You are here

Egypt: Migration and Diaspora Politics in an Emerging Transit Country

Young Egyptians wave flags at a protest in Los Angeles. (Photo: Asim Bharwani)

Egypt is a major migration player in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and in the Global South more broadly, experiencing large, diverse patterns of emigration and immigration, including significant numbers of humanitarian arrivals. As the Arab world’s most populous country, with a population estimated at 97 million, Egypt is also the largest regional provider of migrant labor to the Middle East. More than 6 million Egyptian emigrants lived in the MENA region as of 2016, primarily in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates. Another 3 million Egyptian citizens and their descendants reside in Europe, North America, and Australia, where they have formed vibrant diaspora communities.

Egypt has a long-standing tradition of using emigration as a soft-power tool to advance its foreign policy goals, primarily through educational initiatives across the Arab world. In the last 50 years, it has also become heavily reliant on economically driven regional labor emigration while also reaching out to its diaspora communities in the West. At the same time, Egypt has become a destination for thousands of Arab and African immigrants and a major host of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, Sudanese, and—since 2011—Syrian refugees. Over the past few years, Egypt has also served as a transit country in migrant routes used by sub-Saharan Africans crossing the Mediterranean toward Europe.

This article examines these varied mobility flows, from the 1952 Free Officers Revolution that ended British rule to the aftermath of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution that ousted the Hosni Mubarak regime, including recent efforts by European countries to work with Egypt on stemming migration. It aims to assess and explain the complexities of Egyptian migration policy within a historical and shifting geopolitical context, focusing on the development of policy responses to tackle several issues related to labor emigration, internal movements, immigration, and arrival of the forcibly displaced, as well as relations with Egyptian diaspora communities abroad.

Labor Emigration, Soft Power, and Remittances in the Arab World

Historically, Egypt has been a country of emigration, most of which has occurred within the broader Arab region. Its labor emigration history can be divided into two phases: first, high-skilled emigration across the Arab world throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, and second, primarily low- and medium-skilled outflows to Libya, Iraq, and the oil-producing Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries starting in the early 1970s.

Having achieved nominal independence from the Ottoman Empire much earlier than the rest of the MENA region, Egypt became a trendsetter and a major force within the Arab world. Large-scale modernization efforts throughout the 19th century, which continued under British rule from 1882 to 1952, led to a vibrant, educated elite class. Many Egyptian professionals would travel to North Africa, the Levant, and the Persian Gulf to contribute to the economic development of neighboring areas. As Arab nationalism came to dominate Cairo in the aftermath of World War I, Egyptian high-skilled emigration became a political project focused primarily on education and Arab empowerment. Under British rule, the Egyptian government welcomed the enrollment of non-Egyptian Arab students at Al-Azhar University and the newly established Cairo University, funded the construction of schools across the region, and staffed them with qualified Egyptian teachers and administrators.

This trend continued after the 1952 Free Officers movement, which abolished the British-supported Egyptian monarchy and brought to power a new generation of anticolonial revolutionary elites led by Gamal Abdel Nasser. Under President Nasser, Egypt heavily restricted labor emigration but continued to sponsor the employment of high-skilled professionals across the MENA region. In contrast to earlier efforts, such mobility constituted less a sign of Arab solidarity and more a tool of foreign policy. In the 1950s and 1960s, the government recruited, trained, and dispatched thousands of Egyptian professionals—particularly teachers—across Africa, to Latin America and, most importantly, throughout the Arab world. Once abroad, many Egyptians disseminated the Free Officers’ rhetoric on anticolonialism and anti-Zionism, and promoted nationalist sentiments—effectively serving as one of Egypt’s most potent instruments of soft power. As a result, Egyptian high-skilled emigration throughout the 1950s and 1960s played a key role in several political processes across the Global South, including the decolonization of Africa and the Middle East, the North Yemen Civil War, and the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Despite the popularity of international placements for state-sponsored professionals, the Free Officers resisted any attempt to allow broader free movement of labor into and out of its territory, as they were eager to prevent brain drain of talent or the flight of political opponents abroad. During most of Nasser’s rule, emigration was restricted and tightly regulated (although many still found ways to escape Egypt, most notably members of the Muslim Brotherhood), a policy that became untenable by the end of the 1960s. The deteriorating domestic economic situation, particularly following Egypt’s devastating defeat in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, led Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, to implement a massive liberalization of the economy in a process known as al-Infitah. As part of this shift, President Sadat recognized emigration as a citizen’s right, lifting all restrictions on Egyptians’ crossborder mobility in 1971—thereby inaugurating the second phase of Egyptian labor emigration.

