You are here

Impending USCIS Furloughs Will Contribute to a Historic Drop in U.S. Immigration Levels

An annual July 4 citizenship ceremony at Saratoga National Historical Park, New York. (Photo: National Park Service)

In one of the largest ever furloughs by a single government agency, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) leadership has announced its intent to temporarily lay off 70 percent of the agency’s staff beginning August 30, citing budget issues. The move would dramatically slow the adjudication of a long list of immigration processes, ranging from naturalization to the grant of green cards, nonimmigrant visas, and work permits, among others. Coming on the heels of a series of immigration-related pauses and restrictions imposed by the Trump administration during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 will mark a precipitous—and likely historic—decline in the flow of new arrivals.

The administration’s post-COVID policy decisions—including proclamations to ban the entry of certain categories of foreign nationals and suspension of visa processing—were clearly intended to reduce immigration levels. The USCIS furlough, though perhaps not a planned policy, will effectively achieve the same goal. The agency originally cited a looming $1.2 billion deficit as the reason for a furlough originally anticipated to begin August 3. Agency leaders later said there would be no deficit, yet still intended to continue with the furlough. Under pressure from Senate Democrats, who noted the agency’s changing financial picture, the temporary layoffs were delayed until August 31.

For more than a decade, the number of people who become legal permanent residents (LPRs, also known as green-card holders) has averaged around 1.1 million annually. And in the last five years, the number of temporary (nonimmigrant) visas issued has averaged around 9.7 million yearly, the overwhelming majority of which are issued to tourists and short-term business visitors. These permanent and temporary immigration numbers have shown some signs of reversal during the Trump administration. For example, between fiscal year (FY) 2016, the last full year of the prior administration, and FY 2019, applications for green cards decreased by 17 percent, to the lowest number in half a decade, and the number of people outside of the country applying for temporary visas also fell by 17 percent over the same period.

Yet the potential disruption to the immigration system this year is of a totally different dimension: it could decrease inflows to numbers not seen in decades. The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimates that for each month the USCIS furlough lasts, 75,000 applications for various immigration benefits will not be processed. Presidential proclamations issued on April 22 and June 22, citing the need to protect U.S. workers during pandemic-related job losses, could block a total of 54,000 foreign nationals from entering the United States as immigrants or nonimmigrant workers each month from July through December. And the State Department’s reduced processing has already decreased visa issuance by more than 800,000 visas per month from April through June.

Funds and Furloughs

USCIS is the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) branch that administers benefits and services to immigrants. In 1988, Congress authorized USCIS’s predecessor agency, U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), to establish the Immigration Examinations Fee Account (IEFA), thus allowing it to directly fund its adjudication functions entirely from the application fees that it generates. Thus, 95 percent of USCIS operations are “self-funded” through these fees, unlike most federal agencies, which rely on congressional appropriations. Given that the number of applications for benefits has gone down since the pandemic, agency revenues have also declined. However, USCIS funding troubles predate the public-health crisis.

The budget crisis first came to light in November 2019, when the agency predicted a FY 2020 shortfall of $1.26 billion, which it proposed meeting with a significant fee hike for most applications. Many commentators noted that the shortfall was attributable to a decline in applications, a shift of staff resources from processing to enforcement-driven initiatives, and mismanagement of the agency’s cash reserves. As the COVID-19 lockdown began, USCIS reduced case processing and suspended in-person services beginning March 18. Among the services suspended were interviews required for all applications for green cards and naturalizations.

On May 20, USCIS informed Congress that without an emergency appropriation of $1.2 billion, it would as of August 3 furlough more than 13,000 of its workers—more than 70 percent of the agency’s staff.

Days before the intended furlough, Senate Democrats sent a letter to DHS and USCIS leadership asking them to delay the furlough in light of the agency’s revelation it had funds. According to reporting, the USCIS recorded a revenue increase in the past few weeks and could possibly cover expenses through the end of FY 2020. The House Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship will hold a hearing July 29 to examine the issue. On July 24, USCIS announced it would delay the furloughs until August 30.

