You are here

Haitian Migration through the Americas: A Decade in the Making

A Haitian man hugs his daughter in Peru. (Photo: © UNHCR/Regina de la Portilla)

Editor's Note: This article was updated on May 15, 2023 to correct that Jovenel Moïse was president at the time of his assassination.

The thousands of Haitian migrants who reached the Texas-Mexico border in September were met with stiff opposition from U.S. and Mexican authorities, with many later permitted entry into the United States, others put on expulsion flights to Haiti, and some others returning to southern Mexico. As dramatic and desperate as the scenes at the border were, this migration was years in the making and follows a long path that Haitians have been forging through South and Central America for more than a decade. In many cases, the migrants forcibly returned to Haiti had not been to their native country in years.

Although Haiti has seen significant political crises and natural disasters in 2021—including the July assassination of President Jovenel Moïse and, in August, a 7.2 magnitude earthquake followed days later by Tropical Storm Grace—most Haitians who reached the U.S. border were not fleeing these recent challenges. They are, instead, part of a generation of Haitians who have migrated since their country’s devastating 2010 earthquake, which caused more than 217,000 deaths and left more than 1.5 million homeless. Many of these migrants first attempted to settle in Brazil, then Chile, then went to countries farther north, as local conditions changed and grew increasingly inhospitable. The relaxation of COVID-19-related border restrictions has eased their path northward in 2021, and the election of President Joe Biden may have led to some perceptions that migrants would be permitted to enter the United States. Propelled by these push and pull factors, thousands of other Haitians in South America appear to be poised to undertake the arduous, often dangerous journey to reach the United States.

The journey has resulted in dashed hopes and heartbreak for the approximately 5,400 Haitians who, as of September 30, were returned to their origin country by U.S. officials under a public-health provision preventing access to asylum. For them, the conditions are bleak. The August 2021 earthquake and tropical storm led to the deaths of at least 2,200 people in western Haiti and an estimated 980,000 experiencing food insecurity. In September, the U.S. envoy to Haiti resigned in protest of the expulsions, which he described as “inhumane” and “counterproductive.”

This article chronicles Haitian migration through the hemisphere over the last decade, including the particular challenges that Haitians have faced in the region. Being both predominantly French Creole-speaking and Black, Haitians tend to face obstacles over and above their status as migrants, which has repeatedly resulted in exclusion from certain types of legal protections and frequent targeting for discrimination by state officials and locals alike.

A Portrait of Haitian Regional Migration

Migration from Haiti has been driven by multiple factors, including political and human-rights violations dating back at least to the Duvalier dictatorships of the 20th century. Beyond the vast number of Haitians who died or lost their homes in the 2010 earthquake, tens of thousands more were displaced by Hurricane Matthew in 2016. Insecurity is rampant due to gangs and state-sanctioned violence. Moreover, Haitians also migrate for economic reasons, given that Haiti has the Western hemisphere’s lowest gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Finally, large Haitian diasporas abroad are also a draw for emigrants.

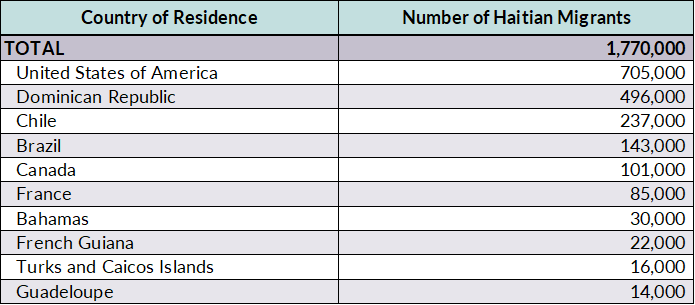

As a result, Haitians have increasingly looked to move to countries including the United States, Chile, and Brazil. Mexico has also become a destination for Haitian migrants, though UN Population Division estimates suggest only around 6,000 were residents as of 2020. While often overlooked, emigration out of Haiti is one of the largest flows in the Western hemisphere (see Table 1).

Table 1. Top Countries of Residence for Haitian Migrants, 2020

Note: French Guiana and Guadeloupe are overseas territories of France but are classified separately for the purposes of UN population estimates.