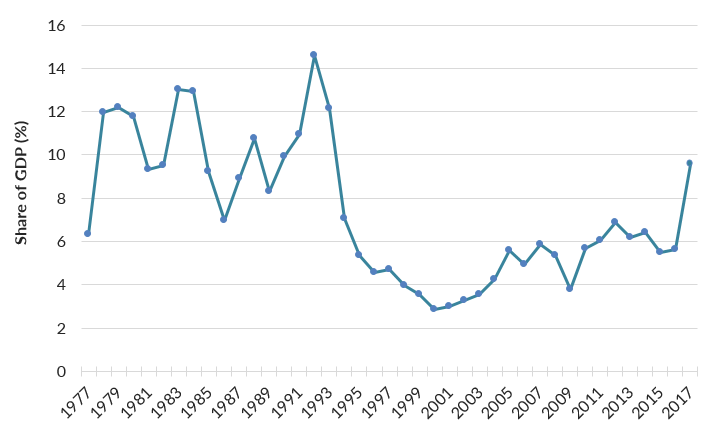

This era was dominated by large outflows into oil-producing Arab states, particularly following the 1973 oil crisis. Following the emigration policy shift, millions of high- and low-skilled Egyptian workers pursued employment across the Middle East, partly driven by domestic unemployment and the vast wage gaps between Egypt and key host countries. Since then, Egypt has considered economic remittances to be a key source of income, which now constitute a significant share of its gross domestic product (GDP) (see Figure 1). Given that money transfers are also conducted via unofficial, untraceable channels, the economic importance of migration for Egypt is even higher. Beyond remittances, labor migration has served as an important safety valve for the Egyptian government, which has traditionally struggled with issues of unemployment and overpopulation.

Figure 1. Annual Remittances Received in Egypt, as Share of GDP (%), 1977–2017

Source: World Bank, “Personal Remittances, Received (% of GDP),” accessed August 7, 2018, available online.

In terms of destination countries, neighboring Libya was the primary destination for Egyptian migrants until the mid-1970s. Once there, approximately one-third of Egyptians were employed jointly in the public administration, education, and health sectors; one-quarter worked in agriculture. From the mid-1970s onward, most Egyptian migrant workers headed to the Gulf region, notably Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Iraq. Migrant recruitment in the GCC states operates under the Kafala system, requiring hired migrants to have an in-country sponsor, who holds considerable power and control over workers. This system of migrant labor recruitment has been widely criticized by international organizations and others for enabling human-rights violations against migrant workers across the Gulf.

The post-1979 decline in oil prices has contributed to a steady fall in Egyptian recruitment in the oil-producing Arab countries. At the same time, Egyptian regional emigration to the Gulf has slowed since the 1980s due to a shift toward the recruitment of Asian migrant labor. In contrast to Arab migrants, Asian workers are considered to be cheaper and less likely to be involved in the domestic politics of destination countries.

The decision of some GCC countries to get more of their nationals into the labor force, from the early 1990s onwards, has also affected Egyptian migration flows. At the same time, the prohibition of permanent migration across the Gulf has made circular movement common, although Egyptians tend to stay in these countries for many years. This phenomenon has also increased the appeal of traditional transit migration countries—such as Jordan—which now host large populations of Egyptian migrants (see Table 1).

Table 1. Egyptian Migrants in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), 2016

Source: Arab Republic of Egypt Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), “Egyptians Abroad” (fact sheet, CAPMAS, 2017), available online (in Arabic).