Impact of the Possible Furloughs

In addition to adjudicating green cards and naturalizations, USCIS also handles temporary work visas and some humanitarian benefits, such as asylum. Thus, if the furlough goes into effect, it will interrupt nearly all permanent and temporary immigration processing. Among those affected: all those who must apply for authorization to work, such as immigrants eligible for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program—which the U.S. Supreme Court breathed new life into last month.

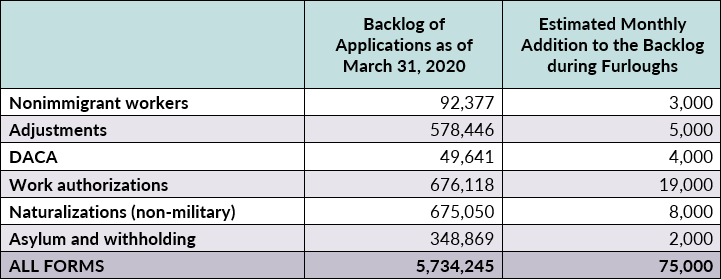

At full staff, MPI estimates that USCIS adjudicates an average of 657,000 cases each month, including 188,000 requests for work authorization, 81,000 naturalization applications, 53,000 requests for a green card, and 56,000 applications for temporary worker visas. Not only would a furlough effectively stop the adjudication of these cases, it would add to an already significant backlog. As of March 31, the backlog stood at more than 5.7 million. Should USCIS furlough 70 percent of its staff, the backlog could grow by nearly 75,000 each month the furlough continues.

Table 1. USCIS Backlog as of March 31, 2020 and Expected Growth During Furlough

Source: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), “Number of Service-wide Forms Fiscal Year To-Date,” multiple years, available online.

Separate from the impact of the potential furloughs, a number of other developments had already resulted in reducing arrivals of the foreign born to the United States this year.

State Department Suspension of Routine Visa Services

On March 18, following the emergency measures announced in response to COVID-19, the State Department suspended routine visa services in most countries; two days later, it expanded the suspension globally. With limited exceptions, foreign nationals abroad were unable to apply for a new or renewed visa to enter the United States. The exceptions included H-2A agricultural workers and H-2B temporary nonagricultural workers, as well as certain medical professionals, their spouses, and children.

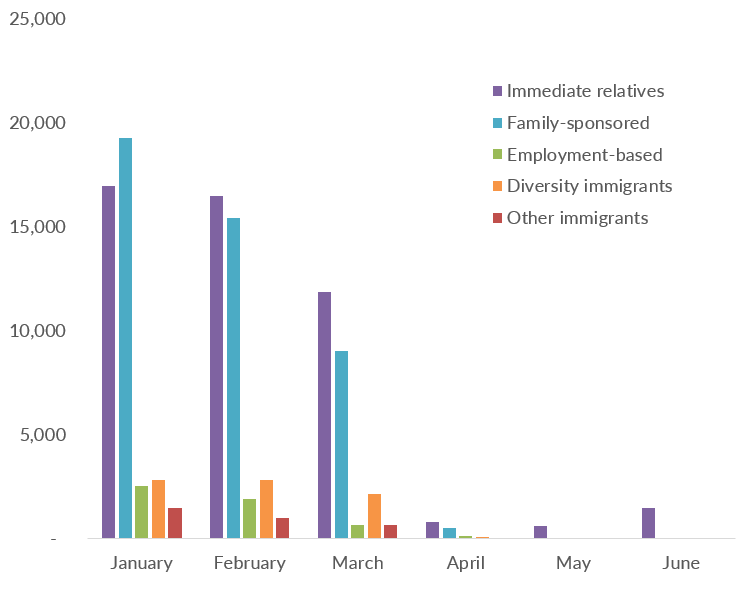

As a result of the suspension, visa issuances fell to historic lows. Overall, immigrant visas dropped by 96 percent—from 43,136 in January to 1,567 in June. Within this overall decline, visas issued to the spouses and children of U.S citizens decreased by 87 percent: from 10,867 in January to 1,435 in June. Visas issued for other relatives of U.S. citizens and LPRs declined even more sharply—a decrease exceeding 99 percent from 25,185 in January to 29 in June. Diversity immigrant visas also fell by more than 99 percent from January to June, with only ten visas granted, a stark reduction from the 5,288 diversity visas granted in June 2019.

