You are here

Lack of Opportunities and Family Pressures Drive Unaccompanied Minor Migration from Albania to Italy

Albanian youth are often expected to contribute to household incomes, leading many to migrate to Italy in search of employment opportunities. (Photo: transition_girl/Flickr)

Geographic proximity and cultural ties have long made Italy an attractive destination for migrants from Albania, as Albanians struggle with limited employment opportunities, corruption, and poverty. One facet of this migration—unaccompanied Albanian children—has received comparatively less attention in Italy than that of minors from the Middle East and Africa, whose arrivals have been more significant in number even as the totals have declined since the 2015-16 European migration and refugee crisis.

Box 1. Children on the Move

Children who migrate are defined by specific terms (children on the move, affected children, separated children, etc.) depending on their individual experiences, travel paths, and specific needs; however, they should be considered children before anything else. Unaccompanied minor (UAM) is the term used to describe children who have been separated from their parents or other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.

Like all children on the move, unaccompanied children have double status as children and migrants, separately but simultaneously, and therefore must be protected twice. Ironically, they are often not protected because they are considered migrants first and children second, automatically minimizing their legal protection, as international standards regarding children are much more elaborated and more widely ratified than those regarding migrants. By being considered migrants, they may be cast as potential lawbreakers who are seeking to abuse the system. By criminalizing their situation, legislation often puts serious restrictions on children’s human rights and restricts their access to services such as education, housing, and health care.

Albanian unaccompanied minors migrate to Italy with the hopes of improving their educational prospects or making money for their families. Despite a 2017 Italian law specifying protections for these youth, they face numerous vulnerabilities. And a 2018 security decree unofficially named for its champion, Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister Matteo Salvini, requires unaccompanied minors to leave reception facilities upon turning 18, rendering many homeless and unable to access programs designed for their welfare. So why, despite all the practical and legal obstacles, do unaccompanied minors from Albania continue to migrate to Italy?

Drawing from research studies conducted by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) office in Tirana, this article explores the emigration of unaccompanied minors from Albania to Italy. It explores the circumstances and motivations for Albanian minors to migrate to Italy, elaborating on the parent-child relationship in the society of origin which influences the migration behavior of minors.

Youth Migration from Albania

During the last three decades, overall emigration from Albania has been quite dynamic. After the collapse of the socialist regime in 1990, thousands of Albanians fled the country. Three subsequent waves of migration (in 1991, 1997, and 1999) prompted hundreds of thousands of Albanians to emigrate to Western Europe.

Box 2. Methodology

The data used in this article were collected through surveys from the family-tracing interview procedure conducted in 2014, and subsequent interviews the following year. Sixty interviews and a follow-up report were conducted by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) mission in Tirana supervised by the IOM in Rome. The author observed the interview protocol and semistructured interviews, viewed as flexible enough to adapt to different contexts and to collect objective and subjective inputs. The interviews were conducted in Albanian and were translated in the author’s presence. The information gained through the author’s observation is used in this article to illustrate completion of the interviews. The interviewees were granted anonymity, in accordance with the sensitive nature of the interviews and in agreement with IOM and the Italian Ministry of Labor.

Upon the approval of visa liberalization between Albania and the European Union (EU) in 2010, migration trends began changing. This act facilitated the regular entry of Albania citizens into EU countries but did not necessarily permit a longer stay. Soon Greece and Italy became the two key destinations for Albanian migrants.

Besides Greece and Italy, Albanian minors also migrate to France, Belgium, and other EU countries. Most of these unaccompanied minors are from rural areas of Albania and emigrate with the intention of staying permanently.

A candidate country to join the European Union, Albania continues to be one of the poorest countries in Europe. With an unemployment rate of 23 percent for young workers (ages 15 to 29) in 2018, job opportunities are difficult to come by. Indeed, the country is experiencing a “minorization of poverty;” not only has there been an increase in the number of young people in poverty, but also an increasing number them are becoming poor because they are young. This poverty leads them to search for ways to survive.

