You are here

Once Primarily an Origin for Refugees, Ethiopia Experiences Evolving Migration Patterns

A woman and her child in southern Ethiopia. (Photo: Nena Terrell/USAID Ethiopia)

Ethiopia’s strategic location in the Horn of Africa, its long history, and large ethnic and linguistic diversity make it a melting pot of dynamic cultures and customs. The country is known for its historical resistance to colonialism, including to Western powers in the 19th century, and was only briefly occupied by Italian forces before World War II.

Partly for this reason, migration outside the region has been a recent relatively phenomenon, with emigration growing in the 20th century amid domestic repression, humanitarian crises, and attractive labor opportunities abroad. In the 1970s and 1980s large numbers of Ethiopians became refugees as their country was overtaken by war, famine, and natural disaster. Many of these refugees returned, and subsequent migration has been more complex in terms of the drivers, individuals who migrate, and countries of destination. Many Ethiopian emigrants have sought economic opportunities in the Middle East, North America, Europe, and elsewhere in Africa, and this diaspora has had a growing effect on the country’s politics and development. Large numbers of migrants particularly from elsewhere in the Horn of Africa also pass through Ethiopia on their way towards Europe or other common destinations.

In addition to being an important country of origin, Ethiopia is also a prominent destination for a range of migrants, particularly those fleeing conflict from elsewhere in East Africa and the Horn. Ethiopia has an advanced regime for the protection of forced migrants and hosts approximately 789,000 refugees, most of them residing in 24 camps across the country. Recently, Ethiopia has also confronted significant involuntary repatriation of its emigrants, mainly from prominent destinations in the Middle East; this situation has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This article aims to shed light on the past and current migration landscape in Ethiopia by discussing the complex movement of people from, through, and to the country. It reviews key migration management policies as well as the challenges and opportunities posed by recent migration flows.

History of Migration in Ethiopia

Researchers have observed that colonial ties play an important role in shaping patterns of migration out of Africa, with the vast majority of emigrants tending to settle in countries with colonial and linguistic ties. Having never been colonized, Ethiopia does not share these ties with either African or European countries, and so migration patterns do not follow a well-defined route. While the Middle East has become a prominent destination for labor migrants, Ethiopia’s diaspora is scattered over a range of continents. A large portion of those settling in the country are from neighbors in the Horn of Africa.

Socioeconomic, environmental, and political crises in Ethiopia over the last 50 years have led to a major migration of people, both internally and across borders. The country has suffered extreme political turmoil, recurrent drought, famine, and devastating civil war. Ethiopia has witnessed major droughts and famines since the mid-1960s, which were often met by compulsory internal resettlement and so-called “villagization” land reform programs that relocated rural communities into villages. Significant international movement also occurred: during the mid-1980s famine, which took place in the midst of civil war, approximately 600,000 Ethiopians fled to neighboring Sudan.

Notably, large-scale international emigration from Ethiopia has tended to occur during periods of political repression and changes of government. There have been at least three distinct waves: before the 1974 revolution, when small numbers of elites migrated to Western countries to obtain training and higher education; under the military government and during the Qey Shibir (“Red Terror”) from 1974 to 1991; and in the post-Derg period, during which large numbers of refugees returned to Ethiopia and yet intermittent ethnic violence, political repression, and the lure of economic opportunity prompted more departures. These successive waves contributed to the emergence and development of the Ethiopian diaspora mostly in North America, Europe, and the Middle East.

Pre-Revolutionary Ethiopia: Before 1974

Ethiopia had been ruled by successive emperors until Haile Selassie was overthrown by a Marxist military junta called the Derg in 1974. While emigration was generally insignificant during Selassie’s tenure, which began in 1930, the movement that existed was characterized by the urban elite’s departure to Western countries to seek training and education. Notably, there is evidence suggesting the emperor was keen to modernize Ethiopia through expanding education. Selassie was a popular leader in Africa and enjoyed support from Western allies. Between 1941 and 1974, an estimated 20,000 Ethiopians departed overseas as students and diplomats.

