You are here

Years After Crimea’s Annexation, Integration of Ukraine’s Internally Displaced Population Remains Uneven

Many internally displaced Ukrainians are older individuals, dependent on their government pension for survival. (Photo: Y. Gusyev/UNHCR)

Ukraine, which has one of the largest internally displaced person (IDP) populations in the world, is experiencing the biggest displacement crisis in Europe since the Balkan Wars. Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 after a period of civil unrest and the subsequent onset of armed conflict in eastern Ukraine between Russian-backed separatist forces and the Ukrainian military, civilians fled en masse to unoccupied territories in eastern Ukraine as well as central and western parts of the country. At the peak of military operations in 2015, the Ukrainian government reported some 1.5 million IDPs, with the vast majority from eastern Ukraine and around 50,000 from Crimea. As of July 2019, according to data from Ukraine’s Ministry of Social Policy, there were nearly 1.4 million registered IDPs in a country of 42 million people (excluding the population of what the United Nations refers to as the “temporarily occupied Autonomous Republic of Crimea”)—the 12th largest displaced population in the world.

Box 1. Internally Displaced Persons

According to the UN’s Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, internally displaced persons (IDPs) are “persons who have been forced or obligated to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights, or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized state border.”

Additionally, unregistered IDPs (for whom estimates are difficult to come by) factor into this displacement crisis and may number between 100,000 and 200,000, including some vulnerable categories of children, retired persons, and members of the Roma community. Due to the Ukrainian government’s security concerns and its desire to have better control over money funnelled to the uncontrolled territories, IDPs must register in order to access social benefits, including pensions. Many people living in the conflict area therefore decided to move in order to receive social benefits, which, in practice, means that Ukrainian authorities have unintentionally increased the number of IDPs. On the other hand, those who do not require social benefits often do not register, as the process is arduous and time consuming.

Despite Ukraine’s significantly changing political landscape—including the recent landslide victory of Volodymyr Zelensky in the presidential elections and accelerated reforms in key sectors—Ukrainian authorities are not prioritizing IDP protection. Apart from the economic and humanitarian burden for Ukrainian society (including financial strain from the integration of IDPs in their new communities at a time when Ukraine has lost one-third of its industrial potential and bears the high cost of ongoing military conflict), internal displacement poses challenges related to national identity, social cohesion, and political participation. Despite an initial commitment to grant IDPs full civil and political rights, Ukrainian authorities under former President Petro Poroshenko were quite reluctant to allow IDPs to vote in local elections and limited their access to the pension system.

Moreover, many scholars suggest that the Ukrainian government has failed to adhere to international standards, including the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement and Council of Europe recommendations on IDP enfranchisement, such as easy access to registration and other documentation, unrestricted freedom of movement, access to social and integration services, and access to full political rights. As a result, Ukrainian IDPs are not entitled to vote in local elections and only partially in parliamentary and presidential ones as this right is made conditional upon possessing the permanent residence registration in the new place of residence.

Despite these challenges, IDPs are reluctant to leave Ukraine and move abroad. A growing number would like to stay in their current place of residence, while around one-third plan to return to their original location when conflict ends; in fact, some are already returning. In addition, IDP integration has improved over time, with half of displaced Ukrainians stating they feel integrated into their new destination.

This article explores the experiences of internally displaced Ukrainians, including their socioeconomic situation since the outbreak of the conflict, the Ukrainian government’s policies toward this population, integration and identity issues, and the potential for IDP return or international migration.

An Ongoing Crisis

The November 2013 Euromaidan protests (which broke out after the Ukrainian authorities refused to sign an association agreement with the European Union), and the subsequent downfall of Ukrainian President Victor Yanukovych, were part of a chain of events that preceded Russia’s March 2014 annexation of Crimea. The following month, the annexation ignited an armed uprising against the legitimate authorities by pro-Russian separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk, parts of eastern Ukraine bordering Russia), resulting in intense fighting in April-August 2014.

