You are here

For Overwhelmed Immigration Court System, New ICE Guidelines Could Lead to Dismissal of Many Low-Priority Cases

U.S. immigration officials walk by a courthouse in Seattle. (Photo: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement)

New Biden administration guidelines that ask U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) attorneys to play a more proactive role in exercising prosecutorial discretion could make a serious dent in the record backlog of nearly 1.8 million removal cases pending in immigration courts, including those for asylum. By encouraging the more than 1,250 ICE attorneys to focus on high-priority cases, the new guidance could lead many others to be marked as nonpriority and terminated. Though the administration is advancing the new discretion guidelines as a means of effectively using limited enforcement resources rather than as a backlog-clearing mechanism, the result would be a reduction in the number of court cases pursued by the government. This would speed final resolution of priority cases, bringing faster removal for those found deportable and quicker protection for those who qualify.

The implications are significant not only for people caught up in the immigration courts—including hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers—but could also prove pivotal for the Biden administration’s hopes of streamlining processing of very high numbers of arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border, particularly ahead of an anticipated increase in coming months.

The instructions, spelled out in an April 3 memo by ICE Principal Legal Advisor Kerry Doyle, build on the broad guidance on prosecutorial discretion issued by Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas in September 2021. That earlier guidance established a narrow set of department-wide priorities for immigration enforcement, targeting noncitizens who present a threat to national security or public safety, or who recently crossed the U.S. border without authorization. (These guidelines were temporarily halted by a federal judge but were allowed to proceed in April by the Sixth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. A separate challenge brought by Texas and Louisiana remains pending in a federal court in Texas.)

The Doyle memo, which is the first set of concrete instructions to frontline staff to emerge from the Mayorkas memo, instructs ICE staff to exercise prosecutorial discretion by pursuing high-priority removal cases but offering leniency in low-priority cases. It asks ICE attorneys to decide whether to pursue deportation as early as practical, with a strong preference for seeking termination (also known as dismissal) of low-priority cases, which would remove them completely from court dockets. This could remove the threat of deportation for many noncitizens with deep ties in the United States, including some with old or nonserious criminal convictions.

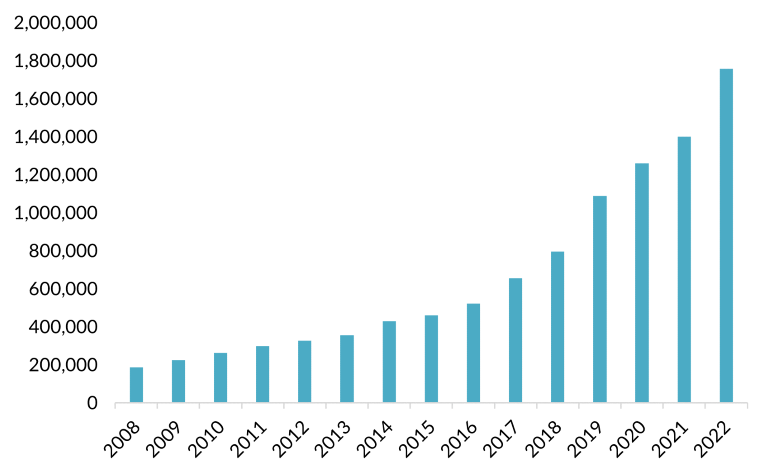

The move is not surprising, given both the administration’s narrative about building a more humane system and the meteoric growth in the number of cases in immigration courts over the last six years. The backlog has more than tripled from about 522,000 cases at the end of fiscal year (FY) 2016 (see Figure 1). This growth is fueled by the courts’ inability to keep pace with incoming cases: In FY 2019, immigration judges took in 270,000 more cases than they completed; last year, the difference was more than 125,000.

Figure 1. Pending Cases in U.S. Immigration Court, FY 2008-22

Note: Data for fiscal year (FY) 2008 through FY 2021 reflect pending cases at the end of the fiscal year. FY 2022 data reflect the backlog through March 2022.

Sources: Data for FY 2008 through FY 2021 are from Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), Pending Cases, New Cases, and Total Completions (2021), available online; data for FY 2022 are from Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), “Immigration Court Backlog Tool,” accessed April 22, 2022, available online.

