You are here

Digital Litter: The Downside of Using Technology to Help Refugees

Digital litter is a hassle for everyday citizens, but can be harmful for migrants and refugees. (Art: Ryan Bergal)

Digital innovation has been one of the defining responses to record global humanitarian displacement and particular crises, such as the European refugee and migration crisis in 2015-16. In the past several years, the imagery of the smartphone-wielding asylum seeker has spurred countless policy reports, funding streams, and hackathons—as well as a new generation of apps to help newcomers navigate ocean and land crossings or connect with enthusiastic volunteers. These initiatives have rightly been celebrated for their desire to improve access to information and services for refugees—think of the creation, seemingly overnight, in Europe of Refugees Welcome (the so-called Airbnb for refugees) or coding schools for refugees. But in some cases, creativity has come at the expense of sustainability, with damaging consequences when information is outdated or outright incorrect.

Poor-quality information spread online or through digital tools, apps, and social media is undermining refugee and migrant decision-making and placing them in harm’s way. Dozens of clearinghouses, online maps, and platforms purporting to consolidate educational and other opportunities for refugees are now full of broken hyperlinks or touting things that no longer exist. Jobs websites, for example, set up at the height of the European migration crisis contain only a handful of old jobs. People on the move rely on accurate information to plan journeys, understand how to comply with visa and enforcement rules, identify legal channels for migration, get information about legal and working rights, and access vital services. Without this, they are more likely to fall prey to smugglers, choose illegal and disorderly channels, or end up working in the informal economy.

“Ghost” websites, outdated information, and broken links can be thought of as the “digital litter” of the Internet. Technologists describe the growing problem of “link rot,” when URLs end with a “page not found” or “404 error” message when content is renamed, moved, or deleted. This phenomenon is a hassle for everyday citizens and can make it hard for archivists and scholars to do their jobs. But this link rot, alongside dormant websites or apps that give the misleading impression of still being updated, is explicitly harmful for vulnerable migrants and refugees. Digital litter could mean someone wasting hours in an internet rabbit hole looking for information on refugee-specific scholarships or education courses no longer on offer. It could mean applying for jobs that no longer exist. At worst, it could mean embarking on a dangerous migration journey based on incorrect visa or asylum information.

The Importance of Information for Migration Movements

Research in recent years has revealed the importance of digital technology to refugees in planning journeys and identifying safe pathways. Migrants and refugees often trust information provided through social media rather than official resources such as government websites. Migrants use WhatsApp groups to find out where to go and adjust their routes in transit, they use GPS software on phones to plan routes or initiate rescues at sea, and they use Facebook to keep in touch with family and friends. Access to a smartphone and the digital infrastructure of wifi, simcards, charging docks, and electricity has been described as a literal lifeline.

But access to smartphones and the internet has brought a greater risk of misinformation. A 2016 study by Open University and France Médias Monde, led by Marie Gillespie and Claire Marous Guivarch, found that refugees seeking to reach Europe were exposed to a great deal of inaccurate information, including false rumors and conspiracy theories, via social media networks, and that this can make them more vulnerable to exploitation or physical harm during transit. Scholars of digital information and refugees often speak of “information precarity:” refugees are both more dependent on high-quality information and less likely to be able to access it, because of more limited internet access, language barriers, or low digital literacy. Crucially, refugees may be proficient at using social media to keep in touch with family and friends but lack the ability to differentiate between high- and low-quality information.

While a reliance on social media can be perilous, information on government websites is often confusing, and rarely available in different languages. Some governments may be reluctant to simplify information about asylum and immigration processes because they think such complexity acts as a deterrent to those who would abuse the system. Refugees with experience of being persecuted by their own governments may also distrust official sources. According to a 2017 WPP study, many refugees prefer to receive information through trusted social media groups and from personal networks. But others lamented the difficulty accessing straightforward information from government websites on simple questions such as “Am I allowed to work?”

The Spread of Digital Litter and the Dark Side of Civic Tech

The impetus to offer better organized, authoritative information for refugees represents, somewhat ironically, one factor behind the spread of digital litter. During the height of the European migration and refugee crisis, hundreds of apps and digital platforms were created to consolidate all opportunities in one place. Many of these were developed by tech startups interested in user-centered design and convinced they could offer a more slick, interactive way of conveying information, more along the lines of a TripAdvisor or Facebook than a static website. Others were optimistic about technology’s potential to solve refugee protection and integration challenges, for instance through language training apps or digital platforms for matching newcomers with people offering goods and services.

Much of the enthusiasm for tech solutions in the wake of the European crisis quickly fizzled out: some tech startups tried to reinvent the wheel or designed apps without enough attention to privacy and security issues. Others lost funding and folded. One particular problem was a proliferation of apps whose whole raison d’être was to be the “default” one-stop shop for refugees, for instancing by consolidating information about local services or job opportunities. Still, with so much overall duplication, no platform reached the critical mass of users, as the work of Ben Mason at betterplace lab has continuously pointed out. According to betterplace tracking, most of the 169 civic tech projects for refugees launched in 2015 and 2016 had become inactive as of July 2018.

