You are here

The EU-Turkey Deal, Five Years On: A Frayed and Controversial but Enduring Blueprint

Migrants arrive in Greece on a crowded boat from Turkey. (Photo: © UNHCR/Achilleas Zavallis)

The onset of civil war in Syria in 2011 and other global crises forced millions of people to flee to neighboring states and Europe. More than 1 million asylum seekers and other migrants from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, and countries farther afield such as Pakistan and Nigeria arrived in European Union countries in 2015, the most ever recorded in a single year. With the bloc lacking an effective mechanism to share the burden of responding to these asylum claims, Member States in the south and east faced a disproportionate impact as arrivals surged and continued at significant rates into 2016. The migration challenge quickly became continental, threatening to undermine the decades-long project of European integration and shatter the notion of Europe as a singular entity that could speak with one voice.

In March 2016, the European Union entered into a landmark agreement with Turkey, through which hundreds of thousands of migrants had transited to reach EU soil, to limit the number of asylum seeker arrivals. Irregular migrants attempting to enter Greece would be returned to Turkey, and Ankara would take steps to prevent new migratory routes from opening. In exchange, the European Union agreed to resettle Syrian refugees from Turkey on a one-to-one basis, reduce visa restrictions for Turkish citizens, pay 6 billion euros in aid to Turkey for Syrian migrant communities, update the customs union, and re-energize stalled talks regarding Turkey’s accession to the European Union. Turkey was at the time the largest refugee-hosting country in the world—a position it continues to hold—with the vast majority of its approximately 3 million refugees coming from Syria, though there were also large numbers of Iraqis, Iranians, and Afghans.

The deal had multiple ambitions: Most clearly, it was intended to reduce the pressure on Europe’s borders and dissuade future asylum seekers and economic migrants from making the sometimes perilous journey. Just as importantly, it was meant to send a signal—both externally and within the bloc—that EU Member States could stand united on issues that struck at the core of the union. The arrangement was just one of several efforts to slow migration to Europe at the time—equally notable were restrictions along the Western Balkans migratory route.

Despite significant and sustained criticism of the EU-Turkey deal from human-rights advocates and humanitarian organizations, leaders on both sides have continued to show interest in maintaining at least some version of its central commitments. Renewed tensions in spring 2020, when Ankara threatened to let hundreds of thousands of migrants into Greece before backing off, showed just how much the European Union has relied on its eastern neighbor as a bulwark. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said this month that the deal “remains valid and has brought positive results.”

As the 2020 standoff signaled, the European Union and Turkey remain in an uncomfortable partnership, separated by politics as much as geography. While the arrangement has showed signs of fraying, with particular frustration from Turkey, its centerpiece promise has held—at least for Europe. The number of arriving migrants and asylum seekers has plunged, in part as a result of the deal, and the bloc has remained intact. With the last of the 6 billion euros in aid committed in December, there has been resurgent interest in renewing the arrangement. And despite its challenges, the EU-Turkey statement has gone on to become a blueprint for Europe’s strategy of externalizing migration management to its neighbors. This article explores the achievements and challenges of the 2016 agreement and its costs in the process.

A New Deal for an Old Relationship

European countries and Turkey had migration relationships long before the advent of the EU-Turkey deal. Germany, Italy, and Spain had previously entered into bilateral migration agreements with Turkey, though these were mainly labor pacts to bring Turkish workers to Europe to stimulate post-War World II economies.

The 2016 deal was different. Not only was the size of the migration challenge much greater than any Europe had seen before, but it was the clearest instance of coordinated EU action to employ its neighbors to prevent would-be asylum seekers and other migrants from arriving.

Europe’s motives were obvious: The bloc was struggling to process large numbers of asylum seekers and was finding burden-sharing among Member States far more difficult to achieve than the Common European Asylum System imagined when it began in 1999.

