You are here

The EuroMaidan Protests, Corruption, and War in Ukraine: Migration Trends and Ambitions

Public frustration with decades of poor governance and pervasive corruption in Ukraine culminated in the EuroMaidan revolution. (Photo: Ivan Bandura)

Since the outbreak of mass protests against the Yanukovych regime in November 2013, Ukraine has been wracked by violent conflict, with the Russian annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and fighting over two breakaway eastern provinces seeking independence with Russia’s backing. More than 6,400 people had been killed and an estimated 2 million forcibly displaced as of May 2015. This includes 1.3 million internally displaced people and around 700,000 international refugees; asylum claims in Europe increased 13-fold over the previous year to 14,000 in 2014.

In the years leading to the so-called EuroMaidan protests, political instability and pervasive corruption inspired not only a movement for democratization and greater ties with the European Union (EU), but also migration ambitions among a significant portion of the population. Ukraine already has one of the world’s largest diasporas, while the resident population continues to shrink, partly due to ongoing emigration trends.

This article, based on a mixed quantitative and qualitative study conducted from 2010 to 2013 within an EU-funded project in Ukraine, examines the conditions and migration desires preceding and following the EuroMaidan revolution. It then explores the most current migration patterns of humanitarian, economic, and student flows and how the ongoing conflict may impact these trends.

The Political and Social Conditions Leading to EuroMaidan

Decades of poor governance characterized by systemic corruption have fueled political dissatisfaction, social and economic suffering, and emigration among the Ukrainian population since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1992. From the failure of the Orange Revolution in 2004, the subsequent coming to power of the Party of Regions and President Viktor Yanukovych gave rise to a new kleptocracy that almost ruined the country. Corruption in all sectors of society reached new highs, severely undermined the rule of law, prevented necessary foreign investment, held back economic transformation, and frustrated hope for overall improvements in quality of life.

Dissatisfaction and Migration Ambitions

Before the EuroMaidan protest movement, Ukraine experienced a widespread rise in dissatisfaction with public services, the political class, available economic opportunities, and endemic corruption. In a large-scale study on the migration aspirations of Ukrainians, the authors surveyed 2,000 respondents (ages 18-39) from 2010-13 in four regions: two high-emigration areas (one eastern and one western), one low-emigration area in the country’s center, and the capital, Kyiv. The study also included qualitative interviews.

Across all regions surveyed, respondents expressed particular dissatisfaction with policies addressing poverty (82 percent), employment opportunities (76 percent believe it is difficult to find a good job), politicians (75 percent believe they do not serve the people’s best interests), and health care (70 percent believe it is bad or very bad). Furthermore, 46 percent of respondents were dissatisfied with their financial situation. According to a respondent from central Ukraine:

In my opinion, we have very poor quality of life, because there is a lack of everything. The town is small...here is bad health service...and there is nowhere to study and to work too. There is a lack of everything, and we want something better.

Satisfaction with the quality of life in Zbarazh, the region of high emigration in western Ukraine, was particularly low, as described by this interviewee:

Quality of life...quality of life, of course, we have no quality of life; because salaries are low...for example, my salary is enough only to pay for gas, for electricity, but it is not enough for phone.

Corruption, however, stood out as the single most important cause for frustration. More than 80 percent of those surveyed agreed with the statement “there is a lot of corruption in Ukraine.” Indeed, Transparency International ranks Ukraine 142nd out of 174 countries on its Corruption Perceptions Index. People described corruption as a growing, widespread, and highly problematic issue that impacts all aspects of daily life. Few, if any, legal rights—whether going to the hospital, school, university, or the tax office—are realized without paying unofficial fees; state officials, including police officers, constantly extort extra payments. According to a respondent from Zbarazh, “Here in Ukraine everything can be bought either for money or for big money. There is no third option.”