Despite a ceasefire agreement, prospects for resolving the conflict remain vague, and shellings and hostilities continue sporadically. There is little hope that, at least in the short term, the displaced population will be able to return. Since February 2015, the war theater has been rather constant—around 35 percent of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions remain in the hands of pro-Russian separatists. The so-called Non-Government Controlled Area (NGCA), together with the territories controlled by the Ukrainian government but adjacent to the front line, continue to witness the most displacement. According to United Nations estimates, 5.2 million people bear the brunt of the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine, of whom 3.5 million require humanitarian assistance and protection due to widespread landmine and explosive hazards, escalating psychological trauma, and lack of access to basic services.

As Figure 1 indicates, most displaced persons moved to adjacent regions controlled by the government, others to central Ukraine, and the smallest number to the western regions. Those who moved to adjacent Donetsk and Luhansk often live a mere several dozen kilometres from their previous place of residence. Available research from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) shows that IDPs who moved either to central or western Ukraine perform better in economic terms than those who stayed in a Donbas region, which experienced severe, conflict-induced economic crisis. Moreover, IDPs who moved to the largest cities have had the best living conditions.

Figure 1. Ukraine’s Registered Internally Displaced Person Population, July 2019

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Ukraine: Internally Displaced Persons Registered by Oblast, July 2019, updated July 23, 2019.

Life at the Margins

As Tania Bulakh, Ivanschenko-Stadnik, and Irinia Kuznetsova demonstrate, the majority of IDPs remain in precarious socioeconomic situations several years into the conflict. Despite relative improvement since those first weeks and months after initial displacement, IDPs still have average incomes lower than the national subsistence level, difficulties accessing health care, and poor living conditions such as overcrowded, run-down dwellings or very expensive apartments where rent absorbs most of their income.

However, some research indicates that IDPs’ employment prospects have bettered. In addition, the humanitarian situation in the government-controlled conflict areas has improved due to more regular access to assistance provided by the international community and local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Moreover, over time local authorities and host communities across Ukraine have gradually absorbed the IDP influx and are providing basic public services such as access to primary education for children and basic medical assistance. The displacement crisis has also seen an unprecedented mobilization of civil-society actors in support of the internally displaced.

According to a March 2019 IOM survey, the average income of an IDP household member was almost two times lower than the average income of a non-IDP household member. It is worth mentioning that before conflict erupted, the average incomes in Donbas (the principal region affected by the fighting) were the highest in the country due to the presence of mining and heavy industry.

Apart from economic issues, the biggest issue identified by several IDP needs assessments is a housing shortage and the high cost of rent. Because IDPs spend the majority of their income on housing, they frequently do not possess adequate resources for proper nutrition and health care. For others, the high cost of living has forced them to return to their houses in the occupied territories where, aside from humanitarian concerns, they also risk being caught in the armed conflict.

Finally, age is a critical factor for IDPs’ wellbeing. Many displaced Ukrainians are older and a significant share live off their pensions and are need of health-care assistance. This IDP group is in the most precarious socioeconomic situation, further complicated by the fact that their pension payments are often suspended (as will be discussed later).

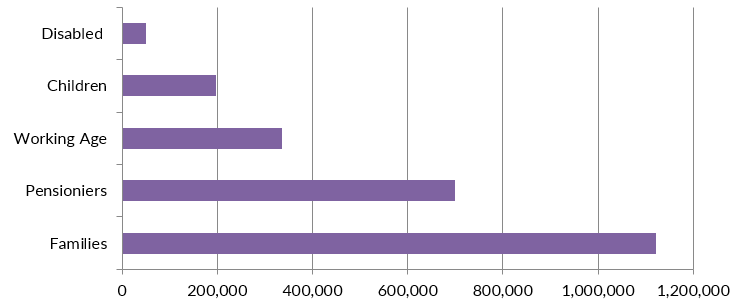

Figure 2. Internally Displaced Persons Registered by the Ukrainian Ministry of Social Policy by Category, Mid-August 2019

Notes: Categories may overlap. Age breakdowns for each category are not possible, as the Ministry of Social Policy aggregates its figures based on the demographic categories.

Source: Author’s tabulation of data from the Ukrainian Ministry of Social Policy of Ukraine.

