You are here

Foreign Fighters: Will Revoking Citizenship Mitigate the Threat?

British fighters of the International Freedom Battalion (IFB) in Northeastern Syrian. (Photo: IFB)

As the Islamic State’s “caliphate” has collapsed, flushing out fighters and their families, Western governments are having to contend with the fates of radicalized nationals who may wish to return. Recent high-profile cases of “ISIS widows” have thrown the issue into sharp relief. Britain’s Shamima Begum and the United States’ Hoda Muthana, teenagers who left their countries to join the Islamic State, were denied their wish to return with their newborn children: the United Kingdom stripped Begum of her citizenship, leaving her effectively stateless, while the United States concluded that Muthana was not a citizen based on a technicality. Though the question of so-called foreign fighters has troubled Western countries for some time, the issue of family members and dependents—including young children born abroad who may have uncertain citizenship status—has added further complexity.

Deciding how to handle these fighters—and their dependents—is no easy issue. While many countries have enacted new laws that expand the number of terrorism-related offenses that can be prosecuted (and their geographical scope), experimented with preventative and community-led initiatives, and introduced innovative rehabilitation programs, the blunt desire among many governments and publics is simply to stop these individuals from returning at all.

Though most recent terrorist attacks in Europe and North America have been perpetrated by homegrown terrorists (including white nationalists), rather than those trained abroad, there is a gripping fear that “it only takes one.” But revoking citizenship—a drastic tool that has seen increased use and extended legislation in recent years—has unclear impact and raises deep, philosophical questions about the limits of a state’s responsibility to its own citizens. How countries balance safety and security with their responsibilities to these citizens, especially family members and young children born abroad, could become a watershed moment for the evolution of citizenship and inclusion in modern democracy.

A Profile of Foreign Fighters

An estimated 40,000 radicalized nationals have gone to fight in conflicts in the Middle East—mostly in Iraq and Syria—one-quarter of whom are thought to be women and minors. A majority have purportedly died in combat, but the United Nations Security Council estimated as of February 2019 that as many as 3,000 of these foreign fighters and their dependents remained in Iraq and Syria.

Foreign fighters are nothing new: conflicts from the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War and the 1948 Arab-Israeli War to the Bosnian War of the 1990s attracted ideologically sympathetic volunteers from across the globe. More recently, between 5,000 and 6,000 fighters have left Western countries to fight and train with the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. Of these, nearly 2,000 came from France alone. Flows of fighters have slowed considerably since 2015, as the Islamic State started losing territory and Western states improved efforts to prevent departures. The real question now is one of return—particularly of the thousands of women whose husbands were killed in combat (so-called ISIS widows) and their foreign-born children.

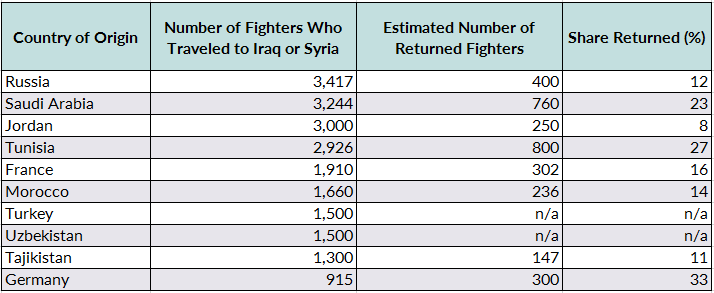

Table 1. Top Ten Nationalities of Foreign Fighters

Source: Richard Barrett, Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees (New York: The Soufan Center, 2017), available online.

Western governments’ main fear is that individuals who have traveled to Iraq and Syria—whether or not they actively participated in armed conflicts—will return armed with new knowledge, networks, and training on how to perpetrate a terrorist offense. However, it is notoriously difficult to assess the risk posed by returnees. First, not all who left for conflict zones planned to fight; in fact, motivations vary widely. And second, their behavior upon return is extremely difficult to predict.

At one end of the spectrum are radicalized Muslims who are already members of extremist networks in their home countries and who indeed traveled abroad to train, consolidate networks, and plan attacks. At the other end are people who see themselves as humanitarian actors who travel to places such as Syria to show solidarity and stand against oppressive regimes. While their original intent may not have been to engage in violent acts, these individuals may have been recruited once abroad. Stretched across the middle of this spectrum are those who may be jihadist sympathizers, motivated by a mix of moral and personal reasons such as thrill-seeking or a desire for a sense of purpose. For example, in Austria, the case of two teenage girls who left to marry ISIS fighters (and were unable to return home and later died) has highlighted the youth and moral ambiguity of ISIS sympathizers.