Interestingly, the rate of return of Western-educated migrants during this period was reportedly high, often because these returnees came back to fill important government positions. Comparatively, the number of refugees and asylum seekers was negligible, as the country was generally stable despite the emperor’s political repression and limited freedom.

Post-Revolutionary Ethiopia: The Derg Era

The Derg seized power in 1974 and declared the country a socialist state. Two months later, the government executed dozens of political opponents, marking the start of a new emigration wave. The Derg’s time in power was characterized by war with internal rebel groups that evolved around the time the regime seized control, many of them seeking liberation of regional states such as Eritrea. The government’s Qey Shibir campaign was launched in response, and the civil war lasted until the Derg’s collapse in 1991. During the conflict, which overlapped with the mid-1980s famine, well more than 1 million people were estimated to have died. In 1977 and 1978 Ethiopia was also engaged in a border dispute with neighboring Somalia known as the Ogaden War. Both conflicts led to large-scale humanitarian displacement, both internally and internationally.

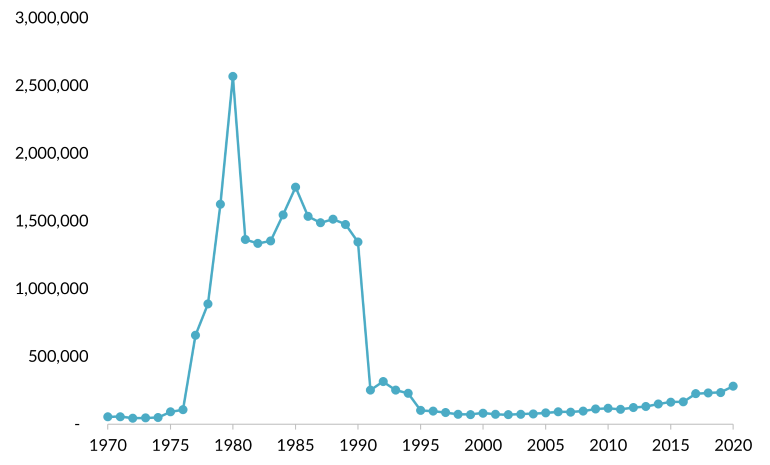

At the peak in 1980, well more than 2.5 million Ethiopians were living as refugees or other forcibly displaced migrants (see Figure 1). Most of these refugees went to neighboring states, mainly Sudan and Kenya, and many were eventually resettled in Western countries, notably the United States, Europe, and Australia. Between 1982 and 1990, Ethiopians accounted for 90 percent of African refugees resettled in the United States.

Figure 1. Forced Migrants from Ethiopia, 1970-2020

Note: Data refer to the number of refugees under the protection of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), asylum seekers, and others of concern to UNHCR as of the end of the year.

Source: UNHCR, “Refugee Data Finder,” accessed September 13, 2021, available online.

In addition to this humanitarian migration, student migration to socialist countries such as Cuba, the former Soviet Union, and East Germany was also common during the Derg regime.

Post-Derg Period: From 1991 to the Present

After the Derg’s collapse in May 1991, the regime was replaced by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) coalition, of which the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) was the dominant faction. The post-1991 period has witnessed fundamental structural changes in political and development policies, along with continued turmoil and conflict with neighboring countries.

The change of government in 1991 allowed for the return of more than 970,000 Ethiopian refugees from neighboring countries. However, there have continued to be major crises leading to new outflows of refugees, including political repression and ethnic violence in the early 1990s and 2000s, the border dispute with Eritrea from 1998 to 2000, and post-election violence in 2005. While the number of people forcibly displaced has been much lower than in previous years, some scholars have argued that the overthrow of the Derg regime did not bring more equality and less repression.

International labor migration has also significantly increased in this period, as citizens have been able to obtain passports and move abroad more easily. It intensified due to poverty in Ethiopia, migrants’ expanded social networks, the growth of recruitment agencies both legal and illegal, the relative fall of migration costs, and high demand for domestic work in destination countries such as Saudi Arabia.

Ethiopia as a Country of Origin and Transit

In recent years, emigration has risen dramatically from Ethiopia, and the country is also a central hub for migrants traveling across the Horn of Africa. This movement is increasingly characterized by its irregularity, as migrating through regular channels is often challenging and beyond the reach of the poor.