Unaccompanied Minor Numbers and Trends

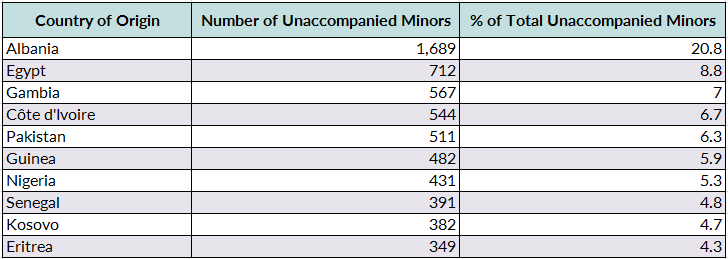

According to the Italian Ministry of Labor and Social Policies, 8,131 unaccompanied minors of all nationalities were in the custody of Italian authorities in April 2019—one-fifth of them (21 percent) from Albania, which was the top country of origin.

Table 1. Top Countries of Origin of Unaccompanied Minors in Italian Custody, April 2019

Source: Italian Ministry of Labor and Social Policies, Report Mensile Minori Stranieri Non Accompagnati (MSNA) in Italia (Rome: Italian Ministry of Labor and Social Policies, 2019), available online.

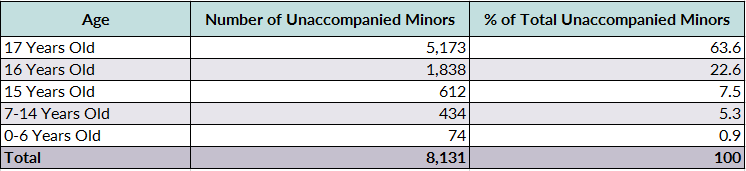

Males represented 93 percent of overall unaccompanied youth, and the vast majority (86 percent) were 16 or 17 years of age (see Table 2).

Table 2. Age Distribution of Unaccompanied Minors in Italian Custody, April 2019

Source: Italian Ministry of Labor and Social Policies, Report Mensile Minori Stranieri Non Accompagnati (MSNA) in Italia.

Why Italy?

The movement of children from Albania to Italy may be explained by a set of interconnected reasons, such as the need to earn family income, migration as a symbol of liberation and being grown up, or the desire to take part in a common behavior. Sometimes, young migrants have difficulty fully grasping and explaining their motivations to emigrate.

The study results show that for Albanian youth, migration to Italy is often considered the most viable option to improve their circumstances and that of their families. For Albanian minors, one of the most important factors in deciding to migrate to Adriatic neighbor Italy is the desire to experience a new way of life. Moreover, declining opportunities for Albanian youth—especially for adolescents transitioning to adulthood—represent the main reason they choose to leave. Many hope to gain residence status in an EU Member State by the time they turn 18.

Continuous exposure to information about life in Italy, often from friends or relatives who have migrated or indirectly via the media (including social media), precedes the decisions of Albanian youth—especially adolescents, to migrate. Usually the decision to move is made after getting positive feedback from a friend or relative who has emigrated. So, economic reasons represent the main pull factor.

Many are also already familiar with the Italian language. Albanian TV programs in Italian play a decisive role in teaching the language, which facilitates a future job search. The existing migrant community networks in Italy are reassuring for minors who, alongside the curiosity and desire for a “new life,” commonly experience anxiety being separated from family and home culture. These networks serve as a guarantor against the culture shock of unfamiliar surroundings and fear of loss of identity.

In addition, the geographic proximity of the two countries—just a ferry ride of several hours or day’s journey via train, bus, or car—plays a role in youths’ decision to migrate, as does a shared history with Italy’s colonization of Albania between the two world wars. Finally, visa liberalization between the two countries eases the challenges of migration and remigration options for Albanian minors.

