China: An Emerging Destination for Economic Migration

Editor's Note: The data in this article regarding Chinese immigration to Australia, Canada, and the United States have been updated. 1/9/2012

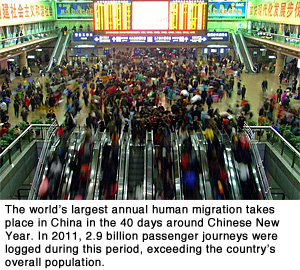

In the past few decades, China has undergone enormous political, economic, and demographic changes that have transformed the realities of migration to and from the country. In addition to large flows of emigrants leaving in search of opportunities elsewhere and the persisting, more traditional streams of internal migrants for which China is known, a new trend of immigration to the fast-developing country is emerging.

The driving force behind the recent trend of immigration to China — the world's most populous nation — has been the country’s rapid economic growth, compounded by its passage through a demographic transition. The growth of the Chinese labor force is slowing drastically at a time of mounting demand for labor, and this fact has increased pressure on wages and the country’s aging population.

The full impact of these demographic and economic changes on immigration remains to be seen. It is too early to see any evidence of an emerging "turnaround" in which net emigration gives way to net immigration; a trend seen in other rapidly growing economies in East Asia.

As China begins the necessary process of establishing an immigration policy to deal with its new status as a destination country, it also continues to be one of the great sources of the world’s migrants. China is ranked by the World Bank as the fourth largest country of emigration in the world, with 8.3 million China-born people living outside its borders in 2010. This figure includes some 3 million people born in China and living in Hong Kong and Macao, but China would still be considered a major country of emigration even if they were excluded as internal (rather than international) migrants.

Moreover, it was estimated that there were some 33 million ethnic Chinese living outside China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong toward the end of the 20th century. Large though this figure might appear, it is small compared with the total population of China itself, representing only 2.5 percent of a populace that presently nears 1.34 billion.

Any simple correlation, however, between the total population of China and the number of Chinese overseas is deceptive, because the majority of the latter trace their roots to a select few regions within China. The three southern coastal provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, and Zhejiang have dominated as sources of emigration, as have a limited number of districts, and even villages, within those provinces.

Historically, these areas were marginal to the Chinese state and weak in terms of their resource base. Most importantly, these areas were the earliest and most intensively affected by the seaborne expansion of European colonial powers, which linked them to a wider global system.

Furthermore, in contrasting the number of Chinese overseas with the base population of China, Chinese ethnicity must not be confused with Chinese migration, because many of the Chinese overseas were born outside of China in the lands chosen by their parents and grandparents.

China’s New Era of Immigration

Until the 1960s, China was characterized by high fertility that generated a "surplus" population that was available to migrate from certain parts of the country within the Chinese territory (especially to Taiwan and Hong Kong) and to various countries in Southeast Asia. This was followed by a period from the mid-1960s — and especially after the economic reforms of 1979 — of economic migration of skilled or educated Chinese to the Western states of North America, Europe, and Australasia.

Today, however, the situation is somewhat changed. While China is still the source of a large number of the world’s migrants, a new trend of immigration is emerging due to economic and demographic changes within the country. China is presently going through one of the most sustained phases of economic development in its history; one that is associated with slow population growth and low fertility.

According to the preliminary results of China's 2010 census, the average annual population growth between 2000 and 2010 was 0.57 percent — just over half of what it was in the decade prior. While fertility rates in China have not been made officially public, estimates indicate that fertility among Chinese women has fallen below replacement level (under 1.8 in the first decade of the 21st century, compared with a replacement level of 2.1 children per woman). What's more, the country’s population is aging at a relatively fast pace: the proportion of people over the age of 60 in China was 13.3 percent in 2010, up from 10.4 percent in 2000. The growth of the working-age population (age 15 to 64) in China is thus projected to decline, from 0.95 percent per annum between 2005 and 2010 to 0.19 percent per year from 2010 to 2020, and to -0.23 percent annually between 2020 and 2030. This decline means that the era of surplus labor in China is quickly coming to an end.