Backlogs lead migrants to spend years waiting for the outcome of their case. Currently, the average case takes more 855 days to process. This leaves asylum seekers in extended legal purgatory, incentivizes unauthorized border crossings, and delays the removal of criminals, proven national security threats, and other noncitizens ineligible for relief. This article explains the new guidelines for prosecutorial discretion in the Doyle memo and their potential impact in refocusing U.S. immigration enforcement, especially in the courts system.

How ICE Attorneys Can Exercise Prosecutorial Discretion

ICE attorneys, who represent the government as prosecutors in removal cases before immigration courts and in appeals, are among the many government officials who play a role in enforcing immigration law and in exercising prosecutorial discretion, which is the decision whether to pursue a deportation case. In the past, their role in exercising prosecutorial discretion has mainly involved opposing or supporting noncitizens’ requests for leniency, which may take the form of release on bond, delayed court proceedings in maneuvers known as continuances, removal of a case from the court’s calendar, or support of noncitizens’ applications for various forms of relief. At times, ICE attorneys have also petitioned immigration judges for administrative closure of nonpriority cases.

Other arms of the government exercise prosecutorial discretion in different ways. For instance, officials with ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations decide whether to seek custody of a removable noncitizen being held by local law enforcement through issuance of a detainer request. They decide whether to issue a Notice to Appear in immigration court (NTA) and whether to detain noncitizen defendants while their cases are pending. And they determine whether to pursue arrest or deportation for someone issued a final removal order, or whether to temporarily halt a removal order. Immigration judges, meanwhile, decide whether to release detained noncitizens on bond, whether the government has established removability of a defendant, and/or whether the individual is eligible for humanitarian protection or any other relief in the United States. These judges also determine whether to allow continuances in court proceedings, whether to issue a removal order or allow an immigrant to voluntarily depart, and whether to halt immigration court proceedings through administrative closure or termination.

Administrative Closure and Termination

Cases can be removed from immigration court either through administrative closure or termination. Administrative closure, which can occur at any time during a court proceeding, means the case is removed from the court’s active calendar but it remains in the backlog and can be reopened at any time (more than 300,000 cases pending before immigration courts have been administratively closed). Meanwhile, termination of an immigration court proceeding removes the case from the docket altogether, although the government could file new charges. Immigration court proceedings have typically been terminated when the government could not adequately demonstrate that a noncitizen was removable as charged, or to allow them to apply for immigration benefits from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) for which they are eligible, such a family-sponsored green card or for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (for children and youths under age 21 who have been abused, neglected, or abandoned by one or both parents).

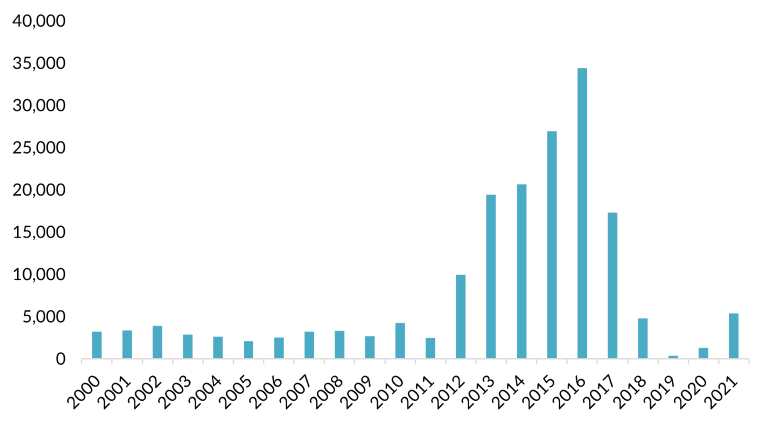

Prior to the new guidelines, ICE attorneys generally have advocated for administrative closure rather than dismissal. Administrative closures were particularly pronounced during the Obama administration, which narrowed enforcement priorities in its later years. During the Bush administration in the early 2000s, fewer than 4,000 cases per year were administratively closed; between FY 2013 and FY 2016 an average of more than 25,000 cases per year were administratively closed. Case closures fell during the Trump administration, even as the number of cases placed before the courts rose (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of Administrative Case Closures in U.S. Immigration Court, FY 2000-21

Source: Justice Department, EOIR, “Inactive but Pending Cases by FY of Administrative Closure,” January 19, 2022. Available online.