Family Expectations as a Push Factor

Albanian culture (predominantly among the Roma minorities) dictates the contribution of all family members, so the socioeconomic conditions in the household represent an additional motivation. No matter how radical it may seem, migration is often the most viable solution and is not difficult to imagine for these minors.

Children in these families are raised to believe that it is their duty to contribute to their family’s economic well-being and to spend their free time on work; housework is a shared responsibility. Education is not valued as much as the requirement to contribute to the household. Other groups of parents see the path of school and vocational training offered in Italy as better than the one available in the country of origin. So, the migration of a child becomes a family decision and not only do children discuss their decision to migrate with relatives, but interview results show that parents even provide minors with money to help cover the migration costs. One set of interviewed parents indicated that they “got in debt for the travel fees and took out loans” because they considered their child’s migration the first step in a journey that will hopefully lead to greater opportunities and improvement of the family’s living conditions.

Many have also, from an early age, watched migration occur within the family circle, including that of siblings or parents. In some cases, parents even have “contact with an organization or individual who will smuggle them into Italy and accompany them to a relative’s address or contact someone willing to host them.”

The “Adultization” of Unaccompanied Minors

After the decision is made to migrate—whether their parents are aware or not—Albanian minors undergo a transformation. Some assume they have become adults by taking on a bread-winning role for the family, sending home remittances that diversify household income or repay migration-related debts.

While transitioning rapidly from childhood to adulthood, a process known as “adultization,” many minors also report experiencing “responsibilization,” in which the assumption of new responsibilities causes them to assume social roles unsuitable for their age. This adultization is the result of multifaceted interactions between survival, individualization, independence from the family, the change in models of authority, and contributing to the economy of the family—basically, growing up prematurely.

With the assumption of so much responsibility, minors whose migration journey is not successful may keep their failure secret from their parents, as they may feel they have an obligation to succeed. They sometimes feel shame or fear of returning early, which makes them more vulnerable in an unknown environment.

Protection for Unaccompanied Minors

With all these predictable vulnerabilities, the protection of unaccompanied minors is complicated, starting with the lack of legal acknowledgment of them as a separate category and consequently, lack of political representation. The EU legal framework regarding unaccompanied juvenile migration was developed in 1997 with the adoption of the resolution on reception, stay, and return (or asylum procedure) of minors; yet when it comes to practical developments, individual states are primarily responsible for the protection of children’s human rights and, consequently, the effective realization of rights of children depends on policies enacted by the governments of those states.

As mentioned before, migrants who are minors are treated as adults, which is the consequence of two related reasons. The first one is that laws and instruments protecting children’s rights lack provisions for migrants. Second, there is an absence of a child rights-based perspective in migration-related detention policies. The Italian unaccompanied foreign minors’ protection system is a multilevel system of coexisting institutional bodies that is fragmented. The absence of cohesive national legislation means that several institutions and actors intervene in cases, including the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Labor and Social Policies, the Ministry of Justice, and the Department of Equal Opportunities, leading to fragmentation of the structures and services, which has been much criticized.

In addition, Albanian legislation does not explicitly include provisions on unaccompanied minors. The laws related to children contain no legal provision specifying the type of protection offered to unaccompanied children by the state, making it is possible to refer to several provisions of other legislation that are applicable to them.

One of the active institutions between these two countries is the IOM, which has developed family-tracing initiatives in several migration hotspots that has evolved over time for this specific category of unaccompanied minors, even though it is mainly used in order to return minors to their families.

Family-Tracing Initiatives

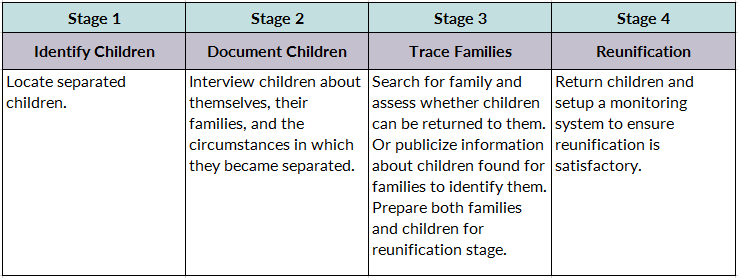

The return of minors to Albania is carried out through family-tracing initiatives. These initiatives, in place since 2008, are used exclusively for unaccompanied child migrants. Family tracing for unaccompanied migrant children who are not requesting asylum seeks to elaborate on the reasons behind migration without a custodian.