Two million job vacancies were reported in the southeast coastal region of China in 2004, and labor shortages spread north into the Yangtze River and the north coastal region in 2005. To an extent, these shortages reflected bottlenecks in the labor market for certain types of workers within China, but more recent evidence suggests that the shortages may be as much structural as cyclical.

The pressure to import cheap labor from neighboring countries is rising. "Tens of thousands" of irregular workers are reportedly smuggled each year from Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries into southern China. Illegal brokers are reputed to earn $200 a head for laborers who will work for half the cost of a Chinese worker but three times the average wage in Vietnam. The majority of these irregular workers is almost certainly of Chinese ancestry from Vietnam, and speaks Chinese languages that allow them to blend into local populations.

But it is not only along China's southern border that immigration is occurring. Migrants are coming from the Korean peninsula in two distinct flows: the legal migration of entrepreneurs and industrialists to northern cities, and irregular flows of refuges from North Korea.

Regarding the former, China is South Korea's biggest trading partner, and Koreatowns have emerged in Beijing, Shenyang, Qingdao, Shanghai, and Weihai. The largest of these is Wangjing district in Beijing, where about one-third of the population, or some 100,000 people, in 2007 were from South Korea. The majority of the South Koreans in China are in middle-income or white-collar employment on tourist, temporary business, or other short-term visas.

Another 50,000 ethnic Korean Chinese (the chosonjok) — survivors of the Japanese-induced migration of Koreans into Manchuria in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and displaced by the economic reforms of the post-1979 period — are also estimated to be living in the district. While some Korean Chinese are in joint ventures with South Koreans, the district is a complex mix of distinct ethnicities. It is in the booming cities of coastal China where the cultural affinities of these ethnic Koreans have allowed them to develop partnerships with South Koreans from the early 1990s.

The second flow is of North Koreans fleeing conditions in their own country, though China does not recognize their claims for asylum. This flow was prevalent in the late 1990s, at a time of severe deprivation in North Korea. Increased border surveillance and lower expectations of what China might provide have reduced the flow, while increased numbers of North Koreans have made their way to South Korea and to other developed economies. The number of North Koreans in northeastern China appears to have declined from some 75,000 in 1998 to around 10,000 in 2009.

Official figures suggest that, overall, some 2.85 million of the 26.11 million foreigners who entered China in 2007 came for employment purposes. Of these, more than half a million were workers in joint ventures or wholly foreign-owned firms. Again, the majority were likely to have been skilled migrants from the developed world, including overseas Chinese from Europe, North America, and Australasia.

Some of these were almost certainly earlier migrants from China. However, many others are irregular, including perhaps 20,000 Africans in southern China. The largest share of African migrants is from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, and Mali. The majority appears to be traders, and their presence is the result of China's increasing involvement in Africa. In a trend that has been noted in other parts of the developed world, China is now experiencing immigration from areas where it has economic and political interests (migration of the Chinese to Africa is discussed below).

In addition to the immigration of foreign-born workers, China is also experiencing increased numbers of migrants entering the country for the purpose of study. China now ranks as a major destination for international students, with an estimated 238,184 foreign students in 2009, ahead of both Australia and Canada. South Korea accounted for more than one-quarter of the foreign-born students in China, followed by the United States and Japan with 7.8 percent and 6.5 percent, respectively. Though over 60 percent of international students in China were not in degree-seeking programs — not the case in the major destination countries of North America, Europe, and Australasia — some 74,472 foreign students were studying at the undergraduate level and 18,978 were studying at the postgraduate level.

