The Lebanese Crisis and Its Impact on Immigrants and Refugees

Residents in Lebanon — citizens and foreigners — faced a perilous journey to evacuate the war-torn country and reach safe havens in Syria and Cyprus this summer. Before the ceasefire went into effect on August 14, up to 10,000 people arrived at the Syrian border each day, according to a report from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in early August.

Other people arriving at the Syrian border included tourists from the Gulf region who were required to pay to enter Syria, as well as a number of poor Palestinian refugees who were rejected.

About 15,000 American citizens (many of Lebanese origin) were evacuated, as were thousands of Europeans and Australians.

Runways at Beirut's main airport, major bridges, and roads were destroyed by the Israeli military in the fight against Hezbollah that began July 12. In major southern cities like Tyre, infrastructure was so badly damaged that people often were trapped without access to food, water, electricity, or medical care.

At press time, Lebanon’s total losses amount to an estimated $9.4 billion, according to Lebanon’s Higher Relief Commission. In cooperation with the Lebanese government and the United Nations, Sweden hosted an international donor conference on August 31 that brought together about 60 governments and organizations to discuss humanitarian needs and early reconstruction efforts in Lebanon.

The plight of Lebanese citizens has received extensive media coverage around the world. However, another important population has been often left out of the picture: Lebanon's hundreds of thousands of migrant workers and refugees. Their hardships began well before the conflict, yet their stories were rarely told in the media.

Estimates of the number of migrants in Lebanon vary widely since no official records are kept on the migrant population. In the formal economy, it is estimated that foreign workers, mainly from Sri Lanka and Egypt, make up 30 percent of the official workforce, particularly in the domestic and service sectors. Refugees, the majority of whom are Palestinian, and asylum seekers make up about 10 percent of the total Lebanese population of 3.9 million according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

This article investigates the impact of the crisis on several vulnerable groups, including Lebanese citizens in Syria, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and Lebanon's migrant workers and refugees. Finally, it highlights the efforts of the Lebanese diaspora to help fellow nationals.

Lebanese in Syria and the Internally Displaced

By the time Lebanon and Israel signed the ceasefire agreement, the number of Lebanese displaced by the conflict had reached nearly one million. Of those, about 180,000 found refuge in Syria. Another 500,000 IDPs escaped to mountainous regions of Lebanon, where they were sheltered in schools or in homes of host families.

Throughout the crisis, the Syrian government has emphasized its support for Lebanon. Political support was also reflected in its general openness to displaced Lebanese arriving in Syria. In coordination with humanitarian organizations, including UNHCR and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, the Syrian government has worked to provide shelter and relief to Lebanese.

Even in poor rural towns, Syrians accepted refugees into their homes and donated what little food and blankets they owned. Given Syria's limited resources, UNHCR appealed to the international community in early August for help with relief efforts. UNHCR had received nearly $11 million (of nearly $19 million sought) as of August 17.

In response, many countries, including Argentina, Bahrain, and others, sent assistance to Syria in the form of monetary contributions or shipments of supplies. The Turkish government sent nearly 40 truckloads of humanitarian supplies to assist Lebanese in need.

Soon after the ceasefire announcement, many displaced Lebanese chose to make the journey home despite fears that they would have nothing to which to return. Because authorities and agencies are concentrating their relief operations in the hardest-hit towns, people in outlying areas remain in shelters, awaiting assistance to return home.

Nearly 300,000 Lebanese in Syria and Lebanon are still displaced, Lebanon’s Higher Relief Commission reported on August 29. They either have no home return to or fear the return is too dangerous. Their fears are not unfounded: the Higher Relief Commission reported that in the two weeks after the ceasefire, nearly 60 people, including several children, were injured by still-active Israeli explosives in southern Lebanon.

Both the displaced and returning populations suffer from a lack of food, medicine and safe drinking water. Since extreme fuel shortages shut down many hospitals, UNHCR and other aid agencies are coordinating relief operations to send 100 tons of fuel to southern Lebanon.

Migrant Workers

A Brief Overview | ||

|

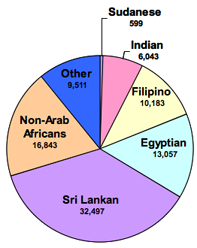

Currently, Lebanon's Central Administration of Statistics (CAS) maintains the only official record of migrants workers in the country: work permits. According to CAS, 90,000 work permits were issued to foreigners in 2002 (see Figure 1).

But, according to some foreign embassy records, the number of their nationals is three times the CAS figure. While Sri Lanka's embassy estimated that around 160,000 of its nationals resided in Lebanon, only 32,497 reportedly held work permits; the rest, who number between 80,000 and 170,000, may hold expired work permits, be unemployed, or be in the country without authorization.