Beyond economic changes, war and high politics have also affected Egyptian labor migration. For example, Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait led to the exodus of the entire Egyptian community in 1990. Libya effectively ceased to be a major country of destination following the 2011 overthrow of the Muammar Gaddafi regime and the country’s ensuing descent into civil war. At the same time, Egyptian migrant flows have depended on governments’ use of diplomatic tools and processes to manage crossborder mobility—what Fiona Adamson and the author call “migration diplomacy.”

Several examples illustrate this phenomenon. Egyptians in Libya suffered abuse and deportation under Gaddafi whenever bilateral relations with Cairo deteriorated. In 1990, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein ordered the exodus of more than 1 million Egyptians in retaliation for President Mubarak’s support of Operation Desert Storm; many were quickly absorbed by Saudi Arabia, one of Egypt’s strongest regional allies. More recently, the deterioration of Jordanian–Egyptian relations in 2012–13 led to the abuse and deportation of hundreds of Egyptian migrant workers, who were only invited to return once interstate relations improved.

Urbanization and Internal Migration

Beyond aiming to tackle unemployment and attract remittances, Egypt’s liberalization of emigration was also driven by rising urbanization. From 1952 onward, the Free Officers’ policies of nationalization and state-led industrialization contributed to significant internal migration, as Egyptians abandoned rural areas and moved to cities such as Alexandria and Cairo. The 1967 Arab–Israeli War exacerbated this trend, as the Israeli occupation of the Sinai Peninsula led to the internal displacement of more than 1 million Egyptians, who fled to Cairo.

Egyptian policymakers feared the potential implications of the twin phenomena of overpopulation and urbanization, and thus actively pursued labor emigration as a solution from the 1970s onwards. Yet urbanization continued, with negative effects on housing, public health, and transportation. Cairo alone, which at the turn of the 20th century had 590,000 residents, now struggles to meet the needs of some 20 million people in the greater metropolitan area. It is the most populous city in Africa and in the Middle East and the fourth-largest in the world, according to United Nations data.

Migration to the West and Egyptian Diaspora Policy

Beyond seeking employment across the MENA region, millions of Egyptians have also emigrated to Western countries, particularly once the Nasser-era obstacles to emigration were lifted. Emigration to the West initially consisted of small groups of Egyptian students on state-sponsored scholarships or political dissidents seeking to escape persecution. Gradually, as mobility restrictions were relaxed, hundreds of thousands relocated to the West. The resurgence of political Islam in Egypt and the broader Middle East from the early 1970s onwards contributed to the emigration of large numbers of Egyptian Copts to the West, who began leaving in the 1970s. Copts have created vocal diaspora communities, particularly in North America, that have sought to defend the interests of Christians in Egypt.

Over the past few decades, in the face of stricter immigration controls across the European Union, greater numbers of Egyptians have crossed into Europe via the Mediterranean, creating a large community of low-skilled Egyptian migrants in Southern Europe.

In 1971, Egypt began classifying emigrants by their country of destination, definitions later enshrined in a 1983 law. Egyptians living in Arab countries are invariably considered “temporary workers,” even when they have lived there for decades, while all those in Australia, Europe, North America, or elsewhere are deemed “permanent migrants,” regardless of time spent in their host countries. This has contributed to a multi-tier emigration policy that favors Egyptians in the West at the expense of those residing in Arab countries. Gradually, Egypt developed a diaspora policy to accommodate the needs and wishes of these “permanent emigrants.”

From the 1970s on, Egypt has put forth several initiatives to engage with and leverage its diaspora. Egyptian policymakers view permanent migrants as well-off, educated, and successful, and have developed instruments within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other agencies to harness their potential, promote return migration, and reverse the phenomenon of brain drain. This includes providing government-paid trips to Egypt, as well as targeted outreach to diaspora members via embassies and consulates. In the aftermath of the 2011 revolution, Egypt granted expatriates the right to vote from abroad in parliamentary elections.