Since the beginning of the conflict, the international community has played a crucial role in advocating for the protection of the displaced. Nevertheless, international humanitarian funding for Ukraine has been insufficient, mainly due to limited interest from global donors. Some experts claim that attention has waned because displaced populations have not sought to move beyond Ukraine, and thus implicate wider issues associated with international migration. On the other hand, international funding for other mass displacement crises in the world, including conflicts in Syria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), or Somalia is also far less than needed.

Perception and Policies Hinder Integration

Globally, displaced populations face stigmatization and marginalization. In the case of Ukraine, discrimination in the labor market or difficulties renting apartments and hostile contacts with the local population (in particular during the first phase of displacement) have been further complicated by disputes over IDPs’ national identity and loyalty to the Ukrainian state. Particularly right after the eruption of conflict, IDPs have been perceived as co-nationals who may support the enemy (Russia and the separatist forces). There are several reasons for this.

First, this is due to the hybrid nature of Russian aggression toward Ukraine: Beyond military measures, Russia and its proxies have used non-military tactics, including sophisticated propaganda and disinformation campaigns, to elicit support from the population in the Donbas region. This has sparked legitimate fears for the Ukrainian government, including concern over further actions aimed at destabilizing the country’s fragile social cohesion. Second, the different historical and language backgrounds—inhabitants of the Donbas region generally speak Russian, not Ukrainian, and feel more comfortable with Russian culture—and contrasting electoral preferences of the eastern and western parts of Ukraine are significant. Western Ukraine traditionally votes for pro-European parties with rather strong nationalist agendas, while pro-Russian parties are stronger in eastern Ukraine. Of course, the picture is more complex and some distinctions have blurred over time, but these are the main division lines between east and west. Finally, some scholars argue that Ukrainian displacement is creating geopolitical fault-line cities: places with a high potential for the spread of conflict, where contested and remote-controlled narratives come together to polarize the population.

Pension Problems

Due to these reasons, the Ukrainian state has taken a highly securitized approach in shaping policies toward IDPs, including introduction of the arduous and complicated registration procedure to obtain certificates and related social benefits. Moreover, in early 2016 the Ukrainian government decided to suspend payment of social benefits and pensions to IDPs living in the eastern part of the Contact Line (the geographic separation between Russian-supported separatist districts and Ukraine). The government justified the suspension as necessary to verify the list of the persons eligible for social benefits, however neither suspension nor the verification procedure had been stipulated by Ukrainian legislation. In practice, the decision appears to be caused by the government’s fear that IDP benefits could be funneled to the separatists. Ultimately, the measure was disproportionate, and the lack of social benefits caused severe humanitarian problems in 2016-17. For instance, this policy forced the most vulnerable to return to their places of residence in the conflict area, surviving on what they could grow in their gardens and humanitarian food assistance, due to the lack of funding to rent an apartment or buy food.

An additional, unsolved problem is that pensioners who live in the eastern occupied territories must register as IDPs in order to continue receiving pension benefits. The government’s decision contradicts Ukraine’s legal framework and has been acknowledged as unconstitutional by national courts. Several lawsuits against Ukraine at the European Court of Human Rights have been also lodged by IDPs. In practice, the government’s approach has increased the official number of IDPs. It is estimated that around 50 percent of officially registered IDPs in the occupied territories live in their original homes but regularly commute to Ukrainian-controlled territory, where they have registered as IDPs in order to receive their pension.

Other Integration Issues

Displaced persons also suffer from limited electoral rights. Without a fixed place of residence, IDPs have difficulty registering with authorities in their new location. Changing their permanent residence is also administratively burdensome and, in practical terms, almost impossible. For this reason, the vast majority of displaced persons cannot vote in local elections or single-seat elections for Parliament. Several draft bills are pending in Parliament, including a unified electoral code and measures aimed at facilitating IDP voter registration, particularly from territories not under government control. But progress on this front is uncertain: in September 2019, Zelensky vetoed the new electoral code, sending it back to Parliament. However, Zelensky could propose a more comprehensive code that would fully address IDPs’ voting rights.