Sources: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulation of data from the United Nations, “Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination” and “Origin, Table 1: International Migrant Stock at Mid-Year by Sex and by Region, Country or Area of Destination and Origin,” available online; data for Brazil from Santiago Torrado, Rocío Montes, Lorena Arroyo, Carla Jiménez, and Jorge Galindo, “The Silent Exodus of Latin America’s Haitian Population,” El País, August 11, 2021, available online.

South America: Formation of Brazilian and Chilean Diasporas

Following the 2010 earthquake, Haitians migrated to a number of countries, chief among them Brazil, where an estimated 85,000 arrived between 2010 and 2017. At the time, Brazil promised ample construction jobs ahead of the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics. The Brazilian government also offered humanitarian visas to certain Haitians displaced by the earthquake. Additionally, between 2010 and 2015, 48,000 Haitians requested asylum, and significant arrivals continued at least through 2019, when nearly 17,000 Haitians sought protection—more than any other nationality except Venezuelans. As of 2020, Brazil’s Haitian population had grown to an estimated 143,000.

However, after the 2016 job booms from the games wore off, Brazil’s economy stagnated and corruption and political instability grew. Many Haitians already worked longer hours and earned lower wages than Brazilians, and the economic downturn exacerbated their challenges. Those factors, plus persistent racism and growing anti-immigrant sentiment amid the 2018 election of populist President Jair Bolsonaro, drove some Haitians to see Brazil as an increasingly impermanent waystation.

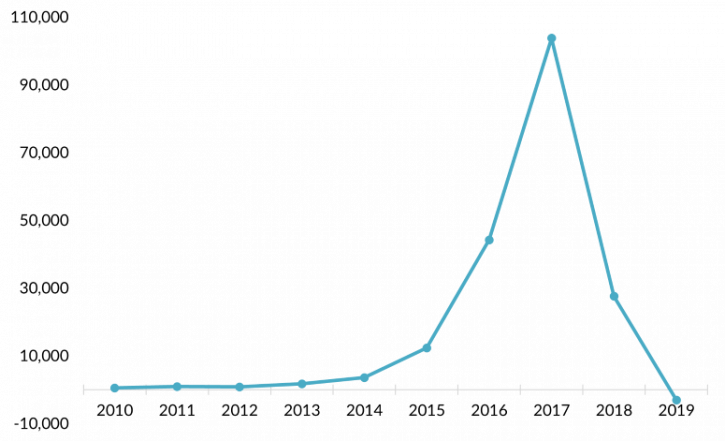

For those who left, Chile became the top destination. In the mid-2010s, Chile was among the region’s most politically and economically stable countries, and until 2018, Haitians could enter without a visa. In 2015, more than 12,000 Haitians arrived in Chile, and this number exceeded 103,000 in 2017.

However, the 2017 election of center-right President Sebastián Piñera led to immigration restrictions. Chile began requiring visas for Haitians in 2018. That year, around 27,000 Haitian entries were recorded. Then, in 2019, more Haitians left Chile than entered (see Figure 1). This is in part explained by the visa requirement, as about 69 percent of all Haitian visa requests were denied over the first two years. For those Haitians who did secure a tourist visa, Chile began to prevent most from acquiring a work permit if they received a job offer.

Figure 1. Annual Change in Haitian-born Population in Chile via Registered Entries, 2010-19

Note: Data reflect the number of Haitians who entered Chile each year and were not registered to have left the country.

Source: Author analysis of Fundación Avina and Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes (SJM), Migración en Chile Anuario 2019: Un Análisis Multisectorial (Santiago, Chile: SJM, 2020), available online.

These policy changes came amid growing anti-Black and anti-immigrant discrimination, along with limited job opportunities. In a 2019 survey of immigrants in Chile, Haitians were the least likely to be employed and reported the most workplace discrimination. About 47 percent of Haitians reported feeling discriminated against while living in Chile. By mid-2020, an estimated 237,000 Haitians lived in Chile, although many have since increasingly opted to leave, this time heading northward.