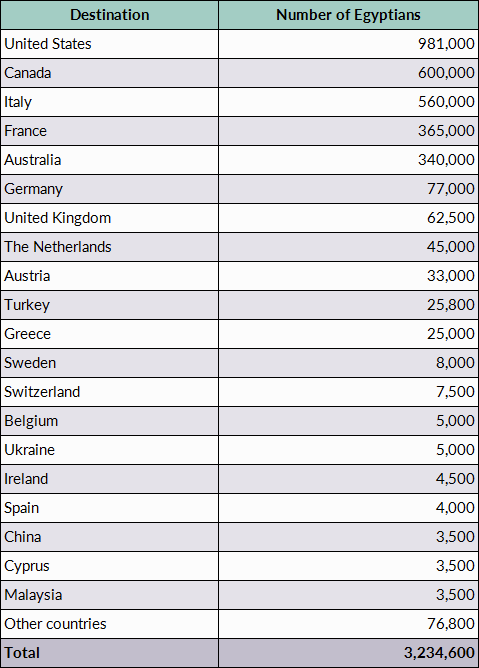

Table 2. Egyptian Citizens and Descendants Living Outside the MENA Region, 2016

Source: CAPMAS, “Egyptians Abroad,” available online (in Arabic).

However, the government’s relationship with the diaspora has been fraught, as Egyptian communities abroad have not hesitated to organize protests against government policies, particularly during the Sadat years. The diaspora’s divisions along many lines (social class, political, ideological, religious) and the wish of migrants to be able to return to Egypt without fear of arrest or reprisal generally prevented mass mobilization attempts during the Mubarak era.

A major shift occurred once Nobel laureate and former Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency Mohamed ElBaradei sought to enter Egyptian politics as an opposition leader in the months before the 2011 Egyptian Revolution. Diaspora groups rallied in support of ElBaradei and the long-standing issue of out-of-country voting. Quickly, diaspora organizations multiplied and held vocal protests across the West, seeking to contribute to Egypt’s short experiment with democratization; the Muslim Brotherhood was elected into power in 2012.

The Egyptian military’s takeover in 2013 led to the exodus of Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood members, who sought to avoid persecution by fleeing to Turkey and Qatar, in particular. The ousting of the Muslim Brotherhood from office also produced a deep political polarization in the country that has been mirrored abroad, as Egyptian diaspora communities continue to be divided on the legitimacy of the military intervention. At the same time, reports of government harassment and arrests of Egyptians abroad are increasing.

Shifting Attitudes toward Immigrants and Refugees

A sharp contrast exists between the regulation and institutionalization of Egypt’s emigration policies and that of its refugee and immigration policies. Although Egypt is a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, its 1967 Protocol, and the 1969 Organization for Arab Unity Refugee Convention, the country’s implementation of related obligations has been ad hoc. Formal policies regarding migrants and refugees are frequently absent or, even when regulations exist, the government may turn a blind eye to informal practices that contravene them. All too frequently, the fate of refugee communities is subject to shifting political exigencies.

While pre-1952 Egypt was a welcoming home to foreigners—including thriving communities of Greek Egyptians, Italian Egyptians, and Syrians—the wave of nationalism that accompanied the Free Officers Revolution contributed to the decline of cosmopolitan Egypt. The regime-sponsored nationalization of foreign enterprises and the emphasis on import-substitution industrialization policies, within a broader anti-Western, postcolonial political climate, also played a role, as immigration into Egypt fell throughout the Nasser period.

The sole exception was an influx of Palestinian refugees, who fled violence following the 1948, 1956, and 1967 Arab-Israeli Wars. Although they were not granted protection by formal UN institutions, Palestinians in Egypt enjoyed the support of the Nasser regime. This was due to Nasser’s anti-Zionist rhetoric and the ongoing military operations against Israel, coupled with the regime’s rhetoric promoting Arab solidarity and its desire for Arab leadership.

By the mid-1970s, the situation had shifted considerably. Sadat abandoned Nasser’s anti-Zionism for bilateral rapprochement with Israel, and Egypt signed the 1977 Camp David Accords with Israel, negotiated without input from Palestinians. During this period, Palestinians in Egypt lost a number of rights, including legal residency, employment, and property ownership. This became a problem for Palestinians without Egyptian citizenship (primarily acquired via marriage to Egyptian nationals), who retained their refugee status. Today, roughly 300,000 Palestinians live in Egypt.

