You are here

Criminalizing Irregular Migrant Labor: Thailand’s Crackdown in Context

A Cambodian migrant worker at a construction site in Pattaya, Thailand. (Photo: Emmanuel Maillard/ILO Asia Pacific)

Over the past two decades, Thailand has become an attractive destination for migrant workers from neighboring countries. An estimated 4 million migrants—primarily from Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos—were employed in Thailand in 2017, comprising roughly 6 percent of the country’s population. Historically, most of these migrants moved irregularly across borders, either on their own or through informal brokers who transported them and organized employment. Today, many still lack legal status.

The Thai government is making a serious attempt to change these patterns. In June 2017, it announced a new royal decree on migrant labor, under which employers will face steep fines for employing unauthorized immigrants—up to $24,000 per worker. Foreign workers without documentation face severe penalties as well, including up to five years in prison.

The decree is not the government’s first attempt to crack down on migrant workers. Rather, it is the latest—and perhaps most stringent—step in an ongoing series of efforts to control migrant labor, in part by criminalizing irregular movement and employment. These moves toward greater regulation have often had unintended consequences for migrants, their families, and mobility patterns more broadly. For example, the announcement of the decree created insecurity and a heightened sense of vulnerability across migrant communities. Thousands of Burmese, Cambodian, and Laotian workers began returning home almost immediately, sparking fears of a mass exodus. These concerns were not unwarranted: In 2014, threats of a crackdown against migrant workers resulted in 220,000 Cambodians leaving Thailand over a two-week period.

Seeking to avoid a similar exodus, the Thai government quickly backpedaled, announcing a delay of implementation of the 2017 decree—which officials insist will be followed by a zero-tolerance approach. Migrants now have until January 1, 2018 to obtain documents before the law is implemented. While this move has had some impact on curbing returns, tens of thousands of migrants (many at the request of their employers) have still returned home, where they hope to obtain documentation enabling them to return to Thailand legally.

This article describes contemporary patterns of labor migration in Thailand, outlines key elements of the new law, and considers the potential impacts of increased regulation and criminalization of irregular movement in the region. In doing so, it focuses on Cambodian migration to Thailand—the second-largest flow into the country and that which was implicated in the 2014 exodus—by drawing on mixed-methods research the lead author has conducted in Cambodia annually over the past decade.

Overview of Cambodian Migration to Thailand

Thailand has become a key destination for labor migrants from neighboring countries, primarily Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos, in the past two decades. Steady infrastructure improvements and economic development, which began in the 1960s and boomed in the 1980s when Thailand shifted to an export-driven economy, created a demand for migrant labor. Since then, Thailand has transformed from a country of net emigration to one of net immigration, and further to a top migration destination in Asia.

Today, between 800,000 and 1 million Cambodians live and work in Thailand. Alongside Burmese and Laotian workers, they form the backbone of the country’s fishing, construction, and agricultural sectors. In 2014 migrants comprised 75 percent of the fisheries workforce and 80 percent of the construction workforce—two key sectors of the Thai economy—according to United Nations data. While Cambodians are drawn by Thailand’s higher wages and greater availability of jobs, they are also responding to a lack of opportunities in rural parts of Cambodia, where poverty, high unemployment, a growing youth population, environmental stress, and rising levels of household debt have motivated emigration. As migrant networks have grown, increasing numbers of households (particularly those in communities in northwestern Cambodia) have become reliant on migration to and/or remittances from Thailand.

As the foreign-born population has grown, the Thai government has become increasingly concerned with regulating and controlling labor migration. Thailand’s efforts to formalize management of these migration flows began in 1992, when the Royal Thai government created a registration process for migrant laborers in ten provinces along the Myanmar-Thailand border. In 2002 and 2003, the practice was extended through bilateral agreements between the Royal Thai government and Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos. The memoranda of understanding created a formalized process of migration and employment for low-skilled workers. During this time Thailand also developed a national verification process, which allowed migrants who had arrived via irregular channels to obtain a quasi-legal status and permission to work for two years.

National verification was intended as a stop-gap measure to regulate the migrant labor force through the regularization of foreign workers already present in Thailand. However, the costs, barriers, and limited benefits of legal migration have meant that the vast majority of Cambodians migrating to Thailand continue to do so through irregular channels, sustaining the need for further temporary registration programs. Would-be migrants avoid formal channels for good reason: To legally migrate to Thailand, the typical Cambodian would need to pay more than US $700 for documents and other fees, and wait three to six months for approval. In contrast, travel with a broker costs a fraction of the price (typically US $100-150) and can be arranged in a matter of days.

