Foreign-Born Health-Care Workers in the United States

Source Spotlights are often updated as new data become available. Please click here to find the most recent version of this Spotlight.

Update from the Editor (3/23/2007): This article states that the Nursing Relief for Disadvantaged Areas Act of 1999, which allowed up to 500 foreign nurses to come to the United States annually on H-1C visas to work in medically underserved areas, ended in 2004. However, the U.S. Congress has reauthorized this act (more information here).

Immigration has long been relied upon to offset periodic shortages of health-care workers in the United States. Today, immigrants make up a significant proportion of some health-care occupations.

U.S. health-worker shortages are related to a number of factors, including aging of the nursing workforce, high turnovers of existing health-care workers, and the U.S. educational system not keeping up with demand. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services projects an estimated shortfall of 275,000 full-time registered nurses (RNs) by 2010 and 800,000 by 2020.

Drawing mainly on 2005 American Community Survey (ACS) data from the U.S. Census Bureau, as well as data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, this Spotlight focuses specifically on international health-care worker migration to the United States and provides a demographic and economic profile of foreign-born workers employed in U.S. health-care occupations.

Note: Unless mentioned otherwise, data refer to the population in the labor force ages 18 and older engaged in health-care occupations.

Click on the bullet points below for more information:

- Health-care occupations are projected to account for nearly one in every six newly created jobs in the United States between 2004 and 2014.

- Foreign-born health-care workers can be admitted to the United States under a variety of nonimmigrant, temporary visa categories.

- The United States has discontinued two occupation-specific nonimmigrant visa categories designated for nurses.

- In 2005, 15 percent of all U.S. health-care workers were foreign born.

- About 44 percent of the foreign born in health-care occupations arrived in the United States in 1990 or later.

- One in four doctors (physicians and surgeons) was born abroad.

- Foreign-born health-care workers, regardless of gender, were more likely to be physicians and surgeons as well as nursing and home-care aids than their native-born colleagues.

- Women accounted for more than 70 percent of the foreign born in health-care occupations.

- Nearly 40 percent of all foreign born in health-care occupations were from Asia.

- Foreign-born health-care workers were more likely to have a college education than their native-born counterparts.

- Foreign-born health-care workers had slightly lower labor force participation rates than natives in nearly all occupations.

- In 2005, three-quarters of the foreign born in health-care occupations worked in city centers.

Health-care occupations are projected to account for nearly one in every six newly created jobs in the United States between 2004 and 2014.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) health-care occupations accounted for 10.3 million jobs in 2004. BLS projects that the health-care sector will add another 2.9 million jobs by 2014, which represents 15.4 percent of the total increase of 18.9 million jobs in U.S. employment.

Foreign-born health-care workers can be admitted to the United States under a variety of nonimmigrant, temporary visa categories.

Health-care workers from abroad can come to the United States under a variety of nonoccupation-specific visa categories. These categories include H-1B (specialty occupations), H-2B (nonagricultural workers), H-3 (industiral trainees), TN (NAFTA professionals, includes Mexican or Canadian health-care workers), J-1 (exchange visitors), and O-1 (persons with extraordinary ability in the sciences, etc.).

Doctors with foreign degrees often apply for a J-1 visa to complete their medical education, generally as a medical resident in a U.S. hospital. Doctors may also apply for an H-1B or O-1 visa to complete residency training or to work in the medical field after completing their U.S. residency program.

Foreign-born workers engaged in health-care occupations also can be admitted through permanent immigration channels, such as family or employment-based sponsorship, as well as under humanitarian protection (i.e., refugees and asylees).

The United States has discontinued two occupation-specific nonimmigrant visa categories designated for nurses.

The H-1A visa category, created exclusively for the temporary employment of foreign-trained registered nurses (RNs) under the 1989 Immigration Nursing Relief Act, was phased out in 1995.

|

|

||

|

The H-1C visa for nurses was established as a result of the Nursing Relief for Disadvantaged Areas Act of 1999. It applied only to nurses working in understaffed facilities, in urban and rural areas, that served mostly poor patients. The program ended in 2004.

In 2005, 15 percent of all U.S. health-care workers were foreign born.

According to 2005 ACS, of the 10 million persons engaged in health-care occupations ages 18 and above, 14.5 percent or 1,454,883 were foreign born (see Table 1).

About 44 percent of the foreign born in healthcare occupations arrived in the United States in 1990 or later.

The 1990s was marked by immigration bills that expanded permanent and temporary skilled immigration, including in health-care occupations. Persons who arrived between 1990 and 2005 accounted for 43.5 percent (633,335) of all foreign born engaged in health-care occupations.

One in four doctors (physicians and surgeons) was born abroad.

The foreign born accounted for 26.3 percent of 803,824 physicians and surgeons according to 2005 ACS. This is the highest share of the foreign born among six health-care occupational groups (see Table 1). In contrast, only 10.4 percent of 2.3 million health-care technologists and technicians were foreign born.

Table 1. Total Number of Workers and Percent Foreign born in Health-Care Occupations, 2005 (Excel file)

Foreign-born health-care workers, regardless of gender, were more likely to be physicians and surgeons as well as nursing and home-care aids than their native-born colleagues.