As a result of this new trend of immigration, China is now planning to draft an immigration law that will seek to attract to China the people that it needs to support its development. Central to this endeavor will be the assignment of immigration roles to particular ministries. Most fundamentally, a much stronger database on the numbers, origins, and types of migrants in China is required. Whatever the challenges, it is a major sea-change for a country that has traditionally been concerned with emigration to begin dealing with immigration issues with which the developed world has been wrestling for some time.

As China develops economically and ages, perhaps the greatest consequence for migration and the West will be that China will contribute to an increasing competition for labor within the global system as it, too, must seek out workers for its labor market. China, with its vibrant economy, is now clearly a major participant in the global migration system and has become an emergent destination for migration.

Tradition of Chinese Migration

While the tradition of Chinese migration is long-standing, a distinction can be drawn between an "old" migration that lasted until the late 19th century and a "new" migration that dates from about the 1980s. The decades between these two migrations was a transitional period shaped by enormous change globally and within China itself that saw emigration severely curtailed relative to what had come before and what was to follow. The two periods of global conflict during World War I and World War II, which were separated by a profound economic depression, were followed by a period of tight control of migration in China under communist ideology until the early 1980s.

Though distinct, the old and new migrations are interconnected. The old migration created ethnic Chinese communities concentrated primarily in Southeast Asia (but also around the world) that survived the transition period — albeit often in reduced form — and that formed a global network of Chinese that has facilitated the new, accelerated migration taking place since the 1980s.

The changes in the migration habits of the Chinese are evident in terms of the overall ethnic Chinese population living outside of China. By the end of the 20th century, there were an estimated 33 million ethnic Chinese living overseas, an increase from around 22 million in 1985 and from 12.7 million in the early 1960s. Given the generally low fertility of overseas Chinese populations, this suggests the increasingly significant role of migration from China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan) over the second half of the 20th century.

The "Old" Chinese Migration

Traditionally, the Chinese heartland turned its back on overseas expansion, and only the southern Chinese engaged in widespread trade throughout Southeast Asia and into the Indian Ocean. Imperial governments on occasion banned movement overseas and contact with foreign powers.

Even though these laws were perhaps more honored in the breach than the observance, the result of centuries of Chinese economic and cultural dominance in eastern Asia was not a series of overseas colonies, but a loose network of trading posts. There, the Chinese were either marginalized or absorbed by indigenous populations, depending upon local conditions. This situation was quite distinct from that of expansionary Europe from the 16th century.

Perhaps significantly, it was not until the consolidation of European colonies in Asia from the mid-19th century that the Chinese moved overseas in large numbers, and they did so in Western ships. Some 6.3 million Chinese were estimated to have left Hong Kong between 1868 and 1939, and large numbers also left Xiamen (Amoy) and Shantou (Swatow).

It was a movement dominated by men going overseas to work as indentured laborers — the infamous coolie trade — although others traveled more independently to seek their fortunes in the goldfields of Australia and the west of North America and New Zealand. Some 5 million of the 6.3 million who left through Hong Kong were men. The majority moved to the economies in Southeast Asia that were being opened up by British and French colonial interests.

These Chinese migrants were sojourners: people who left home with the intention of returning rich, marrying, and settling down. The fact that many died overseas or decided to remain does not deny the essentially circular nature of this system, which was quite different from the migrations from Europe that were comprised supposedly of settlers.

We now know that many of those who left Europe also did so with the intention of returning, and so, in reality, both European and Chinese systems had a significant component of circular movement. The critical difference is that the Europeans were seen as settlers, while the Chinese were considered by both themselves and others as sojourners.

This particular identity of the early Chinese migration system was reinforced by the marginal position of Chinese migrants in destination societies. With some notable exceptions; e.g., in the Philippines and Thailand, they were not allowed to assimilate, even if they wanted to.

This was because the Chinese were deemed racially and culturally different, or because they were feared for their business acumen. Not that most Chinese migrants were rich merchants: the vast majority was poor and engaged in menial activities in both rural and urban areas. But a few entrepreneurs came to exert economic dominance within Southeast Asian societies out of all proportion to their numbers. This influence remains, with some modifications, to this day.