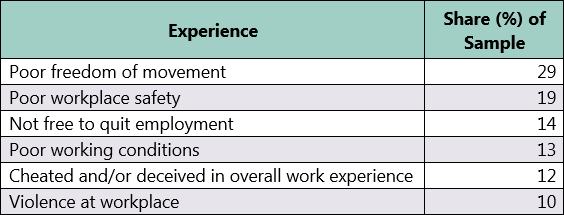

While irregular movements are common and easily facilitated, they are not without risk. Thailand deports approximately 50,000 to 100,000 Cambodians each year. Moreover, unauthorized migrants routinely face many forms of vulnerability and exploitation (see Table 1).

Table 1. Experiences Reported by Cambodians Deported from Thailand, 2012

Note: The study surveyed 402 deported Cambodian migrant workers.

Source: UN Action for Cooperation against Trafficking in Persons, Migration Experiences of Cambodian Workers Deported from Thailand in 2009, 2010, & 2012 (Bangkok: UN Development Program, 2015), available online.

Cracking Down on Unauthorized Workers

A shift in Thai immigration policy began in 2014, when a coup d’etat brought a military government to power. The new government immediately announced a crackdown on migrant workers. While this never materialized, the threat itself led to the mass exodus of 220,000 Cambodians, approximately one-third of the Cambodian population then working in Thailand. The returns, though short lived, generated chaos on both sides of the border. In Cambodia, returning workers struggled with joblessness, debt, and a lack of food, shelter, and medical care. Remittances fell, causing concern among microfinance providers in areas where migrant earnings are used to repay debts. In Thailand, employers faced labor shortages, causing construction delays, cuts in production, and concerns about a potential recession in an already-strained economy.

In response to the exodus, both the Thai and Cambodian governments announced new efforts to streamline registration to allow migrants who had left to return to Thailand cheaply and quickly. These efforts, however, were poorly coordinated and implemented, leading most migrant workers to return through irregular channels.

Following the 2014 exodus, the Thai government initiated a new form of documentation (so-called pink cards) that allowed foreigners to work temporarily in Thailand while they completed a national identity verification process. While many Cambodians registered for pink cards during this period, far fewer were able to fulfill the requirements for national verification, which included obtaining a passport. Migrants reported a range of barriers to securing documents, including high costs, inefficient bureaucracy, constantly shifting requirements (including the need to re-register following a change of employer), a lack of transparency and information about the process, and corruption.

Since the exodus, the Thai government has offered migrants pink-card extensions and opportunities to re-register for temporary documentation, but also required those who had expiring residency documents issued between 2009 and 2013 to shift to the temporary pink-card system. This move created further confusion among foreign workers, and was criticized for narrowing the rights of workers: The pink cards limit movement more severely than under previous forms of registration, and strip migrants of social protection entitlements.

The 2017 Decree: Assessing Immediate Impact

Read alongside this history, the 2017 decree might be seen as just another attempt to better control and regulate migration. However, the law is a notable departure in terms of the increased consequences it outlines for the employers of unauthorized workers. It is marked by three shifts:

- It establishes penalties for working without proper documentation. Migrants can be fined from 2,000 to 100,000 Thai baht (between US $60 and $3,022), and/or imprisoned for up to five years. These penalties are reproduced from earlier laws. Further, the penalty for engaging in work not specified on permits was raised, from the 2008 level of 20,000 baht to 100,000.

- It increases the penalties for employing workers without proper documentation. Employers can face fines from 400,000 to 800,000 baht (between US $12,092 and $24,184) per unauthorized worker. Further, employers can be fined 400,000 baht for employing workers to perform work not specified on their permit. Prior to this period employers hiring a foreigner without proper documentation could face fines ranging from 10,000 to 100,000 baht per worker.

- It introduces new penalties for employers who confiscate migrants’ personal documentation or work permits, with penalties of up to six months in prison and/or a fine of up to 100,000 baht.

The Thai government has asserted that the law is necessary to prevent human trafficking and labor exploitation. Human-rights organizations have called the law draconian, and pro-business groups have pointed to a range of negative consequences for employers: the costs for small-business owners, potential labor shortages, and the difficulty of implementation. Others have criticized the process, noting that the decree came without public consultations or hearings.

For migrant workers, implementation of the law will make it far riskier to work in a role outside that specified on their permit. Meanwhile, moving within the country, choosing employment sites, and changing employers will also likely become costlier and more difficult as employers respond to the law. The renewed threat of long prison sentences and high fines may also generate new forms of exploitation, as migrant workers already widely report paying bribes to local police to avoid being deported or jailed. Finally, it is important to underscore the severity of punishing unauthorized workers with up to five years in prison. Such harsh penalties are rare, even among countries known for being tough on irregular migrants.