In response to these conditions, people left or wanted to leave the country in large numbers, with 49 percent of respondents expressing the ambition to emigrate. There are an estimated 2 million to 7 million Ukrainian migrants (estimates vary depending on definition, source, year, and season), mostly in Russia and the European Union, and a global Ukrainian diaspora of 5 million to 6 million. Eastern Ukrainians, Russian speakers, and the lower educated generally have headed to Russia, whereas western and more highly educated Ukrainians typically have moved west to the European Union, and in smaller numbers to the United States. Gendered labor markets also determine that men predominantly go east and west, working largely in construction, while women predominantly go south, notably to Italy, where many work as caregivers. In total, the country’s population shrank from 52 million in 1991 to 42.9 million in 2015, according to the State Statistics Service of Ukraine, due to a mix of aging and emigration.

Dissatisfaction with quality of life and economic opportunities combined with the oppressive experience of corruption and the desire to leave defined the country’s conditions and moods in 2013. After months of negotiations, on November 21, 2013 President Yanukovych unexpectedly decided not to sign the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement, which aimed at closer political association and economic integration with the European bloc. But for many Ukrainians, Europe is a synonym for functional public services, rule of law, economic opportunities, and stability. As one respondent said:

The first coming to mind [when I hear the word Europe] is economic stability, good opportunities for education, job [prospects] and all for life. European level of life sounds nice!

When Yanukovych reversed course by suspending the agreement, the hopes of those in favor of a pro-European path were dashed and mass protests erupted. The protests were most visible and culminated on Independence Square in Kyiv, which became known as “EuroMaidan,” in a combination of the words Europe and square.

Aftermath of the EuroMaidan Protests

In late January 2014, the Ukrainian government stepped down and by the end of February Yanukovych had fled to Russia. Following elections in May, Petro Poroshenko became president, presiding over a coalition of democratic and Ukrainian nationalist parties promoting greater independence from Russia and a pro-European, reform agenda. Pro-Russian forces in eastern Ukraine and Crimea opposed these developments, and in March 2014 Russia annexed the Crimean peninsula, while armed conflict erupted in two eastern Ukrainian provinces between Russia-backed and government forces—fighting that continues today. This had four major consequences. First, the successful revolution and subsequent Russian aggression fostered a wave of patriotism and Ukrainian identity and raised hopes that reforms could diminish emigration and the related loss of manpower, skills, and brains.

Second, the war in the east compelled the government to refocus the momentum from reform to defense of the country, slowing political and institutional change and frustrating peoples’ hopes for quick improvement.

Third, despite democratic elections that installed a new government, corruption remains of concern. While elimination of corruption was seen as a main objective of the EuroMaidan protests, nearly half of respondents said they believe corruption has remained at the same level, while 32 percent said it has increased, according to a Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) / Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation (DI) survey.

Lastly, the war in the east has negatively impacted the economy, resulting in millions pushed into poverty. Ukraine’s currency, the hryvnia, plummeted by more than 50 percent against the U.S. dollar in 2014, increasing Ukraine’s real public and private debt burden (mostly denominated in foreign currencies); inflation reached 24.7 percent in 2014, affecting consumer goods and thus hitting the entire population. Tax and fee increases, a hike in energy prices, and spending cuts have resulted in significant wage and benefit cuts and job losses.

Though joy over the revolution remains widespread more than a year later, optimism for further democratization has diminished and economic hardship, skepticism towards the new government, and continuing corruption prevail. More than 84 percent of respondents in the KIIS/DI survey said that their material well-being had deteriorated. While some people talk of a second social revolution, others again turn to emigration.

Post-EuroMaidan Migration

EuroMaidan, the war in the east, and the economic crisis have affected all Ukrainian migration flows, which can be broken down into three main categories: (1) forced migration of international refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) by the war in Donetsk and Lugansk provinces and due to the Russian annexation of Crimea; (2) migration to avoid military conscription; and (3) varied international migration flows of individuals seeking employment or education, including those with some mixed political and economic motivations.

Forced Migration

Nearly 2 million people are estimated to have been displaced, internally and internationally, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). This is 3.5 percent of the total population of Ukraine, and about 26 percent of the population of Donetsk and Lugansk.