Figure 2. Map of Common Pathway for Haitian Migrants

Source: MPI artist rendering.

Northward Bound: In Transit through Central America

From Brazil or Chile, Haitians must pass through multiple countries before reaching Mexico. This journey can take anywhere from a few months to a few years, depending on migrants’ resources, time spent in detention centers, stopovers for short-term work, or connections to smugglers. The most physically demanding and dangerous part of the journey is across the Colombia-Panama border, in a region known as the Darién Gap. Migrants must hike across the 150-kilometer (93-mile) jungle, which typically takes between four and 11 days, depending on the season. Migrants frequently run out of food, are robbed, are swept away by rivers during flash floods, or are otherwise injured while crossing.

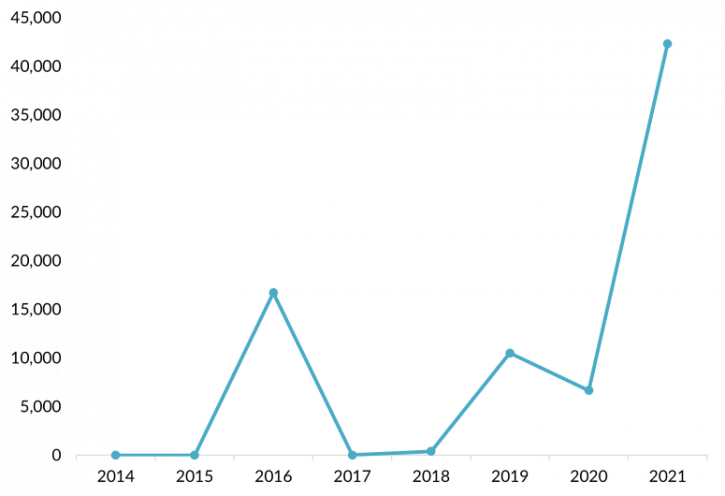

According to Panama’s border service, Haitian migrants did not begin to arrive consistently until 2016, when nearly 17,000 crossed. This was at least in part prompted by Hurricane Matthew, but can also be attributed to changing socioeconomic and political dynamics in Brazil. Since then, Panama has relied on a policy called “controlled flow” (flujo controlado) to receive migrants in camps in southern Panama where they are registered, screened for security purposes, vaccinated, and from where transportation is arranged for them to move northward toward Costa Rica. This lengthy process frequently means that migrants wait for anywhere from several weeks to several months in Panama.

With the significant increase in Haitian—and Cuban—migrants transiting through the region since 2016, Central American countries have struggled to receive them. Nicaragua notably closed its border in late 2015, leaving many Haitians and Cubans stuck for months in Costa Rica. As a result, 2016 was not only the first year that large numbers of Haitians began travelling through Central America, but also the first time that they were trapped in limbo during transit.

Since 2016, the numbers of Haitians transiting through Panama have fluctuated. There were approximately 400 apprehensions in 2018 but more than 10,000 in 2019 (see Figure 3). The drops in Haitian migration after 2016 are explained in part by the United States resuming deportations to Haiti in mid-2016, after a multi-year pause following the 2010 earthquake. While overall figures dropped markedly in 2020 amid the pandemic, the numbers have been unprecedented in 2021, with more than 42,000 apprehensions in the first eight months. Additionally, several thousand children born to Haitians in Chile and Brazil have also been apprehended, increasing this overall figure to around 50,000.

Figure 3. Apprehensions of Haitian Migrants in Panama, 2014-21

Note: Data for 2021 run through August.

Sources: Author analysis of Servicio Nacional de Fronteras (SENAFRONT), “Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: año 2010-2019,” accessed September 23, 2021, available online; SENAFRONT, “Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: año 2020,” accessed September 23, 2021, available online; SENAFRONT, “Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: año 2021,” accessed September 23, 2021, available online.

By all accounts, 2021 is a record year for Haitians transiting through Central America. Colombian officials estimated in July that around 1,500 Haitian migrants crossed the border from Ecuador each day. In August, following diplomatic meetings, Colombia agreed to join Panama and Costa Rica in the controlled flow policy and limit the number of migrants crossing into Panama. As of September, no more than 500 migrants are allowed to cross into Panama per day.