Egypt’s relations with Israel have affected both the government’s policy toward Palestinians as well as its approach to sub-Saharan African refugees seeking to reach Israel. In terms of the former, Egyptian–Israeli cooperation has sustained the ongoing blockade of the Gaza Strip since 2007, once Hamas (an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood) assumed power. Egypt’s strict border controls at the border city of Rafah have prevented Palestinians from reaching Gaza for weeks or months on end. Tacit intelligence and military cooperation with Israel has also aimed at preventing Africans crossing Egypt—notably Sudanese, Ethiopians, and Eritreans—from reaching Israel to seek asylum.

In fact, the fate of the Sudanese community in Egypt has historically been tied to politics. Until 1995, Sudanese nationals enjoyed visa-free entry into Egypt and unrestricted access to social provisions, including employment, education, health coverage, and property ownership. These rights were secured by the 1976 Wadi El Nil bilateral agreement, which aimed to strengthen cooperation between the two countries. Yet, the 1995 assassination attempt on Mubarak—allegedly by Sudanese Islamists—led to the agreement’s repeal, and with it a gradual rise in human-rights abuses against Sudanese in Egypt. Since 1995, just a fraction of Sudanese arriving into Egypt have been able to register as refugees with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). As a result, measuring the size of the Sudanese community in Egypt has been very difficult: estimates range from 750,000 to 4 million.

Finally, Egypt is also home to a sizeable Syrian refugee community. In the immediate aftermath of the 2011 Arab Spring events and start of the Syrian civil war, the Muslim Brotherhood government welcomed Syrians, who were exempt from entry visas and allowed to enter on three-month tourist visas and register with UNHCR. Once the military resumed power in mid-2013, Egypt toughened its stance, requiring Syrians to obtain a visa prior to arrival and register with the government once their visa expired. As of April 2018, nearly 130,000 registered Syrians lived in Egypt, though the government estimates that the total number is 300,000.

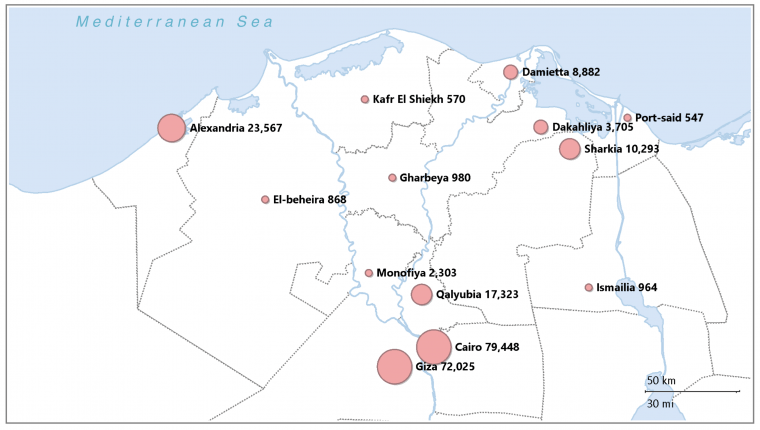

Figure 2. Syrian Refugee Communities in Egypt, April 2018

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “UNHCR Egypt Monthly Statistical Report” (fact sheet, UNHCR, April 30, 2018), available online.

Egypt’s Legal Migration Framework: Non-Policy as Policy?

Over the years, Egypt has developed a number of legal regulations and established ministries and other institutions to govern international migration. The liberal emigration policy included in the 1971 Constitution formed the basis of Law No. 111 of 1983, on Emigration and Egyptians’ Welfare Abroad. This law also allows for dual citizenship, and defines temporary workers abroad and permanent migrants, as discussed above. The Constitution guarantees the right to emigrate, and Law No. 111 recognizes the rights of permanent migrants, such as their exemption from paying taxes in Egypt.

Egypt has signed several bilateral agreements related to emigration, primarily with Arab countries, since 1970. On immigration and refugee matters, Law 88 of 2005 regulates the entry, stay, and exit of foreign nationals. Egypt has also ratified several International Labor Organization treaties, the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, as well as the 2000 Palermo protocols on human trafficking. Today, Egypt is a member state of the African Union, the League of Arab States, and the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (or CENSAD), all of which involve some level of cooperation on migration issues.

