You are here

Can Czechia Capitalize on High-Skilled Immigration amid Influx of Ukrainians?

A displaced Ukrainian in Prague. (Photo: © UNHCR/Michal Novotný)

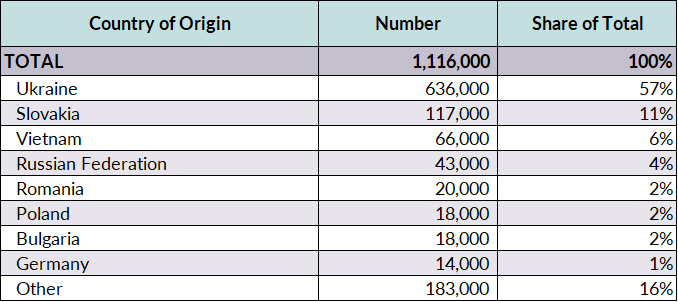

Czechia has rapidly shifted from a country of emigration to one of immigration, primarily as the result of the political and economic transitions coinciding with the end of communism in 1989. Today, it is a growing migrant destination in Central and Eastern Europe, including for many high-skilled migrants. The foreign-born population of Czechia (also known as the Czech Republic) has risen swiftly in recent years, and more than doubled from 2017 to 2022, partly because many people fled the war in Ukraine and conflict building up to Russia’s 2022 invasion. There were more than 1.1 million foreign nationals in Czechia at the end of 2022, according to the national statistical office, more than half of them from Ukraine; Czechia hosts the third largest number of displaced Ukrainians in the European Union, after Poland and Germany. Immigrants account for one-tenth of the country’s total population of 10.5 million people and are concentrated in cities such as Prague and Brno. According to the national statistical office, approximately 124,000 immigrants worked in jobs requiring a high level of skills as of 2020, and the numbers of highly skilled migrants have tripled over the past decade.

Highly skilled migrants, including many newly arrived Ukrainians, represent a potential major benefit to Czechia, which has undergone rapid economic growth since the transition from communism. On paper, the country looks very attractive. It has one of the lowest unemployment rates in the European Union (2.3 percent in December 2022) and fares well in the quality of opportunities for high-skilled workers, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) indicator, which accounts for qualification levels and employment. Since joining the European Union in 2004, Czechia has created different classifications for foreign workers from other EU Member States and those from outside the bloc. Many high-skilled migrants come from other EU Member States such as Slovakia or Poland (the origins of 117,000 and 18,000 immigrants in Czechia, respectively, at the end of 2022), meaning their qualifications are automatically recognized.

However, migrants from outside the European Union face lengthy visa processes before entry and even more red tape after settling in Czechia. The strenuous processes facing these third-country nationals might hinder them from realizing their full economic potential. This is likely the case for many Ukrainians, large numbers of whom had worked in Czechia even before the recent outbreak of full-scale war with Russia.

The arrival of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians marks a moment for Czechia to re-evaluate its policies and reconsider how it wants to incorporate immigrants into its economy, especially those with high levels of education. The future for many Ukrainians is uncertain, and the ease of their integration into Czechia will help determine how many stay in the country or leave, either to return to Ukraine or migrate elsewhere. Already, the new arrivals have prompted some changes that could benefit all high-skilled migrants, such as the creation of extra kindergarten places to relieve the pressures on working parents. However, the question remains whether Czechia will keep the momentum to ensure that the skills of all arrivals can be transferred.

Table 1. Immigrants in Czechia by Country of Origin, 2022

Note: Data are as of December 31, 2022.

Source: Czech Statistical Office, “Foreigners in the Czech Republic - Provisional Data - Quarterly; 2004/06–2022/12,” updated January 26, 2023, available online

This article analyzes the opportunities and challenges for immigration of well-educated individuals to Czechia. Based on research by the authors with migrants from Ukraine and other countries, it provides an overview of the situation of recent Ukrainian arrivals and the government’s policies over time. While the country has been selective in recent years about the types of immigrants it seeks to attract, it has not always been successful at integrating immigrants into Czech society, mirroring similar challenges faced by other countries.

Box 1. Methods and Definition

This article is based on the authors' research about high-skilled migrants living in Czechia. One yearlong project, conducted in 2022, included 53 interviews and 315 survey responses with immigrants who had completed tertiary education. Another ongoing research project involves high-skilled migrants from Ukraine who are holders of temporary protection.