In the meantime, the numbers waiting to cross have increased. Officials in the northern Colombian town of Necoclí estimated in late September that approximately 19,000 migrants were waiting to enter Panama, most of them Haitian. Countries across the Western hemisphere have also established a high-level working group to discuss managing migration, but the large numbers suggest an indefinite bottleneck has developed in and around the Darién Gap.

Mexico

As of this writing, there are no large established Haitian communities in Central America, but the same cannot be said for Mexico. In 2016, an estimated 40,000 Haitians reached the northern Mexican border city of Tijuana. Although fewer Haitians arrived in subsequent years, many of the previous arrivals have remained in the country, either waiting to cross into the United States or settling permanently.

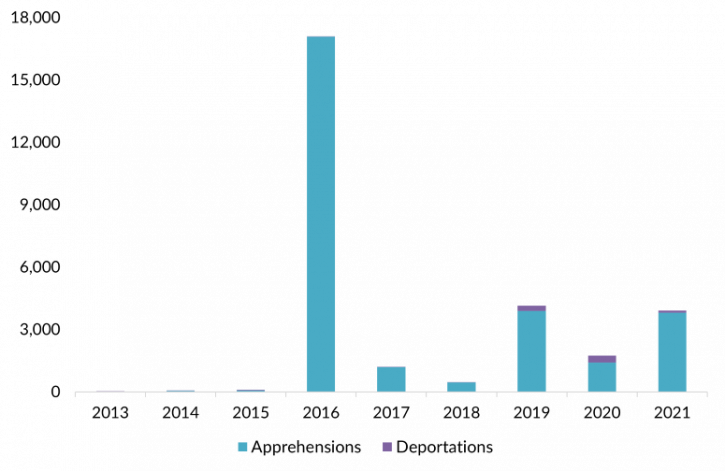

Figure 4. Apprehensions and Deportations of Haitian Migrants in Mexico, 2014-21

Note: Data for 2021 run through July.

Source: Author analysis of Government of Mexico, Boletín estadístico annual, multiple years, available online.

This is in part because many of Mexico’s recent policies have resulted in Haitians spending extended periods of time there. In mid-2019, following pressure from the United States, Mexico stopped issuing exit permits (salvoconductos), which authorities had previously given to apprehended migrants from outside the region whom Mexico had difficulty deporting. These documents allowed migrants to transit through the country toward the United States. With the suspension of exit permits, Mexico has required apprehended Haitians without legal status to stay in its southern region.

In response to the end of exit permits, some Haitians applied for asylum in Mexico, although long wait times and low approval rates dissuaded many. Some were issued one-year humanitarian visas (visas por razones humanitarias), others were declared stateless and issued residency permits, and yet others attempted to find a clandestine way out of southern Mexico. In some cases, legal statuses were provided to Haitian migrants without their consent or full understanding. The result was that Haitian and African migrants in southern Mexico were effectively trapped, either waiting for documents or attempting to leave the region undetected.

Then, in late 2019 and early 2020, Mexico began deporting larger numbers of Haitians (see Figure 4). While Mexico has historically deported Central American migrants after apprehending them, Haitian nationals were treated differently. According to Mexico’s Secretariat of the Interior, between 2013 and 2018, fewer than 1 percent of Haitian migrants who are apprehended in Mexico were deported to their country (118 in total). But in 2019, Mexico deported more than 6 percent of apprehended Haitians (263 overall) and nearly 20 percent in 2020 (341).

Deportations have declined so far in 2021. But Mexican authorities have continued to respond with strict enforcement policies. In August, authorities stopped Haitian and other migrants attempting to transit through Mexico via caravan, and in September authorities apprehended Haitians in the northern border town of Ciudad Acuña (across from Del Rio, Texas) and returned them to Tapachula, in southern Mexico.