Turkey’s rationale for the deal was at least partly based on the expectation, shared by much of the international community, that the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad would not last long. In the early stages of Syria’s civil war, Turkey declared an open-door policy and offered temporary protection for Syrians fleeing the fighting. However, the persistence of the Syrian conflict and the growing number of refugees created challenges, and since 2016 Turkey has tightened its eastern borders. As Assad has consolidated his position, it has become clear that most refugees will not return to Syria soon, casting doubt on the temporary nature of their stay. In March 2021, nearly 3.7 million Syrian refugees lived in Turkey, an increase of nearly 1 million since the 2016 agreement was signed. The deal also offered Turkey action on its long-sought ambitions of closer ties with Europe, including EU ascension. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan may have also been motivated by domestic political pressures; just months later, his government would repel a coup attempt.

Did the Deal Work?

The EU-Turkey accord was criticized for permitting Europe to shrug off its humanitarian protection responsibilities by having Turkey bottle up desperate asylum seekers. Yet many in Europe and elsewhere consider it to have been successful on at least some measures. German Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose country received more than 1 million asylum seekers in 2015 and 2016, has praised the deal’s effectiveness in stemming irregular arrivals and suggested it could be a model pact. Leaders on both sides have discussed renewing it, with EU top foreign policy official Josep Borrell in March claiming, “in the future, some kind of agreement of this type has to be done.” Renewing and “revisiting” it “is a must and in the interest of all the parties,” Turkish Deputy Foreign Minister Faruk Kaymakci agreed.

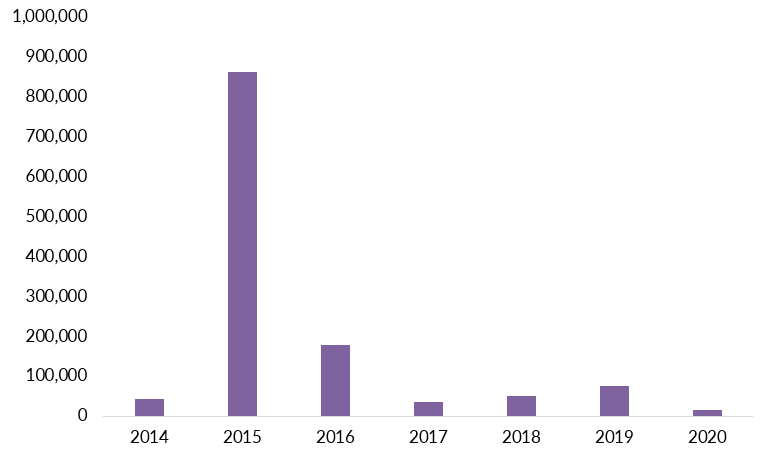

In numerical terms, the data are clear. At the peak of the crisis, Italy and Greece were asylum seekers’ main arrival points in Europe, with more than 861,000 arrivals in Greece in 2015. The number dropped to 36,000 the year after the deal was signed, before climbing again to nearly 75,000 in 2019 (see Figure 1). Additionally, the number of dead and missing migrants in the Aegean Sea, which separates Turkey from Greece, decreased from 441 cases in 2016 to 102 in 2020. In the immediate aftermath of the deal, the European Union ramped up asylum service staff, relocated thousands of asylum seekers, and provided monetary support to Greece.

Figure 1. Migrant Arrivals in Greece, 2014-20

Source: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Operational Portal: Refugee Situations, Mediterranean Situation, Greece,” last updated March 14, 2021, available online.

The EU-Turkey deal is not solely responsible for the dramatic drop in overall arrivals. Countries in the Western Balkans also closed access to migrants, barring a well-trod land route into Europe. Still, the EU-Turkey arrangement was the most visible symbol of concerted action to limit migration.

Success has been more mixed in Turkey, where Erdoğan’s government has claimed that key elements of the deal were not met. The European Union agreed to provide 6 billion euros in humanitarian assistance, education, health care, municipal infrastructure, and socioeconomic support for Syrian refugees in Turkey between 2016 and 2019. Although the European Union says the full amount has been allocated and more than 4 billion euros have been disbursed, the Turkish government has taken issue with the pace and manner of the payments, which have gone to refugee-serving organizations rather than government accounts. In 2020, the European Union committed to providing an additional 485 million euros to see some programs continue through 2021.