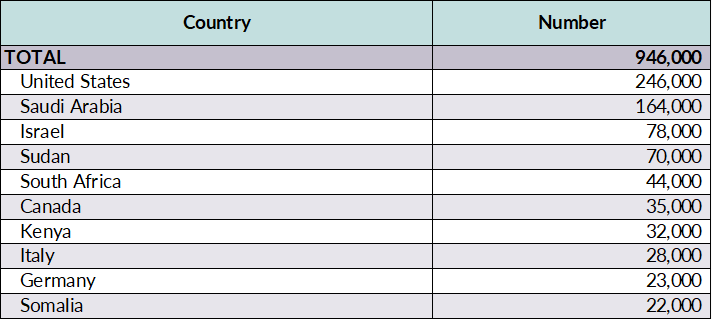

The government has estimated that there are around 3 million people in the Ethiopian diaspora, although UN Population Division estimates put the number of emigrants at fewer than 1 million. In 2020, the top destinations for Ethiopian migrants were the United States, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Sudan, and South Africa (see Table 1). In the absence of colonial linkages, the destinations of Ethiopian emigrants can be explained by a combination of factors including geographic proximity, migrant networks, destination countries’ policies, and other historical links. For instance, since the 1980s tens of thousands of Ethiopian Jews have been brought to Israel directly from Addis Ababa and Sudanese refugee camps with the help of the Israeli government.

Table 1. Ethiopian Emigrants by Country of Residence, 2020

Source: United Nations Population Division, “International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin,” 2020, available online.

In recent decades, economic factors have been the most common drivers of migration from Ethiopia, followed by political reasons including oppression, insecurity, and ethnic tensions. Migration is increasingly perceived as the only way out of poverty in Ethiopia, especially for the rural youth. Saudi Arabia and other countries in the Middle East have been top destinations for Ethiopians looking for economic opportunity. Traffickers, smugglers, and family members also encourage people to emigrate.

The bulk of labor migration from Ethiopia is for low-skilled work, however the departure of skilled migrants to Western countries and other emerging economies in Africa is on the rise. For instance, Ethiopia has in recent years experienced a significant migration of health-care professionals, and there were more Ethiopian doctors working in Chicago in 2012 than in all of Ethiopia, according to the health minister at the time. Nearly one-third of Ethiopians who resided in countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) had more than a high school education as of 2015 and 2016. Highly skilled migrants tend to reside in the United States and Europe.

Although its humanitarian migrant numbers are a fraction of what they were in the 20th century, Ethiopia remains one of the continent’s largest countries of origin for refugees and asylum seekers, with an estimated 280,000 Ethiopians living in this status as of 2020. Numbers have recently risen due to a violent conflict in the northern Tigray region that broke out between the federal government and TPLF leaders in November 2020. More than 60,000 refugees fled the conflict, mainly from Tigray, in what has been the largest refugee outflow from Ethiopia in decades, with most heading to Sudan. The situation has also resulted in huge internal displacement: As of September, approximately 4 million Ethiopians were internally displaced.

At the same time, Ethiopia has developed into a major transit point through and out of the Horn of Africa, particularly for migrants from Eritrea and Somalia. Sitting at the nexus of the Horn and East Africa, Ethiopia is pivotal for migrants from across the region aiming to reach Europe and other northern destinations.

Migrants from and traveling through Ethiopia tend to travel along three major migration corridors: eastward to the Persian Gulf states and the Middle East, crossing the Red Sea or the Gulf of Aden; southward to South Africa; and northward across the Sahara, into Sudan and often to Europe. The route chosen by migrants will depend on their income, social status, migration history, and international connections; those with the least alternatives generally choose the most dangerous journeys.

Figure 2. Common Migration Routes from Ethiopia

Source: MPI artist rendering.

The Eastern Route

Movement from Ethiopia to the Middle East has been ongoing at a high rate since the early 1990s. Migrants traveling this path are increasingly characterized by their irregular status. According to Ethiopia’s Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, approximately 1.5 million Ethiopians traveled to the Middle East via irregular channels between the years 2008 and 2014; more than 480,000 Ethiopians moved to Arab countries legally during these years. In 2017, an estimated 500,000 Ethiopian migrants lived without status in Saudi Arabia alone. However, hundreds of thousands of migrants have been returned from the region, often after being detained for immigration offenses.