Meanwhile, Haitian asylum requests in Mexico have been on the rise. In July and August, Haitians for the first time represented the most common nationality of asylum applicants. This is in part because of the growing numbers of Haitians reaching Mexico from Central and South America, but also due to the bottleneck feature of Mexico’s immigration policy, which forces Haitian migrants to either apply for status to leave southern Mexico, wait indefinitely, or travel covertly. Those who do apply for asylum can wait for months or years before receiving a decision. In the meantime, migrants trapped in southern Mexico lack the ability to work or access social services.

Still, a Haitian diaspora is growing. An estimated 4,000 Haitians live in Tijuana, with several thousand more trapped in Tapachula, and smaller numbers elsewhere.

The United States

The United States hosts the largest Haitian immigrant population, with an estimated 705,000 as of 2020. Many Haitians have been in the United States for years, if not decades. Historically, irregular Haitian migration took place largely by sea, but interdictions of along that route have remained negligible in recent years. Instead, arrivals at land borders have increased consistently. From October 2020 through this August, U.S. Border Patrol made more than 30,000 apprehensions of Haitians, nearly all of them at the U.S.-Mexico border. This marks the most Haitians ever apprehended at the U.S. land border, and the second largest overall since 1992, when authorities intercepted Haitians 38,000 times at sea.

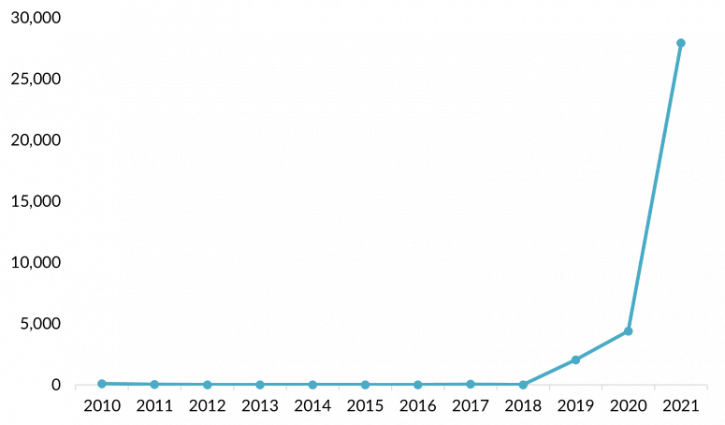

Figure 5. Apprehensions of Haitian Migrants at the U.S.-Mexico Border, FY 2010-21

Note: Data for 2021 run through August.

Sources: Data for fiscal year (FY) 2010 through 2019 from U.S. Border Patrol, “U.S. Border Patrol Nationwide Apprehensions by Citizenship and Sector (FY2007 - FY 2019),” accessed September 29, 2021, available online; data for FY 2020 and 2021 from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, “Nationwide Encounters,” updated September 15, 2021, available online.

This growth is notable in part because Haitian migration to the United States was already increasing prior to Haiti’s mid-2021 crises, reinforcing the evidence that migrants reaching the United States in recent weeks have likely been on the move for years. That said, it is worth noting that the Biden administration has offered Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to Haitians who were in the United States as of July 29, 2021, granting them temporary work authorization and protection from deportation for 18 months. While this action will not affect Haitians recently attempting to cross the border, it did extend protections to 55,000 Haitians already with TPS in the United States and will allow an estimated 100,000 more to apply for new protection. Misinformation about TPS eligibility and about the general availability of legal status in the United States may have been one factor for migrants trying to reach the U.S. border, along with push factors out of South America and the easing of some COVID-19-related travel restrictions.

A Population Quietly on the Move

Dramatic scenes at the U.S.-Mexico border have drawn new attention to the situation of Haitian migrants, but many of these individuals have been quietly on the move for much of the last decade. As they traveled, they have contributed to the growth of diaspora communities in countries including Brazil, Chile, and Mexico.

While on the move, Haitian migrants in Latin America have confronted particular challenges, including intense anti-Black and anti-immigrant sentiment. Being refused work, not being allowed to seek medical treatment or report a crime, and other instances of discrimination often mark the experiences of Haitian migrants in ways not experienced by non-Black migrants. Additionally, Haitian migrants often lack access to translators or interpreters. Non-Spanish and non-Portuguese speaking Haitians are particularly disadvantaged when seeking legal protections, social services, or jobs.