Internally Displaced Persons

The Russian annexation of Crimea and subsequent suppression of ethnic Ukrainians and the Tatar Muslim minority resulted in significant displacement. An estimated 20,000 Crimeans had fled to Ukraine, while a further 17,000 were displaced within the Crimean peninsula, according to UNHCR estimates as of October 2014. A study by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) found that many IDPs of Crimean Tatar origin were prompted to flee by tangible fears of repression, including curtailed right to assembly, knowledge of enforced disappearances, persecution of community activists, and the search of homes and mosques by armed men. Many have no desire to return to Crimea if it remains under Russia’s control, and see no quick solution to what has become known as the “Crimean question.”

Furthermore, hundreds of thousands of people have fled to other parts of Ukraine as a result of the fighting in the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics. The vast majority fled the area in May 2014 when the Ukrainian Army stepped up its so-called Anti-Terrorist Operation, and after June 2014 when fighting in the east intensified following an undemocratic and illegal referendum on self-rule. People have continued to leave despite two ceasefires between government forces and pro-Russian separatists and volunteer battalions, notably after fighting resumed in February 2015. Smaller numbers have returned to their homes in periods of reduced violence, including an estimated 2,000 to Debaltseve, the site of a major battle in the fight for Donetsk province.

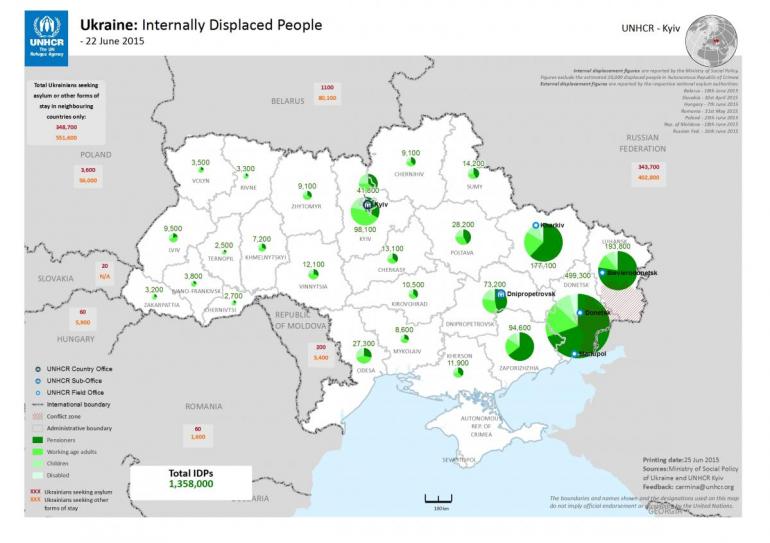

In total, more than 1.3 million people, the vast majority from Donetsk and Lugansk, were considered internally displaced as of late June, according to UNHCR and the Ministry of Social Policy. Many are dispersed within the contested regions, from front-line neighborhoods and villages to cities. IDPs have been displaced to every province (see Figure 1). Patterns, however, have emerged based on their origins within the country: Crimean IDPs have mainly fled to western provinces, while those from eastern Ukraine are mainly displaced within the same region. More than half of all IDPs are registered in the east; state support is limited and most have found private accommodation while 30,000 to 40,000 were living in collective centers as of 2014. Ad hoc observations suggest that initial reception of IDPs was friendly but is now occasionally turning hostile; interestingly, there is evidence that the reallocation of funds from the east to the west has provided a mini-boost to the property market. Developments in the eastern conflict will influence whether people find new livelihoods and integrate in the regions where they are displaced, return to their homes, or engage in further migration.

Figure 1. Internally Displaced Persons in Ukraine, June 2015

Source: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Ukraine: Internally Displaced People—June 22, 2015 (Kyiv: UNHCR, 2015), http://unhcr.org.ua/en/2011-08-26-06-58-56/news-archive/1231-internally-displaced-people.

International Refugees and Asylum Seekers

The continuing conflict has led to a high number of Ukrainians seeking refuge or asylum abroad, mostly in neighboring countries but also elsewhere in Europe. As of early June, the total number of Ukrainians seeking asylum or other forms of legal stay abroad in neighboring countries stood at 900,300, with the majority in Russia (746,500), followed by Belarus (81,200). However, these figures are politicized, inflated, and thus unreliable; Russia has political interests in blaming the Ukrainian government for the conflict and thus presents high numbers of refugees, while many Ukrainian citizens who have been irregularly migrating to Russia for years to work may have exploited the situation and declared themselves refugees to regularize their position. Additionally, in 2014, 14,040 Ukrainians applied for asylum in the European Union, 13 times the number who applied in 2013. Germany had the largest number of applications (2,705), followed by Poland (2,275), Italy (2,080), France (1,415), and Sweden (1,320).

