You are here

Despite Trump Invitation to Stop Taking Refugees, Red and Blue States Alike Endorse Resettlement

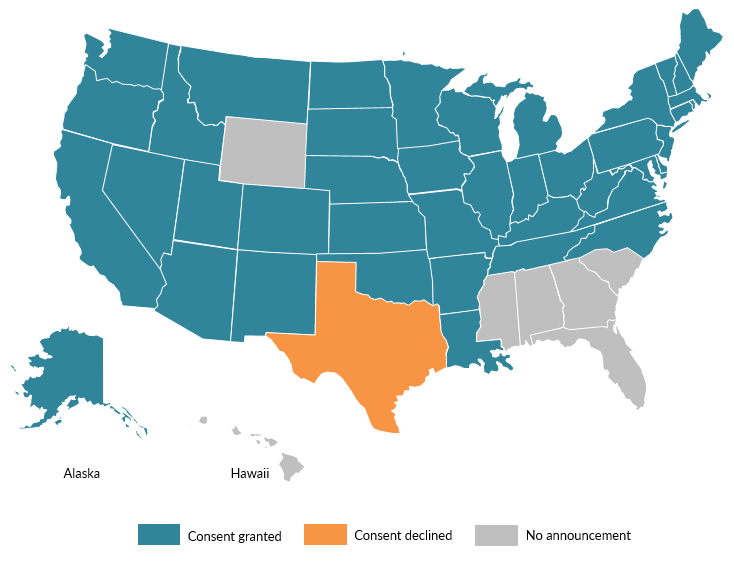

Forty-two states have affirmed their consent to accept new refugees. (Map: Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service)

Sidestepping an opportunity from the Trump administration to stop accepting refugees, the vast majority of U.S. governors, Republican and Democrat alike, have affirmed their support for continued refugee resettlement. This resounding endorsement from governors and mayors of communities across the United States, amid the record-low resettlement permitted by the administration since 2017, suggests there may be limits to the Trump agenda when it comes to refugees.

On September 26, 2019, President Donald Trump issued an executive order that requires state and local elected leaders to affirmatively opt in if they wish to receive newly arriving refugees—the only time they have been given an opportunity to do so. The executive order marked the latest effort by the White House to restrict the U.S. refugee resettlement program, following a temporary freeze on all resettlement in 2017 and then a drastic reduction in admissions. The president set the refugee ceiling at 18,000 for this fiscal year, a sharp drop from the 110,000 level set at the end of the Obama administration—and by far the lowest allocation in the history of the resettlement program.

Forty-two states (including 19 Republican-led) and more than 100 mayors announced they would continue to host refugees—a move that reportedly caught the White House by surprise. The governor of Utah, Gary Herbert, even asked the administration to increase refugee resettlement in his state: “[W]e empathize deeply with individuals and groups who have been forced from their homes and we love giving them a new home and a new life."

Figure 1. Refugee Resettlement Consent Announcements by State, January 2020

Source: Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service (LIRS), “Latest Developments on Refugee Resettlement Consent,” January 2, 2020, available online.

Texas, whose governor argued that the state was overburdened by an asylum crisis on its southern border, so far has been the only exception. (The governor’s decision drew swift backlash, especially from mayors and county leaders of all of Texas’s largest cities, including Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, and Austin.)

In a further rebuke to the administration, a federal court in Maryland on January 15 preliminarily blocked the executive order from going into effect, ruling that it would essentially give state and local governments “veto power” over refugee resettlement, and thus would be a violation of the Refugee Act of 1980. The judge also said bringing subnational governments into the resettlement decision was “inherently susceptible to hidden bias.”

The preliminary injunction could be stayed or overturned on appeal, thus humanitarian protection and immigrant-rights groups are continuing to press states and localities to declare their intent to remain in a program that has successfully provided a home to millions of foreign nationals fleeing persecution.

Historic Commitment to Refugees

The United States, a country founded on the principle of providing refuge, has historically led the world in absolute numbers of refugees resettled. Between the end of World War II and 1980, when the U.S. resettlement program was formally created, the country opened its doors to approximately 1.5 million refugees. Since 1980, the United States has admitted 3.1 million refugees—and more annually than any other country until 2018. Even as recently as 2016, the United States accepted two-thirds of all refugees resettled worldwide. When viewed per capita, however, a number of other countries admit more refugees.