Whatever their original motivations, individuals joining conflicts in the Middle East are vulnerable to recruitment by extremist groups, and some level of risk exists with all returnees. Even those disillusioned by the brutality of ISIS practices may not have renounced the terrorist ideology. While some may reintegrate into society and disengage from terrorist activities, others may leverage their experience and status to recruit and train new adherents or to plan attacks, including from within prisons, which have become risk areas for radicalization. If the underlying reasons for young people’s disaffection from society and sense of marginalization have not been addressed, they may look back at their time abroad with a false sense of nostalgia and/or lie dormant until a triggering event rekindles their sympathy for terrorist causes. The difficulty is how to determine which subgroup of foreign fighters poses a legitimate threat, and whether (and when) this threat will materialize.

While not all returning foreign fighters pose a threat, the ones who do have perpetrated among the most lethal attacks on European soil. The November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, which killed 130 people and wounded 494—the worst loss of life in France since World War II—were masterminded by a Belgian citizen trained in Syria. A year prior, in 2014, a French citizen who had fought in Syria’s civil war killed four people in a Jewish museum in Brussels. These attacks revealed how terrorists trained and backed by ISIS can deliver exceptional harm.

Citizenship Revocation

For countries struggling with how to address potentially radicalized nationals, there are two main options: allow people to return, which raises questions about the conditions to set and monitoring and rehabilitation programs; or prevent them from returning by revoking their citizenship. The latter raises questions about who can be deprived of citizenship, how to inform them of this decision, and what their alternatives are (including whether they have citizenship of another country). In practice, most countries employ a mix of these two strategies: many have expanded their citizenship revocation powers in recent years, and most have expanded their deterrence and rehabilitation toolkit.

The rationale for passing or expanding citizenship revocation laws is both practical and symbolic. Practical reasons include preventing the re-entry of potential terrorists: Stripping someone fighting abroad of citizenship prevents them from returning home, and therefore—in theory—reduces the security threat they pose and could deter those considering going to conflict zones or perpetuating terrorist offenses. Citizenship revocation can also serve symbolic goals, and thereby allay public anxiety. It sends a strong signal that people who have reneged on their obligations as citizens are no longer entitled to the protection of the state. However, such as a symbolic message can also run into scapegoating, especially if it suggests that the loyalty of Muslims is in question, or that their citizenship is conditional.

While citizenship revocation is currently in the news, it is not new. Some countries have long had laws to strip citizenship from people for behavior that threatens the interests of the state, such as treason or fighting for a foreign government. According to the Global Database on Modes of Loss of Citizenship, more than 130 countries around the world have such legislation on the books, including 19 EU Member States. The fear of a flood of returning fighters has prompted many states to expand their denaturalization legislation. For example, Belgium announced legislation in 2012 to strip those with dual citizenship of their Belgian citizenship if convicted of serious crimes (including terrorism). In 2014 Canada enacted a law to revoke the citizenship of dual citizens convicted of terrorism (though a 2017 amendment later repealed automatic revocation for national security offenses, on the grounds that it treated dual citizens differently than other Canadians). Following the 2015 Paris attacks, the French government proposed a controversial constitutional amendment that would strip citizenship from dual nationals (including French-born citizens) convicted of terrorism, but the bill was ultimately defeated in 2016. The Danish government is the latest to attempt to broaden its legislation, agreeing to new rules in March 2019 (which have not yet been ratified) that would allow citizenship to be summarily revoked for nationals fighting in Iraq or Syria, without giving them their day in court; it would also deny citizenship for children of fighters born abroad.

Because of concerns over statelessness, most countries differentiate between dual/naturalized citizens and citizens by birth. But in some cases, new policies have pushed the bounds of international law. The United Kingdom expanded the scope of its existing laws on revoking citizenship to allow them to be applied even if individuals will be made stateless, provided they have a reasonable chance of acquiring citizenship elsewhere. In 2019, the decision to strip Shamima Begum of her citizenship left her (and her newborn son, who later died) stateless as a possible second citizenship was denied by the Bangladeshi government. Australia’s 2017 citizenship amendment similarly allows the government to revoke citizenship based on having joined a foreign army or having fought for a declared terrorist organization outside of Australia. In December 2018, the government revoked the citizenship of an Australian-born suspected Islamic State terrorist on the grounds that he was eligible for Fijian citizenship from his Fijian father—which was later disputed. It is worth noting, however, that while these governments have pushed up against the limits of what is deemed acceptable under international law, they have stopped short of saying that statelessness is an acceptable outcome; instead, they have hidden behind “technicalities” such as other countries failing to provide a second citizenship.