Figure 1. Immigrant Visa Issuance, January-June 2020

Source: State Department, “Monthly Immigrant Visa Issuance Statistics,” January-June, 2020, available online.

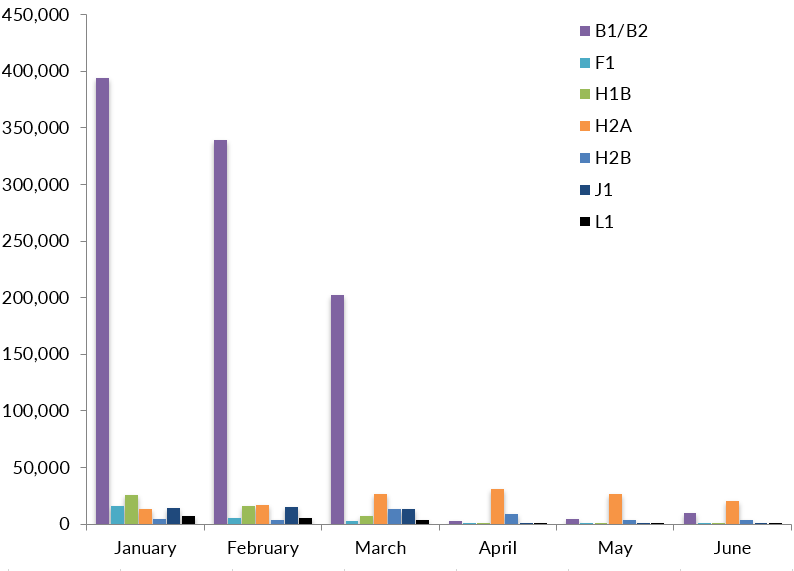

The number of nonimmigrant visas issued by the State Department fell by more than 93 percent, from 670,211 in January to 40,939 in May, and then, perhaps as processing started to resume, increased to 46,435 in June. Within these, issuances of visitor B-1/B-2 visas plummeted from 393,358 in January to 9,523 in June. H-2A and H-2B visa issuance remained largely unchanged from the January levels since they are exempted from the suspension.

Figure 2. Nonimmigrant Visa Issuance, January-June 2020

Source: State Department, “Monthly Nonimmigrant Visa Issuance Statistics,” January-June, 2020, available online.

As the State Department began a phased reopening of services in July, the visa issuance should theoretically increase. But with the continued spread of the coronavirus in the United States, and nonessential travel across the Canadian and Mexican borders still blocked, applications for visas and travel to the United States are unlikely to reach prepandemic levels. Indeed, State Department officials recently testified before the House Foreign Affairs Committee that they did not expect interest in U.S. travel to fully recover until at least 2023. Additionally, U.S. embassies and consulates will only resume services on a post-by-post basis, depending on the improvement of public safety conditions at each location. For areas experiencing ongoing threats from the virus, this will further delay the resumption of routine visa services.

A number of travel bans put into place by the administration in response to COVID-19 will also significantly decrease the number of foreign nationals entering the United States. As of July 26, travel bans are still in place for foreign nationals (other than permanent residents and those falling under a small number of other exemptions) traveling from 31 countries. In addition, the president’s proclamations have placed bans on the entry of certain categories of permanent residents and temporary workers through the end of 2020.

Presidential Proclamation Affecting Permanent Immigration

Following an announcement of his intention to “temporarily suspend immigration into the United States,” President Trump on April 22 signed a proclamation suspending for 60 days the issuance of immigrant visas to persons outside of the United States for most family- and employment-based categories, as well as recipients of diversity visas. On June 22, the president extended the ban through December 31.