Between FY 2000 and FY 2005, the number of cases ending in termination was relatively low (fewer than 10,000 per year, out of more than 150,000 total case completions). Terminations increased to 31,000 in FY 2016, accounting for 15 percent of all case completions (see Figure 3). The use of terminations shrank under President Donald Trump but jumped to nearly 38,000 in FY 2021, accounting for 26 percent of total case decisions, which likely reflects the Biden administration’s interim enforcement guidelines (in place from January through November 2021) suggesting a limited set of circumstances in which ICE attorneys might request dismissals.

Figure 3. Number and Share of Immigration Judge Decisions Ending in Termination, FY 2000-21

Source: TRAC, “Immigration Court Processing Time by Outcome,” accessed April 20, 2022, available online.

Doyle Memo Guidelines

In the past, ICE attorneys generally played a relatively small role in the exercise of prosecutorial discretion, by agreeing (or not) to requests from noncitizens or their lawyers (for those who have representation, which is not guaranteed or required in immigration court) for continuance, administrative closure, or termination of the case. The Doyle memo instructs them to proactively assess whether cases meet new enforcement priorities, as outlined in the September 2021 Mayorkas memo. In addition to refocusing enforcement efforts on national security, public security, and border security, the Doyle memo, tracking the Mayorkas memo, instructs officials to consider a wide range of mitigating or aggravating factors such as a migrant’s criminal history, age, contributions to the United States, length of U.S. residence, and eligibility for humanitarian protection. This totality of circumstances review marks a new approach to prioritizing cases. Under these terms, even a migrant who recently crossed the border without authorization or has a criminal history might not be considered an enforcement priority if there were strong mitigating factors. The Doyle memo stipulates that any case that ICE has already assessed under the Mayorkas guidelines does not need to be reassessed unless new information arises; cases that have not been assessed should receive careful consideration.

The new memo places an emphasis on weeding out low-priority cases from the court docket, setting a higher bar for designating a case as a priority. To do so for cases other than recent border crossers, the new memo dictates ICE attorneys seek review by their chief counsel (or deputy chief counsel, if delegated), but do not need such approval to designate a case a nonpriority.

The memo encourages ICE attorneys to exercise prosecutorial discretion at the “earliest moment practicable to best conserve prosecutorial resources.” This could include instances in which authorities have issued an NTA—which typically marks the formal start of a removal proceeding—but not yet filed it with the court. In these instances, for a case deemed nonpriority, the Doyle memo indicates ICE attorneys should not file the NTA but instead work to cancel it. If a nonpriority case is already in the court system at any stage, the ICE attorney should file a motion to dismiss it.

Importantly, the instructions distinguish between cases in which noncitizen defendants have legal representation—which in the first quarter of 2022 amounted to 53 percent of pending immigration cases—and those who do not. For noncitizens without their own lawyers, ICE attorneys are instructed to first seek a continuance for the person to seek representation, then file a motion to dismiss. For represented noncitizens, ICE attorneys are told to file the motion to dismiss immediately, after informing or consulting the noncitizen’s lawyer, or join a motion to dismiss filed by the lawyer.

ICE attorneys have a range of other—though less preferred—options for exercising prosecutorial discretion, as the memo lays out. They may agree to requests for continuances for other reasons, support administrative closure, or agree to applications for relief. They may also agree to motions to reopen cases so eligible noncitizen defendants can seek relief or legal status, agree to narrow the scope of an individual hearing, or choose not to appeal an immigration judge’s decision in favor of a noncitizen’s claim.

A chief counsel’s decision to assign an ICE attorney to various stages in a particular case is also a matter of prosecutorial discretion under the new guidelines, which could allow for more efficient use of attorneys’ time. The memo says ICE attorneys must be present in only some types of proceedings, but not necessarily in all, including master calendar hearings, in absentia removal hearings (which involve migrants who do not appear in court), or even some hearings on the merits. Allowing ICE attorneys to submit their positions in writing rather than being physically present in a particular hearing may open the possibility for noncitizens’ lawyers to do the same, making court proceedings more efficient.