IOM engages in family-tracing procedures in numerous countries, such as Belgium, Italy, Norway, and Albania. Relevant information about the child’s life premigration is collected and shared with social workers. Although the main aim officially is to determine the best and most long-lasting solution for the child’s future, the process is, as mentioned, mainly undertaken in order to return the minors to their families. The goal is to trace the families to facilitate minors’ return, and for those whose families cannot be identified or who cannot care for them to set up care and protection facilities in the Italian community where they are resident. As a rule, priority for this family tracing is usually given to younger unaccompanied minors.

Table 3. Family-Tracing Stages

Source: Lucy Bonnerjea, Family Tracing: A Good Practice Guide. Save the Children Development Manual No. 3 (London: Save the Children, 1994).

According to IOM, the family-tracing procedure in Albania involves meeting with minors’ relatives and other community members to determine the socioeconomic context of the family. This is usually carried out through qualitative interviews with the minor’s family or caregivers at their place of residence. Italian authorities initiate this family tracing, typically through the Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) program, for minors wishing to reunite with their families. The IOM Mission in Tirana is the main agency responsible for implementing AVRR-related activities including family tracing, facilitating the family assessment, and travel and communication expenses to return the child.

Family tracing is a long and difficult procedure expected to be completed within 28 days of the official request to undertake a child’s history in hopes of reuniting him or her with the family. Relevant authorities then begin interviews to assess the family’s living conditions. Development of a practical interview system was essential. IOM Rome developed the current interview protocol, based on the input of the Italian Ministry of Labor and Social Policies. At the municipal level in Italy, child protection units (supported by UNICEF) monitor at-risk children and offer protection; identify cases for possible return to families; and coordinate between agencies on the possible return.

Challenges to Effective Family Tracing

According to IOM, a successful family-tracing case is the one in which the child is unlikely to remigrate. Yet not all family-tracing procedures are successful. As the process is initiated with information given by the minor, it is essential to explain that it is not the precondition for return nor a punishment, but a tool for knowing more about them to make an informed decision regarding their fate. Indeed, this information is vital when considering the minor’s age in analyzing his or her answers in the context of deciding whether to initiate family tracing or not. In cases of insufficient or misleading information given by the minor in Italy, it is hard to successfully reunite them with relatives in Albania. It is more time-consuming and expensive to initiate a family-tracing procedure that requires a more extensive assessment because of limited information available.

Another common challenge in collecting information arises when it is unclear whether the parents are truly unaware about their child’s whereabouts or are just pretending not to know. According to the information provided by IOM Tirana staff on family tracing interviews, some of the parents avoided answering the questions due to their fear of punishment or criminal responsibility for abandoning their children. This group of parents deserves careful consideration by IOM, as some parents refuse to accept return of the minor in hopes their child will be permitted to stay in Italy. Parents also hesitate at times to provide details that are sometimes observed from the minor’s point of view as well. According to staff reports, parents have refused, at times, to cooperate and provide information for fear that Italian authorities will return their child. In some cases, for fear of putting the minor in danger, parents refuse to cooperate with interviewers. Other common barriers faced by interviewers include cases where minors came from a divorced family or parents who did not live in Albania.

Overall, according to the family-tracing interview staff, the worst case is when the family cannot be found because the minor refused to or could not provide correct contact information. In such instances, despite the efforts of IOM in Tirana, the case is considered closed by IOM in Rome.