Finally, several countries have special provisions in their citizenship laws for instances of fraud or misrepresentation—unrelated to national security. In the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, citizenship acquired through naturalization can be stripped with an administrative procedure for those found to have obtained it fraudulently. For example, under the U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act, citizens may be denaturalized if naturalization was procured illegally or through fraud. The U.S. government has had a running operation to detect such instances of fraud for more than a decade, but it gained new steam under the Trump administration. In January 2018 the naturalization of a former Indian national was revoked due to suspected fraud, and the administration was planning to refer 1,600 more cases to the Justice Department for prosecution.

It is not the existence of citizenship revocation laws in and of themselves that poses a problem, but how they are applied—and to whom. Since the right to nationality is considered an international human right, most states limit revocation to cases where individuals possess citizenship of another country (or, in some cases, just have the option of acquiring citizenship of another country) to avoid rendering them stateless. But people with an alternative citizenship are more likely to be naturalized citizens or have foreign-born parents. This effectively creates two classes of citizenship and can send the message that citizenship is only inalienable for some: those who acquired citizenship by birth, and whose parents did too.

Impact: Do Citizenship Revocation Laws Work?

The main objective of such laws is to prevent terrorism and radicalization, either by barring a potential perpetrator from returning from a training camp or fighting abroad or deterring those who may wish to do so in the future. In both regards, evidence is lacking, and in fact some analysts have suggested that these laws may increase the threat, while others argue the opposite.

Preventing Physical Re-entry Does Not Always Prevent Terrorism and Radicalization

Depriving someone of citizenship is not tantamount to preventing them (or their close associates) from perpetrating an attack. First, in a technologically interconnected world, physical presence is no longer necessary to orchestrate criminal acts. Therefore, even if countries could seal their borders against the re-entry of persons whose citizenship had been rescinded, this would not necessarily inoculate them against a threat that is by definition transnational, and could be perpetrated from abroad. Second, individuals determined to re-enter the country will still be able to find ways to do so, including through illegal means. Depriving someone of citizenship could push them further underground, or for those who are not the most serious offenders, prevent them from cooperating with law enforcement.

Focusing on Foreign Fighters May Miss Other, Potentially Higher-Risk Groups

Analysts disagree about how much of a risk returning fighters represent. First, a number of studies argue that most foreign fighters in Iraq and Syria have been recruited and trained to perpetrate attacks in the region rather than in their home countries. Second, evidence (such as fighters returning from Afghanistan and Iraq) suggests that not all foreign fighters return home ready to perpetrate an attack. However, it is difficult to make judgments about risk based on past experiences: terrorism is a “small-number phenomenon,” as a recent report put it—it only takes one returning fighter to cause significant damage.

However, this disproportionate focus on those who have left to fight abroad misses three other groups that are at high risk of radicalization: Marginalized individuals who have connected to terrorist groups abroad, but who have not left; would-be foreign fighters whose departure is foiled by authorities either in their country of origin or transit; and homegrown, domestic terrorists. For example, an individual prevented from traveling to Syria ended up being one of the perpetrators of the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris in January 2015. As the Soufan Center argues, “foiled fighters” pose a particular problem. These individuals have mentally committed themselves to the terrorist cause only to be frustrated by authorities—leaving them with a glorified view of ISIS (without the reality check of life in a war zone) and resentment toward their own government, which may simmer and manifest later in other ways.

Using Citizenship Revocation as a Deterrent May Backfire

One of the arguments for revocation is based on deterrence. Individuals considering fighting abroad may think twice if they know they could lose their citizenship. However, many young people who are vulnerable to recruitment by extremist groups may be unaware of the implications of losing their citizenship. And a further risk is that these laws could make high-target groups, particularly Muslim men, feel victimized and provide fuel to extremist recruiters. According to foreign fighters expert David Malet, recruiters capitalize on a sense of commitment to the transnational Muslim community under threat, and thus persuade them to renege on their obligations as citizens. Another study suggests that perceived injustice against Muslims is one of the key drivers of radicalization in the West, and thus government responses to foreign fighters—especially if perceived of as at the expense of humanitarian concern or other support for what is happening in Syria and Iraq—risks inflaming these sentiments.