Despite the policy gaps and difficulties, Ukrainian policy towards IDPs is generally in line with international standards. In the pro-Russian separatist-controlled territories, however, policies are applied unevenly. Apart from very small pensions, paid irregularly, separatists neither provide inhabitants living under their control humanitarian assistance nor facilitate their crossing the Contact Line into Ukraine for work. They may also confiscate property. In comparison, Ukraine provides IDPs legal protection, pensions paid regularly to the majority of registered IDPs, and access to health care, education, and other social services.

Over time, IDPs have become somewhat well integrated in their new places of residence. Initially, host communities were ambivalent about the newcomers, yet this has also improved, but the overall picture is rather nuanced. According to March 2019 survey data from IOM, 50 percent of IDPs reported that they had integrated into their new community, while 36 percent stated that they had only partly integrated. To compare, in previous surveys (conducted since March 2017) the respondents were less likely to choose more moderate answers: that is, more people felt that they had fully integrated (56 percent), and fewer stated they had partly integrated (32 percent). The main issue with this integration self-assessment is the lack of proper housing and protracted separation from family and friends. On the other hand, the level of trust between the local community and the IDP community was reported as high.

International Migration: Not an Option for Ukrainian IDPs

Although Ukrainian displacement is characterized by dynamic internal mobility patterns, these IDPs have not turned to international migration, with only small numbers fleeing Ukraine in the early stages of the conflict in 2014-15. Currently, Ukrainian IDPs are hardly traceable in the general migration flow of Ukrainians to the European Union, who typically arrive on labor permits since channel of international protection are hardly accessible for them (Ukrainian IDPs can obtain a refugee status in EU Member States only in exceptional cases).

Even if Ukrainian IDPs apply for asylum in the European Union, the recognition rate is extremely low. The EU asylum authorities often apply the “internal flight alternative” (IFA) concept, which stipulates that an asylum seeker must prove lack of the possibility of safely relocating and settling in any other part of his or her country of origin before being granted asylum in the European bloc. In 2014, Germany granted refugee or subsidiary protection to 20 of 2,700 Ukrainian applicants; Poland granted 26 out of 2,275 and Italy granted 45 of 2,000. In the following years (except for 2015 when the number of applications in Germany and Italy doubled), both applications and asylum grants have gradually decreased. Poland, however, has granted some IDPs protection in an appeal. Altogether, as of August 2019, 452 Ukrainian citizens were granted humanitarian status in Poland, 380 temporary protection, 98 refugee status, and five the so-called tolerated state status.

Most people fleeing the conflict in Ukraine sought asylum in Russia in 2014-16. However, it is difficult to trace these asylum seekers since Russia ceased registering Ukrainians as asylum seekers, instead considering them labor migrants or granting them quick access to Russian citizenship. Recently, Russia simplified the process for obtaining Russian citizenship for the residents of Donetsk and Luhansk regions, following previous so-called passportization policies implemented in South Ossetia and Abkhazia, the pro-Russian separatist regions in Georgia.

The only method to track the small number of displaced Ukrainians who went to the European Union—estimated to be a few thousand people—is through survey work among Ukrainian migrants. The author’s 2016 qualitative work indicated that IDPs have applied to be labor migrants in Poland, however, this option was available only to working-age Ukrainians with rather high levels of social capital.

As Displaced Population Settles In, Further Reforms Could Improve Integration

More than five years into a conflict that shows no sign of ending, the displaced population, host communities, and the Ukrainian government have come a long way to integrate IDPs into their new places of residence. Still, there remain some important issues that require immediate solution, in particular delinking pension payments from IDP registration. More generally, Ukrainian authorities should think strategically about how they can maintain ties with their citizens in uncontrolled territories and how to promote social cohesion in light of the ongoing conflict with Russia. On an operational level, questions remain whether the IDP framework should still be utilized to refer to this population.

On a political level, the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections that ushered Zelensky and his party into power have blurred (or temporarily frozen) national identity divisions, given that both western and eastern Ukraine voted for the new political movement, whose main leitmotif is to fight against the old political class and old political divisions. In this sense, there is hope that new authorities will be more open to resolve pending issues such as IDP electoral rights. In the long term, however, optimism should remain tempered as it will entail gigantic political and financial will to find a durable solution for the integration of displaced Ukrainians, as well as administrative resources that authorities may not have.