The promise of one-to-one resettlements also has appeared smaller than one might have expected; from March 2016 to March 2021, slightly more than 28,000 Syrian refugees were resettled in the European Union from Turkey, far short of the maximum 72,000 outlined in the deal. Discussions of bringing Turkey into the European Union and easing visa processes for Turks have meanwhile mostly stalled, as Erdoğan’s government has turned increasingly authoritarian.

In an effort to display its discontent, the Turkish government in spring 2020 allowed migrants to pass through its territory and reach the Greek border, where asylum seekers were repelled, sometimes with force. In response, Greece suspended asylum applications for a month, deported migrants entering illegally, and deployed its military to the border. In a statement, Greece claimed that “Turkey, instead of curbing migrant and refugee smuggling networks, has become a smuggler itself.” Erdoğan, who said at the time that he had rejected an EU offer of 1 billion euros in additional aid, was accused of using asylum seekers as leverage to extract additional money, assistance, and other political concessions from Europe.

Some corners of the international community have remained skeptical of the arrangement. Most criticisms stem from whether Turkey meets the standard for effective protection of asylum seekers. The 2016 deal promised the creation of an EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey, which is a joint coordination mechanism that provides modest financial and other support to more than 1.8 million refugees. But many Syrians remain in difficult conditions, often relying on low wages in the informal sector, lacking social supports, and with large numbers of Syrian children not enrolled in school. Meanwhile, asylum seekers who reach Greece have often been kept in overcrowded camps. In March, Amnesty International described the deal’s history as being one of “failed policies which have resulted in tens of thousands of people being forced to stay in inhumane conditions on the Greek islands, and put refugees at risk by forcing them to stay in Turkey.”

The Agreement’s Legacy

The EU-Turkey deal was notable for the way that it shifted significant responsibility for managing European migration management to Turkey. It was also one of the first instances of the European Union taking a stance on migration as a bloc. While Member States had disjointed responses to earlier influxes prompted by the Arab Spring, this deal was a comprehensive and uniform reaction in which its 28 Member States spoke as one.

In the process, the accord set the tone for future European migration diplomacy, even outside EU auspices. Since 2016, multiple bilateral migration agreements have been implemented to externalize aspects of European migration management, including the 2017 Italy-Libya Memorandum of Understanding. Italy in 2008 had signed a “friendship” agreement with the regime of leader Muammar Gaddafi to stem irregular migrant arrivals, and a second agreement in 2011 with Libya’s post-revolution National Transitional Council. The 2017 agreement proved different because, among other features, this time the Italian government and the European Union provided the Libyan coast guard with boats, equipment, and training to patrol Libya’s waters and deter smugglers from taking migrants across the Mediterranean. In 2017 alone, around 20,000 people were intercepted by the Libyan coast guard and taken back to detention centers in Libya.

The EU-Turkey agreement also served to reignite deals between Morocco and Spain, which had cooperated on migration issues in the past. Madrid convinced the European Union to provide 140 million euros for measures such as speedboats and staff to enforce Morocco’s migration controls, and offered up an additional 30 million euros of its own. Subsequently, fewer than half as many people arrived in Spain via sea in 2019 compared to the previous year.

Like the EU-Turkey agreement, these deals have been criticized by human-rights groups, which consider them ways to circumvent international humanitarian obligations. Advocates contend these types of arrangements make Europe complicit in the abuse of migrants in other countries. For instance, Human Rights Watch said in 2019 that Italy “shares responsibility” for abuses committed against migrants in Libya.

A European Migration System?

Despite the European Union’s ambitions to combat the erosion of European integration and bolster solidarity, the bloc has continued to battle fragmentation. In June 2016, just months after the EU-Turkey deal was signed, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. Other Eurosceptic movements in Greece, the Netherlands, and elsewhere were given new life, at least partly due to anxieties about migration.

Still, institutional reforms across the bloc suggest that Europe continues to aspire to manage migration on a continent-wide basis. In September 2020, the European Commission unveiled its Pact on Migration and Asylum, which seeks to streamline the EU migration management system and enhance solidarity across Member States with more sharing of responsibility, improved and quicker migration and asylum procedures, and appeals for relocating asylum seekers and returning those whose applications have failed. The pact also proposes to reform the Common European Asylum System and strengthen the European Asylum Support Office to increase Member States’ cooperation. The European Border and Coast Guard Agency, Frontex, has also grown significantly since the 2015-16 surge in arrivals, showing the bloc’s commitment to EU-wide border management.