Ukrainians seeking asylum have not found much success in EU Member States, however. Of the 2,985 Ukrainian asylum applications processed in 2014, only 150 were granted full refugee status, while a further 500 were granted other forms of protection. The remainder were rejected, leading to an acceptance rate of just 22 percent. As of March 2015, Poland, among the top three destinations, had not granted refugee status to any of the Ukrainians who arrived in 2014 and the first two months of 2015; 1,700 people were awaiting a decision, while 645 had already been rejected. The Polish Office for Foreigners holds the view that Ukrainians from the eastern part of the country should primarily seek an “internal flight alternative” as they are assumed to be safe in other parts of Ukraine.

Fleeing Army Conscription

As the conflict in the east escalated, the Ukrainian government reinstated a general draft, with the power to conscript men between the ages of 20 and 27. Compulsory military service had been scrapped in late 2013. According to ad hoc evidence and news reports, many young men are using diverse channels of migration to avoid conscription. This includes employment, study, training programs, internships, and other available opportunities. Parents are sending their children abroad to get them out of the danger zone. Others seek shelter internally to avoid military recruiters, often by neglecting to register their new home address with the authorities. In 2014, during partial mobilizations in 13 regions, 85,792 of those summoned did not report to their draft offices and 9,969 were proven to be illegally avoiding service, according to the Ukraine Army.

Mixed International Migration

Meanwhile, Ukrainians continue to migrate for economic and education purposes, notably due to the economic crisis caused by the war.

Access to the European Union

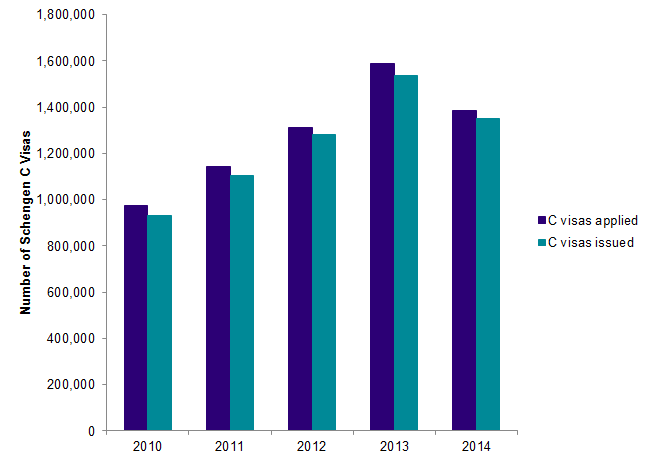

By 2014, Ukrainians ranked fifth amongst top non-EU residents in the European Union (608,193). In 2013, the most recent data available, Ukrainians were the top recipients of first-time residence permits with 237,000, a huge increase from the 150,000 granted in 2011. Currently, Ukrainians are the second most common recipients of Schengen visas of all kinds, after Russians. However, the number of applications for visitor C visas by Ukrainian citizens decreased from 2013 to 2014 and the number of issued visas decreased from 1.54 million in 2013 to 1.35 million in 2014 (see Figure 2). This reflects a decrease in tourism as households have less spending power as well as a decreased demand for foreign labor as a result of the economic downturn in several EU Member States.

Figure 2. Schengen Short-Stay Visa Applications by Ukrainians, 2010-14

Source: European Commission, Fifth Progress Report on Ukraine’s Implementation of the Action Plan on Visa Liberalisation (Brussels: European Commission, 2015), http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/.