Unintended Consequences of Punitive Laws

Targeting all citizens who have gone to Iraq and Syria means that some individuals are caught in the net who may not actually pose a threat. Information about what happens to people who have been deprived of citizenship is not in the public domain. For instance, in response to a question from a member of Parliament, the UK Home Secretary declined to provide information about people who had been deprived of citizenship. According to a number of reports, two men who had been stripped of their British citizenship were killed by American drone attacks. Several prominent lawyers have therefore raised the issue that depriving someone of citizenship releases governments from the obligation to intervene, because external protection by one’s government is one of the main rights of citizenship.

While these laws have significant checks and balanced attached to them to protect individual rights, in practice these are often difficult to fulfil. Authorities may send notice of impending revocation of citizenship to a suspect’s last known domestic address, for instance, but that is unlikely to reach them quickly. And appeals are difficult to organize from overseas.

In addition, questions arise about how to handle foreign-born minor children, who cannot be held accountable for the actions of their parents. At the same time, children as young as 6 have been documented training in terrorist camps, so the threat of indoctrination becomes more serious as time goes on. When Belgian courts overturned the order to repatriate two “ISIS brides” and their six children from Syria, “the Belgian justice ministry said it would still seek to repatriate all children younger than 10 years old from Iraq and Syria.” This arbitrary cutoff could still divide families, however, with older children left behind in camps.

Spillover Effects on Citizenship and Integration

Limiting revocation to dual citizens (as many countries have done) has been perceived by many commentators as stigmatizing immigrants and their descendants, and perpetrating unequal treatment of minorities, particularly Muslims. In the debates on a Canadian bill, several parliamentarians referred to the distasteful implication that citizenship had become a mere privilege for some (namely new members) while remaining a right for native Canadians. This perception of unfairness may, in turn, foster feelings of distrust and disloyalty to one’s country. While evidence on the impact of such laws is not yet available, studies on the anti-terror discourse post-9/11 illustrate the risk that such laws can be divisive. For example, a UK study found that the discourse both entrenched Muslim identity and made people scared to display such an identity publicly.

Anti-terror laws tend to play well with the public at large, as they are designed to send a signal to potential terrorists that certain behavior is incompatible with citizenship. But while this can lead to greater confidence in government among the majority, it can also undermine trust among minority groups, particularly if anti-terrorist laws are perceived as being applied unfairly. This erosion of trust might be especially pronounced in the case of revocation of citizenship, since denationalization has often been a symbol of abuse of government power, recalling horrors such as the Nazis stripping Jews and other minorities of citizenship as a precursor to genocide.

While most terrorist threats are hidden from public view, foreign fighters are unusually visible. Their widespread use of social media, ties to their home country, and prominence in media reports has put them squarely on the public radar. Yet governments have few equally visible responses in their arsenal to assuage public anxiety. Citizenship revocation is one of the only decisive government actions that publics can see and understand, particularly in an area where responses are otherwise cloaked in secrecy. This partly explains the appeal of citizenship revocation even in the face of its many potential costs and unintended consequences.

Alternative Solutions: Prosecution and Reintegration

Alongside new revocation laws, many governments have expanded the offenses that can be prosecuted with the goal of using incarceration to extinguish the risk. Many governments have criminalized going abroad to join groups such as ISIS and prosecuted related offenses widely. For example, a Belgian judge ruled in December 2018 (a ruling since appealed), that two women who wish to return from Syria with their foreign-born children would face five years of prison for having joined a terrorist organization.

But proof of actual terrorist involvement (above and beyond simple presence in a training camp) is often hard to come by given the instability of the region and absence of any law enforcement with which to cooperate. The emergence of encrypted communications technologies such as WhatsApp or Telegraph have made intelligence collection even more difficult. As a result, governments have expanded the number of offenses subject to prosecution and/or made it possible to detain returnees while an investigation is carried out. New offenses on countries’ books include participation in terrorist training camps, traveling to join a terrorist organization abroad, providing or receiving terrorist training, funding a terrorist organization, or even traveling to a particular area of the world. Some of these cast their net especially wide: An EU directive that came into force in March 2017 criminalizes not just traveling to join a terrorist group and receive training, but things such as purchasing train tickets to facilitate the travel, and providing or collecting funds that can be linked to terrorist purposes. In 2019, the Swedish government proposed legislation that would make it a crime to cooperate with a terrorist organization (including recruiting new members or providing resources such as transportation for known members).