Meanwhile, the number of asylum applications decreased from more than 600,000 over the last six months of 2016 to slightly more than 250,000 over the second half of 2020, although these numbers were likely affected by the global slowdown during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tensions With and within Turkey

If the goal of the agreement was to usher in a period of European-Turkish harmony, it did not deliver. Erdoğan’s 2020 move to temporarily reopen Turkey’s border into Europe was a sign of his government’s willingness to leverage its geopolitical position as a buffer between Syria and Europe.

Recent years have also seen hostility from Turkish host communities towards Syrians. While this animosity did not emerge as swiftly or as extremely as it did in some European countries, it certainly became an issue. Violence between host communities and Syrian refugees increased threefold from 2016 to 2017, and has recurred at various points since. Many Turks blame refugees for stealing jobs and carrying out terror attacks. Additionally, although many Syrians in Turkey enjoy significant rights and access to services, their status derives from the country’s temporary protection regime, not international refugee law. As such, their status could potentially be revoked.

Many advocacy organizations doubt that Turkey can be considered a safe country in which refugees and asylum seekers are given adequate care and protection from being sent back to Syria, as the deal contends. Among other issues, rights groups and journalists have documented cases in which people were forced to return to Syria, often after abuse and detention. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch report that refugees have been deported back to Syria under the guise of voluntary repatriation, as part of efforts to create a “safe zone” in the country.

Europe Since the Crisis

Though European countries are no longer facing major asylum application backlogs, the resonance of the 2015-16 crisis can be seen in some of their politics and in their continued approach to migration. When Turkey opened its border in 2020, the bloc came out in full force to support Greece, which von der Leyen called the continent’s “shield,” offering hundreds of millions of euros of aid to Greece and once again presenting a united front.

On the fifth anniversary of the EU-Turkey deal, leaders in Europe and Turkey alike suggested the agreement would likely endure in some form. In late March, Erdoğan’s chief advisor Ibrahim Kalin argued that amending and renewing the deal could “give the Syrian people a sense of hope and trust.” Von der Leyen and European Council President Charles Michel met with Erdoğan in Ankara on April 6, and afterwards signaled that additional funding for Turkey was forthcoming, so long as the country continued upholding its end of the agreement. “I am very much committed to ensuring the continuity of European funding in this area,” said von der Leyen. “Our support is a sign of Europe's solidarity to Turkey and an investment in shared stability.”

Looking ahead, creating new frameworks for governing migration will be a defining challenge of the 21st century. Intentionally or not, the European Union’s 2016 agreement with Turkey formed a template for these agreements of the future. By rallying the bloc’s support behind a single pact and relying on neighboring countries as barriers, the agreement marked a turning point, and variations on its central premise are likely to be unveiled and debated for years to come. The costs have been high, both in terms of the political capital expended and the poor treatment of migrants trapped along the way. But the key parameters have been set, and they are unlikely to be undone as quickly as they were erected.

Sources

Amnesty International. 2016. No Safe Refuge: Asylum-Seekers and Refugees Denied Effective Protection in Turkey. London: Amnesty International. Available online.

---. 2021. EU: Anniversary of Turkey Deal Offers Warning Against Further Dangerous Migration Deals. News release, March 12, 2021. Available online.

Associated Press. 2020. Rights Groups to Italy: Don’t Renew Migrant Deal with Libya. Associated Press, January 31, 2020. Available online.

Benvenuti, Bianca. 2017. The Migration Paradox and EU-Turkey Relations. Working paper, Istituto Affari Internazional, Rome, January 2017. Available online.

Chin, Rita. 2007. The Guest Worker Question in Postwar Germany. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Collett, Elizabeth. 2016. The Paradox of the EU-Turkey Refugee Deal. Migration Policy Institute commentary, March 2016. Available online.

Dinçer, Osman Bahadır et al. 2013. Turkey and Syrian Refugees: The Limits of Hospitality. Washington, DC, and Ankara: Brookings Institution and International Strategic Research Organization (USAK). Available online.