Two notable facets characterize the legal and institutional framework governing migration management in Egypt. First, Egypt follows a pattern seen in other MENA countries, having developed unclear immigration and refugee policies. Its “strategic ambivalence” toward these issues, to borrow Kelsey Norman’s term, allows the proliferation of informal practices that override formal regulations: For instance, refugees can gain employment across Egypt’s large informal sectors, yet these practices are not sanctioned or protected by government regulations, thereby further exacerbating these communities’ precarious position.

A second and related point refers to decision-making processes: Despite the plethora of structures set up to manage migration, policymaking frequently takes place in the highest echelons of the executive branch, rather than within transparent bureaucratic mechanisms, the legislature, or other institutionalized processes. Jordan’s deportation of hundreds of Egyptian workers in 2012, for instance, ceased following a phone call by the Egyptian President to the Jordanian monarch. The content of numerous bilateral labor migration treaties (primarily with GCC countries) is never made public.

Future Migration Prospects in a Post-Arab Spring Egypt

What might Egypt’s past migration management practices indicate about its future in terms of crossborder mobility? Two issues bear attention: the political economy of the Arab world and Egypt’s strategic importance in regional migration interdependence. In terms of the former, the collapse of the Gaddafi regime in Libya and the country’s post-2011 instability have generated an influx of return migration to Egypt, while diminishing Libya’s capacity to serve as a host for Egyptian labor. The continual shift of GCC countries away from recruiting Egyptian labor has also worsened employment prospects for young Egyptians in the Gulf.

These developments have compounded ongoing economic problems in Egypt, already aggravated by the collapse of tourism and deteriorating public finances. This has contributed to the recent increase of irregular migration across the Mediterranean, while it may also lead to the crowding out of refugees and immigrants from informal jobs by would-be emigrants who had to stay put. If labor emigration can no longer serve as a safety valve, as it has done since the early 1970s, then a new wave of protests is likely, despite President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi sustained crackdown on political dissenters.

From an international political perspective, these developments constitute both a threat and an opportunity for Egypt. As its reliance on remittances grows and the pool of destination-country opportunities shrinks, Egypt is now increasingly vulnerable to the demands of these countries—and smaller ones such as Jordan have begun using Egyptian migrants as bargaining chips.

At the same time, regional instability and a rise in irregular migration across the Mediterranean to Europe have raised the strategic value of Egypt in the eyes of the European Union. Since 2015, security and migration management have been key issues in the European Neighborhood Policy toward Egypt and other MENA countries. European leaders, fresh from the March 2016 EU-Turkey agreement that stemmed irregular migration flows into Southern Europe, have been keen to export this model to North Africa. In August 2017, Germany negotiated an agreement with Egypt aiming to prevent people from leaving Egyptian shores—a departure point for a growing number of migrants and refugees since being driven out of Turkey. Not unlike other countries south of the Mediterranean, Egypt sees this as an opportunity for increased foreign aid and employment opportunities.

Overall, the examination of Egyptian migration policy points to the sheer complexity that exists in the management of diverse forms of mobility across the Global South. Foreign policy pressures interact with domestic economic needs within a shifting geopolitical context, where legacies of the past continue playing an important role. A common thread that runs across Egypt’s policies (or, in certain aspects, non-policies) is the instrumentalization of migration—be it for purposes of soft power, bilateral cooperation, or economic or domestic political gain. The extent to which such approaches contribute to the resolution—or perpetuation—of “migration crises” is open to debate.

Sources

Adamson, Fiona and Gerasimos Tsourapas. Forthcoming. Migration Diplomacy: Investigating the International Politics of Mobility Management. International Studies Perspectives.

Arab Republic of Egypt Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). 2017. Egyptians Abroad. Fact sheet, CAPMAS. Available online (in Arabic).

Birks, J. S. and C. A. Sinclair. 1980. International Migration and Development in the Arab Region. Geneva: International Labor Office.