Historically, many Ethiopian migrants to the Middle East have been young, single females migrating as domestic workers or sometimes for custodial work in institutions such as clinics and schools. Women account for about 95 percent of all legally present migrants from Ethiopia in the region. The men who make this journey through regular channels have often been employed in construction and farm work, or perhaps as drivers or mechanics.

Ethiopia has over the last decade signed bilateral labor agreements with Jordan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates to increase legal migration, which benefitted legally present Ethiopian migrants but also sped up returns for those who were unauthorized. In response to a rash of forced returns and complaints of abuse abroad, the government in 2013 banned Ethiopians from traveling to the Middle East. Restrictions remained in place for five years, at which point the ban was lifted and the government imposed new regulations on recruitment agencies, among other reforms. While it may have halted legal labor migration to countries without bilateral agreements in place, this ban likely spurred some migrants to move illegally.

Yemen has been an important transit and destination country for Horn of Africa migrants traveling the eastern route, a role that has continued even during the country’s civil war that started in late 2014. Many migrants have remained unaware of the ongoing conflict. From Yemen, many migrants are smuggled into Saudi Arabia. The Gulf of Aden has regularly been among the busiest maritime migration routes on the planet; more than 138,000 people crossed into Yemen in 2019, approximately 92 percent of whom were Ethiopian nationals, and 150,000 in 2018. In 2020, amid the coronavirus pandemic, the number of arrivals in Yemen declined to 37,500.

The Southern Route

The southern route runs from the Horn of Africa towards South Africa. Ethiopia and Somalia are major source countries, with Ethiopians accounting for an estimated two-thirds of travelers. This migration began in the early 1990s, partly in response to the end of apartheid as well as turbulence in Ethiopia and migrants’ growing social networks, and it has increased since. An estimated 95 percent of Ethiopian migrants arrive in South Africa through irregular channels and quickly regularize their status through the asylum system, according to a 2009 analysis.

As many as 14,000 Somalis and Ethiopians were estimated to make the journey to South Africa annually as of 2017, when there were an estimated 120,000 Ethiopian migrants in the country. Youths from southern Ethiopia often take this route, particularly young men from the Hadiya and Kembaata ethnic groups with little or no education. Irregular migration to South Africa requires crossing several countries and entails high risk, including physical and emotional stress, possibility of imprisonment, deportation, or even death. A chain of smugglers facilitates movements often from Hosanna, the capital of southern Ethiopia’s Hadiya Zone, and Nairobi. Corruption especially among law enforcement helps support the transnational smuggling business. However, growing xenophobia in South Africa and throttling efforts by transit states such as Kenya, Tanzania, and Malawi have reduced the numbers of migrants traveling along this route since 2015. Reports of arrest and deportation in transit have been common, particularly since the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020.

The Northern Route

Migrants from Ethiopia tend to use the northern route only in rare cases, but it is more commonly traversed by Eritrean and Somali nationals who travel through Ethiopia. Many migrants from the Horn of Africa tend to transit through Sudan on their way to Libya and Europe, however many do not end up crossing the Mediterranean, contrary to many public narratives. In 2020, Sudan was the fourth largest destination for Ethiopian migrants, and Libya had also been a common destination for migrants until the 2011 overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi.

The northern migration route has received significant media and political attention, partly because of the harsh conditions in Libya, the dangers in crossing the Mediterranean, and restrictive policies in Europe. Consequently, the number of people from the Horn of Africa arriving in Europe decreased from more than 30,000 in 2016 to fewer than 4,000 in 2018.

Ethiopia as a Country of Destination

Ethiopia has a longstanding tradition of hospitality to forced migrants, dating back to the 7th century when the Abyssinian king, Negash, provided sanctuary to Muslim converts facing persecution in Mecca. It is now one of the largest refugee-hosting nations in the world, and the third largest in Africa. Still, at times there have been rivalries between Ethiopian natives and new arrivals, including in the Gambella region, which has a large population of refugees from South Sudan. Nearly all of the registered refugees and asylum seekers in Ethiopia originate from neighboring states including South Sudan (48 percent), Somalia (27 percent), Eritrea (19 percent), and Sudan (6 percent).