Finally, the memo instructs ICE’s regional offices to establish procedures for attorneys and community-based organizations to request prosecutorial discretion in a particular case or to ask for review of a priority determination. Such procedures are intended to help hold ICE attorneys accountable for their actions and ensure compliance with the letter and spirit of the guidelines. And the memo encourages local ICE legal officials to establish relationships with community groups and other government agencies to share information about prosecutorial discretion and how to request it.

Important Questions for Implementation

The precise strategies used to implement the Doyle memo will determine its success. Several issues in particular are worth watching.

First, immigration court filings are preponderantly paper-based and records are kept all across the country, likely making it logistically difficult and time-consuming for both ICE attorneys and their superiors to review cases for prioritization. However, the new guidelines may incentivize the government to digitize some existing case files, which would undoubtedly speed up implementation of these guidelines and modernize the archaic system at the same time.

Second, it is yet unclear how and at what stage ICE attorneys will decide which cases to prioritize or deprioritize. Will they evaluate cases as court dates approach, either at a fresh master calendar hearing or ahead of individual hearing dates? Or will they reach back into the pile of pending cases to find those that are ripe for discretion or that are an enforcement priority? Either way, how often will they push for cases to be nonpriority? The agency has been pulled in multiple directions over the last decade, and much depends on ICE attorneys’ levels of enthusiasm.

Third, because only immigration judges can terminate cases, much will depend on how often they agree to ICE attorneys’ motions to do so. Individual judges may take different approaches; the wide variation in asylum grant rates between judges (from an approval rate of 95 percent to a low of 0 percent for the 2016-2021 period) suggests the real impact of the Doyle memo could be very uneven.

Fourth, discretion will presumably differ for different kinds of cases, leading to diverse impacts on noncitizens. Most cases in the court backlog fall into one of three categories: noncitizens with a possible pathway to legal status outside of immigration courts, such as would-be green-card applicants with approved family-sponsorship petitions or unaccompanied children who are likely to be eligible for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status; those with a criminal history; and asylum seekers. For the first group, terminating their case is a straightforward way for them to be able to seek legal status from another government agency, unless they match other enforcement priorities. For the second, people with minor criminal charges will likely be prime candidates for dismissal recommendations, but even those with more serious charges may be eligible for discretion if they have strong mitigating factors. Such migrants would return to their prior status, without fear of immediate removal; those who lack legal status would return to legal limbo but would be relieved of the immediate threat of deportation.

Asylum seekers make up more than one-third of all immigration court cases and could face more difficult choices under the new regime. Those with strong protection claims may want their case to proceed so they can be granted asylum, even if they are not a priority for enforcement. But those who have less clear-cut claims may want their case to be terminated. While termination would end their access to work authorization, it would remove the threat of deportation. This tradeoff may be worth taking because if their case continues in court and is denied, they may not be deported under the Doyle memo guidelines, but a future administration with different enforcement priorities might carry out their removal.

The choices facing all migrants whose cases might be terminated, especially asylum seekers, highlight the importance of having legal representation in immigration court. Lawyers can help noncitizens evaluate their eligibility for humanitarian protection or other relief, assess whether terminating their court proceedings would be beneficial, and either agree to or oppose the motion for dismissal if that would be in their best interest. Therefore, ensuring just outcomes may require connecting noncitizens in removal proceedings to affordable representation.

Potential Impacts

In recent years and particularly under the Trump administration when virtually all unauthorized immigrants were seen as priorities for removal, ICE attorneys were expected to fully prosecute all removal cases. Under the new guidelines, as noted, they will focus on high-priority cases. Therefore, it is likely that the great majority of noncitizens in removal proceedings would no longer face the threat of imminent deportation. The Doyle memo equates the role of ICE attorneys with prosecutors in the nation’s criminal justice system who decide whether evidence supports bringing a charge, and reminds them that immigration enforcement does not consist only of “removals at any cost,” but rather “the government wins when justice is done.”

