Immigrant Settlement and Emigration

Recent immigrants originate from diverse countries of origin. Although Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Beijing remain major destinations, more immigrants now also settle in Chinese second-tier cities. Several dynamics have promoted this geographic dispersal, including the arrival of ethnically Chinese people with ancestral connections to various areas and efforts to attract foreign students by higher education institutions outside major cities advertising lower costs. Economic development throughout the country has also produced professional opportunities in more regions, and the growth of transnational families has brought many foreign-born partners to their spouses’ places of origins. Finally, increased economic integration along China’s land frontiers has driven an increase in cross-border migration.

Guangdong province has a larger and more diverse foreign-born population than anywhere else in China. In addition to the foreign experts and investors mentioned above, traders from Africa, South Asia, and the rest of the world have a very visible presence in some neighborhoods. Some immigrants travel back and forth to their countries of origin or attempt to use China as a transit destination en route to wealthier countries.

The backlash against irregular migration has been particularly strong in Guangdong, where African immigrants have been conflated with unauthorized migrants, of which there is a sizeable group in the region. Individuals who enter, reside, or work in China without proper documentation are dubbed as “three illegals” (san fei) and over the past two decades they have been targeted as a source of social instability.

Anti-san fei campaigns take place beyond Guangdong and take on different expressions depending on the immigrant group and local context. For instance, marriages between Chinese and Vietnamese citizens have come under public scrutiny due to the role of marriage brokers and, at times, trafficking. Individuals on tourist and student visas working informally as English teachers went from being welcomed by local authorities to prosecuted for illegal employment and other offenses.

Migration out of China has also become larger and more diverse. The percentage of Chinese citizens with a passport increased from around 2 percent of the population in 2010 to nearly 15 percent, or more than 200 million people, in 2019 (compared to 47 percent in the United States). As in the 1980s, Chinese nationals often move to Europe and North America for work and family reunification, however this mobility has decreased relative to other migration streams such as foreign study. In 2016, the number of Chinese students entering Europe surpassed those entering on work and family reunification visas. More than 700,000 Chinese higher education students went abroad in 2019, and about 500,000 international students attended higher education in China in 2018. In a new trend, so-called lifestyle migrants have also gone to Europe and elsewhere in Asia in search of warmer weather and a better quality of life.

Many of these trends were put to the test during the COVID-19 outbreak. China set up especially stringent pandemic border restrictions as part of its “zero-COVID” strategy, bringing movement to and from the country to a near halt over 2020 and 2021. In the first half of 2021, border crossings stood at 10 percent of 2019 levels, with no indications of borders reopening as of this writing. However, although international observers worry about China’s self-isolation, there is little evidence that authorities intend to maintain severely reduced international mobility beyond its purpose as a public-health strategy.

Several years of disruption cannot undo decades of cross-border exchange, but pandemic-era restrictions are certain to have a major impact on all mobility streams into and out of China. Two years into the pandemic, Chinese students still traveled abroad in great numbers, but China’s attractiveness as a study-abroad destination declined as foreign students were barred from entry. Travel restrictions made it difficult and expensive for Chinese citizens working abroad to return and for members of transnational families to meet. In short, during the years of the pandemic, living between China and other countries became difficult, and the border closure experiences may affect how people organize their lives even once lifted.

More Immigrants, but Lagging Systems to Regulate and Integrate Them

Although China’s migrant populations have grown, the legal and institutional framework for managing them has lagged. Policy has focused on attracting top professionals, return migrants, and foreign students, but a more robust system expanding migrant rights and encompassing lower-skilled workers and others has been slow to materialize, due to political sensitivities and a notoriously fragmented and opaque bureaucracy that has been dominated by security authorities.

China’s central immigration law, the 2012 Exit-Entry Administration Law, was developed through multiple drafts over a decade. With sections on national security and irregular migration, the law strengthened the government’s control over immigration but was largely silent on migrant rights and integration. A system by which immigrants could obtain permanent residence was introduced in 2004, but has been implemented on a case-by-case basis. Only around 10,000 individuals received this status between 2004 and 2016. Naturalization figures are even lower.

However, enforcement has often been lenient in recent decades, as authorities have focused on how cross-border flows might aid China’s development. In line with the overall development focus, border regions and urban areas with high concentrations of immigrants have often developed local legislation and practices for managing migration. Such local-level accommodation can shift when immigrant groups become a political liability, most notably for African trader communities in Guangzhou. The city responded by selectively increasing immigration enforcement; this marginalized many Africans, and their numbers subsequently dwindled, from an estimated 80,000 registered African migrants in 2005 to 13,652 in December 2019.

Recent Developments Suggest New Focus on Migration Governance

Reform has sped up since Xi Jinping became head of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012 and initiated a wave of governance reforms. In 2016, China joined the International Organization for Migration. An example of the policy evolution is the 2017 foreigner working regulations, which provide more detailed categories for economic migration and have significantly reduced the role of individual officers’ discretion in issuing visas.