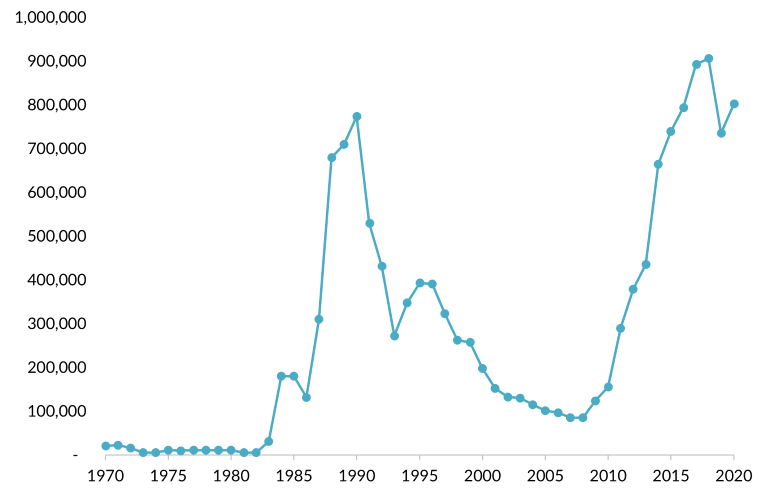

The number of humanitarian migrants in Ethiopia grew dramatically in the late 1980s and then again in the decade since 2010 (see Figure 2). Due to increasing arrivals, the number of refugee camps in Ethiopia grew from eight in 2009 to 26 by 2014. In 2021, amid the conflict involving regional militants, two refugee camps in the northern Tigray region hosting mostly Eritrean refugees were closed, and human-rights advocates have reported that Tigrayan and Eritrean forces committed horrific abuses against those camps’ residents.

Figure 3. Humanitarian Migrants Residing in Ethiopia, 1970-2020

Note: Data refer to the number of refugees under UNHCR protection, asylum seekers, and others of concern to UNHCR as of the end of the year.

Source: UNHCR, “Refugee Data Finder,” accessed September 13, 2021, available online.

Many refugees living in Ethiopia have expressed interest in onward movement, such as towards Israel or Europe. For Eritreans, the factors affecting their departure from Ethiopian refugee camps are complex and can include safety, familial responsibilities, general satisfaction with life in Ethiopia, as well as the existence of connections abroad that could support them on the journey to a third country. General hopelessness, access to work and educational opportunities, a so-called culture of migration, and accessibility of traffickers can also play a role.

Refugee Response Initiative

Ethiopia is one of the 15 pilot countries to implement the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF), a global shared commitment to improving the lives of refugees and host communities in a coordinated way. Its objectives are easing pressure on host countries, improving refugee self-reliance, expanding access to resettlement in third countries, and creating conditions in countries of origin for voluntary return. Seven of these pilot countries are in Africa.

Ethiopia launched the CRRF in 2017 and has made considerable progress on registration of refugees and including them in basic services such as education and health care, as well as improving legal regimes. However, the rollout of livelihood and job-creation schemes has been slower, due in part to lack of funding, poor coordination frameworks, and absence of grassroots stakeholder participation. Huge monetary investments are required to implement the CRRF. Yet the funds made available by international partners have not been adequate to carry out many programs, especially initiatives to promote self-reliance.

Return and Reintegration

Return migration to Ethiopia has increased over recent years, often involuntarily as larger numbers of migrants have traveled irregularly to find work and as migration policies in destination countries such as Saudi Arabia have become more restrictive. Providing necessary reintegration support has become an area of concern for the Ethiopian government, public, and development partners. This concern heightened following the massive forced repatriation of irregular Ethiopian migrants from Saudi Arabia in 2013 and 2014, during which approximately 170,000 Ethiopians were deported. Returns have continued, and an additional 415,000 Ethiopians were returned from Saudi Arabia between November 2017 and July 2021, according to the Ethiopian government.