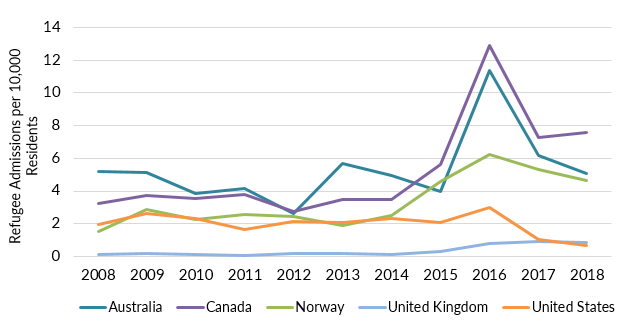

Figure 2. Refugee Resettlement Per Capita for Selected Countries, 2008-2018

Sources: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) calculations, using refugee resettlement data from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Population Statistics,” available online; country population data from the World Bank, “Population, total,” available online; all data accessed January 21, 2020.

Refugee resettlement, whether by the United States or other countries, encompasses just a tiny percentage of the total number worldwide who need protection. For example, when the United States admitted a recent high of 84,995 refugees in 2016, this represented just 0.4 percent of the 22.5 million refugees registered with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) worldwide that year.

The U.S. share of overall resettlement is sure to drop, as the U.S. resettlement program has been sharply cut since January 2017. And in 2018, for the first time since establishing its refugee program, the United States did not lead the world in resettlement. Canada resettled 28,000 refugees in 2018, compared to U.S. resettlement of 23,000.

This drop was precipitated by the Trump administration’s systematic efforts to scale back the program. In June 2017, Trump first temporarily suspended refugee admissions and then cut the refugee ceiling set by his predecessor, Barack Obama, from 110,000 to 50,000. In fiscal years (FY) 2018, 2019, and 2020, the administration lowered the ceiling even further, from 45,000 to 30,000, and to 18,000. The administration also limited the number of refugees entering by slowing down admissions through enhanced security measures and a lack of adequate staffing. Even though the FY 2018 ceiling was set at 45,000, for example, just 22,291 refugees were ultimately admitted.

The administration has also significantly changed the make-up of admissions, with an 87 percent drop in the number of Muslim refugees admitted since FY 2016. This decline has largely been driven by limited arrivals from 11 countries the administration designated as “high risk”: Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Mali, North Korea, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. Since January 2018, applicants from these countries have been subjected to extra screening measures.

Suspicion of Refugee Resettlement Resurfaces

Even before Trump took office, there was growing evidence of opposition to resettlement in some parts of the country, especially in moments of heightened concern over national security such as the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. In 2015, high-profile terrorist attacks in European capitals—not perpetrated by refugees but blamed on terrorists who in some cases slipped into the flows of refugees and economic migrants fleeing war-torn Syria and other places—prompted 31 U.S. governors to issue statements opposing the resettlement of Syrian refugees in their states.

These statements spurred debate about states’ authority in the refugee resettlement process. Historically, states have had no control over whether and which refugees have been settled in their territory. All they could do was withdraw from administering the program themselves. Under a provision authorized by Congress in 1984 (named Wilson-Fish after then Senator Pete Wilson and Congressman Hamilton Fish), if a state declines to administer refugee resettlement, the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement may select one or more voluntary organizations within the state to manage the federal funding for assistance and social services provided to eligible refugee populations. Twelve states currently have Wilson-Fish programs: Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Nevada, North Dakota, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Vermont.

In the wake of terror attacks in Paris and elsewhere in 2015, several states tried to assert their authority over resettlement by suing in federal court. In separate lawsuits, Texas and Alabama tried to stop placement of refugees in their states until the federal government had consulted them. Then-Indiana Governor Mike Pence tried a different tactic: attempting to block the resettlement of Syrian refugees by refusing to reimburse resettlement organizations that assist such refugees. These efforts were stricken down by federal courts, which ruled that under the Refugee Act of 1980 states cannot sue the federal government and that federal law forbids discrimination in federally funded programs on the basis of national origin.

Executive Order on Enhancing State and Local Involvement in Refugee Resettlement

Tapping into the states’ rights debate on refugees while on the campaign trail in 2016, Donald Trump vowed to allow states and localities more say on which, if any, refugees they received. While his September 2019 executive order was an attempt to fulfill that promise, it cannot block refugees from moving to nonparticipating states or localities after their initial resettlement. The order would prevent refugees from being placed initially in nonparticipating states and, as a result, such locations would not receive federal funds to assist with refugee integration. Thus, in the end, the order could strain nonparticipating jurisdictions by making it more difficult for new arrivals to become self-sufficient.