The new prosecutorial discretion guidelines will directly affect the lives of many noncitizens. They also hold the potential to improve the integrity of the U.S. immigration system writ large. Unauthorized immigrants who have deep ties to U.S. communities and families would seem to be unlikely to face deportation, while migrants who present a real threat to national security and public safety could be removed faster. And because anyone who crossed the border without authorization since November 1, 2020 is a current enforcement priority, the new guidelines could emphasize recent border crossers’ cases, potentially bringing speedier protections for those who are eligible and swifter resolution for those who are not.

High numbers of migrants arriving at the southwest border raise the stakes for the success of the new measures. In March 2022, U.S. authorities recorded more migrant encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border than any month since 2000, and factors such as easing pandemic-related restrictions have raised the prospect of a record number of arrivals over the summer. Such large flows may further compound the pressure on the immigration court system, especially if large numbers of people were to seek asylum.

If adequately resourced and well-implemented, the new prosecutorial discretion practices could relieve some of the strain on this already overburdened system. If judges agree to ICE attorneys’ motions to dismiss many nonpriority cases, the new guidelines could address a legal logjam that has dogged the system for many years, improving the efficiency of court proceedings. Timely, fair court hearings, in turn, can reduce the magnet for irregular migration generated by long waits inside the United States while cases are pending, which smugglers exploit. In concert with new asylum procedures that will allow border claims to be reviewed outside of the immigration court system, the Doyle memo could therefore help alleviate pressure at the border, while also bringing faster protections to asylum seekers with strong cases. Restoring faith in the immigration courts’ ability to quickly adjudicate cases will be imperative for managing border flows and increasing trust in the immigration enforcement system.

Sources

Aleaziz, Hamed. 2022. The Biden Administration Is Now Allowing Prosecutors to Dismiss Certain Deportation Cases. BuzzFeed News, April 4, 2022. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Randy Capps. 2021. Biden Immigration Enforcement Priorities Emphasize a Multi-Dimensional View of Migrants. Migration Information Source, October 28, 2021. Available online.

Department of Justice, Executive Office of Immigration Review. 2019. Statistics Yearbook. Updated August 30, 2019. Available online.

---. 2022. Administratively Closed Cases. Updated January 19, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Current Representation Rates. Updated January 19, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Pending Cases, New Cases, and Total Completions. Updated January 19, 2022. Available online.

Doyle. Kerry E. 2022. Memorandum from Immigration and Customs Enforcement Principal Legal Advisor to All Office of the Principal Legal Advisor Attorneys, Guidance to OPLA Attorneys Regarding the Enforcement of Civil Immigration Laws and the Exercise of Prosecutorial Discretion. April 3, 2022. Available online.

Johnson, Jeh Charles. 2014. Memorandum from Secretary of Homeland Security to Thomas S. Winkowski, Acting Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; R. Gil Kerlikowske, Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection; Leon Rodriguez, Director, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; and Alan D. Bersin, Acting Assistant Secretary for Policy, Policies for the Apprehension, Detention, and Removal of Undocumented Immigrants. November 20, 2014. Available online.

Mayorkas, Alejandro. 2021. Memorandum from Secretary of Homeland Security to Tae D. Johnson, Acting Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; Troy A. Miller, Acting Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection; Ur Jaddou, Director, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; Robert Silvers, Under Secretary, Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans; Katherine Culliton-González, Officer for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties; Lynn Parker Dupree, Chief Privacy Officer, Privacy Office, Guidelines for the Enforcement of Civil Immigration Law. September 30, 2021. Available online.

Miroff, Nick and Maria Sacchetti. 2022. Federal Court Partially Blocks Biden ‘Priority’ System for Immigration Enforcement. March 22, 2022. Washington Post. Available online.

State of Arizona, State of Montana, State of Ohio v. Joseph R. Biden, Jr., Alejandro Mayorkas, Troy Miller, Tae D. Johnson, and Ur Jaddou. 2022. United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, No. 22-3272, on Motion for Stay, United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio at Dayton; No. 3:21-cv-00314—Michael J. Newman, District Judge. April 12, 2022. Available online.

Sullivan, Eileen. 2022. ICE Lawyers Directed to Clear Low-Priority Immigration Cases. The New York Times, April 4, 2022. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2022. Immigration Court Backlog Tool. Updated March 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Immigration Court Processing Time by Outcome. Updated March 2022. Available online.