Migrants expelled from Saudi Arabia have returned with complex economic and psychosocial problems; many were victims of trafficking, reported harsh treatment, and have lost most or all their belongings. In particular, while in detention, many migrants reportedly had no or limited access to water, toilets, food, or privacy. Recently, returned migrants from Tigray—who accounted for 40 percent of returnees between November 2020 and June 2021—have remained stranded in the capital due to conflict in their native region.

Many returnees have received immediate humanitarian assistance from the government and aid groups, including health care, shelter, and transportation. However, the government has historically faced challenges reintegrating returnees into the labor market and their communities, as well as reunifying them with their families. Lack of funds and skills makes it harder for returnees to re-enter the local labor market.

Repatriation can also dramatically impact the families who rely on migrants’ remittances. Often, returnees may migrate again, even if their first experience was not a positive one. Evidence demonstrates that remigration is often the result of lack of effective reintegration.

Migration’s Role in Ethiopian Development Policy

Ethiopia is one of the top financial remittance destinations in sub-Saharan Africa, and these transfers, which have accounted for approximately 5 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) according to the National Bank of Ethiopia, have become an important source of foreign currency and livelihood for many families. Flows have surged dramatically over the last two decades: the Ethiopian Diaspora Agency revealed that even amid the COVID-19 pandemic, official remittances in fiscal year (FY) 2021 reached U.S. $3.6 billion, up from U.S. $104 million in FY 2000. The actual amount of money remitted is estimated to be much larger, since informal transfers, which are estimated to be sizable in Ethiopia, are not captured in official data. Informal transfers are typical from the prime emigrant destinations of Saudi Arabi and South Africa.

Since the early 2000s, the Ethiopian government has shown renewed interest in engaging the diaspora. Ethiopians living abroad were regarded as development partners in the 2011-2015 Growth and Transformation Plan, which referred to them as an “opportunity” to attain development goals. This followed the government’s formation in 2002 of the Ethiopian Expatriate Affairs General Directorate, which has since been replaced by the Diaspora Engagement Affairs General Directorate, under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 2018, the ministry also established an Ethiopian Diaspora Agency. These offices have been charged with working with the diaspora and ensuring their issues are integrated in development projects. The government has also added labor attachés to many diplomatic missions.

The government has incentivized investment by the diaspora through tax and custom measures allowing emigrants and foreign nationals of Ethiopian descent to open foreign-currency bank accounts in Ethiopian banks, and at one point even provided them with free plots of land in the country. It has also provided Ethiopian Origin ID Cards, commonly called yellow cards, for individuals who have changed nationalities. The card entitles holders to enjoy all privileges offered to Ethiopians abroad, including the right to enter the country without a visa.

For many years under the TPLF, however, the driving motivation behind Ethiopia’s diaspora policies was political, rather than development-focused, and did not clearly recognize the diaspora’s diversity. Members of the diaspora tended to support opposition parties, most clearly during and after the contested 2005 election which led to large-scale unrest and crackdowns by police. As a result, the government implicitly saw the diaspora as opponents or potential threats, and expatriate Ethiopians meanwhile often remained skeptical about investing their savings, skills, and knowledge acquired abroad.

Government efforts led to the development of a comprehensive diaspora policy in 2013 which for the first time promised voting rights for nationals living abroad and roles as election observers. As of this writing, these reforms had not been implemented, however, suggesting the need for fundamental reform in governance, including overcoming distrust between the government and the diaspora.

A New Era for Diaspora Relations?

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s 2018 election suggested a reinvigorated era in diaspora-government relations, after three decades of distrust while TPLF leaders were in power. His government’s political reforms have mostly been embraced by diaspora members, who have increasingly engaged in Ethiopia’s economic and political spheres. Indeed, the diaspora played an important role in bringing about political reform in Ethiopia by mobilizing activity online and working with reformist leaders. Since Abiy’s election, many Ethiopians abroad have shown support by sending remittances through the banking system, lobbying Western powers to back the government, organizing demonstrations abroad, and supporting projects such as the massive Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and a large-scale tree-planting initiative. This is in contrast to earlier eras, when wealthy members of the diaspora campaigned against sending remittances through the banking system, avoided the state-owned Ethiopian Airlines, and lobbied in support of economic sanctions on Ethiopia.