In the days following announcement of the law, confusion reigned on both sides of the border. The Cambodian government instructed unauthorized Cambodians in Thailand to stay put and stay quiet while it negotiated with the Thai government. Yet migrant returns increased significantly: In the two weeks following the announcement, more than 7,200 workers returned to Cambodia. Tens of thousands of others returned to Myanmar and Laos. Many reported returning with the aim of obtaining passports, to facilitate re-entering Thailand and going back to their employment sites. Hoping to deter further irregular movement, the Cambodian government closed all unofficial border checkpoints in the northwest province of Banteay Meanchey, disrupting day labor flows and frustrating those who aimed to return quickly to Thailand.

While likely to be short-term, these returns are not without consequence. For instance, many migrants rely on their wages to repay personal and household debts. In Cambodia, indebtedness commonly drives migration, and debt repayment is a primary use of remittances. As a result, even a brief hiatus in labor abroad may have important consequences for household bottom lines.

Moreover, migrants are incurring significant costs to “get legal” in the wake of the new law. The context of large-scale returns and uptick in workers seeking passports has paved the way for rampant exploitation and corruption. Normally, Cambodian passports are only available in Phnom Penh, entailing a costly, risky journey for unauthorized workers in Thailand to obtain documents. However, the need for documentation has created a thriving market for agents who obtain passports for migrants while they remain in the country. The Phnom Penh Post has reported that some migrants pay agents in Cambodia between US $600 and $800 to obtain a passport remotely, compared to the official price of $100 for a regular passport or $200 for an expedited passport. It could take migrants nearly half a year to recoup these costs.

The Broader Consequences of Increased Regulation

In other parts of the world, migration regulations similar to the Thai decree have often had unexpected consequences, as sociologists have documented. In the well-studied example of the U.S.-Mexico border, increased border securitization beginning in the 1990s transformed the pattern of Mexican migration to the United States from a largely circular dynamic to one of long-term settlement—an outcome that was neither intended nor desired by policymakers at the time.

What unanticipated consequences may arise in the wake of increased criminalization and regulation in Thailand? Most critically, more employers are likely to require workers to obtain documents, making migration more expensive for workers. This may change the incentive structure in ways that shape who moves, for how long, and with what results. For instance, prior research by the first author has suggested that there may be a tradeoff between highly regulated and “pro-poor” migration. In other words, where the worker-borne costs of migration are high and migration processes formalized, the poor may be less likely to participate in cross-border movement. Increased efforts to manage migration may therefore unwittingly constrain mobility options for the poor.

This effect may be particularly strong in Cambodia, where migrants primarily come from poor and low-income households. Research by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Cambodia suggests that most of these migrants would prefer to migrate legally, but are unable to do so given the high costs of such movement. Thus, if the barriers and costs increase significantly, migration may become even more difficult for poorer families. Alternately, migrants may benefit less from migration as they must use more of the money they earn to pay the high costs of recruitment or obtaining documents. Given the Cambodian government’s interest in migration as a poverty-reduction strategy, this is a key concern.

Similarly, as migration processes become formalized, it may become more difficult for migrants to move for short periods of time—incentivizing longer stays and new forms of settlement. There may also be broader social impacts. For instance, it is common for Cambodians to migrate with young children, as part of a family strategy to remain together. As movements become riskier and more expensive, families that once migrated together may begin to leave children in the care of relatives back in Cambodia.

In the context of persistent economic deprivation driving migration, these shifts may also push migrants toward riskier and more dangerous forms of crossing and/or employment opportunities, without significantly reducing flows. Again, lessons from the U.S.-Mexico context may be instructive. As U.S. border security increased, migrants began moving through more dangerous corridors, paying higher physical and economic costs.

A Changing Migration Landscape?

It is not yet clear what long-term impacts the changes in Thailand’s migration policies will have. Government officials have defended the decree by framing it as an anti-trafficking measure. To be sure, the imposition of a new fine for employers who confiscate the personal documents of migrant workers could limit migrant vulnerability. However, the remaining elements of the law—including the continuation of the practice of linking migrants’ status to their employers, and the ability of the government to require that foreign workers live in certain areas—do little to protect from exploitation. At the same time, as employers encourage workers to obtain documents, the law is creating new economic burdens which appear to be falling primarily on migrant workers.

Depending on its implementation, the new law may ultimately do little to fundamentally shift the informal, networked movements that have characterized the region for the past several decades. In this regard, prior laws introducing harsh penalties for migrant workers have not had much effect. Some critics have suggested irregular migration is so pervasive that the law will be nearly impossible to fully enforce. Moreover, if recent Thai history is any indication, the military government is likely to back down from any policy that seems to spark a worker exodus. However, considering the broader trend across Asia is one of increasing regulation and control over migration, it would not be surprising to see migration patterns in the region shift accordingly toward more regulated, high-cost forms of movement. Such a reshaping could have considerable impacts not only on who moves, but also on communities in host countries and at origin.