Finally, an increasingly difficult challenge for Haitians relates to the growing number of mixed-nationality families. Children born to Haitian migrants in Brazil, Chile, or elsewhere along their journeys often do not hold Haitian nationality but rather that of the country of their birth. This creates challenges when applying for immigration documents, for families looking to return to Haiti, or simply to prove individuals’ familial relationship. It also presents complications for Haitian families recently returned to Haiti involuntarily by U.S. officials. As of September 23, at least 41 children who do not hold Haitian passports had been expelled to Haiti, forcing the Haitian government to begin discussions with countries such as Brazil on whether and how to return these mixed-nationality families to the countries of the children’s birth.

While data do not show a significant uptick in emigration from Haiti immediately following the recent political and humanitarian crises, these events nonetheless serve as a backdrop that may have played into the decisions of migrants already in Central and South America to seek out new destinations. Still, emigration from Haiti will likely grow in coming months and years, fanning out to countries throughout the Americas where migrants may have families, friends, or work opportunities. As this migration continues, it will be important to distinguish between recent and earlier Haitian waves of migration. Analyses of Haitians’ movement must also to adopt a regional lens that takes into account this decade of hemispheric migration and Haitian migrants’ unique dynamics and challenges.

Sources

Al Jazeera. 2021. Gangs Offer Aid as Haiti Earthquake Death Toll Crosses 2,200. Al Jazeera, August 22, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Mexico Blocks New US-bound Migrant Caravan. Al Jazeera, September 5, 2021. Available online.

Arias, L. 2016. Costa Rica Begins Relocating Migrants Camped Out at Nicaragua Border. Tico Times, September 28, 2016. Available online.

Brazilian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. N.d. Sistema de Refúgio brasileiro: Desafios y perspectivas, Comité Nacional para os Refugiados. Accessed September 21, 2021. Available online.

Bispo, Fábio and Schirlei Alves. 2021. Em Santa Catarina, um terco dos casos de discriminacao no trabalho sao contra haitianos e africanos. Carta Capital, August 5, 2021. Available online.

Charles, Jacqueline. 2018. Haitians Gamble on a Better Life in Chile. But the Odds Aren’t Always in Their Favor. Miami Herald, March 5, 2018. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Sarah Pierce. 2016. United States Abandons its Harder Line on Haitian Migrants in the Face of Latest Disaster. Migration Information Source. October 26, 2016. Available online.

CNN Editorial Research. 2021. Haiti Earthquake Fast Facts. CNN, August 15, 2021. Available online.

Da Silva, Gustavo Junger, Leonardo Cavalcanti, Antônio Tadeu Ribeiro de Oliveira, Marília F. R. de Macêdo. 2020. Refúgio em Números – 5 edição. Brasília: Observatório das Migrações Internacionais. Available online.

Danticant, Edwidge. 2021. The Assassination of Haiti’s President. New Yorker, July 14,2021. Available online.

Drost, Nadja. 2020. When Can We Really Rest? California Sunday Magazine, April 2, 2020. Available online.

EFE. 2021. EE.UU. y México estarán en reunión sobre migrantes en tránsito en Centroamérica. EFE, August 9, 2021. Available online.

Espinoza, Marcia Vera and Leiza Brumat. 2018. Brazil Elections 2018: How Will Bolsonaro’s Victory Affect Migration Policy in Brazil and South America? LSE Latin America and Caribbean blog, October 25, 2018. Available online.

Esquivel, Henry. 2021. Haitian Migrants in Colombia Weigh Journey to U.S. after Deportations. Reuters, September 24, 2021. Available online.

Agence France-Presse. 2021. 19,000 Migrants Amassed in Colombia near Panama Border: Official. Agence France-Presse, September 22, 2021. Available online.

Fouron, Georges E. 2020. Haiti’s Painful Evolution from Promised Land to Migrant-Sending Nation. Migration Information Source, August 19, 2020. Available online.

Fundación Avina and Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes (SJM). 2020. Migración en Chile Anuario 2019: Un Análisis Multisectorial. Santiago, Chile: SJM. Available online.