The contract-labor work system in Lebanon isolates migrants from both the local population and from their home country. Employment agencies charge employers in Lebanon high fees to recruit the migrants. As a result, employers withhold their workers' passports to ensure they cannot leave.

Indeed, since the fighting began, IOM has reported numerous cases of employers threatening migrants in order to prevent them from evacuating. Migrant workers without official identity or travel documents wanting to evacuate have had to go to their home government's embassy to get the needed documents or transportation to safety.

However, some foreign governments, like that of Vietnam, do not have embassies in Lebanon. Migrants from those countries have been stranded for long periods without travel documents. Despite the dangers, many migrant workers have chosen not to leave, according to reports from aid workers. Their reasons vary from fear of losing their jobs to going home with no money after years of work to returning to a country where they have no home.

Even governments with embassies in Lebanon have lacked the capacity to help their nationals because they are understaffed and underfunded. Those with some of the largest numbers of migrant workers —Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Ghana — also have the fewest resources to find and evacuate their nationals.

Yet foreign governments have been willing to work together, even when their own resources were limited. For example, India agreed to allow Sri Lankan workers on their ships evacuating Lebanon, and Jordan and Syria offered 4,000 jobs to Sri Lankans escaping Lebanon. Still, neither Syria nor Jordan have clarified what long-term rights these migrants will be accorded.

Most migrant workers in Lebanon have depended heavily on the help of international agencies, such as IOM, UNHCR, and CARITAS, a Catholic relief organization, which coordinate with embassies in order to assist stranded migrants. Since July 20, IOM has evacuated more than 13,000 migrants from Lebanon. Once in Syria, migrants were placed in shelters, where they waited until IOM could arrange their flights home. Following the ceasefire, IOM expected to evacuate at least 1,000 more third-country nationals provided adequate funding was available.

|

According to a representative from IOM, security has been a major concern in its operations. Convoys carrying over 700 people at one time make a dangerous, three-hour passage from Beirut to the border. Additionally, for migrants to return home, IOM had to coordinate with countries such as Saudi Arabia to allow charter flights over areas the organization had never flown over before.

Thus far, foreign governments have supported IOM in its crisis-related efforts. Norway has provided IOM with tents, family kits, blankets, and other materials worth $640,000. The European Commission started a fund of 11 million euros to evacuate nationals from developing countries. This fund makes up more than half of the Commission's total relief budget for Lebanon. Individual European governments have also made significant contributions.

Refugees in Lebanon

Refugees and asylum seekers in Lebanon make up about 10 percent of the country's total population. Palestinians make up the majority of refugees, followed by Kurds, Iraqis, and Sudanese (see Table 1).

Refugees have no official status in Lebanon, as the country has not signed the 1951 UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. UNHCR, which established an office in Beirut in the 1980s, keeps a close watch of refugees and asylum seekers. The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), in existence since 1949, operates under a different mandate than UNHCR, and is responsible solely for Palestinian refugees.

| ||||||||||||||||||

Although refugees came to Lebanon seeking safety from violence and instability in their home countries, the fighting has come to them. Lebanon's refugee camps became home to both refugees and Lebanese civilians in July. Many camps have been bombarded by Israeli attacks, including the country's largest Palestinian camp, where at least two refugees were killed and 15 were injured in August.

Refugees who tried to flee Lebanon generally faced long wait times, or even rejection at the Syria-Lebanon border. Of the hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees, only 1,000 had been allowed into Syria by the end of July. Most of the stranded refugees held valid Lebanese-Palestinian documents but were nevertheless denied by Syrian officials.

UNRWA found that in the three main refugee camps in southern Lebanon, only around 2,900 out of 25,000 refugees left their camps. Attempts to supply water, electricity, and food to refugees still in camps proved difficult as attacks intensified. Nevertheless, UNRWA reported that a total of nearly 29,000 displaced people (both Palestinians and Lebanese) received aid. In addition, the agency opened numerous shelters in schools in both Syria and Lebanon to house Palestinian and Lebanese refugees.

UNHCR reacted to complaints of rejection at the Syrian border by asking Syria to loosen border controls for Palestinian refugees. All governments, UNHCR stated, should follow the principle of nonrejection at their borders during this time of crisis. It asked states not to forcibly return to Lebanon any migrants, including Lebanese citizens, any refugees or stateless persons, or any third-country national. Despite some setbacks, UNHCR expressed overall satisfaction with the Syrian government's cooperation in assisting all refugees coming from Lebanon.