Transitioning into a Period of “New” Migration

The marginalization of most Chinese extended to their virtual exclusion from entry into the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand beginning in the 1880s, due to racist legislation that was not rescinded until after World War II. Thus, migration from China from the late 19th century until the late 1940s was, with some notable periods of interruption, directed primarily toward the then European colonies of Southeast Asia.

With the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, emigration from China became strictly controlled in what was almost a return to the Qing policies of the 16th century. The migration from China that did occur was primarily that of students to the Soviet Union and of specialist workers to certain developing countries, such as Tanzania. Any remaining migration was within the Chinese sphere.

Over 1 million migrants, mainly supporters of the defeated nationalist Kuomintang Party, fled to Taiwan around the time of the formation of the People's Republic. An equal number of migrants went to Hong Kong at the same time, followed by a continuous, if fluctuating, flow over the subsequent three decades. Almost half a million migrants entered Hong Kong between 1977 and 1982, for example.

However, the most significant migrations of the Chinese in the post-war period were not only to and from Hong Kong and Taiwan, but also from the peripheral parts of the Chinese world: ethnic Chinese migration from the independent countries of Southeast Asia, such as Malaysia and Indonesia, to Western countries.

At first, these migrations were mainly from the villages of the New Territories of Hong Kong to the United Kingdom. They seemed to be simply a variation on those that had gone before, to the extent that they involved, initially at least, uneducated men going to engage in unskilled work. Later, and particularly with the opening up of Canada and the United States from the mid-1960s, and Australia and New Zealand from the 1970s, a new type of migration began to emerge: the movement of families and educated and skilled people.

Two factors account for the shift in the migration patterns of the Chinese peoples. First, there were changes in the immigration policies of the potential destination countries that finally swept away the legacy of racist policies based on regions of origin. Second, the Chinese became increasingly capable of taking advantage of opportunities overseas.

Policy shifts in the country of origin, however, were also critical to the way migration was to develop. Once China began to open up after the economic reforms that were implemented from 1979, increasing numbers of Chinese began to go overseas. They left in small numbers at first, but in more significant numbers from the mid-1990s. The process had begun, however, during the transitional period four decades earlier with migration from the marginal parts of China, as well as from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Chinese ethnic communities of Southeast Asia.

Clearly, the Chinese were not the only ones to avail themselves of these opportunities, but they were (and continue to be) in the forefront of migration to North America and Australasia. Hong Kong pioneered these new Chinese migrations, but by the turn of the new century China had become a major source of migrants.

In the case of Canada, China became the principal source of landed immigrants beginning in 1998. The number of permanent immigrants from China to Canada peaked in 2005 at 42,292, before declining to 29,051 in 2009. In these two specific years, the Chinese accounted for 16.1 and 11.5 percent of the total permanent immigrant intake, respectively, up from just 2 percent of the intake in the late 1980s. In 2009-10, the number of immigrants from China to Canada increased to 30,197, but China lost its number one source country position, coming in third after the Philippines (36,578) and India (30,252).

The proportional increase in Chinese immigration to the United States has not been as notable as for Canada — just marginally faster than the growth of immigration as a whole. In absolute terms, the annual number of Chinese immigrants arriving in the United States increased from 14,421 in 1977 to 87,307 in 2006, before declining to 67,634 in 2010. The number of Chinese entering Australia has also grown; from just a few hundred each year in the early 1980s to over 6,700 by 2002, and to 14,611 by 2010-11.

The figures on Chinese going overseas as immigrants provide only part of the picture, however. Large numbers also go abroad temporarily as students and skilled workers.

In 2009, China was the principal source of foreign-born students to the two main destinations for international students in general — the United States and the United Kingdom — but was also the principal source of international students in Australia, Canada, Germany, Japan, and New Zealand, and was the second most important source of foreign students to France, the Netherlands, and Ireland.