The definition of high-skilled immigration varies. In this article it is used to refer to foreign-born individuals with tertiary education such as a college degree, or who are employed in a position involving a high level of specialized skill.

The Impact of the Ukraine Displacement Crisis

Nearly 496,000 displaced Ukrainians were registered for temporary protection in Czechia as of March, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). While the largest number of those displaced from Ukraine have gone to Poland, Czechia’s smaller overall population means that Ukrainians comprise a larger share of total population than in any other EU Member State. As of September 2022, nearly 6 percent of Czechia’s population was from Ukraine.

In general, displaced Ukrainians in Czechia are relatively well educated. Two-thirds of those who were economically active were high-skilled and working in specialist, technical, or managerial roles, according to a PAQ Research study released in September 2022. Yet only about half the displaced Ukrainians who had been economically active in Ukraine were employed in Czechia. About 15 percent were working remotely for Ukrainian employers (this was especially the case for Ukrainians residing in Prague). While some Ukrainians were out of the labor force because they are retired or caring for small children, others might have been unable to find work and may face serious consequences for months-long gaps in employment, including loss of income and degradation of skills. Moreover, of Ukrainians working in Czechia, just one-third worked in positions that matched their qualifications, while 44 percent worked in jobs below their skill level—a phenomenon known as “brain waste.”

This labor market mismatch could be a missed opportunity for Czechia. Educational attainment levels in Ukraine have risen since 1991, especially among women (56 percent of working-age women held a tertiary degree as of 2020, according to OECD, compared to 43 percent of men). In part because of war-time restrictions preventing many combat-eligible men from leaving Ukraine, highly educated women are over-represented among new Ukrainian arrivals in Czechia, and they tend to have higher qualifications than Ukrainians who have resided in Czechia since before the war. This situation represents both a significant challenge but also potential for future economic gains. New arrivals who stay outside the labor force for long or who suffer from an employment-education mismatch are less likely to be as economically productive as those who find jobs that demand their full set of qualifications.

A Labor Market Barrier

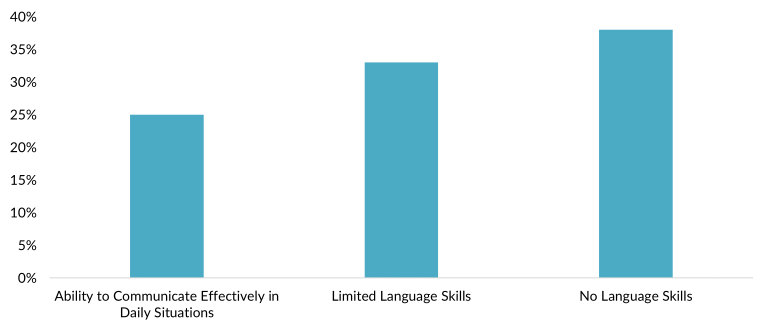

Language plays a major role in labor market integration. Just 25 percent of displaced Ukrainians in Czechia have the language skills necessary to communicate effectively in daily situations; one-third can say only a few sentences in Czech; and 38 percent do not speak the language at all. Language courses offer one remedy, but migrants face obstacles. One is financial, as many Ukrainians cannot afford to pay for courses, although 78 percent say they would like to attend classes if their employer covered the cost, according to PAQ Research. Another is time: Many people do not have enough time to learn Czech because they are working, even though knowledge of the language could provide access to more skilled and higher-paying positions.

Figure 1. Czech Language Skills of Displaced Ukrainians in Czechia, 2022

Source: Martina Kavanová, Daniel Prokop, Michael Škvrňák, and Matyáš Levinský, Hlas Ukrajinců: Pracovní uplatnění, dovednosti a kvalifikace uprchlíků (Prague: PAQ Research, 2022), available online.

Full utilization of an individual’s skills and knowledge of the Czech language both are crucial for finding a well-paying job. To support this language acquisition, employers might consider supporting employees by paying for courses or adjusting schedules so workers can attend. While free language courses are offered by the state’s integration centers for foreigners (CPIC), there are long waiting lists and many courses take place at times that are inconvenient for working people or those looking for a job. Nongovernmental organizations also provide some courses, but they are unable to meet the large demand.

