You are here

Court-Ordered Relaunch of Remain in Mexico Policy Tweaks Predecessor Program, but Faces Similar Challenges

Migrants enrolled in the Migrant Protection Protocols are processed by U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers. (Photo: Glenn Fawcett/U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

The Biden administration’s relaunch of the controversial Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), known informally as the Remain in Mexico policy, puts it in the uncomfortable position of implementing a Trump-era plan that it is simultaneously trying to dismantle and which President Joe Biden has vocally denounced. MPP allows U.S. authorities to send migrants, many of them asylum seekers, who arrive at the U.S.-Mexico border without proper documentation back to Mexico to wait out the duration of their U.S. immigration court proceedings.

During MPP’s two-year lifespan in the Trump administration, from January 2019 to January 2021, approximately 68,000 migrants were enrolled. The program contributed to growing immigration court backlogs, encountered legal challenges, and had questionable success in deterring migrants from illegally crossing the border.

The new version of Remain in Mexico will start at one border crossing the week of December 6, and eventually will be rolled out across the entire southwest border. In what may be a significant expansion, migrants from any country in the Western Hemisphere will be eligible to be enrolled in MPP. During the last iteration, Mexico accepted migrants only from Spanish-speaking countries and Brazil, which notably excluded individuals from Haiti. The arrival of thousands of Haitians at the Texas border in September generated political consternation, and the new version of the program may include Haitians for the first time.

There will be some other changes to the program, many based on demands by the Mexican government. Among them are that MPP enrollees will be able to receive a COVID-19 vaccine; indeed, vaccination will be required for migrants to re-enter the United States to attend their hearings. The United States will also aim to complete individual MPP court cases within six months, and provide migrants with greater access to legal aid and more information about their situation. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has also promised to exempt some categories of vulnerable individuals from Remain in Mexico, including the elderly, LGBTQ people, and those with physical or mental disabilities. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers will also ask migrants whether they fear going back to Mexico, which could trigger a screening interview with an asylum officer to determine whether to exempt them from MPP. Under the Trump administration, migrants had to proactively state this fear without prompting before they could be referred to a screening interview.

Despite these adjustments, the broad consequences of MPP for migrants and the U.S. immigration system are likely to be similar given built-in program challenges remain fundamentally unchanged.

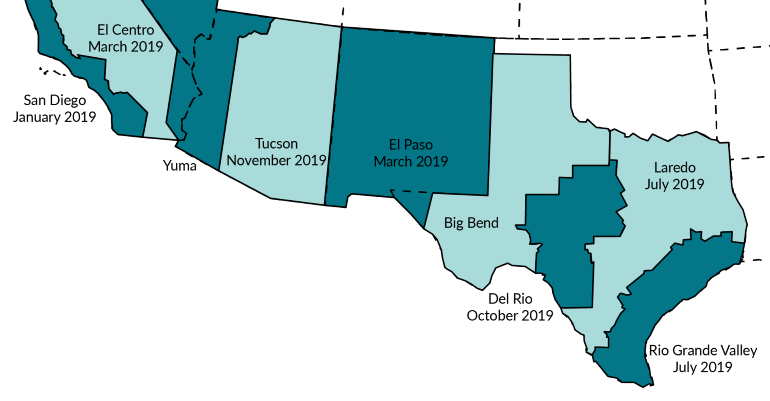

The Trump administration announced MPP as part of an arsenal of policies designed to deter migrants from reaching the U.S. southern border. Remain in Mexico started in the San Diego sector in early 2019, and by the end of the year some migrants encountered all along the border were being enrolled.

Figure 1. U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Sectors and Date of MPP Implementation

Note: Although the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) were never officially implemented in the Big Bend and Yuma sectors, migrants encountered in those sectors were sometimes transported to El Paso and El Centro, respectively, to be enrolled into MPP there.

Source: MPI artist rendering.

Of the approximately 68,000 participants in the original MPP, more than 32,000 were ordered removed, nearly 9,000 had their cases terminated, and just 723 were granted asylum or some other kind of immigration relief. The remaining 27,000 still had pending cases in U.S. immigration court when the Biden administration announced the suspension of MPP on its first day in office in January 2021. Many migrants with pending cases had not had a hearing since at least March 2020, when MPP hearings were paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Advocacy groups brought legal challenges to MPP during the Trump administration, but were ultimately unsuccessful. A federal court blocked the implementation of MPP in April 2019 but was overruled by the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and later the Supreme Court.