In blocking the executive order, U.S. District Judge Peter Messitte in Maryland found that, regardless of the results, it would violate federal law by empowering states and localities with this decision. While the government had tried to frame the order as enhancing a consultation process that is already required under the statute, the judge flatly rejected this reasoning, saying it bordered on “Orwellian newspeak” and that the change “flies in the face of clear congressional intent.” In addition, Messitte found the order may be unconstitutional because the constitution specifies that the power to admit or exclude noncitizens is “exclusively” federal in nature. Finally, the judge raised concerns under the Administrative Procedure Act, finding that the government failed to adequately consider critical factors when creating the policy, including what would happen if after initial placement refugees moved to nonparticipating locations.

Thus, as with the three prior federal court decisions described above, the judge found that states and localities do not have the authority to block federal resettlement decisions.

Lasting Impact: Starving Resettlement Infrastructure

Whether or not the ruling is ultimately overturned, resettlement is already more challenging in many communities as a result of the weakening of the network of resettlement agencies.

Nine voluntary agencies have been central to the resettlement program and its successes. But because of decreasing arrivals since 2017, these agencies have been forced to shutter more and more offices each year. As of June 2019, refugee resettlement agencies had closed 51 programs and suspended resettlement services in 41 offices across 23 states. And more will be closing. Should the September 2019 executive order go back into effect, the State Department could refuse to renew existing contracts with resettlement groups if they are working in states or localities that fail to opt in.

These reductions have meant serious cuts to personnel, losing valuable expertise on issues important for successful resettlement, including trauma care, housing assistance, and job placement. Even if a future administration sought to reverse the current refugee admissions policy, the damage done to the U.S. resettlement program’s infrastructure will be hard to repair.

The U.S. resettlement network has been critical to the success of resettled refugees. Designed to help refugees achieve rapid economic self-sufficiency and social integration, the resettlement program emphasizes effective labor force engagement. In fact, Migration Policy Institute (MPI) research found that for most socioeconomic integration indicators, refugees are quite successful over time. For example, MPI found that refugee men had a higher employment rate than U.S.-born men, while refugee women and U.S.-born women had identical employment rates. And refugees fair particularly well in Texas. In a study examining five distinct groups of refugees in four refugee-receiving states, including Texas, MPI experts found refugees in Texas to be employed at higher rates and have higher relative incomes than refugees in other states and in the United States overall.

These well-established contributions were not lost on the states and localities that have opted to continue to accept refugees. They were lobbied by a variety of stakeholders, including local business leaders who rely on refugees for their workforce, evangelical leaders, and others. This display of a deep commitment to refugees will perhaps allow more political space for resettlement should this or future administrations increase the level of admissions.

Resources

- Executive Order 13888, Enhancing State and Local Involvement in Refugee Resettlement

- Memorandum opinion in HIAS Inc. v. Donald J. Trump

- MPI commentary on the changes to refugee flows under the Trump administration

- MPI article on rising opposition to Syrian refugee resettlement in 2016

- MPI report on integration outcomes for refugees in specific states

- MPI report on the integration outcomes of U.S. refugees by national origins

- MPI data tool on U.S. refugee admissions and annual resettlement ceilings from 1980 to present

- Description of the Wilson-Fish model

- Refugee Council USA report on cuts to refugee resettlement

National Policy Beat in Brief

Supreme Court Allows Administration to Implement Public-Charge Regulation, Pending Resolution of Litigation. On January 27, a divided Supreme Court allowed the Trump administration to move forward its public-charge regulation. The ruling, which came by a 5-4 vote, reversed the final of four nationwide injunctions initially placed on the public-charge rule by judges across the country. An injunction against the rule’s enforcement in Illinois remains in effect.

The rule gives the federal government broad discretion to deny admission to would-be immigrants or to withhold legal permanent residence or temporary nonimmigrant statuses from foreign nationals already in the United States on the grounds that they are using government benefits or are likely to do so in the future. Experts at the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) found that 69 percent of recent immigrants had at least one negative factor under the administration’s expanded test, indicating implementation of this rule could significantly reshape legal immigration.

- Supreme Court order staying the lower court injunction in New York v. DHS

- Final U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services rule, Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds

- MPI commentary on the potential impact of the public charge-rule

- CNN article on the Supreme Court ruling

State Department Issues Rule to Prevent “Birth Tourism.” On January 24, the State Department issued a final regulation that attempts to prevent foreign nationals from coming to the United States to give birth. The regulation explicitly states that coming into the United States strictly for the purpose of obtaining U.S. citizenship for a child by giving birth in the country, a practice dubbed birth tourism, is not a permissible purpose for receiving a B-2 visitor visa.