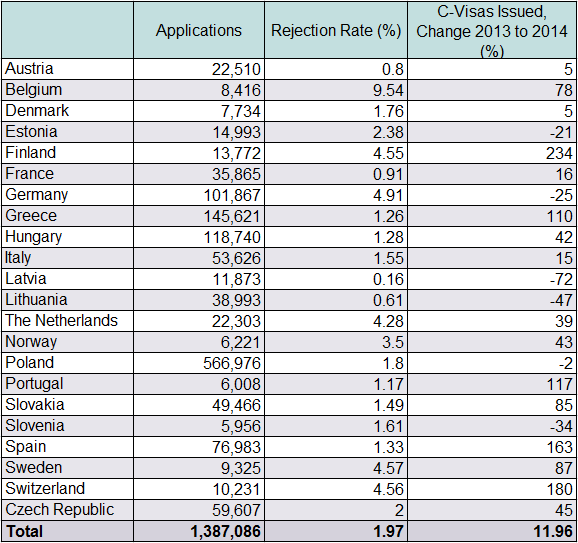

In 2014, Poland received the largest number of Schengen C visa applications from Ukrainians (566,967), and is the first stop for many Ukrainians heading to other EU countries on Polish-issued visas. Greece received the second-largest number (145,621), followed by Hungary (118,740) and Germany (101,867). Finland recorded the largest increase in applications (234 percent), followed by Switzerland (180 percent), Spain (163 percent), Portugal (117 percent), and Greece (110 percent) (see Table 1). The rejection rate is well below the 4.5 percent overall average for EU Member States, implying that Ukrainian applications are largely trusted.

Table 1. Ukrainian Applications for Schengen Short-Stay Visas by Schengen Country, 2014

Source: European Commission, Fifth Progress Report.

In addition, several hundred thousand Ukrainians have accessed the European Union via Schengen medium-stay D visas granted to individuals wanting to reside in one of the Schengen countries for employment, study, or family purposes. Poland issued 276,002 such visas to Ukrainians in 2014—a 43 percent increase from 2013.

Meanwhile, detected irregular border crossings of Ukrainians—60 cases in 2014—remain insignificant and irregular entry using a forged visa or other documents low (56 cases in 2014). However, it is likely that a significant proportion of the 1.5 million Ukrainian Schengen C visa holders seek irregular employment once in the European Union. In 2014, 16,744 unauthorized Ukrainians were detected in the European Union, an increase of around 30 percent from 2013. Recent research by the authors also uncovered evidence of a trade in Polish travel documents facilitating irregular migration.

Finally, Ukrainians have taken advantage of opportunities to acquire foreign nationalities to gain entry to EU Member States. For example, almost 100,000 Ukrainians have been granted Hungarian citizenship based on shared ethnicity.

Economic and Student Migration

The economic crisis and the war have led to a sharp increase in the number of workers and professionals desiring to work abroad. Most first-time EU residence permits are indeed employment permits. In Ukraine, 80 percent of applicants for middle- and senior-management positions would like to work abroad, according to a 2015 HeadHunter study. Almost half (41 percent) indicated the tense political situation, desire to ensure a stable future for their children, and low salaries in Ukraine as motivations. Any option to leave Ukraine is considered, including training, skills development, or an unpromising job abroad.

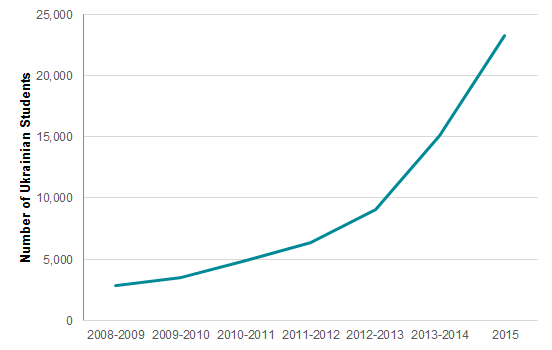

Migration for higher education has also increased. More than 23,000 Ukrainian students had left to study at Polish universities in the first few months of 2015, 50 percent more than in 2014 (see Figure 3). Ukrainians constitute more than half of Poland’s foreign student population. Student migration is facilitated by easy access to Polish student visas; low university fees (800 to 4,000 euros)—similar to rates in Ukraine, but for degrees considered to be of much higher value; better quality education; and the absence of corruption. Agents in Poland and Ukraine promote study in Poland by offering discounts for Ukrainian students. A small-scale survey carried out at Lviv Polytechnic/National University in 2014 revealed that 82 percent of its students want to work abroad, 80 percent want to study abroad, and 44 percent plan to live abroad.