Biden Administration Tried to End MPP and Admit Enrollees

Immediately upon entering office, the Biden administration announced it was suspending new enrollments in MPP as part of what it described as a focus on humane border policies. In mid-February, it started processing into the United States MPP participants who were waiting outside the country—mainly in Mexico, but some in their home countries—for their court hearings. On June 1, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas formally ended the program, and later that month DHS allowed MPP participants whose cases had been terminated or who had previously been ordered removed in absentia to be rescheduled for fresh hearings. By August, 13,000 MPP participants had been allowed to pursue their court cases from within the United States.

Migrants eligible to re-enter the country first registered with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which verified their status as MPP participants. These agencies determined whom to prioritize for re-entry, based on how long individuals had waited in Mexico and their specific vulnerabilities. MPP enrollees determined to be involved in criminal or terrorist activities or whose detention was otherwise legally mandated were detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) during this processing phase. However, this was a fraction of the MPP population, and most individuals were paroled and released into the United States—usually to shelters along the border, from where they could travel elsewhere—for the remainder of their court proceedings. Immigration courts in Florida and Texas received the most cases transferred from the MPP border courts, suggesting a preference of many MPP participants to move to those destinations.

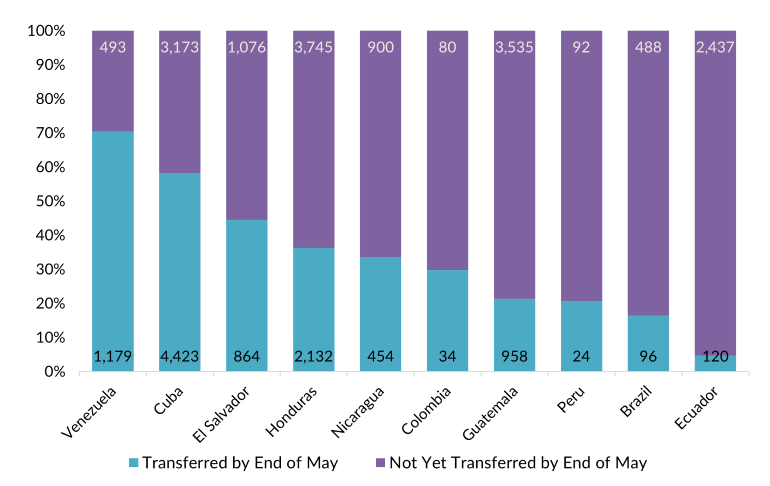

However, not all MPP enrollees were admitted. Although most eligible Cubans and Venezuelans were allowed in by the end of May, much smaller shares of eligible individuals from Guatemala and Honduras were permitted entry (see Figure 2). One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that Guatemalans and Hondurans may have been more likely to abandon their cases and return to their origin countries during the yearlong pause in MPP hearings, possibly due to difficult living conditions in Mexico. It is also possible that officials deemed Cubans and Venezuelans to be higher priorities for processing. Whatever the reason, there was little opportunity to fix it: when the courts ordered MPP to be reinstated in August, the federal government abandoned its efforts to bring MPP participants into the United States.

Figure 2. Share and Number of MPP Cases Transferred into the United States by Nationality, January-May 2021

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), “MPP Transfers Into United States Slow and Nationality Inequities Emerge,” June 17, 2021, available online.

Legal Challenges Force Reinstatement

As the Biden administration tried to wind down Remain in Mexico, it faced lawsuits from Texas and Missouri challenging first the program’s suspension and then, in June, its official termination. The states’ attorneys general argued the termination process was unlawful, violating both administrative and immigration law. The lawsuits continued a pattern of state intervention in federal immigration policy via litigation, which gained steam during the Obama administration and continued through President Donald Trump’s years. Indeed, almost all successful challenges to the Biden administration’s immigration actions thus far have been brought by states, rather than by individuals or organizations.

In this case, Texas and Missouri claimed that the end of MPP would cause federal officials to release more migrants into their states, saddling them with the cost of providing drivers’ licenses, education, health care, and other services. In August, Judge Matthew J. Kacsmaryk of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas sided with the states and prevented the Biden administration from terminating MPP; both the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court refused to block the injunction. DHS has attempted to address the legal issues by issuing a new termination memo, now under review by the courts, providing more robust arguments that the benefits of ending the program outweigh the benefits of maintaining or amending it.

In the meantime, the administration will restart MPP in compliance with the court order. To that end, it engaged in negotiations with Mexico and is setting up temporary border facilities, sometimes referred to as tent courts, to hear MPP cases.