It is not known how widespread the practice of birth tourism is, but the federal Centers for Disease Control reported in 2017 that 9,254 children were born in the United States to foreign national mothers who normally reside outside of the country. In recent years, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has raided locations in California where businesses put up women, often Chinese or Russian, during the latter stages of their pregnancies.

Although birth tourism was already considered an impermissible reason to obtain the B-2 visa, critics argue the regulation could cause women of child-bearing years to be subject to difficult questions during the consular interview process, and result in the exclusion of some. Others question the feasibility of enforcement, noting that the B-2 visitor visa is often issued for a period of ten years.

- Final rule, Visas: Temporary Visitors for Business or Pleasure

- Wall Street Journal article on the new regulation

DHS Presses Forward with Asylum Cooperation Agreements. In November, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) began deporting asylum seekers to Guatemala under an asylum cooperation agreement (ACA) signed with the Guatemalan government last July. Under this agreement, migrants from countries other than Guatemala who apply for asylum at the U.S. southern border can be deported to Guatemala to seek protection there instead. So far, the United States has sent more than 300 migrants from Honduras and El Salvador, including many children, to Guatemala. There was some confusion as to whether Mexican asylum seekers would also be sent to Guatemala, but outgoing Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales clarified that his government had not agreed to accept Mexican nationals.

The United States has signed similar deals with Honduras and El Salvador, though these have yet to take effect. Earlier this month, Homeland Security Acting Secretary Chad Wolf said he expected implementation of the Honduran agreement to start in the coming weeks.

On January 15, the American Civil Liberties Union and several other groups filed a lawsuit trying to block the administration from enforcing the ACAs with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. The groups argue that the three Central American countries fail to meet the standard of providing asylum seekers with “access to a full and fair procedure” required under U.S. law.

- CBS News article on the implementation of the asylum cooperation agreement with Guatemala

- AP article about the implementation of the deal with Honduras

- U.S. News & World Report article on Guatemala’s refusal to accept Mexican asylum seekers

- Complaint in U.T. v. William Barr

Appeals Court Allows Administration Access to More Funds for Border Wall. A three-judge panel of the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals lifted a district court’s permanent injunction blocking the use of $3.6 billion in Defense Department funds for construction of a border wall. The administration’s access to the funds was initially blocked by a federal judge in El Paso who found it unlawful for the government to use funds appropriated by Congress for a different purpose. In a short opinion, the Fifth Circuit panel stayed the injunction, reasoning that the plaintiffs likely lacked standing to sue. The lawsuit was brought by El Paso County and a civil- and immigrant-rights organization, Border Network for Human Rights.

The administration originally tried to reroute the funds in February 2019, following a budget standoff with Congress and a partial government shutdown. President Trump ordered $3.1 billion in additional funds to build the wall be transferred from counterdrug activities and a Treasury Department fund for forfeitures, and he declared a national emergency to access $3.6 billion from military construction projects. The administration’s transfer had also faced an injunction in the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, but the Supreme Court ultimately lifted the injunction.

- Order before the Fifth Circuit lifting the injunction in El Paso County v. Trump

- Memorandum opinion granting a permanent injunction at the district court level in El Paso County v. Trump

- Politico article on the Fifth Circuit’s order

Judge Allows Administration to Continue Separating Families “For Cause.” A federal district judge in California ruled on January 13 that the Trump administration is within its authority to separate families at the southern border, so long as it is doing so for legally permissible reasons. The judge, who halted the general practice of family separation in June 2018, found no evidence that the government is abusing its discretion to separate families in limited cases. These include instances where officials have cause to believe the adults traveling with a child are not the parents, or in circumstances including concerns about parents’ criminal history, communicable diseases, or parental fitness. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) had asked U.S. District Court Judge Dana Sabraw to rule on whether the 911 family separations that occurred after his June 2018 ruling were justified.

In his Ms. L v. ICE ruling, Sabraw ordered that if the government is separating families because of doubts about parentage, it must first use DNA tests to establish the adult is not the child’s parent.

Sabraw’s original ruling came amid massive national and international outcry over the Trump administration’s widespread separation of families during May and June 2018, at the direction of the president, who eventually ended the practice through an executive order. Officials recently concluded that a total of 4,368 children were separated under the administration’s policies.