Figure 3. Ukrainian Students in Poland, 2008-15

Source: Yegor Stadnyi, Стадний Є. Кількість студентів-українців за кордоном [Number of Ukrainian students abroad] (Kyiv: Centre of Society Research 2015), www.cedos.org.ua/uk/osvita/56; UNIAN News Agency, “Кількість українських студентів у Польщі за рік зросла ще на 50%,” [Number of Ukrainian students in Poland has increased by 50 percent], April 8, 2015, www.unian.ua/society/1064936-kilkist-ukrajinskih-studentiv-u-polschi-za-rik-zrosla-sche-na-50.html.

Resurgence of the Ukrainian Diaspora

Recent Ukrainian diaspora events in London, Warsaw, and elsewhere have attracted significant crowds, while Ukrainian language schools abroad have gained unprecedented popularity. Inspired by the EuroMaidan protests, united by Russia’s actions, driven by a wish to help the country, and fueled by newcomers, Ukrainian diaspora communities of today engage in more than a sentimental celebration of culture, taking an active role in the reform and reconstruction of the country. The community group London Euromaidan continues its fundraising campaign for the benefit of the Ukrainian Army and victims of the war. Since mid-July 2014, the group has raised approximately GBP 117,000 to purchase more than 30 tons of goods which have already been shipped to Ukraine. In 2014, Ukrainian migrants sent home an estimated USD $9.6 million in remittances, accounting for 5.4 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

Looking Ahead: Changing Migration Patterns and Visa Liberalization

While the fighting in eastern Ukraine continues and political reforms are painfully slow, peoples’ hopes for change have begun to fade and the patriotic surge of the EuroMaidan revolution is faced with the harsh realities of an economy in decline. Once again, international migration from Ukraine is on the rise, though not yet on dramatic levels.

There are reasons to believe that traditional Ukrainian migration patterns are partly going to change, notably the choice of destination. Conventionally, more than half of Ukrainian labor migrants go to Russia. However, the war and Western sanctions have led to an economic crisis in Russia, resulting in job losses and the devaluation of the ruble, rendering labor migration to Russia much less beneficial than before. The role of Russia in Crimea and the eastern provinces and Russia’s anti-Ukrainian propaganda also contribute to its decreasing desirability as a destination. Ukrainians are thus on the lookout for alternatives, which lie mainly in the West.

Whether or not this turns into an uncontrollable movement or a well-managed migration depends to a certain extent on the European Union. As an EU Eastern Partnership country, Ukraine has been in discussions for a visa-free regime with the European bloc for several years. In May 2014, Ukraine launched the second phase of its Visa Liberalization Action Plan (VLAP) which includes implementation of the legislative framework and institutional reforms developed in phase one. If plans for visa liberalization are quickly realized and more legal migration channels opened for students, workers, and the highly skilled, combined with policies that facilitate return and swift reforms, Ukrainian migration may turn out to be a bright spot in the post-EuroMaidan political order.

Sources

Bilan, Yuriy, Yulia Borshchevska, Franck Düvell, Irina Lapshyna, Svitlana Vdovtsova, and Bastian Vollmer. 2012. Perceptions, Imaginations, Life-Satisfaction and Socio-Demography: The Case of Ukraine. EUMagine Project Paper 11, September 24, 2012. Available Online.

Bobinski, Krzysztof. 2014. Kleptocracy: Final Stage of Soviet-Style Socialism. Open Democracy, February 28, 2014. Available Online.

Bullough, Olliver. 2015. Welcome to Ukraine, the most corrupt nation in Europe. The Guardian, February 6, 2015. Available Online.

Delegation of the European Union to Ukraine. 2014. Ukraine: Positive Trends in Schengen Visa Statistics. News release, May 29, 2014. Available Online.

---. 2015. Commission Assesses the Implementation of Visa Liberalization Action Plans by Ukraine and Georgia. News release, May 8, 2015. Available Online.