MPP proved difficult for migrants, who were massed in Mexican border communities, as well as for the communities themselves. In the face of limited space in Mexican border shelters, many migrants resorted to living in outdoor camps, vulnerable to criminals and exposed to the elements. The advocacy organization Human Rights First documented at least 1,544 cases of murder, rape, torture, kidnapping, and violent assault against MPP participants. Mexico provided only temporary work permits to some MPP enrollees, making it more difficult for migrants to support themselves during their long waits. In negotiations to restart the program, Mexico demanded that the United States work to improve migrants’ stay in the country, such as by providing resources to shelters and migrant-focused aid groups. The United States announced it would work with Mexico to provide safe shelters, secure transportation to U.S. ports of entry to attend hearings, and offer work permits and other services in Mexico, but it is not yet clear the degree to which these will be available in practice.

With the Biden administration under court instruction to restart MPP, Mexico may have extracted other promises from the United States unrelated to Remain in Mexico. In the months following the court order, the U.S. government has sent more than 8 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines to Mexico. The United States also announced an investment in a program in southern Mexico similar to one backed by the administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador for which he has repeatedly sought U.S. support, which is intended to reduce deforestation, raise farmers’ incomes, and help stem migration. While these efforts were not explicitly tied to the reinstatement of MPP, they may have made the Mexican government more amenable to cooperate.

Impacts of MPP on Migrants and Immigration System

If deterring migrant flows was the motivation for introducing MPP, there are reasons to doubt whether it was effective. Meanwhile, its impacts on the lives of migrants and the U.S. immigration system writ large were significant. Tens of thousands of asylum seekers were ordered removed from the United States, often without access to a lawyer or even being present during their hearings. And immigration court backlogs grew by leaps and bounds. It is likely that many of these outcomes will be repeated in a revived MPP.

Migrants Ordered Removed with Little Recourse

One of MPP’s main challenges for migrants was the difficulty of attending court hearings. Of the 32,000 MPP enrollees ordered removed, 88 percent of rulings occurred in absentia, meaning the migrant did not appear at the hearing. While it is impossible to know precisely why each person was absent, many cases can likely be explained by inadequate communication, lack of legal representation, and migrants relocating.

The vast majority of migrants in MPP lacked legal counsel. At the time the program was shut down in January, just 9 percent of MPP enrollees had had legal representation at some point in the process. In comparison, 56 percent of all people with pending cases in U.S. immigration court had representation at some point in their proceedings in fiscal year (FY) 2021, whether arranged by them or provided by a nongovernmental organization or state or local entity (there is no federal requirement to offer legal representation in immigration cases). Among asylum seekers with pending cases, that share is even higher, at 84 percent. While not directly comparable to MPP cases, the difference nevertheless points to the difficulty of securing representation under Remain in Mexico.

In addition to providing legal defense, lawyers can offer clarity about the steps in the court process and keep their clients informed about hearing dates and times. It is unsurprising, then, that unrepresented migrants facing legal proceedings inside the United States who are not detained tend to receive more in absentia orders than those who are represented. This trend was replicated in MPP.

Further, CBP, the agency that enrolled migrants in MPP, often provided insufficient addresses for migrants sent back to Mexico, making it nearly impossible for courts to communicate with them about changes to their hearing time or location (this communication is done by mail). Researchers’ analysis of a sample of charging documents issued to MPP participants found that 93 percent listed only a city or region as the migrant’s address. Without an effective way to be informed of changes, it is little wonder that many migrants missed their hearings.

It is also possible that difficult conditions in Mexican border towns caused some migrants to move elsewhere or return to their origin countries. Some who relocated may have abandoned their U.S. court cases, while others may have intended to continue pursuing them but for various logistical or practical reasons were unable to return and attend their hearing.