But many of these offline deaths did not receive the online burial they needed. One of the biggest platforms designed to help migrants and refugees navigate complex admissions systems, Migreat, folded in 2016 because of funding issues. Its website—full of old but undated information with no message that it was no longer being updated—lingered for years, a ghost of its former self. (Today, the Migreat domain bounces to an online software vendor.)

Similarly, several German jobsites could send the misleading message that there are few jobs on offer in a country with a humming labor market. At this writing, Jobs4Refugees listed ten jobs across Germany; Careers4Refugees had 22 job postings, only one of which was posted in the last month. Workeer, which describes itself as the “largest job market for job-seeking refugees and interested employers” and whose founders were nominated for the Forbes Under 30 list in 2017, no longer has a functioning team, yet continues to list 36 jobs on its German-language website.

Inactive and underupdated websites are more than messy residue. By not signposting that they are no longer being maintained, or have fallen into disuse, they become explicitly misleading.

The Unintended Consequences of Funding Hype

The source of digital litter extends far beyond tech startups. Part of the blame lies at the hands of policymakers, NGOs, and civil-society organizations that seized on the tech hype to create maps or digital platforms aimed at migrants and would-be asylum seekers. Default platforms to consolidate information were sometimes based on time-limited funding, leaving no one to perform updates after the project ended. Initiatives forged in the heat of crisis, such as those to support Syrian refugees in 2015 and 2016, were often not updated online when their offline counterparts expired. And policy circles move slowly; research reports often reference old initiatives or create an insular effect where they all refer to one another, regardless of real-world success.

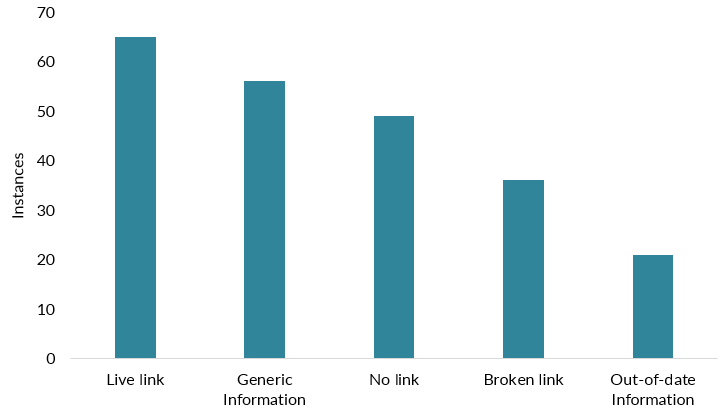

Examples abound. In the world of scholarships and educational opportunities, for instance, the Institute for International Education’s Syria Consortium lists information from 17 U.S. and international universities and other institutions, only one of which links to live, relevant information about scholarships for Syrians. The website of a U.S. nonprofit, Jusoor, posts information about eight university or high school scholarships for Syrian students, most of which do not have up-to-date information or no longer have openings. MOOCs4Inclusion, a website funded by the European Commission that maps digital training offers for migrants and refugees, contains numerous broken links and a not especially prominent disclaimer that the catalogue will only be updated annually as of January 2019. And less than one-third of the 227 opportunities listed on the Refugees Welcome Map hosted by the European University Association contain live links (see Figure 1). The European Resettlement Network fares better in a current-day review of the scholarships it promotes on its site: Of the ten posted at this writing, half linked to broadly up-to-date information. For the other five scholarships, three went to broken links and two pointed to generic information.

Figure 1. Information on Higher Education Initiatives in Refugees Welcome Map, June 2019

Source: Author analysis of Refugees Welcome Map content (manual analysis). European University Association, "Refugees Welcome Map," accessed June 14, 2019, available online.

There are, however, some good actors amid this chaos. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees’ Education and Expert Platform (REEPx), a global scholarship-finder platform, was cancelled after it became clear a similar concept was being developed by an NGO. And the University Alliance for Refugees and At-Risk Migrants, one of whose objectives is to map university efforts to open up higher education to refugees, explicitly decided not to create a digital map or platform because it would duplicate existing efforts.

Such efforts to coordinate and improve the quality of information are critical to expanding complementary pathways, including higher education, recognized by the Global Compact on Refugees as a key tool in addressing record humanitarian displacement.

A Way Forward?

If countries, civil society, and educational institutions are serious about expanding protection to those in greatest need rather than those who already have considerable resources or pre-existing social networks in destination countries, they should consider how to better tailor information to people who may have limited institutional knowledge and understanding of how to navigate unfamiliar systems.