European Commission (EC). 2015. Fifth Progress Report on Ukraine’s Implementation of the Action Plan on Visa Liberalisation. Brussels: EC, May 8, 2015. Available Online.

European Parliament. 2014. Ukraine: Timeline of Events. News release, updated October 10, 2014. Available Online.

Frontex. 2015. Eastern European Borders Annual Risk Analysis 2015. Warsaw: Frontex. Available Online.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2015. Ukraine IDP Figures Analysis. Accessed June 16, 2015. Available Online.

Jaroszewicz, Marta. 2014. Ukrainians’ EU Migration Prospects. Warsaw: The Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW). Available Online.

Kolesnik, Dmitry. 2015. When Ukrainians Choose Not to Die in a War. CounterPunch, February 8, 2015. Available Online.

Lapshyna, Irina. 2014. Corruption as a Driver of Migration Aspirations: The Case of Ukraine. Economics & Sociology 7 (4): 113-27.

Lapshyna, Irina and Franck Düvell. 2015. Migration, Life Satisfaction, Return and Development: The Case of a Deprived Post-Soviet Country (Ukraine). Migration and Development 4 (2): 291-310.

Leshchenko, Sergii. 2013. Ukraine: Yanukovych's 'Family' Spreads its Tentacles. Open Democracy, January 29, 2013. Available Online.

Luhn, Alec. 2015. The Draft Dodgers of Ukraine. Foreign Policy, February 18, 2015. Available Online.

Lyman, Rick. 2015. Ukrainian Migrants Fleeing Conflict Get a Cool Reception in Europe. The New York Times, May 30, 2015. Available Online.

Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). 2014. Internal Displacement in Ukraine. Kyiv: OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine. Available Online.

Piechal, Tomasz. 2015. Disappointment and Fear – The Public Mood in Ukraine. Warsaw: OSW. Available Online.

Pyatkovska, Oksana. 2014. Brain Drain – Brain Gain: світовий контекст та українські реалії [Brain Drain – Brain Gain: World Context and Ukrainian Realities]. Lviv: МІОК National University, Lviv Polytechnic.

Samaeva, Yulia. 2015. Самаева Ю. Девальвация труда [Devaluation of Labor]. ZN.UA, March 27, 2015. Available Online.

Sputnik International. 2015. Searching for Safety: Ukrainian Asylum Seekers Flee to Europe. Sputnik International, March 26, 2015. Available Online.

Stadnyi, Yegor. 2015. Стадний Є. Кількість студентів-українців за кордоном [Number of Ukrainian Students Abroad]. Kyiv: CEDOS. Available Online.

State Statistics Service of Ukraine. 2015. Population of Ukraine, February 2015. Available Online.

UA Reporter. 2015. Почти 100 тысяч жителей Закарпатья приняли гражданство Венгрии [Almost 100 Thousand Residents of Transcarpathia Took Hungarian Citizenship]. UA Reporter, February 27, 2015. Available Online.

Ukrinform. 2015. Poland Issues Ukrainians 15% Visas More Last Year. Ukrinform, January 17, 2015. Available Online.

UNIAN Information Agency. 2015. Кількість українських студентів у Польщі за рік зросла ще на 50% [Number of Ukrainian Students in Poland has Increased by 50 Percent]. UNIAN Information Agency, April 8, 2015. Available Online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2015. Ukraine: Internally Displaced People, June 22, 2015. Kyiv: UNHCR. Available Online.

---. 2014. Fighting displaces more than half a million people inside Ukraine, hundreds of thousands more into neighbouring countries. (Briefing notes, December 5, 2014). Available Online.

Woehrel, Steven. 2015. Ukraine: Current Issues and U.S. Policy. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available Online.

Zanuda, Anastasia. 2015. Підприємці: корупції в Україні не поменшало [Ukrainian Business Claims there is Not Less Corruption in Ukraine]. BBC Ukraine, April 15, 2015. Available Online.

Zariczniak, Larysa. 2015. The English Ukrainian Diaspora’s Support for Ukraine. Ukrainian Echo, April 17, 2015. Available Online.