Czechia’s Policies Towards High-Skilled Migration

As countries in Central and Eastern Europe are experiencing population loss, Czechia’s population would be declining were it not for immigration. Particularly since the country joined the European Union in 2004, the government has sought to pivot towards encouraging migrants who would grow the economy. Ukrainians and others have come to a country that has increasingly been interested in capitalizing on migrants. However, many high-skilled arrivals have worked in positions below their skill levels.

In part, the country’s aims reflect its status as a bridge between Central and Eastern Europe. Researchers have tended to describe Czechia’s approach towards high-skilled immigration as contingent on the European Union’s policies and economic situation. While Czechia has suffered brain drain in professions including health care and research, this loss is not as severe as in other regional states such as Poland or Slovakia. Czechia is likely to compete with other states in Central and Eastern Europe on attracting foreign talent, and not so much with countries farther west, such as the United Kingdom or United States. Still, some migrants might view Czechia as a stepping-stone to higher-income EU Member States such as Germany.

Czechia has implemented policies and programs to attract highly skilled professionals and boost the country’s innovation and competitiveness. The first pilot program to attract certain high-skilled migrants started in 2003 and was extended, although it became less attractive after the economic downturn in 2008. At this time, Czechia was also reluctant to accept more foreigners, so it attempted to reduce the numbers offered residence permits (known as green cards until 2014, and since then replaced by so-called employee cards). Around the same time, the European Union introduced Blue Cards for high-skilled workers from outside the bloc, but they never became the main point of entry for well-educated immigrants in Czechia, who tended to come through other visa schemes (many also come through non-labor-related routes, such as family reunification).

The government has introduced a “fast-track” visa program for highly skilled workers from certain countries such as Mongolia, the Philippines, Serbia, and Ukraine, enabling them to obtain work permits and legal residency in a short amount of time. However, people must be outside of Czechia to apply for this program and have secured employment before their arrival. The program has also been criticized for lengthy application processes at embassies and waits for appointments that have stretched for several months. Since the process is not very straightforward, there are several private agencies and businesses that work as intermediaries both in migrants’ countries of origin and in Czechia.

Compared to previous years, Czech immigration policies have become more selective, at times in ways that might undercut its larger goals. The government has attempted to regulate the number of arrivals by setting per-country quotas for economic migrants. However, this would seem counterintuitive, as it limits the numbers of high-skilled immigrants who might keep the Czech economy competitive and whom the government has otherwise sought to encourage. So far, the arrival of new Ukrainians has led to wider debate about the length and difficulty of recognizing skills, credentials such as diplomas, and work experience in certain professions, and there have been calls to simplify the process.

Integration of High-Skilled Migrants

The authors’ research shows that the longer high-skilled migrants stay in Czechia the more likely they are to intend to remain. For the government, this presents the challenge of how to better retain migrants who have only been in the country for a short amount of time—a question that is especially relevant as displaced Ukrainians contemplate their future in Czechia. While personal factors are difficult for the state to influence, there are certain practices it can take to increase migrant integration, such as encouraging language learning and quick recognition of qualifications, which contribute to immigrants’ wellbeing and their ability to contribute fully to their new society.

According to the research, immigrants in Czechia sometimes experience a so-called integration paradox, when those who are highly educated and structurally integrated turn away from the host country culture. A key factor why these immigrants might not feel part of Czech society, despite fully speaking the language and meeting other benchmarks, might be that many cannot find friends with the same level of education, knowledge, and experience. Another important factor is finding a sense of purpose within society. This is often connected with being able to continue in one’s field of expertise and having their qualifications recognized. In other words, one determinant of successful integration is having a good job and a healthy financial situation; another is the feeling of belonging to the new society.

One woman from the United States explained this feeling: “I have a job at the local school, so I am now a part of the community. I’m serving the community. I’m teaching their kids, they’re teaching my kids—that was the key for me. And now it feels like home.”

Another way of understanding this challenge is the relatively low level of immigrants’ political participation, as measured through trends in voting, the government’s consultation of immigrant leaders, and the existence of migrant organizations. This is also connected with knowledge of the Czech language and information campaigns targeting the foreign born. As a man also from the United States claimed, “I think that if you don’t learn the language, you’ll never integrate.”

Displaced Ukrainians told the authors in 2022 they were generally still unsure whether they would stay in Czechia long term. Key in their answers was the region or city where they were from and the extent to which it had been destroyed by war.