According to ACS 2005 data, 14.5 percent of the foreign born in health-care occupations were physicians and surgeons, 22.3 percent were RNs, and 26.3 percent were nursing and home-care aids, compared to, respectively, 6.9 percent, 24.9 percent, and 18.9 percent of native workers (see Table 2).

Foreign-born men and women were more likely to be physicians and surgeons but had a similar likelihood of being RNs compared to the native born. In contrast, native-born workers were more likely to be engaged as health-care technologists and technicians.

Table 2. Native and Foreign Born by Sex and Health-Care Occupations, 2005 (Excel file)

Women accounted for more than 70 percent of the foreign born in health-care occupations.

Of the 1.45 million foreign born in health-care occupations, women accounted for 72.8 percent according to 2005 ACS. The overwhelming majority of foreign-born registered nurses (RNs) — 88 percent — were women while native-born women made up 91.8 percent of all native-born RNs.

Foreign-born physicians and surgeons were slightly more likely to be women (32.8 percent) than their native-born counterparts (30.6 percent). In contrast, native-born women accounted for a higher share of healthcare technologists and technicians (79.9 percent) than their foreign-born counterparts (70.7 percent).

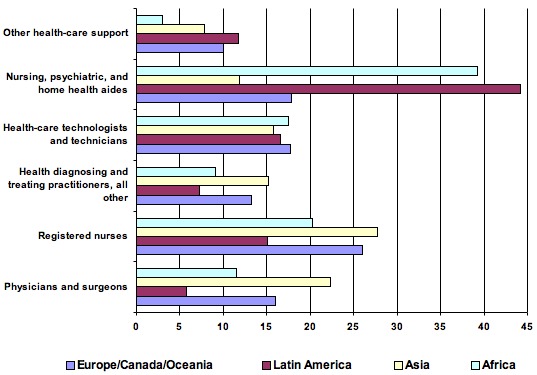

Nearly 40 percent of all foreign born in health-care occupations were from Asia.

In terms of region of birth, ACS 2005 found that Asia accounted for 39.9 percent of all foreign-born health-care workers, followed by Latin America (34.4 percent); Europe, Canada, and Oceania (16.8 percent); and Africa (8.9 percent).

Persons born in Asia were more likely than those from other regions to be RNs (27.6 percent) and physicians and surgeons (22.2 percent) but less likely be engaged as nurses and home health aids (see Figure 1).

In contrast, those from Latin America and Africa were much more likely to be working in nursing and home health-aid occupations (44.1 percent and 39.2 percent, respectively). Persons from Latin America were less likely than the other groups to be physicians and surgeons and RNs.

|

|

||

|

Foreign-born health-care workers were more likely to have a college education than their native-born counterparts.

In four health-care occupational groups — including home health aides and health-care technologists and technicians — the foreign born were much more likely to have a college education than their native colleagues (see Table 3).

Regardless of nativity, nearly all physicians and surgeons had college degrees or higher (see Table 3). More than 85 percent of both native and foreign-born diagnosing and treating practitioners possessed a bachelor's degree and higher.

Table 3. Educational Attainment of Foreign-Born and Native-Born Workers Age 25 and Older (Excel file)

Foreign-born health-care workers had slightly lower labor force participation rates than natives in nearly all occupations.

In 2005, foreign-born physicians and surgeons had the highest labor force participation rate (90.5 percent), while foreign-born nursing and home health-aid workers had the lowest (84.7 percent).

Foreign-born women had lower labor force participation rates than their foreign-born male or native-born female counterparts except in the case of the foreign born in nursing and home health-aid occupations (see Table 4).

Table 4. Labor Force Participation Rates (%) by Nativity, Gender, and Occupational Group (Excel file)

In 2005, three-quarters of the foreign born in health-care occupations worked in city centers.

Relative to natives, foreign-born health-care workers overwhelmingly worked in metropolitan areas: 75.3 percent worked in city centers and another 21.1 percent worked in metro areas excluding the center.

Only 3.6 percent of foreign-born workers were working outside metro areas, compared with 17.9 percent of native-born health-care workers.

Note: data on the geographical distribution of native and foreign-born workers refer to persons who reported working in a reference week and who reported their location of their work.

Additional resources:

American Medical Association. "International Medical Graduates: Practicing Medicine in the U.S." Available online.

American Nurses Association. "International Nursing: United States Licensure Requirements." Available online.

Association of American Medical Colleges. "Visas." Available online.

Heckler, Daniel E. 2005. "Occupational Employment Projections to 2014." Monthly Labor Review, November. Available online.

Lowell, B. Lindsay and Stefka Georgieva Gerova. 2004. "Immigrants and the Healthcare Workforce: Profiles and Shortages." Work and Occupations 31(4): 474-498.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. "Immigration Classifications and Visa Categories." Available online (click Nonimmigrant Visa Classifications).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, Bureau of Health Professions, Health Resources and Services Administration. July 2002. Projected Supply, Demand, and Shortage of Registered Nurses: 2000-2020. Available online.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. March 2004. The Registered Nurse Population: National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses, Preliminary Findings. Available online.