In 2018 Beijing undertook two reforms indicating that international mobility has risen on the central leadership’s policy agenda. The government established the country’s first national migration agency, the National Immigration Administration (NIA), responsible for both arrivals and departures. The NIA is charged with coordinating migration affairs government-wide, although its relatively low bureaucratic status makes this mandate difficult to fulfill. The NIA’s initial focus has been on building a more comprehensive immigration system for the groups authorities want to attract, for the first time considering issues of social integration, and strengthening border control capacity. At the same time, the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office, which is responsible for diaspora affairs, was moved to a key Chinese Communist Party department.

Still, China’s immigration framework remains incomplete, and is often ill suited to the realities of recent de facto permanent immigration, with many migrants settling in China without ever gaining full residency rights. Its visa categories are restrictive, with migrants on spousal or student visas unable to work. And immigrants lack robust labor rights. The rigidity of the system also became apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic when entry to the country became limited to Chinese nationals and the few immigrants who hold permanent residency.

Ongoing Themes in Chinese Migration Policy

As international mobility has grown and diversified, China’s limited and predominantly economy-focused framework has been increasingly challenged. This shift is reflected in current policy issues.

International Mobility and China’s Growing Global Role

China’s footprint abroad is larger than ever. Emigrants have helped Chinese capital “go out” (zou chuqu) into a range of industries worldwide, including agriculture, mining, and retail. Since 2013, its investment has been boosted by the Belt and Road Initiative; backed by government financing, state-owned enterprises and companies have built ports, power stations, roads, skyscrapers, and other buildings around the world.

Investments are particularly intense in Africa, where official sources report there were nearly 183,000 Chinese workers in 2019 (precise data are lacking, but the total number of Chinese migrants in Africa is commonly estimated to be around 1 million), many of them working as project managers and technicians. Some are also low-skilled Chinese workers, although their presence depends on local labor and immigration laws and enforcement practices. Chinese workers in jobs that could have gone to locals are controversial in many developing countries, with the situation at times sparking diplomatic tensions.

As Chinese migrant workers spread out to more countries, including conflict zones, the Chinese government has come under pressure to protect them. The 2011 evacuation of 37,000 Chinese nationals from Libya was a turning point in China’s state response on this issue. The deployment of military assets to support the evacuation was a display of Chinese capacity to protect its citizens overseas. While the limits to China’s willingness to care for dispatched citizens have been tested by the COVID-19 induced travel bans and high threshold for return, the prioritization of overseas workers when Chinese vaccines were first developed reconfirmed its commitment to protect its emigrants.

China’s Demographic Transition

China has long defined itself by its large population, so its shrinking labor supply and rapidly aging society are key policy concerns. By 2030, more than one-quarter of China’s population is projected to be over 60 years old. However, there is little policy debate on filling labor shortages by recruiting more foreign workers, who generally need to have higher education and work experience to qualify for a work permit. The government has instead concentrated on mobilizing domestic labor and upgrading technology.

Still, the last decade has seen as many as several hundred thousand unskilled migrant workers in irregular status working in factories and other sectors (estimates are imprecise). In underdeveloped border regions where labor shortages have been acute, there have been local policy efforts to regularize foreign migrants working in these areas.

Recent years have also seen a rise of foreign-born spouses moving to China, highlighting a gender imbalance that is largely a product of years of family-planning policies and associated gender-selective abortions. Rural and poor men can have a difficult time finding suitable Chinese partners, creating a demand for wives from Southeast Asia and, to a lesser extent, Russia, which in turn has led to trafficking of women. The problem of cross-border trafficking in women for marriage has been a key issue in China’s cooperation with international migration organizations. The gender imbalance and marriage-related expenses are also a major driver for men to work abroad.

Return Migration and Competition for Talent

The Xi Jinping administration has further prioritized the return of Chinese emigrants with foreign degrees, dubbed “sea turtles” (haigui), in a Chinese pun on “return” (haigui), as well as students and professionals of Chinese descent. Since the early 2000s, the Chinese government has invested sizable resources to woo Chinese-born graduates in finance, science, and technology to limit brain drain. This became easier after the 2008 financial crisis, when tighter job markets in Europe and North America made China’s professional opportunities relatively more attractive for many. Return rates of Chinese students abroad have consistently increased since then, with around 80 percent returning between 2016 and 2019. The government’s focus has shifted to strengthening its position in the global competition for talent, such as by increasing incentives to attract top researchers of Chinese and other backgrounds through so-called talent programs, offering tax breaks, extensive research funds, and expedited access to multiple-year residence permits.

Additionally, diaspora policy now stresses that Chinese nationals can serve the country’s interest wherever they are. In 2013, Xi expressed the hope that overseas students could be “grassroots ambassadors” for China’s national interests whether they return to the country or not.

Yet Chinese emigrants and members of the diaspora have also been ensnared in intensifying geopolitical competition between China and other major powers. Since 2018, the U.S. government has investigated Chinese links of U.S.-based researchers, especially those with Chinese backgrounds. In turn, foreign nationals in China have on several occasions been detained as part of geopolitical disputes, or are subjected to exit bans on vague legal basis. These trends may discourage some Chinese emigrants, members of the diaspora, and immigrants in China from moving as freely.