- Order granting in part and denying in part motion to enforce preliminary injunction in Ms. L. v. ICE

- AP article on the decision

ICE Resumes Deportation Flights to Mexico’s Interior. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) announced it is resuming its Interior Repatriation Initiative with the Mexican government. Under this initiative, Mexican nationals who are inadmissible or who have been issued deportation orders are transported to the interior of Mexico, to their cities of origin, rather than just across the border. The initiative started in 1996 with the goal of making it harder for individuals to seek to attempt a further migration and to break the relationship between migrant and smuggler; it has been used inconsistently since then. ICE officials said the agency expects to return about 250 migrants weekly under the initiative, which has long been controversial in Mexico.

- ICE press release about the resumption of deportation flights

- FOX News article on the returns

Temporary Protected Status Extended for Yemenis and Somalians. DHS announced the extension of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) through September 2021 for certain nationals of Yemen and Somalia living in the United States. It did not redesignate either country for TPS, meaning only those Yeminis who have resided in the United States since January 2017 and Somalis resident since May 2012 qualify.

TPS was created in 1990 and provides work authorization and protection from deportation to certain nationals of countries that have been deemed unsafe for repatriation due to ongoing armed conflict, the effects of a natural disaster, or other circumstances. The program received a great amount of attention after the Trump administration tried to end TPS for nationals of El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, and Sudan. The terminations were challenged in multiple federal courts. The TPS terminations have been placed on hold pending the conclusion of the litigation.

- USCIS information page on TPS for Somalia

- USCIS information page on TPS for Yemen

- MPI article on TPS

State Policy Beat in Brief

New York Begins Implementing Law That Allows Unauthorized Immigrants to Apply for Driver’s Licenses. Under the recently enacted Green Light Law, New York since December has allowed all residents to apply for driver’s licenses, regardless of their immigration status. The law includes a provision prohibiting state motor vehicle officials from providing any license data to entities that enforce immigration laws. This has led the state to cut off database access to at least three federal agencies.

Less than a month after the enactment of the New York law, Homeland Security Acting Secretary Chad Wolf requested a department-wide study on how such laws affect DHS’s ability to enforce immigration, human-trafficking, drug-smuggling, and counterterrorism efforts. New York was the 13th state to authorize unauthorized immigrants to apply for licenses, and most of the other states also restrict data sharing.

- Text of the Driver's License Access and Privacy Act

- USA Today article on the New York law

- NBC News article on the DHS department study

Trump Administration Takes Aim at New York City’s “Sanctuary” Policies. Following the recent arrest of a Guyanese immigrant charged with raping and murdering a 92-year-old woman in Queens, the Trump administration has challenged New York City’s “sanctuary” policies. At a news conference in Manhattan on January 17, ICE Acting Director Matthew Albence accused the city of failing to comply with a request from his agency to detain the immigrant when he was arrested months earlier on an unrelated charge. The New York City Police Department claimed it never received the detainer request, but would not have complied in any event. New York City’s law on immigration detainers mandates that officials turn over to ICE only those noncitizens convicted of certain violent and serious offenses, and only if ICE requests the transfer with an official judicial warrant. An ICE press release published shortly after the accused’s arrest called the city’s policies “dangerously flawed.”

In an attempt to keep continued pressure on city officials, ICE issued four immigration subpoenas, demanding information on inmates wanted for deportation, including the Guyanese migrant at the center of this controversy. This happened days after ICE sent similar subpoenas to the City of Denver. City officials in Denver said they would not comply with the subpoenas, viewing them as “an effort to intimidate officers into helping enforce civil immigration law.”

- ICE news release on the detainer issued against the Guyanese national

- ICE news release on the immigration subpoenas

- New York Times article on the mounting standoff

- New York Daily News article on ICE’s issuance of subpoenas

Chicago Approves New Protections for Migrants. The Chicago City Council approved an ordinance that further limits the cooperation or data sharing city agencies can provide federal immigration agents. The ordinance also requires the Chicago Police Department to record and document any instances in which federal immigration officials request assistance. The new law still allows the police department to assist federal immigration authorities in cases involving noncitizens convicted of felonies.

- WTTV Radio article on the Chicago ordinance

California Appeals Court Rules Charter Cities Must Abide by State Sanctuary Law. On January 10, a three-judge panel in the California Appellate Courts overturned a lower court ruling that allowed charter cities to not abide by the California Values Act of 2017. The state law limits local cooperation with federal immigration enforcement. The Huntington Beach City Council had argued that the city does not have to abide by the law because it is a charter city and, as such, has more authority to impose local ordinances that may supersede state laws. The appellate panel disagreed, holding that the state law also applies to charter cities because it addresses “matters of statewide concern, including public safety and health.”

- LA Times article on the state appeals court ruling