Unlike most countries that have imposed post-COVID travel restrictions on health grounds, the president premised the proclamation on protection of U.S. workers against competition from foreign workers at a time of high U.S. unemployment. But the policy will mostly reduce family-based immigration, not employment-based. The proclamation only applies to green-card applicants applying from outside of the country; applicants for employment-based green cards are more likely to already be in the United States working on nonimmigrant temporary visas. While the proclamation reduces employment-based immigration by 15 percent, it reduces family-based immigration by 35 percent.

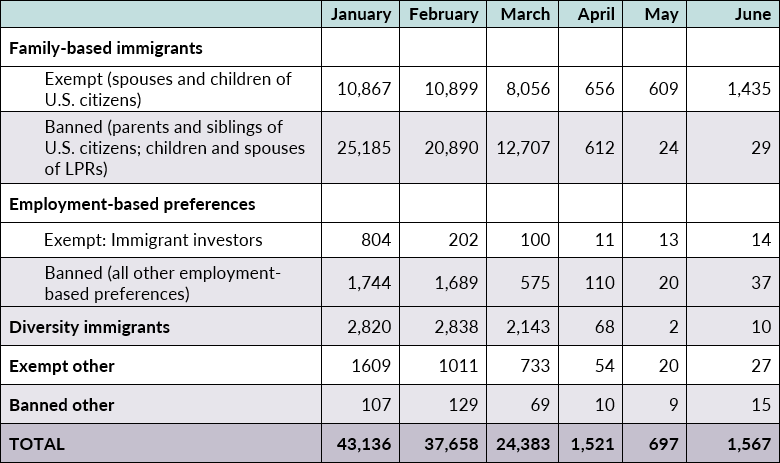

Early data on the proclamation’s impact show a significant drop in visas issued in the categories it targets (see Table 2). The banned categories (in light gray below) decreased by 88 percent between the proclamation’s issuance in April and June, while visa issuance in the exempt categories doubled over the same period. As visa processing begins to restart, the gap between the banned and exempted categories will widen.

Table 2. State Department Immigrant Visa Issuance, January-June 2020

Notes: “Exempt other” includes adoptees and certain special immigrants; “Banned other” includes applicants under the Amerasian Immigration Act and the Amerasian Homecoming Act.

Source: State Department, “Monthly Immigrant Visa Issuance Statistics,” January-June, 2020.

Presidential Proclamation on Nonimmigrants

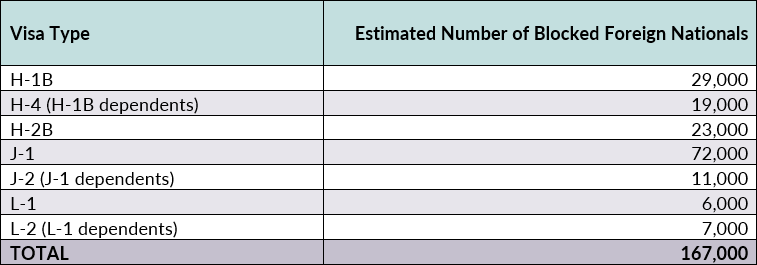

On June 22, 2020, Trump issued a second proclamation which suspended the issuance of certain types of temporary work visas through December 31, as well as extended the April 22 proclamation through the same period. The suspension applied to H-1B visas, for professionals in certain high-skilled occupations; H-2B visas, for temporary nonagricultural workers; certain categories of J visas, for summer work travel program participants and au pairs, among others; L visas, for intracompany transferees; as well as visas issued to dependents of nonimmigrants in these categories (i.e., H-4, L-2, and J-2 visas). The proclamation is limited to foreign nationals who were outside the United States and did not have valid visas in the affected categories on June 24, 2020.

The State Department has since exempted visas for spouses and children of nonimmigrant visa holders already in the United States, some au pairs, and some health-care and public-health professionals and medical researchers with H-1B or L-1 visas.

MPI has estimated that this ban would block 167,000 temporary workers and their family members from coming to the United States.

Table 3. Estimates of Foreign Nationals Blocked July-December 2020 by the June 22 Presidential Proclamation

Sources: State Department, “Monthly Nonimmigrant Visa Issuance Statistics,” multiple years; State Department, “Facts and Figures: 2019 Participants,” accessed July 20, 2020, available online; USCIS, “Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers,” March 5, 2020, available online; USCIS, “H-1B Approvals for Healthcare-Related Occupations,” May 12, 2020, available online.