MPP’s Mixed Record as a Deterrent

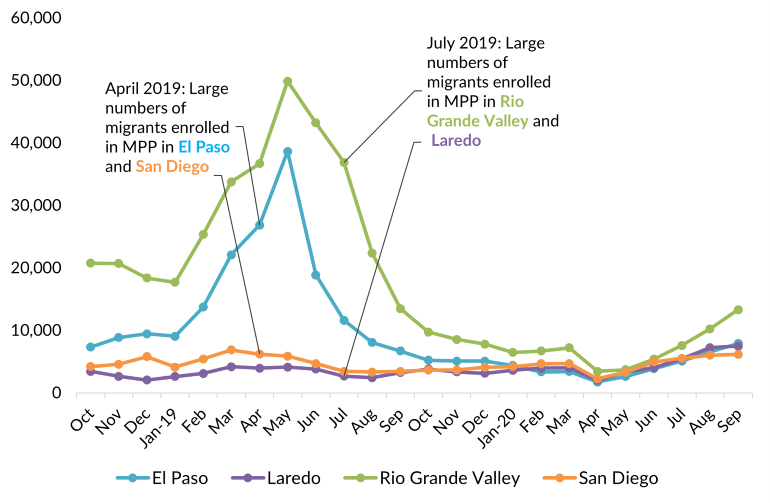

Remain in Mexico was intended to deter migrants from illegally entering the United States, but it is not clear that it was successful in this regard. Although border apprehensions declined in some places after MPP was implemented in 2019, there was no consistent pattern. For example, in both the San Diego and Rio Grande Valley CBP sectors, apprehensions had already started to decline before large numbers of migrants were enrolled in MPP. Given that they declined even more afterwards, this could indicate a deterrent effect in those sectors. However, in El Paso apprehensions continued to increase even after large numbers of migrants were enrolled in MPP, and it took longer for apprehensions to decline. Meanwhile, in Laredo apprehensions were dropping at a faster rate before migrants started to be enrolled into MPP in large numbers, and the rate of decrease slowed after MPP was implemented. So while apprehensions ultimately declined across the board, it is not clear that Remain in Mexico was the determining factor in deterring unauthorized migration.

Figure 3. Encounters of Migrants in Select U.S. Border Patrol Sectors, FY 2019-20

Note: In April, Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) enrollment in the El Paso sector was 979, up from 40 the previous month; in San Diego it was 1,328, up from 163 the previous month. In July, MPP enrollment in Laredo was 2,951, up from 16 the previous month; in Rio Grande Valley it was 1,106, up from one the previous month.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector Fiscal Year 2019,” updated November 14, 2019, available online; CBP, “U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector Fiscal Year 2020,” updated November 19, 2020, available online; TRAC, “Details on MPP (Remain in Mexico) Deportation Proceedings,” accessed November 22, 2021, available online.

The equivocal deterrent effect may be explained by the fact that migrants’ chances of being placed in MPP were never certain. No more than 20 percent of migrants attempting to enter the country illegally were ever placed in MPP during a given month. It is logical that the Biden administration will not likely seek to put more people in MPP than Trump did, since doing so would run counter to its argument in court that the program should be terminated. Further, dramatically increasing caseloads would make it harder for the administration to live up to its commitment to Mexico to conclude cases within six months.

Also, other changes in immigration enforcement around the time that MPP was implemented in 2019 likely had their own deterrent effects, making it more difficult to judge the program’s direct impact. Mexico, for example, stepped up immigration arrests in spring 2019 in response to U.S. pressure. Mexican authorities cracked down on highway routes that had become common for smugglers transporting migrant families north, and some bus companies started requiring customers to demonstrate legal status in the country before they could buy tickets. After five months of consistently increasing apprehensions, Mexican authorities made 31,000 apprehensions in June 2019, the highest monthly number on record. That same month, U.S. immigration arrests on the border started to decline, suggesting that rising apprehension numbers in Mexico were very closely correlated with decreasing flows at the U.S. border. Weeks later, the United States implemented a rule making ineligible for asylum any migrant who crossed the border illegally after passing through a third country if they had not sought asylum there first. In the fall, it started sending some migrants to Guatemala to seek asylum there instead.

MPP was thus part of a network of policies in both the United States and Mexico that led to a decrease in migration to the border in the latter half of 2019 by blocking access to U.S. territory or asylum. While Remain in Mexico may have contributed to a perception that it would be harder to cross the border, it is not clear that the program was an effective deterrent on its own.