But there were other issues, too. Young people said they preferred to stay in Czechia since they did not see a future in their war-ravaged country and considered studying at universities or finding a job. Respondents often also mentioned better living conditions in Czech cities, including better infrastructure, parks, and safety for children and women.

“It’s clean here, there are flowers,” one Ukrainian woman said. “I’m from an industrial area; when I open the window, there’s bad air. Here’s the blue sky.” Another Ukrainian woman said that, regarding safety in Czechia, “I am not afraid here because there is lighting [in the streets] and I am not afraid to go out as a woman in the evening.”

Older respondents, however, said they wanted to return to join their families or spouses still in Ukraine, and cited challenges such as learning the Czech language or homesickness. Others were still unsure whether or not to stay. “My heart and soul wants to return, but the conditions are better in the Czech Republic,” said another Ukrainian woman.

The younger Ukrainians preferring to stay in Czechia represent an opportunity for the country. Yet it is up to the government to maximize ways to transfer educational credits for those still in school and recognize graduates’ academic qualifications. There already are glimmers of hope in some professions, such as health care, where displaced Ukrainians can work in lower-level positions, receive on-the-job training, and learn Czech as they wait for their credentials to be recognized and hope for quick advancement. Another example is teaching assistants who started working with displaced Ukrainian children as needed; while many of these assistants were highly skilled, a high school certificate was sufficient for them to begin their jobs. Other industries might consider introducing combined language and on-the-job training for positions where the knowledge of another language, such as English, is insufficient.

The Future of High-Skilled Migration

In Czechia, high-skilled immigration has become increasingly important due to the country’s growing economy, strong job market, and the presence of many international companies. High-skilled immigration can bring economic benefits, the transfer of knowledge and skills, and can also help offset the effects of population aging by bringing in younger and skilled workers.

For high-skilled immigrants to stay, however, they also must feel a sense of belonging and that they are contributing to the host society. This can be done through language training and swiftly recognizing their academic and professional qualifications.

Czechia’s political transition to democracy and alignment with the West has been accompanied by its transition from a country of emigration to one of immigration. To continue moving in this direction, the Czech labor market needs skilled migrants to supplement the domestic labor force. The foreign born are becoming a part of Czech society in many places, especially bigger cities that host universities, research centers, and international companies.

As hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians settle in for the long term, it will be especially important to ensure that they are able to integrate in ways that benefit them, their families, and Czech society as a whole. Emphasizing that they learn the Czech language—and making it easy and inexpensive for them to do so—would help accomplish this goal. So would ensuring that immigrants find employment appropriate to their skill level. The benefits of fully integrating these individuals into Czechia would be felt by everyone.

Sources

Czech Statistical Office. 2021. Počet v Česku pracujících cizinců loni vzrostl. Updated December 13, 2021. Available online.

---. 2023. Data on Number of Foreigners. Updated January 26, 2023. Available online.

Drbohlav, Dušan and Kristýna Janurová. 2019. Migration and Integration in Czechia: Policy Advances and the Hand Brake of Populism. Migration Information Source, June 6, 2019. Available online.

European Commission. 2022. Czech Republic: Updated Policy for the Integration of Foreigners in 2022. March 28, 2022. Available online.

Eurostat. 2023. Unemployment Statistics. Updated February 1, 2023. Available online.

Kavanová, Martina, Daniel Prokop, Michael Škvrňák, and Matyáš Levinský. 2022. Hlas Ukrajinců: Pracovní uplatnění, dovednosti a kvalifikace uprchlíků. Prague: PAQ Research. Available online.

Migrant Integration Policy Index. N.d. Czechia: Key Findings. Accessed March 1, 2023. Available online.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2023. What We Know about the Skills and Early Labour Market Outcomes of Refugees from Ukraine. January 6, 2023. Available online.

Parliament of Czechia. 2022. 278/0: Chamber of Deputies. Prague: Parliament of Czechia. Available online.

Prokop, Daniel et al. 2023. Hlas Ukrajinců: Práce, bydlení, chudoba a znalost češtiny. Výzkum mezi uprchlíky. Prague: PAQ Research. Available online.

Tuccio, Michele. 2019. Measuring and Assessing Talent Attractiveness in OECD Countries. Social, Employment, and Migration Working Paper No. 229, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Paris, May 2019. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023. Operational Data Portal: Ukraine Refugee Situation. Updated March 14, 2023. Available online.