Improving access is not just about consolidating information. In an ideal world, universities that are extending scholarships or other opportunities to refugees would also offer clear multiformat instructions for navigating the immigration system, tailored support for those with untraditional qualifications, and webchat functions. Governments would stop structuring information by department or ministry and instead organize their content by service, accessed through a single portal, and rewrite their immigration forms in plain language. All content would be available in multiple languages, or at least written very simply (the UK government has recently adopted a reading age of 9 for its official web presences since it concluded this was the lowest reading age where still possible to convey complex information).

A Marie Kondo for Digital Litter?

In the meantime, governments, social enterprises, foundations, and others focused on the provision of information or services to refugees and migrants would do well to clean up their digital litter. A few rules of the road can be identified to prevent the problem from developing or escalating further the next time there is a crisis or other moment that brings new actors rushing into the space:

- Give up on the idea of “one platform to rule them all.” Efforts to map and consolidate information into one market-leading platform are sensible in theory, but often fail to deliver on their objective. These can become vanity projects, where competition rules as everyone seeks to have the default platform. Instead, networks could work collaboratively to compare and consolidate information in one place and identify and resolve gaps and inconsistencies.

- Have an exit plan. For the European Commission and other funders of the civic tech initiatives that sprang up in the heat of the 2015-16 crisis to help refugees, this means imposing responsibilities on funding recipients to keep their digital administration in order—carefully dating all content, archiving outdated information, and regularly considering whether anything online could be misleading to someone with more limited knowledge of a particular educational or immigration system.

- Attend to the responsibilities of failure. It has long been noted that the risks of “failing fast” hold much greater consequences in the refugee tech world than in Silicon Valley, but there is much that startups and social enterprises could do to mitigate the costs of such failure. One easy commitment would be for all of those who set up a service to support vulnerable groups to clear out their online presence if their initiative fails or when it otherwise comes to its end.

- Recruit some “Marie Kondos” to clean up the digital litter. Amid the European migration and refugee crisis, there was a bright spot: The revelation that hundreds of young, techie people were willing and eager to work for free on projects aimed at assisting refugees. Platforms for organizing these efforts, such as Techfugees or the European Commission, could now encourage volunteers to deploy their efforts to cleaning up the old, instead of creating the new.

The aftereffects of the European migration crisis are many. The scourge of digital litter pales in comparison to the considerable task of processing and integrating the large numbers of asylum seekers who arrived in Europe in 2015-16. But the digital hangover that emerged from the sense of crisis—especially the lingering effects of dormant initiatives whose founders have now moved onto other things—has been largely ignored. Cleaning up this digital litter could be an easy fix, but it is unclear whose job it is, and requires the time and resources of actors driven by outcome, not ego.

There are also lessons for future migration crises, not least about the importance of tying new initiatives to existing policies and processes to ensure sustainability. While new solutions can be forged in the heat of crisis, governments need a strategy for returning to business as usual that considers how to archive, mainstream, or learn from such innovation.

The author thanks Trevor Shealy for research support.

Sources

Benton, Meghan and Alex Glennie. 2016. Digital Humanitarianism: How Tech Entrepreneurs Are Supporting Refugee Inclusion. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Betterplace lab. N.d. Digital Refugee Projects. Accessed June 14, 2019. Available online.

European Resettlement Network. N.d. Supporting Refugees to Access Higher Education. Accessed June 14, 2019. Available online.

European University Association. N.d. Refugees Welcome Map. Accessed June 14, 2019. Available online.

Gillespie, Marie, Lawrence Ampofo, Margaret Cheesman, Becky Faith, Evgenia Iliadou, Ali Issa, Souad Osseiran, and Dimitris Skleparis. 2016. Mapping Refugee Media Journeys: Smartphones and Social Media Networks. The Open University, 2016. Available online.

Institute for International Education. N.d. Syria Scholarships: Resources. Accessed June 14, 2019. Available online.

Kille, Leighton Walter. 2015. The Growing Problem of Internet “Link Rot” and Best Practices for Media and Online Publishers. Journalist’s Resource blog, October 9, 2015. Available online.

Jusoor. N.d. Jusoor Scholarship Program. Accessed June 14, 2019. Available online.

Mason, Ben. 2016. The Refugee Tech Crisis. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Available online.

---. 2018. The Failings of Refugee Tech. Betterplace lab blog post, July 5, 2018. Available online.

Mason, Ben, Lavinia Schwedersky, and Akram Alfawakheeri. 2017. Digital Routes to Integration: How Civic Tech Innovations Are Supporting Refugees in Germany. Berlin: betterplace lab. Available online.

MOOCs4inclusion. N.d. Mapping & Analysis of MOOCs & Free Digital Learning for Inclusion of Migrants & Refugees. Accessed June 14, 2019. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019. Complementary Pathways for Admission of Refugees to Third Countries: Key Considerations. Geneva: UNHCR. Available online.

University Alliance for Refugees & At-Risk Migrants (UARRM). N.d. Universities as Global Advocates: Empowering Educators to Help Refugees and Migrants. UARRM. Available online.

WPP Government & Public Sector Practice. 2017. Communication for refugee integration. London: WPP. Available online.