China also figures prominently among skilled migrants granted access to the United States through the H-1B visa category, with 20,855 petitions approved for Chinese workers in fiscal year (FY) 2009. This figure is less than the 24,174 approved in FY 2008, but still up markedly from the 12,333 approved in FY 2000. However, China remains a distant second to India in this category, accounting only for about 10 percent of all H-1B visa approvals, compared with 48 percent for Indian applicants in 2009.

Thus, the opening up of China after the economic reforms implemented from 1979 has been accompanied by increased international population movements, some of which have led to longer-term and more permanent settlement. As a result, China-born populations in principal countries of destination have risen markedly in recent decades.

Those born in China and living in the United States increased from just 170,132 in 1970 to 286,120 in 1980, and to 1,570,999 by 2008. Moreover, by 2008 the Chinese diaspora (at 3.2 million) had emerged as the largest Asian ethnic group in the United States, and one that was increasing at a rate between four and five times faster than the growth rate of the total population of the country.

Other countries also saw marked increases. In Canada, some 345,520 people were recorded with a birthplace in China in the 2001 census, up from 168,355 in 1996. In Australia, it was estimated in 2008 that 259,095 people had been born in China, up from 142,781 in 2001, 111,009 in 1996, and 78,835 in 1991. Interestingly, the populations born in Hong Kong living in both Canada and Australia declined between 1996 and 2001, perhaps indicating migration back to their place of origin.

Chinese Migration Today

The current migrations both maintain continuity and display key differences when compared with the old migrations. The more balanced sex ratios and high skill levels have already been emphasized. Clearly, too, the destinations differ.

The current migrations both maintain continuity and display key differences when compared with the old migrations. The more balanced sex ratios and high skill levels have already been emphasized. Clearly, too, the destinations differ.

Very little legal migration takes place to the more traditional destinations of Southeast Asia — the settler societies of North America and Australasia are now the preferred choice — but the Chinese still play a key role in the economies of the region. However, they appear to have emerged as but one ethnic group in what are increasingly multicultural societies, rather than having maintained their status as Chinese sojourners looking back to China. The majority, while identifying themselves as Thai or Malay Chinese and being prideful of their heritage, may neither speak nor read Chinese and see themselves as Southeast Asians first and Chinese second.

One regional flow that does continue is to Hong Kong, where around 150 individuals each day (mainly the wives and children of permanent Hong Kong residents) are allowed into the Special Administrative Region. Although this migration might be seen as technically internal within China, it does provide one of the very few current examples of Chinese immigration for settlement in Asia.

Another important difference from previous migrations has been the recent emergence of Europe as a significant destination. Although hardly "new" since the Chinese have been going to European countries for well over 100 years, the numbers involved were fairly small until recently.

In addition to migrants from the Fujian and Guangdong provinces, migrants from Zhejiang and, increasingly, from provinces in the northeast figure prominently in the flows to Europe. Estimates of the number of Chinese in Europe around the year 2000 vary enormously — owing to the prevalence of irregular migration — from a low of 200,000 to 1 million or more, but all appear to agree on the recentness and rapidity of the migration. For example, the number of Chinese residents more than doubled in Italy and increased more than six fold in Spain between 1990 and 2000.

Migrants headed for Europe appear to be less skilled than those going to Australasia and North America, with large numbers moving into low-order services, trading, and manufacturing jobs. Large numbers of Chinese are also moving to Japan and the Russian Far East, while smaller numbers are going to other destinations as widely dispersed as the islands of the Pacific and countries in Latin America. In choosing their destinations, all of these migrants appear to be influenced by the global distribution of the Chinese as established by previous migrations.