Implications

The combined effect of the furloughs, the suspension of visa processing, and the president’s proclamations leading to the sharp drop in permanent and temporary immigration will have both short- and long-term consequences.

The furloughs will have the most direct effect on foreign nationals already in the United States. Reduced USCIS staffing will obviously delay—perhaps for long periods—immigrants’ ability to obtain work authorization, gain permanent residence, or finally attain citizenship. Those with temporary (nonimmigrant) visas may not be able to extend or change their lawful stay, thus falling out of status and becoming vulnerable to deportation. Some may not be able to pursue employment for which they have been approved.

The exclusion of categories of immigrants has an adverse effect on U.S. families and U.S. employers. For U.S. citizens and LPRs, it prevents reunification with family members they may have sponsored and waited on for years. U.S. employers, unable to gain access to new temporary employees or frustrated that their sponsored workers cannot join them after being on prolonged waiting lines, may shift their work abroad.

Deep cuts to immigration also have a real impact on the larger economy. With declining fertility and increasing retirement of baby boomers, the U.S. labor force has been experiencing slow growth for some time, contributing to decreased growth in gross domestic product. Immigration, according to many labor economists, is critical to addressing that deceleration.

Finally, sharp decline in immigration this year will have long-term effects on the growth of the foreign-born population. Today’s immigrants—both naturalized citizens and legal permanent residents—sponsor future arrivals. With a contracted base, future immigration will be correspondingly reduced. That will inevitably reduce the foreign-born share of the U.S. population. After trending upwards at a sustained rate since 1970, the U.S. foreign-born population in 2017 and 2018 registered the smallest growth since the onset of the Great Recession in 2008-09. The big dip in immigration in 2020 will not only sharpen that trend but could even mark a historic reversal.

The authors thank Julia Gelatt for her analysis and research assistance.

Sources

Brownlee, Ian and Karin King. 2020. Testimonies of Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, and Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, Overseas Citizen Services, before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, Consular Affairs and the COVID-19 Crisis: Assessing the State Department’s Response to the Pandemic. 116th Cong., 2nd sess., July 21, 2020. Available online.

Cass, Connie. 2013. A Complete Guide to Every Government Shutdown in History. Associated Press, September 30, 2013. Available online.

DeChalus, Camila. 2020. USCIS Postpones Plans to Furlough 13,400 Employees for Now. Roll Call, July 24, 2020. Available online.

Frey, William H. 2019. US Foreign-Born Gains Are Smallest in a Decade, Except in Trump States. Brookings Institution blog post, October 2, 2019. Available online.

Leahy, Patrick. 2020. Leahy Announces that USCIS Is Postponing Furloughs of 13,000 Public Servants, including 1,109 in Vermont. News release, July 24, 2020. Available online.

Leahy, Patrick and Jon Tester. 2020. Letter from U.S. Senators to Chad Wolf, Acting Secretary of DHS, and Joseph Edlow, Deputy Director for Policy, USCIS. July 21, 2020. Available online.

Pierce, Sarah and Doris Meissner. 2020. USCIS Budget Implosion Owes to Far More than the Pandemic. Migration Policy Institute commentary, June 2020. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). N.d. Immigration and Citizenship Data. Accessed July 24, 2020. Available online.

---. N.d. Number of I-485 Applications to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status, multiple quarters. Accessed March 10, 2020. Available online.

U.S. State Department. 2020. Phased Resumption of Routine Visa Services. Last updated July 14, 2020. Available online.

---. N.d. Monthly Immigrant Visa Issuance Statistics. Accessed July 24, 2020. Available online.

---. N.d. Monthly Nonimmigrant Visa Issuance Statistics. Accessed July 24, 2020. Available online.

---. N.d. Worldwide NIV Workload by Visa Category FY 2016. Accessed March 10, 2020. Available online.

---. N.d. Worldwide NIV Workload by Visa Category FY 2019. Accessed March 10, 2020. Available online.