Still, the country is deeply divided along ethnic and religious lines, and so is the diaspora. This divide has become more pronounced since the conflict in the Tigray region began.

The Abiy era has prompted some reforms for Ethiopians abroad, particularly in the financial and banking sector. Foreign nationals in the diaspora are now able to invest and lend money in Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Diaspora Trust Fund was established in 2018 and in two years has collected more than U.S. $7.5 million to distribute health-care supplies, provide services for children with special needs, and other projects. In 2021, members of the diaspora contributed tens of millions more for the military, to support rehabilitation efforts in Tigray, and other projects, according to Selamawit Dawit, the director-general of the Ethiopian Diaspora Agency.

Decades of Evolving Migration Flows

Over the last 50 years, Ethiopia has transitioned from a country whose migrants were largely forcibly displaced to ones with significant financial and political power in their homeland. While still a source of a considerable number of refugees, Ethiopia is also the origin for large numbers of labor migrants in both low- and high-skill sectors, and increasingly playing a pivotal role in regional migration through Africa.

The country still has a ways to go to fully capitalize on its growing diaspora. Remittances can stimulate local economies, notably in the tourism, agriculture, business, and education sectors. But in Ethiopia, this potential has been largely constrained by barriers such as poor entrepreneurship skills, low productivity, and weak institutional support. Diaspora engagement has increasingly been a focus of the government, and ongoing attention to the growing power of emigrants and their descendants could be transformative for Ethiopia’s future. Migration and remittances have had significant positive impacts, but they can also foster dependency, family disputes, and corruption. To maximize the benefits, local and regional governments could design strategies to further channel funds into investment and reduce the negative impacts, while the national government could take steps to improve the money transfer market and support mobile money transfer technologies.

The country still also faces serious security challenges that could propel future displacement, as the conflict in the Tigray region underscores. Maintaining stability, harnessing the power of its diaspora, and ensuring more regularized pathways for labor emigrants are key challenges for Ethiopia looking forward.

Sources

Adepoju, Aderanti. 1995. Migration in Africa: An Overview. In The Migration Experience in Africa, eds. Jonathan Baker and Tade Akin Aina. Uppsala, Sweden: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

Adugna, Girmachew. 2019. Migration Patterns and Emigrants’ Transnational Activities: Comparative Findings from Two Migrant Origin Areas in Ethiopia. Comparative Migration Studies 7 (1): 1-28. Available online.

---. 2021. Understanding the Forced Repatriation of Ethiopian Migrant Workers from the Middle East. Working Paper No. 2021/8, Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS), Toronto, July 2021. Available online.

Andargachew, Ephrem. 2021. Ethiopia: Diaspora Contributing Tremendously in the Financial Sector. Ethiopian Herald, July 6, 2021. Available online.

Bariagaber, Assefaw. 1997. Political Violence and the Uprooted in the Horn of Africa: A Study of Refugee Flows from Ethiopia. Journal of Black Studies 28 (1): 26-42.

Chacko, Elizabeth and Peter H. Gebre. 2013. Leveraging the Diaspora for Development: Lessons from Ethiopia. GeoJournal 78 (3): 495-505.

De Regt, Marina and Medareshaw Tafesse. 2016. Deported Before Experiencing the Good Sides of Migration: Ethiopians Returning from Saudi Arabia. African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal 9 (2): 228-42. Available online.

Ethiopian Diaspora Trust Fund. N.d. Active Projects. Accessed September 24, 2021. Available online.

Ethiopian Embassy in Washington, D.C. 2021. The Spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ethiopia, Press Briefing Summary. News release, July 29, 2021. Available online.

Ezra, Markos. 2003. Environmental Vulnerability, Rural Poverty, and Migration in Ethiopia: A Contextual Analysis. Genus 59 (3): 63-91.