Another increasingly significant destination for the Chinese has been Africa. China is now the African continent's leading trading partner, and the recent migration reflects the growing influence of the country as a global economic power. Estimates of the number of Chinese migrants on the continent range up to 750,000, although more cautious assessments of the number of those of Chinese origin, including all ethnic Chinese, place the number between 270,000 and 510,000, with one-third to half of these in South Africa. Nevertheless, there is a significant transient population of contract workers and merchants that might push the total toward the top end of the estimates.

Of greatest interest is the impact that these migrations have on the destination countries in Africa. China lost close to a million hectares of agricultural land to urbanization and the expansion of industry every year in the late 1990s, and the search for fertile ground in Africa and elsewhere is a strategy to guarantee future supplies, if required. Furthermore, competition from Chinese industries is undermining local industries, with reports of the number of locally-owned textile factories in Kenya declining markedly over recent years. Trends such as these, plus investment in raw material extraction, are likely to have significant impact on future migrations within and from Africa.

As in the old Chinese migration, the movement of unskilled men on short-term labor contracts still occurs, although today it is normally controlled by central or provincial government organizations. For example, at the end of 2001, it was estimated that some 460,000 workers from China were overseas on labor contracts and, over the previous 20 years, Chinese workers had served in about 180 countries and economies on contracts worth about $120 billion. Most of those contracts were in Eastern Asia, but the Chinese have also expanded to the Middle East and beyond.

Irregular Migration

One aspect of Chinese migration that has captured considerable attention has been the number of Chinese entering countries illegally as so-called "irregular migrants." The Golden Venture episode off the coast of New York in June 1993, in which 10 Chinese died trying to reach shore, and the incident at the port of Dover, England, in June 2000, in which 58 Chinese died in a cargo container, originally alerted authorities in both America and Europe to the magnitude of the problem.

Nevertheless, the Chinese represent a minority group among those smuggled into both the United States and Europe. The term "smuggled" is used in preference to "trafficked," as the majority of Chinese appear to enter willingly into illegal arrangements in order to facilitate their passage to the West, paying up to $50,000 or more for the privilege depending upon the destination and means of transfer. Considerable exploitation exists within the smuggling networks, particularly when migrants reach their destination and the smugglers are waiting to collect the balance of the agreed payment.

The majority of those smuggled are young men, although women are also represented in the flows. Most, though not all, of the irregular migrants come from Fujian Province. This province, paradoxically, is one of China's richer areas. Its relative openness to the outside world, as well as its residents' ability to pay the considerable fees charged by human smugglers, has facilitated this type of migration.

Smuggling routes are many and constantly changing, but some evidence suggests that the locus of the smuggling of Chinese is shifting from North America toward Europe and Japan. This may reflect the success of increased surveillance at U.S. borders, particularly since 9/11, as well as agreements between Chinese and U.S. authorities. The labor markets in the traditional U.S. destinations of New York and San Francisco may also have become saturated, leading smugglers to open new markets in Europe and elsewhere, including African countries. Europe and Japan also struggle with developing immigration policies comparable to those of Australasia and North America to cope with the large number of immigrants they now receive.

The majority of smuggled Chinese appear to go through Southeast Asia and then into Russia or Eastern Europe by air, before crossing the long and porous land borders into Western or Southern Europe. Although the sea route to North America captured so much public attention in the late 1990s, it is likely that the majority of smuggled Chinese reached diaspora communities in South and Central America and the Caribbean by air, before moving onward to the United States by sea or land.

The opening of more and broader channels for legal immigration may go some way toward managing the flows of migration, leading to a reduction in the number of expensive and hazardous irregular channels. Government-to-government agreements have also proved effective, demonstrating that if the Chinese government is convinced that there is international capital to be made through the reduction of people smuggling and trafficking, it will respond accordingly.

Looking Ahead: Towards Another Migration Transition?

After a long period of little international migration, people from China began moving overseas in increasing numbers after the economic reforms of 1979. There appears to be little evidence to indicate a slowing of these migrations in the near future. One concern in developed countries — particularly, perhaps, within Europe — is that with a base population of 1.34 billion, China could come to dominate the global migration system and change the character of destination societies.