While compared to state initiatives, IOM family tracing confronts many challenges: the time limit of 28 days to close an unaccompanied minor’s case, limited or false information on relatives’ contact details, the family’s hesitation to cooperate because of fear of risking the minor’s position or a complicated family structures. Yet, it is remains unclear whether a successful tracing procedure only benefits the Italian government to send the minors back as soon as possible or if there is a security benefit for youth who otherwise easily become targets of human trafficking and undesirable circumstances in the host country.

Sources

ANSA. 2018. Italy Clamps Down on Immigration as New Security Decree Becomes Law. InfoMigrants, December 20, 2018. Available online.

---. 2019. Migrant Youths Left Homeless Because of Salvini Decree, Aid Organization Warns. InfoMigrants, April 26, 2019. Available online.

Bogdani, Aleksandra. 2018. Albanian Minors Risk Everything to Escape Poverty Trap. Balkan Insight, February 12, 2018. Available online.

Bonnerjea, Lucy. 1994. Family Tracing: A Good Practice Guide. Save the Children Development Manual No. 3. London: Save the Children.

Campani, Giovanna and O. Salimbeni. 2006. La fortezza e iragazzini. La situazione dei minori stranieri soli in Europa. Milan, Italy: Franco Angeli.

Chaloff, Jonathan. 2008. Albania and Italy, Migration Policies and Their Development Relevance: A Survey of Innovative and “Development-Friendly” Practices in Albania and Italy. Working Paper No. 51, Centro Studi di Politica Internazionale, Rome, December 2008. Available online.

Cortés, Rosalia. Children and Women Left Behind in Labor Sending Countries: An Appraisal of Social Risks. Global Report on Migration and Children. New York: UNICEF. Available online.

Demurtas, Pietro, Mattia Vitiello, Marco Accoriniti, Aldo Skoda, and Carola Perillo. 2018. In Search of Protection: Unaccompanied Minors in Italy. New York: Center for Migration Studies of New York. Available online.

European Migration Network (EMN). 2009. Unaccompanied Minors: Quantitative Aspects and Reception, Return and Integration Policies: Analysis of the Italian Case for a Comparative Study at the EU Level. Rome: EMN. Available online.

---. 2014. EMN Study 2014: Policies, Practices, and Data on Unaccompanied Minors in 2014: Italian Case. EMN Fact Sheet, Brussels, 2014. Available online.

Grazhdani, Teuta. 2015. UAM in Migration: Are Care Services Needed? Faculty Journal of the University of Tirana.

Institute of Statistics Albania. 2018. Unemployment Rate, 2018. Accessed July 12, 2019. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM) and Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. 2008. Family Tracing Italy. Accessed July 10, 2015. Available online.

IOM Mission in Tirana. 2015. Reasoning of the Need for Discussion and Action Planning in Relation to the Treatment of Unaccompanied and Separated Children. Roundtable discussion at the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Tirana, Albania. July 7, 2015.

Kearney, Michael. 1986. From Invisible Hand to Visible Feet: Anthropological Studies of Migration and Development. Annual Review of Anthropology 15: 331-61.

Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. 2015. Report Nazionale. Minori Stranieri Non Accompagnati. Rome: Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. Available online.

---. 2019. Report Mensile Minori Stranieri Non Accompagnati (MSNA) in Italia. Rome: Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. Available online.

Ministry of Internal Affairs. 2015. Planning Actions on Treatment of Unaccompanied and Separated Minors. Roundtable discussion at the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Tirana, Albania, July 7, 2015.

Rozzi, Elena. 2017. The New Italian Law on Unaccompanied Minors: A Model for the EU? EU Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy blog post, November 13, 2017. Available online.

Valtolina, Giovanni Giulio. 2014. Unaccompanied Minors in Italy. Challenges and Ways Ahead. Milan: McGraw Hill.

Whitehead, Anne and Iman Hashim. 2005. Children and Migration. Background Paper for Department for International Development Migration Team, Child Migration Research Network, Brighton, United Kingdom, March 2005. Available online.