Lowering the burden of proof can be problematic, ensnaring some individuals who have not engaged in terrorist behavior. In addition, time spent in prison time risks further radicalization, or set the stage for the radicalization of fellow inmates. Several countries, including Belgium and the Netherlands, are investigating different confinement models (solitary, specialized unit, or mixed); customizing the exit and probation process; training prison staff; and screening, training, and accrediting imams working in prisons. But there is little evidence on whether these prevent recidivism.

The effectiveness of prosecution as a long-term strategy, therefore, is only as good as the broader criminal justice system, including the support that people leaving prison receive to reintegrate into society.

Monitoring, Rehabilitation, and Reintegration

As an alternative to revoking citizenship, countries have sought to impose certain conditions on return—enabling returning fighters and family members to come back subject to fulfilling various conditions. For instance, the United Kingdom is experimenting with temporary exclusion orders, which invalidate a suspected foreign fighter’s passport while allowing him to apply for a one-time permit to travel home. This permit is attached to conditions including reporting to police, participating in deradicalization programs, or attending job-center appointments. The idea here is that known extremists are less likely to perpetrate offenses, especially if kept under close supervision and/or supported to enter mainstream life and dissociate from their former lives. Foreign fighters who disappear are especially risky, as in the case of one of the Backraoui brothers who disappeared after being sent back from Turkey to the Netherlands and was later involved in the Paris and Brussels attacks.

The main challenge here is one of resources: the sheer numbers of people under surveillance in France’s notorious “S File,” for example, are thought to be putting pressure on counter-terrorism monitoring. And in addition to the harm an attack would cause, a further risk is that an attack perpetrated by “known wolves” under state surveillance reveals the limits of these systems and could erode confidence in the ability of government to keep the public safe. Countries with complex governance structures, such as Belgium, have had to clearly delineate who has primary responsibility for monitoring after challenges implementing a multiagency approach.

The ideal goal is rehabilitation—especially if former jihadists can help guide terrorist sympathizers away from that pathway. According to the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, individuals who have successfully returned and reintegrated are “the most effective counternarrative” as they can be perceived to have greater legitimacy than other sources of information, explain the realities of fighting, or convey the message that there is no Muslim duty to fight. In recent years, rehabilitation and reintegration programs have attracted considerable interest for their community-driven, holistic approaches that draw on mental health support, education and employment counseling, and even religious theorizing.

The most famous among these is the Aarhus Model, where Danish authorities have provided 330 returning fighters with psychological counseling and job support. Another innovative approach is the Belgian Vilvoorde Method, which was launched in 2014 and focuses on whole families. But these programs have had mixed success. A deradicalization center in Pontourny, France that utilized civics lessons, therapy, and work support was cancelled early because of extremely high costs, difficulty recruiting participants, and public protests. These programs have also spread to the United States, where a pilot project in the Twin Cities seeks to emulate the Aarhus approach.

While these approaches have had some success, most counterterrorism experts agree that prevention is the best approach. Radicalization in many cases is a symptom of social isolation and marginalization; many of the same tools to support individuals’ reintegration into society could help prevent them disengaging in the first place.

Broader Implications of Debates Surrounding Foreign Fighters

The public debate about foreign fighters has been propelled forward by symbolic arguments about the nature of citizenship and loyalty—and the imperative to assuage public fears—rather than rigorous evidence about the impact of such laws, which remains scarce. In the absence of scientific evidence, discussions center on the possible benefits, such as preventing the return of nationals likely to perpetrate attacks, against the possible costs, such as further alienating already marginalized individuals, stigmatizing Muslims more broadly, and disrupting families and communities, particularly when minor children are part of the equation.

The pressure is high for governments to act, especially at a time when right-wing, populist voices are questioning the benefits of immigration and stoking security and cultural fears. Citizenship revocation and similar laws have a bumper-sticker appeal—offering a decisive solution to a messy problem. This is especially appealing in the field of counterterrorism, where publics rarely hear about successes, only failures. And there is a particularly high cost to a government when an attack is perpetrated by a known threat. Beyond the collateral of the attack itself, there is damage to institutions and public trust in them. This means there is added incentive to err on the side of caution, to the detriment of individual rights (a risk assessment that disproportionately affects minorities).

Debates are also occurring against the backdrop of deeper soul-searching on the modern nature of citizenship—and what governments can reasonably demand of their citizens. Citizenship is supposed to be a nation’s highest currency, but its cachet has been marred by recent trends in acquisition and revocation. Questions of whether citizenship can be “sold” have been floated in the wake of countries offering an expedited path to citizenship to wealthy investors. Another crack in the armor of citizenship is whether new revocation and denaturalization schemes weaken an institution once thought to be permanent and unassailable—and one that provides a level playing field to the most vulnerable.