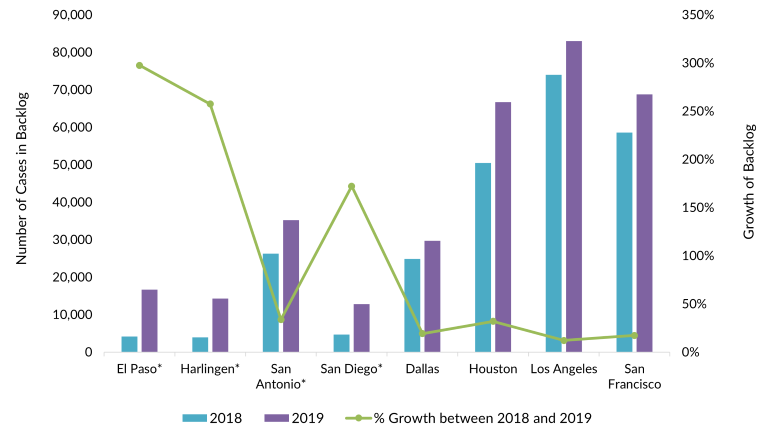

Swelling Backlog in Immigration Courts

MPP dramatically and unevenly increased backlogs in immigration courts along the U.S.-Mexico border. MPP cases were scheduled mainly in four court jurisdictions—San Diego, California; and El Paso, San Antonio, and Harlingen, Texas—and contributed to backlogs that grew faster in these courts than in others in those two states. Backlogs have grown across the immigration court system and, in terms of absolute numbers, were higher in major cities. But after MPP’s implementation, backlogs in courts hearing many MPP cases expanded faster than others: while backlogs in four non-MPP courts in California and Texas grew by between 12 and 32 percent between 2018 and 2019, the San Antonio court’s backlog rose by 34 percent, San Diego’s by 172 percent, Harlingen’s by 258 percent, and El Paso’s by 298 percent. For courts unaccustomed to this level of case volume, the MPP case surge was overwhelming.

Figure 4. Case Backlogs in U.S. Immigration Courts, FY 2018-19

* El Paso, Harlingen, San Antonio, and San Diego are the courts hearing most Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) cases.

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, “Immigration Court Backlog Tool,” accessed November 22, 2021, available online.

In the new iteration of Remain in Mexico, the Justice Department will assign 22 immigration judges to hear solely MPP cases. In 2019, however, DHS reportedly estimated that it would require at least 100 judges to make a dent in the backlog.

As of October, the U.S. immigration court system had an overall backlog of 1.4 million cases. As the Biden administration restarts Remain in Mexico, concentrating cases in just four court jurisdictions would likely further exacerbate this backlog.

MPP as Complement to Expulsions Policy

Under the Biden administration, similar to under Trump’s, the resumed MPP will be part of a web of policies making it difficult for migrants to access U.S. territory. Most notably, it will join a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) public-health order issued in March 2020 that authorized DHS to immediately expel migrants crossing the border illegally or lacking proper documentation. The Biden administration has continued that expulsions policy, known as Title 42, which it claims is based in public health rather than immigration strategy, and may use MPP as a complement to further slow releases of migrants into the United States. In FY 2021, more than 60 percent of Border Patrol encounters of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border resulted in expulsion under Title 42.

The new Remain in Mexico policy may focus on migrants who have not been subject to Title 42. Currently, migrants from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras are most commonly expelled under the public-health order, while migrants from other countries are expelled much more rarely. In FY 2021, the Border Patrol made 367,000 arrests at border of migrants from other countries. The largest shares of those came from Ecuador, Brazil, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Haiti, and Cuba. Just 8 percent of these arrests resulted in Title 42 expulsions. Mexico has refused to accept expulsions of these countries’ nationals, and the United States rarely conducts expulsions by plane to migrants’ countries of origin with the notable exceptions of Ecuador, and, recently, Haiti. However, Mexico has agreed to accept a broader array of nationalities under MPP. Last time MPP was in effect, migrants from Brazil, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela were among those most commonly enrolled, and it is possible that the administration will follow the same practice, picking up where Title 42 leaves off.

Further, although Mexico accepts expelled Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Salvadorans, some Mexican border states have refused to receive families with young children. The United States may also focus MPP on such families if Mexico agrees.

However, the future of Title 42 is uncertain. It has faced sharp backlash from some of the Biden administration’s supporters. A class-action lawsuit challenging the use of Title 42 against families is ongoing: a federal district court blocked the federal government from expelling families in September, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit allowed expulsions to continue while the case proceeds. If the courts ultimately block the use of Title 42 for expulsions—for families or for all migrants—or the CDC revokes its order, MPP could become a more central element of the Biden administration’s border policy. The court order to reinstate MPP may thus become a convenient tool for the administration, which is reportedly divided about Remain in Mexico but may be glad to point to the courts for tying its hands.

All the While, the Legal Battle Continues

The fate of MPP will likely rest with the courts. The Fifth Circuit is weighing whether the administration’s October termination memo is sufficient to replace its original rationale for dismantling the program, which would make the existing legal challenge moot and allow MPP to end.