These political, humanitarian, and identity issues are ones that affect Ukraine, not its neighbors. This may be good news for a Europe still shaking off the effects of the 2015-16 refugee crisis, but is not good news for IDPs themselves, as this means less international attention and related humanitarian assistance.

Sources

Bulakh, Tania. 2017. “Strangers Among Ours:” State and Civil Responses to the Phenomenon of Internal Displacement in Ukraine. In Migration and the Ukraine Crisis: A Two-Country Perspective, eds. Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska and Greta Uehling. Bristol, England: E-International Relations. Available online.

Durnyeva, Tetyana. 2019. Недосказане слово (Unfinished Word). Levyj Bereg, August 2, 2019. Available online.

Drbohlav, Dušan and Marta Jaroszewicz, eds. 2016. Ukrainian Migration in Times of Crisis: Force and Labor Mobility. Prague: Charles University. Available online.

Gentile, Michael. 2017. Geopolitical Fault-Line Cities. In Migration and the Ukraine Crisis: A Two-Country Perspective, eds. Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska and Greta Uehling. Bristol, England: E-International Relations. Available online.

Hosaka, Sanshiro. 2019. Hybrid Historical Memories in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine. Europe-Asia Studies 71 (4): 551-78.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019. National Monitoring System Report on the Situation of Internally Displaced Persons. Kyiv, Ukraine: IOM. Available online.

Ivaschenko-Stadnik, Kateryna. 2017. The Social Challenge of Internal Displacement in Ukraine: the Host Community’s Perspective. Geopolitical Fault-Line Cities. In Migration and the Ukraine Crisis: A Two-Country Perspective, eds. Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska and Greta Uehling. Bristol, England: E-International Relations. Available online.

Jaroszewicz, Marta. 2018. Migration from Ukraine to Poland: The Trend Stabilizes. Warsaw: Center for Eastern Studies. Available online.

Krakhmalova, Kateryna. 2018. Internally Displaced Persons in Pursuit for Access to Justice: Ukraine. International Migration August 16, 2018.

Kulyk, Volodymyr. 2016. National Identity in Ukraine: Impact of EuroMaidan and the War. Europe-Asia Studies 68 (4): 588-608.

Kuznetsova, Irina et al. 2018. The Social Consequences of Population Displacement in Ukraine: The Risk of Marginalization and Social Exclusion. Policy Brief, University of Birmingham, Ukrainian Catholic University, Arts & Humanities Research Center, and Partnership for Conflict, Crime & Security Research, April 2018. Available online.

REACH. 2018. Analysis of Humanitarian Trends: Government Controlled Areas of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts. REACH and OCHA, June 2018. Available online.

Sorokin, Oleksiy. 2019. Zelensky Vetoes New Electoral Code, Says It Violates Constitution. Kyiv Post, September 14, 2019. Available online.

State Statistics Service. 2019. Population (By Estimate) as of July 1, 2019. Average Annual Populations January-June 2019. Accessed August 29, 2019. Available online.

Szczepanik, Marta and Ewelina Tylec. 2016. Ukrainian Asylum Seekers and a Polish Immigration Paradox. Forced Migration Review 51. Available online.

UKRINFORM. 2019. Зеленський у Трускавці пообіцяв обговорити з громадскістю захист виборчих прав переселенців (Zelenski in Truskavec Promised to Discuss with Civil Society the Defense of IDPs’ Election Rights). UKRINFORM, August 3, 2019. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019. Key Messages on Internal Displacement. UNHCR, January 2019. Available online.

---. 2019. Ukraine: Internally Displaced Persons Registered by Oblast, July 2019. Updated July 23, 2019.

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). 1998. Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. New York: United Nations. Available online.

---. 2019. Ukraine Situation Report. July 25, 2019. Available online.

United States Agency for International Development (USAID). 2018. Ukraine Social Cohesion and Reconciliation Index (SCORE). USAID, 2018. Available online.