However, the image of an imminent wave of migration out of China may be predicated more on fear than a calculated assessment of the evidence. The sharp increase in migration over the past few decades is likely, at least partially, to have been the result of years of enforced control of international movement.

The more likely scenario, of course, is that China will increasingly compete for migrant workers to fill gaps in its labor markets as the country’s working age population shrinks and the elderly, dependent population grows. China has truly emerged as a destination country for economic migration, and the world will be watching when China is ready to introduce and implement its new immigration policy.

Sources

Benton, Gregor and Frank Pieke (eds.). 1998. The Chinese in Europe. Hampshire: Basingstoke, Macmillan.

Brautigam, Deborah. 2009. The Dragon's Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Epstein, Gabby. 2010. "China's immigration problem", Forbes Magazine. Available online.

Hugo, Graeme. 2009. "Emerging Demographic Trends in Asia and the Pacific: The Implications for International Migration." In Talent, Competitiveness and Migration, eds Bertelsmann Stiftung and Migration Policy Institute. The Transatlantic Council on Migration. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung.

IIE 2011. Atlas of Student Mobility. New York, Institute of International Education. Available Online.

Laczko, Frank (ed.). 2003. "Understanding migration between China and Europe," International Migration, vol. 41(3), special issue.

Ma, Laurence J. C. and Carolyn Cartier (eds.). 2003. The Chinese Diaspora: Space, Place, Mobility, and Identity. Lanham, MD: Lanham, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

Ma Mung Kuang, Emmanuel. 2008. "The New Chinese Migration to Africa." Social Science Information, vol. 47 (40): 643-659.

Nyíri, Pal and Igor Saveliev (eds.). 2002. Globalizing Chinese Migration: Trends in Europe and Asia. Aldershot, Ashgate.

Pan, Lynn (ed.).2006. The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, second edition.

Pieke, Frank. 2011. "Immigrant China", Modern China, vol 37 (6).

Pieke, Frank N., Pál Nyíri, Mette Thunø and Antonella Ceccagno. 2004. Transnational Chinese: Fujianese Migrants in Europe. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Robinson, Courtland. 2010. North Korea: Migration Patterns and Prospects. San Francisco, CA: Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability. Available online.

Sinn, Elizabeth. 1995. "Emigration from Hong Kong before 1941: general trends," in Emigration from Hong Kong: Tendencies and Impacts. Ronald Skeldon (ed.)Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2000, pp. 11-50.

Sinn, Elizabeth (ed.). 1998. The Last Half Century of the Chinese Overseas. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Skeldon, Ronald. 2000. Myths and Realities of Chinese Irregular Migration. Geneva: International Organization of Migration.

Spencer, Jim, Petrice R. Flowers and Jungmin Seo. 2012. (Forthcoming). "Post-1980s Multicultural Immigrant Neighbourhoods: Koreatowns, Spatial Identity and Host Regions in the Pacific rim." Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.

Thunø, Mette (ed.). 2007. Beyond Chinatown: New Chinese Migration and the Global Expansion of China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2008 American Community Survey. Accessed from Steven Ruggles, Matthew Sobek, Trent Alexander, et al., Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 3.0. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center, 2004.

Wang Dewan, Cai Fang and Gao Weshu. 2005. Globalization and Internal Labor Mobility in China: New Trend and Policy Implications. Beijing: Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Wang, Gungwu. 2000. The Chinese Overseas: From Earthbound China to the Quest for Autonomy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

World Bank. 2011. Migration and Remittances Factbook 2011. Washington DC: The World Bank.

Xinhua. 2010. "China Plans Draft Immigration Law", China Daily. Available online.

Zhang Feng. 2003. "Recent Situation of Economic Development and Migration Employment in China," in Migration and the Labour Market in Asia: Recent trends and Policies. Paris: OECD, pp. 185-191.