Ultimately, the political expedience of preventing fighters from returning runs headlong into the complexity of actually carrying it out, and the question of whether these laws provide the best outcome in terms of both national security and integration—or whether the tradeoffs are too steep.

Sources

Barrett, Richard. 2017. Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees. New York: The Soufan Center. Available online.

Briggs, Rachel. 2014. Why Are Westerners Drawn to Fight with IS in Syria and Iraq? And What Can We Do in Response? COMPAS Breakfast Briefing, Oxford, November 7, 2014.

Briggs, Rachel and Tanya Silverman. 2014. Western Foreign Fighters: Innovations in Responding to the Threat. London: Institute for Strategic Dialogue. Available online.

Byman, Daniel and Jeremy Shapiro. 2014. Homeward Bound? Don’t Hype the Threat of Returning Jihadists. Foreign Affairs, November/December 2014. Available online.

Chisti, Muzaffar, Sarah Pierce, and Jessica Bolter. 2018. Even as Congress Remains on Sidelines, the Trump Administration Slows Legal Immigration. Migration Information Source, March 22, 2018. Available online.

Choudhury, Tufyal. 2012. Impact of Counter-Terrorism on Communities: UK Background Report. London: Institute for Strategic Dialogue.

Council of the European Union. 2017. EU Strengthens Rules to Prevent New Form of Terrorism. Press release, March 7, 2017. Available online.

Dawson, Joanna. 2019. Shamima Begum: What Powers Exist to Deal with Returning Foreign Fighters? House of Commons Library, February 20, 2019. Available online.

De Groot, Gerard-René and Maarten Peter Vink. 2014. Best Practices in Involuntary Loss of Nationality in the EU. Center for European Policy Studies Paper in Liberty and Security 73. Available online.

Forcese, Craig. 2014. A Tale of Two Citizenships: Citizenship Revocation for “Traitors and Terrorists.” Queen’s Law Journal 39 (2). Available online.

Global Citizenship Observatory. 2017. Global Database on Modes of Loss of Citizenship, version 1.0. San Domenico di Fiesole: GLOBALCIT, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute. Available online.

Government of Canada. 2015. Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act. May 28, 2015. Available online.

Hegghammer, Thomas. 2014. Oral Evidence Given by Thomas Hegghammer, Director of Terrorism Research at the Norwegian Defense Research Establishment, to the House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee. Session 2013-14, February 11, 2014. Available online.

Malet, David. 2014. The Foreign Fighters Playbook: What the Texas Revolution and the Spanish Civil War Reveal About al Qaeda. Foreign Affairs, April 8, 2014. Available online.

Mythen, Gabe, Sandra Walklate, and Fatima Khan. 2012. “Why Should We Have to Prove We’re Alright?”: Counterterrorism, Risk, and Partial Securities. British Sociological Association 47(2): 383-98.

Parliament of the United Kingdom. 2014. Immigration Act of 2014 c.22. 2013-14 Session. Available online.

Renard, Thomas and Rik Coolsaet, eds. 2018. Returnees: Who Are They, Why Are They (Not) Coming Back and How Should We Deal with Them? Egmont Paper 101, Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations, Brussels, February 2018. Available online.

Reuters. 2019. Belgium Wins Appeal Against Repatriation of Islamic State Families. Reuters, February 27, 2019. Available online.

The Local Sweden. 2019. Sweden Moves to Tighten Anti-Terror Laws: Five Key Things to Know. The Local Sweden, February 28, 2019. Available online.

United Nations Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee. 2018. The Challenge of Returning and Relocating Foreign Terrorist Fighters: Research Perspectives. New York: United Nations Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee. Available online.

Valchars, Gerd. 2014. Austrian Ministers Propose to Denaturalize Austrian Nationals Fighting in Syria. EUDO Citizenship Observatory, May 2014.

Withnall, Adam. 2014. ISIS’s Teenage Austrian Poster Girl Jihadi Brides “Have Changed their Minds and Want to Come Home. The Independent, October 12, 2014. Available online.

Woods, Chris, Alice K. Ross, and Oliver Wright. 2013. British Terror Suspects Quietly Stripped of Citizenship…Then Killed by Drones. The Independent, February 28, 2013. Available online.

World Bulletin. 2014. Belgium Plans to Revoke Foreign Fighters’ Citizenship. World Bulletin, October 10, 2014. Available online.