Government of Mexico. N.d. Boletín estadístico annual. Accessed September 23, 2021. Available online.

Haiti Libre. 2018. Nearly 105,000 Haitians Arrived in Chile in 2017. Haiti Libre, January 15, 2018. Available online.

Harvard Law School International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) and Observatoire Haïtien des crimes contre l’humanité (OHCCH). 2021. Killing with Impunity: State-Sanctioned Massacres in Haiti. Boston: IHCR and OHCCH. Available online.

Hu, Caitlin. 2021. More than 40 Children with Non-Haitian Passports Deported to Haiti, Says International Organization for Migration. CNN, September 23, 2021. Available online.

Infobae. 2021. Unos 1.500 migrantes haitianos tratan de cruzar diariamente la frontera entre Ecuador y Colombia para seguir a Estados Unidos. Infobae, August 9, 2021. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2017. Migration in the Caribbean: Current Trends, Opportunities and Challenges. Working paper, IOM, San Jose, Costa Rica, September 2017. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM) Haiti. 2021. It has been 11 days since the mass repatriations of Haitians from the US started. Over 5,000 migrants have been returned since and more are scheduled to arrive. IOM is on the ground assisting all those returning. @IOMHaiti, Post on Twitter, September 30, 2021. Available online.

Limoges, Barrett 2021. ‘I’m Trapped Here’: Haitian Asylum Seekers Languish in Mexico. Al Jazeera, April 24, 2021. Available online.

Mígracion en Chile. 2021. INE: 14% de los bebés en Chile nacen de madres extranjeras. Mígracion en Chile, 11 January 2021. Available online.

Morley, S. Priya et al. 2021. There Is a Target on Us: The Impact of Anti-Black Racism on African Migrants at Mexico’s Southern Border. New York: Black Alliance for Just Immigration and El Instituto para las Mujeres en la Migración. Available online.

Morse, Julie. 2016. Hurricane Matthew Has Spawned Thousands of New Haitian Refugees. Pacific Standard, October 13, 2016. Available online.

Ornelas, Omar and Lauren Villagran. 2021. Mexican Government Cracks Down on Haitian Migrants in Ciudad Acuña. El Paso Times, September 21, 2021. Available online.

Ramírez, Andrés. 2021. En Julio por primera vez solicitaron más haitianos que hondureños la condición de refugiado en México. La diferencia entre esas nacionalidades fue mínimo: 3942 haitianos vs 3776 hondureños. En el mes de agosto la diferencia creció: 3079 hondureños vs 5613 haitianos. @comar_sg, Post on Twitter by the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance, September 1, 2021. Available online.

Servicio Nacional de Fronteras (SENAFRONT). N.d. Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: Año 2010-2019. Accessed September 23, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: Año 2020. Accessed September 23, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: Año 2021. Accessed September 23, 2021. Available online.

Torrado, Santiago, Rocío Montes, Lorena Arroyo, Carla Jiménez, and Jorge Galindo. 2021. The Silent Exodus of Latin America’s Haitian Population. El País, August 11, 2021. Available online.

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2020. International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin. Accessed September 23, 2021. Available online.

UN News. 2021. Hunger Spikes in Haiti Following Deadly Earthquake. UN News, September 9, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Border Patrol. 2020. U.S. Border Patrol Nationwide Apprehensions by Citizenship and Sector (FY2007 - FY 2019). Updated January 30, 2020. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. 2021. DHS Announces Registration Process for Temporary Protected Status for Haiti. News release, July 30, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). 2021. National Encounters. Updated September 15, 2021. Available online.

Verza, Maria. 2021. Feeling Trapped, Migrants’ Fears Grow in Mexican Border City. Associated Press, September 22, 2021. Available online.

Yates, Caitlyn and Jessica Bolter. Forthcoming. African Migration through the Americas; Drivers, Routes, and Policy Responses. Washington DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Zamorano, Juan. 2021. Panama, Colombia Agree to Limit of 650 Migrants per Day. Associated Press, August 11, 2021. Available online.