Brand, Laurie A. 2014. Arab Uprisings and the Changing Frontiers of Transnational Citizenship: Voting from Abroad in Political Transitions. Political Geography 41 (July): 54–63.

Brinkerhoff, Jennifer M. 2005. Digital Diasporas and Governance in Semi‐Authoritarian States: The Case of the Egyptian Copts. Public Administration and Development 25 (3): 193–204.

Dalachanis, Angelos. 2017. The Greek Exodus from Egypt: Diaspora Politics and Emigration, 1937-1962. New York: Berghahn Books.

Dessouki, Ali E. Hillal. 1982. The Shift in Egypt’s Migration Policy: 1952-1978. Middle Eastern Studies 18 (1): 53–68.

Di Bartolomeo, Anna, Tamirace Fakhoury, and Delphine Perrin. 2010. Egypt, The Demographic-Legal-Socio-Political Economic Framework of Migration. Florence: European University Institute.

Dorman, W. Judson. 2007. The Politics of Neglect: The Egyptian State in Cairo, 1974-98. Doctoral thesis, University of London School of Oriental and African Studies. Available online.

Ghoneim, Ahmed Farouk. 2009. Evaluating the Institutional Framework Governing Migration in Egypt. Cairo: Partners in Development. Available online.

Hollifield, James F. 2004. The Emerging Migration State. International Migration Review 38 (3): 885–912.

Howaida, Roman. 2006. Transit Migration in Egypt. Florence: European University Institute. Available online.

Kapiszewski, Andrzej. 2006. Arab versus Asian Migrant Workers in the GCC Countries. Beirut: UN Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online.

Kerr, Malcolm H. and El Sayed Yassin. 1982. Rich and Poor States in the Middle East: Egypt and the New Arab Order. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Norman, Kelsey P. 2016. Migrants, Refugees and the Egyptian Security State. International Journal of Migration and Border Studies 2 (4): 345–64.

---. 2017. Ambivalence as Policy: Consequences for Refugees in Egypt. Égypte/Monde Arabe 1 (15): 27–45.

Paoletti, Emanuela. 2011. Migration and Foreign Policy: The Case of Libya. The Journal of North African Studies 16 (2): 215–31.

Philipp, Thomas. 1985. The Syrians in Egypt: 1725-1975, Vol. 3. Philadelphia: Coronet Books Inc.

Talani, Leila Simona. 2010. From Egypt to Europe: Globalisation and Migration Across the Mediterranean. London: Tauris Academic Studies.

Tsourapas, Gerasimos. 2014. Notes from the Field: Researching Emigration in Post-2011 Egypt. American Political Science Association Migration & Citizenship Newsletter 2 (2): 58–63.

---. 2015. Why Do States Develop Multi-Tier Emigrant Policies? Evidence from Egypt. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (13): 2192–214.

---. 2016. Nasser’s Educators and Agitators across Al-Watan Al-‘Arabi: Tracing the Foreign Policy Importance of Egyptian Regional Migration, 1952-1967. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 43 (3): 324–41.

---. 2017. Migration Diplomacy in the Global South: Cooperation, Coercion and Issue Linkage in Gaddafi’s Libya. Third World Quarterly 38 (10): 2367–85.

---. 2018. Authoritarian Emigration States: Soft Power and Cross-Border Mobility in the Middle East. International Political Science Review 39 (3): 400-16.

---. 2018. Labor Migrants as Political Leverage: Migration Interdependence and Coercion in the Mediterranean. International Studies Quarterly.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2018. UNHCR Egypt Monthly Statistical Report. Fact sheet, UNHCR, April 2018. Available online.

Waterbury, John. 1973. Cairo: Third World Metropolis. New York: American Universities Field Staff.

---. 1983. The Egypt of Nasser and Sadat: The Political Economy of Two Regimes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

World Bank. N.d. Personal Remittances, Received (% of GDP). Accessed August 7, 2018. Available online.

Zohry, Ayman and Barbara Harrell-Bond. 2003. Contemporary Egyptian Migration: An Overview of Voluntary and Forced Migration. Brighton, UK: University of Sussex Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation, and Poverty.