Public Immigration Debate as a Growing Policy Factor

Immigration had been a relatively marginal societal concern in China, but in recent years it has attracted the attention of ethno-nationalists with links to global right-wing networks. Xenophobic views dominate online discussions on immigration, yet remain in the minority overall. Surveys show that anti-immigration sentiments became more pronounced in the 2010s compared to the previous decade, but most Chinese citizens nonetheless support maintaining or increasing immigration.

However, some issues have resonated among portions of the Chinese public wary of immigration, who in some cases have demanded firmer, more selective policies. A 2020 draft law that would have expanded permanent residency rights for high-income immigrants stirred up a torrent of criticism, much of it around the impact of increased immigration on Chinese society and policies such as scholarships for foreign students and tax breaks for foreign-born professionals. In an example of how public controversy around immigration can influence stability-oriented Chinese policymakers, authorities responded by swiftly shelving the law. For the same reason, media censorship of some migration-related topics has also increased in recent years.

Looking Ahead: Balancing Evolving Pressures

As China solidifies its position as a global superpower, its migration trends and governance are evolving. The interruption of the COVID-19 pandemic will have a significant short to middle-term impact on mobility flows to and from China as well. But some longer-term trends can be discerned. Improving domestic economic opportunities may lead to a plateauing of some types of emigration, such as student migration. Chinese emigrants increasingly see their time abroad as a temporary phase before the next stage of life back in China. In addition, overall outward mobility will likely continue to grow as more Chinese nationals are able to afford international travel.

For decades, the country has taken a pragmatic, developmentalist approach which largely put off long-term planning for its growing foreign and transnational populations. But immigration management has risen on the policy agenda, driven by changes in Chinese leaders’ aspirations and increased state capacity. Authorities aim to gradually build a more comprehensive immigration system by closing loopholes and increasing controls, while also keeping permanent immigration limited. This rebalancing of development and security concerns is likely here to stay. Meanwhile, public attitudes towards immigration are also undergoing change, and the issue might well become more salient and polarizing.

Finally, it remains unclear to what extent China will embrace foreign workers to mitigate looming domestic demographic challenges. Replacing the shortfalls of low birthrates with immigrants would require a major change in the public conception of the Chinese nation, which has often been defined in ethnic terms. However, given the twists and turns in international mobility to and from the country over the last century, pragmatic shifts remain possible.

Sources

Bickers, Robert. 2011. The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire, 1832-1914. New York: Penguin Global.

Brady, Anne-Marie. 2003. Making the Foreign Serve China: Managing Foreigners in the People's Republic. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Cheuk, Ka-Kin. 2019. Transient Migrants at the Crossroads of China’s Global Future. Transitions: Journal of Transient Migration 3 (1): 3-14.

Haugen, Heidi Østbø. 2012. Nigerians in China: A Second State of Immobility. International Migration 50 (2): 65-80.

---. 2015. Destination China: The Country Adjusts to its New Migration Reality. Migration Information Source, March 4, 2015. Available online.

Ho, Elaine Lynn-Ee. 2018. Citizens in Motion: Emigration, Immigration, and Re-Migration Across China's Borders. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Lan, Shanshan. 2017. Mapping the New African Diaspora in China: Race and the Cultural Politics of Belonging. New York: Routledge.

Liu, Guofu. 2011. Chinese Immigration Law. Burlington, VT: Routledge.

Liu, Hong and Els van Dongen. 2016. China’s Diaspora Policies as a New Mode of Transnational Governance. Journal of Contemporary China 25 (102): 805-21. Available online.

Liu, Jiaqi M. 2021. From “Sea Turtles” to “Grassroots Ambassadors”: The Chinese Politics of Outbound Student Migration. International Migration Review: 01979183211046572.

Lehmann, Angela and Pauline Leonard, eds. 2019. Destination China: Immigration to China in the Post-Reform Era. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ma, Yingyi. 2020. Ambitious and Anxious: How Chinese College Students Succeed and Struggle in American Higher Education. New York: Columbia University Press.

Nyíri, Pál. 2010. Mobility and Cultural Authority in Contemporary China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Pieke, Frank N. 2012. Immigrant China. Modern China 38 (1): 40-77.

Pieke, Frank N., Pál Nyíri, Mette Thunø, and Antonella Ceccagno. 2004. Transnational Chinese: Fujianese Migrants in Europe. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Speelman, Tabitha. 2020. Establishing the National Immigration Administration: Change and Continuity in China’s Immigration Reforms. China Perspectives 4: 7-16.

---. 2020. Chinese Attitudes Toward Immigrants: Emerging, Divided Views. The Diplomat, December 21, 2020. Available online.

Wang, Gungwu. 1979. The Chinese Overseas. Leiden, Netherlands: H. Champion.

Xiang, Biao. 2011. A Ritual Economy of ‘Talent’: China and Overseas Chinese Professionals. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (5): 821-38.