Even if the appeals court does determine as much, Texas and its allies will likely again challenge the new termination memo. Either way, the case is likely to return to the Supreme Court. At the same time, challenges from immigrant advocates to the original MPP are pending. The lawsuit against Remain in Mexico filed by a coalition of advocacy organizations during the Trump administration is currently paused, and the plaintiffs could simply amend their complaint to challenge the Biden administration’s version of the program. Thus, no matter what, the Biden administration will likely be busy defending the future of MPP.

Sources

American Immigration Council. 2021. The “Migrant Protection Protocols.” Fact sheet, American Immigration Council, Washington, DC, October 2021. Available online.

Carranza, Rafael. 2019. How Trump’s ‘Remain in Mexico’ Program Affects Arizona Border Despite No Formal Policy. Arizona Republic, October 10, 2019. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Jessica Bolter. 2020. Interlocking Set of Trump Administration Policies at the U.S.-Mexico Border Bars Virtually All from Asylum. Migration Information Source, February 27, 2020. Available online.

Eagly, Ingrid V. and Steven Shafer. 2015. A National Study of Access to Counsel in Immigration Court. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 164 (1): 1-91. Available online.

Executive Office for Immigration Review. 2021. Adjudication Statistics: Current Representation Rates. Updated October 19, 2021. Available online.

Green, Emily. 2021. The Biden Admin Is Considering Reviving Trump’s ‘Remain in Mexico’ Policy for Migrants. Vice News, August 18, 2021. Available online.

Human Rights First. 2021. Delivered to Danger: Trump Administration Sending Asylum Seekers and Migrants to Danger. Updated February 19, 2021. Available online.

Instituto para las Mujeres en la Migración (IMUMI). 2020. Recursos para entender el Protocolo “Quédate en México.” N.p.: IMUMI. Available online.

Mayorkas, Alejandro. 2021. Memorandum from the Secretary of Homeland Security to Troy A. Miller, Acting Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection; Tae D. Johnson, Acting Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; and Tracy L. Renaud, Acting Director, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Termination of the Migrant Protection Protocols Program. June 1, 2021. Available online.

Mexican Ministry of Foreign Relations. 2021. Información sobre diálogos en materia migratoria con el Gobierno de los Estados Unidos. Press release, November 26, 2021. Available online.

Miroff, Nick and Kevin Sieff. 2021. U.S. and Mexico Reach Deal to Restart Trump-era ‘Remain in Mexico’ Program along Border. Washington Post, December 1, 2021. Available online.

Montoya-Galvez, Camilo. 2021. U.S. Finalizes Plan to Return Migrants to Mexico Under Trump-Era Policy as Soon as Next Week. CBS News, December 2, 2021. Available online.

Morales, Carlos. 2019. Migrant Protection Protocols Quietly Expands to Big Bend Sector. Marfa Public Radio, September 13, 2019. Available online.

Ortiz Uribe, Mónica. 2021. US Plans to Deliver 8.5 Million COVID Vaccines to Mexico ‘in the Coming Weeks.’ El Paso Times, August 10, 2021. Available online.

Rosenberg, Mica, Kristina Cooke, and Reade Levinson. 2019. Hasty Rollout of Trump Immigration Policy Has ‘Broken’ Border Courts. Reuters, September 10, 2019. Available online.

Silvers, Robert. 2021. Memorandum from the Under Secretary for the Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, and Office of Operations Coordination, Guidance Regarding the Court-Ordered Reimplementation of the Migrant Protection Protocols. December 2, 2021. Available online.

State of Texas, State of Missouri v. Joseph R. Biden, Jr. 2021. No. 2:21-cv-00067-Z. U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, Defendants’ First Supplemental Notice of Compliance with Injunction, October 14, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. No. 2:21-cv-00067-Z. U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, Memorandum Opinion and Order, August 13, 2021. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2021. Details on MPP (Remain in Mexico) Deportation Proceedings. Accessed November 22, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Immigration Court Backlog Tool. Accessed November 22, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. MPP Transfers into United States Slow and Nationality Inequities Emerge. TRAC, June 17, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2021. Explanation of the Decision to Terminate the Migrant Protection Protocols. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

The White House. 2021. Readout of President Biden’s Meeting with President Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico. Press release, November 19, 2021. Available online.

Wong, Tom K., Pierinna Bocca-Diaz, Michelle Gonzalez, and Valery Moya-Laurito. 2019. Seeking Asylum: Part 2, Appendix 1. San Diego: U.S. Immigration Policy Center. Available online.