The Thai government’s chosen pathway toward expanded regulation and control is not the only way forward. In Southeast Asia more broadly, the trend toward increased criminalization of irregular migration is occurring alongside greater labor market integration for certain categories of highly skilled workers. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) model, which facilitates legal labor migration and provides greater freedom of movement within the region, serves as a useful alternative to the restrictive policy framework favored by the Thai government. Expanding these efforts further could address both the rights violations and vulnerabilities that unauthorized migrants experience, and alleviate the potential exclusions that come with increased regularization.

Thailand both needs and benefits from migrant labor. Meanwhile, Cambodia is quickly becoming a labor-exporting country, and communities now rely on remittances from relatives working in Thailand. If the Thai government makes good on its promise of zero tolerance for irregular migration, the costs of migration are likely to rise, fewer Cambodians may choose to work in Thailand, and poor households may be less able to supplement livelihoods through work abroad. These shifts have potentially stark consequences for poverty reduction, the physical and social well-being of migrant workers, and the Cambodian and Thai economies overall.

Sources

Bylander, Maryann. 2014. Borrowing Across Borders: Migration and Microcredit in Rural Cambodia. Development and Change 45 (2): 284-307.

---. 2015. Depending on the Sky: Environmental Distress and Coping in Rural Cambodia. International Migration 53 (5): 135-47.

---. 2017. Poor and on the Move: South-South Migration and Poverty in Cambodia. Migration Studies 5 (2): 237-66.

Dickson, Brett and Andrea Koenig. 2016. Assessment Report: Profile of Returned Cambodian Migrant Workers. Phnom Penh: International Organization for Migration Cambodia. Available online.

Gruß, Inga. 2017. The Emergence of the Temporary Migrant: Bureaucracies, Legality and Myanmar Migrants in Thailand. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 32 (1): 1-35.

Harkins, Benjamin and Meri Åhlberg. 2017. Access to Justice for Migrant Workers in South-East Asia. Bangkok: International Labor Organization.

Huguet, Jerrold W., ed. 2014. Thailand Migration Report 2014. Bangkok: UN Thematic Working Group on Migration in Thailand.

Huguet, Jerry, Aphichat Chamratrithirong, and Claudia Natali. 2012. Thailand at a Crossroads: Challenges and Opportunities in Leveraging Migration for Development. Bangkok and Washington, DC: International Organization for Migration and Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Kaur, Amarjit. 2010. Labour Migration in Southeast Asia: Migration Policies, Labour Exploitation and Regulation. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 15 (1): 6-19.

Kijewski, Leonie and Yon Sineat. 2017. Cambodian Migrant Workers Return from Thailand. Phnom Penh Post, July 6, 2017. Available online.

---. Voices from the Border. Phnom Penh Post, July 14, 2017. Available online.

Latt, Sai S.W. 2013. Managing Migration in the Greater Mekong Subregion: Regulation, Extra-legal Relation and Extortion. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 34: 40-56.

Lawreniuk, Sabina and Laurie Parsons. 2017. After the Exodus: Exploring Migrant Attitudes to Documentation, Brokerage and Employment Following the 2014 Mass Withdrawal of Cambodian Workers from Thailand. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 38 (3): 350-69.

Maltoni, Bruno. 2010. Analyzing the Impact of Remittances from Cambodian Migrant Workers in Thailand on Local Communities in Cambodia. Phnom Penh: International Organization for Migration.

Martin, Philip. 2007. The Economic Contribution of Migrant Workers to Thailand: Towards Policy Development. Bangkok: International Labor Organization. Available online.

Massey, Douglas, Jorge Durand, and Karen A. Pren. 2015. Border Enforcement and Return Migration of Undocumented Mexicans. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (7): 1015-40.

Mekong Migration Network (MMN). 2017. Safe from the Start: The Role of Countries of Origin in Protecting Migrant Workers. Chiang Mai, Thailand: MMN.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and Cambodia Development Resource Institute. 2017. Interrelations between Public Policies, Migration and Development in Cambodia. OECD Development Pathways Series. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online.

Pholphirul, Piriya and Pungpond Rukumnuaykit. 2010. Economic Contribution of Migrant Workers to Thailand. International Migration 48 (5): 172-202.

UN Action for Cooperation against Trafficking in Persons. 2015. Migration Experiences of Cambodian Workers Deported from Thailand in 2009, 2010, & 2012. Bangkok: UN Development Program. Available online.

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). 2016. Economic Targeting for Employment: A Study on the Drivers behind International Migration from Cambodia and the Domestic Labor Market. Washington, DC: USAID. Available online.

Xiang, Biao and Johan Lindquist. 2014. Migration Infrastructure. International Migration Review 48: S122-48.