European Commission. 2018. EU Turkey Statement: Two Years On. Fact sheet, European Commission Department of Home Affairs, Brussels, April 2018. Available online.

---. 2020. Migration and Asylum Package: New Pact on Migration and Asylum Documents. September 23, 2020. Available online.

---. 2021. Statement by President von der Leyen at the Joint Press Conference with President Michel, Following the Videoconference of the Members of the European Council. Press release, March 25, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Statement by President von der Leyen following the meeting with Turkish President Erdoğan. Press release, April 6, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Common European Asylum System. Accessed March 19, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. The EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey. Accessed February 24, 2021. Available online.

European Council. 2016. EU-Turkey Statement. Press release, March 18, 2016. Available online.

European Union External Action Service. 2021. Remarks by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell at the Press Conference. March 15, 2021. Available online.

Eurostat. 2021. Asylum and First Time Asylum Applicants by Citizenship, Age and Sex - Monthly Data (Rounded). Last updated March 3, 2021. Available online.

Gercek, Burcin. 2021. Turkey Begins Push to Renew 2016 EU Deal. Agence France-Presse, March 17, 2021. Available online.

German Federal Government. 2021. Fifth Anniversary of the EU-Turkey Statement. News release, March 18, 2021. Available online.

Hinze, Annika Marlen. 2013. Turkish Berlin. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Human Rights Watch. 2016. Q&A: Why the EU-Turkey Migration Deal Is No Blueprint. Blog post, November 14, 2016. Available online.

Kalin, Ibrahim. 2021. An Updated Migration Deal Can Revitalise Turkey-EU Relations. European Council on Foreign Relations, March 19, 2021. Available online.

Kirişci, Kemal. 2014. Syrian Refugees and Turkey's Challenges: Going beyond Hospitality. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. Available online.

Kirişci, Kemal and M. Murat Erdoğan. 2020. Turkey and COVID-19: Don't Forget Refugees. Blog post, Brookings Institution, April 20, 2020. Available online.

Makovsky, Alan. 2019. Turkey’s Refugee Dilemma: Tiptoeing toward Integration. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. Available online.

Martín, María and Lucía Abellán. 2019. Spain and Morocco Reach Deal to Curb Irregular Migration Flows. El País, February 21, 2019. Available online.

Nadeau, Barbie Latza. 2011. Thousands of Refugees Fleeing North Africa. Newsweek, June 12, 2011. Available online.

Nielsen, Selin Yıldız. 2016. Perceptions between Syrian Refugees and Their Host Community. Turkish Policy Quarterly 15 (3): 99-106. Available online.

Palm, Anja. 2017. The Italy-Libya Memorandum of Understanding: The Baseline of a Policy Approach Aimed at Closing All Doors to Europe? Blog post, EU Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy, October 2, 2017. Available online.

Pew Research Center. 2016. Number of Refugees to Europe Surges to Record 1.3 Million in 2015. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online.

Relief International. 2020. Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Syrian Refugees in Turkey. N.p.: Relief International. Available online.

Simsek, Ayhan. 2019. Germany: EU-Turkey Refugee Deal Is a Success. Andalou Agency, September 6, 2019. Available online.

Smith, Merrill. 2004. Warehousing Refugees: A Denial of Rights, a Waste of Humanity. Washington: U.S. Committee on Refugees. Available online.

Stevis-Gridneff, Matina. 2020. Greece Suspends Asylum as Turkey Opens Gates for Migrants. The New York Times, March 1, 2020. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2017. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2016. Geneva: UNHCR. Available online.

---. 2020. Dead and Missing at Sea: December 2019. Fact sheet, UNHCR, Geneva, January 2020. Available online.

---. 2021. Europe Situations: Data and Trends – Arrivals and Displaced Populations. Fact sheet, UNHCR, Geneva, January 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Operational Portal: Refugee Situations, Mediterranean Situation, Greece. Last updated March 14, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Operational Portal: Refugee Situations, Syria Regional Refugee Response, Turkey. Last updated March 3, 2021. Available online.