Frouws, Bram and Christopher Horwood. 2017. Smuggled South: An Updated Overview of Mixed Migration from the Horn of Africa to Southern Africa with Specific Focus on Protections Risks, Human Smuggling and Trafficking. RMMS Briefing Paper No. 3, Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat, Nairobi, March 2017. Available online.

Horwood, Christopher. 2009. In Pursuit of the Southern Dream: Victims of Necessity: Assessment of the Irregular Movement of Men from East Africa and the Horn to South Africa. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. Available online.

Horwood, Christopher and Roberto Fori. 2019. Everyone’s Prey: Kidnapping and Extortionate Detention in Mixed Migration. Geneva: Mixed Migration Centre. Available online.

Isaac, Leon. 2017. Scaling Up Formal Remittances in Ethiopia. Brussels: International Organization for Migration (IOM) Regional Office for the EEA, the EU, and NATO. Available online.

Kanko, Teshome D., Ajay Bailey, and Charles H. Teller. 2013. Irregular Migration: Causes and Consequences of Young Adult Migration from Southern Ethiopia to South Africa. Paper presented at the XXVII International Union for the Scientific Study of Population International Population Conference, Busan, South Korea, August 26-31, 2013. Available online.

Kaplan, Steven. 2005. Tama Galut Etiopiya: The Ethiopian Exile Is Over. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 14 (2/3): 381-96.

Kloos, Helmut. 1990. Health Aspects of Resettlement in Ethiopia. Social Science & Medicine 30 (6): 643-56.

Kuschminder, Katie. 2017. Reintegration Strategies. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kuschminder, Katie and Melissa Siegel. 2011. Understanding Ethiopian Diaspora Engagement Policy. UNU-Merit Working Paper No. 2011-040, Maastricht University Graduate School of Governance and UNU-Merit, Maastricht, Netherlands, September 2010. Available online.

---. 2014. Migration and Development: A World in Motion Ethiopia Country Report. Maastricht, Netherlands: Maastricht University Graduate School of Governance. Available online.

Lyons, Terrence. 2007. Conflict-Generated Diasporas and Transnational Politics in Ethiopia. Conflict, Security & Development 7 (4): 529-49.

Mubanga, Christopher Kapangalwendo. 2017. Protecting Eritrean Refugees' Access to Basic Human Rights in Ethiopia: An Analysis of Ethiopian Refugee Law. Dissertation submitted for the degree of Master of Laws at the University of South Africa, Pretoria, August 2017. Available online.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2019. Are the Characteristics and Scope of African Migration Outside of the Continent Changing? Migration Data Brief No. 5, OECD and Agence française de développement (AFD), Paris, June 2019. Available online.

Roeder, Amy. 2012. Transforming Ethiopia’s Health Care System from the Ground Up. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, August 29, 2012. Available online.

Smith, Lahra. 2007. Political Violence and Democratic Uncertainty in Ethiopia. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace. Available online.

Sturge, Georgina and Nassim Majidi. 2017. Eritreans Find Refuge in Ethiopia but No Incentive to Remain. Refugees Deeply, April 24, 2017. Available online.

Terrazas, Aaron Matteo. 2007. Beyond Regional Circularity: The Emergence of an Ethiopian Diaspora. Migration Information Source, June 1, 2007. Available online.

Tilahun, Tsegaye. 2021. Ethiopia Secures 3.6 Bln. Usd From Remittance. Ethiopian Herald, August 6, 2021. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2016. Study on the Onward Movements of Refugees and Asylum-Seekers from Ethiopia. Geneva: UNHCR and Danish Refugee Council. Available online.

---. 2021. Operational Data Portal: Ethiopia. Updated August 31, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Response to Internal Displacement in Ethiopia: January to June 2021. Fact Sheet, UNHCR, Addis Ababa, September 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Refugee Data Finder. Accessed September 13, 2021. Available online.

United Nations Population Division. 2020. International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin. Available online.

Zewdu, Girmachew Adugna. 2014. The Impact of Migration and Remittances on Home Communities in Ethiopia. Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, May 2014. Available online.

---. 2018. Irregular Migration, Informal Remittances: Evidence from Ethiopian Villages. GeoJournal 83 (5): 1019-34.