The Lebanese Diaspora

During the 1975-1990 civil war, between 600,000 and 900,000 people fled the country. Since then, internal conflict and invasions from Israel have led to continued emigration. For this reason, Lebanese nationals living abroad number over one million, or about 25 percent of the actual number of people in Lebanon.

However, some estimates put the number of people of Lebanese descent around the world as high as 15 million because of waves of emigration from Lebanon that date back to the late-19th century. Current data show that the United States, Australia, Canada, and Brazil are among the most popular destination countries for Lebanese emigrants and their children.

Past crises in Lebanon have provoked strong reactions from Lebanese communities worldwide, and the current conflict is no exception. From raising millions of dollars to setting up relief centers in Lebanon itself, Lebanese groups in the United States and Canada have provided much-needed aid to their home country.

The Hairi Foundation, a nonprofit organization that promotes training for Lebanese scholars in the United States and Canada, gained media attention when it launched an emergency fund for Lebanon to help victims of the war. In Dearborn, Michigan, the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services held fundraising events to raise $200,000 for medical supplies in Lebanon. A California-based organization, Islamic Relief, raised nearly $1 million by the first week of August for aid to Lebanon and Palestine.

In addition to raising money, organizations are preparing homes and shelters to house fleeing Lebanese refugees. Community organizations have been building their capacity to receive thousands of soon-to-be homeless Lebanese-Canadians. Most of the Lebanese scheduled to arrive left Canada in the past 10 years to return to Lebanon but maintain dual Lebanese-Canadian citizenship.

Since July, protests against Israeli aggression have been a common occurrence in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Before a ceasefire agreement was reach in mid-August, Brazilian government officials had called for an end to the fighting. In an appeal to UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, Brazil's President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva emphasized that the Lebanese-Brazilian connection makes Brazil feel "directly affected by the violence against civilians in the region."

Conclusion

Many migrants and refugees in Lebanon have been trapped between a host country where they face danger and a home country to which they are hesitant or may not be able to return.

For Lebanese, the return home is uncertain and dangerous, as the ceasefire agreement remains shaky. In the coming months, IOM plans to assist displaced Lebanese families as well as migrants, a number of which still want to return home. With its funds already running low, however, IOM will require an additional $26 million for future operations.

The immediacy of the conflict in Lebanon makes it difficult to predict its lasting effects on vulnerable populations. Whatever the outcome, the impact of Lebanon's crisis on migrants and refugees will have implications for the entire Middle East.

Sources

Alsalem, Reem (2006). "Lebanese who cannot return home fear being forgotten." UNHCR, August 28.

Agence France Presse (2006). "Factfile on Lebanon." July 15.

———. "Evacuation of migrant workers from Lebanon resumes." August 7.

———. "Israeli strike on Palestinian refugee camp kills two, wounds 15." August 9.

BBC Worldwide (2006). "Brazil 'directly affected' by situation in Lebanon." August 5.

BBC (2006). "Turkey Sends Aid to Refugees in Syria, Lebanon." August 14.

CARITAS Lebanon (2006). "Situation in August 10, 2006."

Calandruccio, Giuseppe (2005). "A Review of Recent Research on Human Trafficking in the Middle East." International Migration, Volume 43, Issue 1-2.

CIA World Factbook (2006). "Lebanon." Available online.

Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty (2005). Global Migrant Origin Database. Available online.

Embassy of Lebanon, Washington, DC (2006), Prime Minister Fouad Siniora's address to the IOC Meeting, August 3.

European Commission (2006). "11 million to evacuate citizens of developing countries from Lebanon." July 26.

Hamilton, G. and Patrick, K. (2006). "Why 40,000 Canadians are in Lebanon: Migrants from Civil War Often Go back Every Summer." National Post, Toronto Edition. July 21.

Higher Relief Commission (2006). "Daily Situation Report No. 34." August 29. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (2005). World Migration: Costs and Benefits of International Migration, 2005.""

International Organization for Migration (2006). "First Convoy of Sri Lankans Leave Lebanon", July 20.

———. "More Stranded Migrants Evacuated." July 25.

———. "IOM Steps Up Evacuation of Stranded Migrants from Lebanon." July 26.

———. "IOM Accelerates Evacuation of Foreign National." August 7.

———. "IOM Base in Southern Lebanon to Provide Assistance to Internally Displaced and Stranded Migrants." August 1.

———. "IOM and UNHCR Help Lebanese Return from Syria." August 18.

Jureidini, Ray and Moukarbel, Nayla (2004). "Female Sri Lankan domestic workers in Lebanon: A case of 'contract slavery'?" Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies, Vol. 30, Issue 4.

Lennon, Stephen (2006). Email correspondence, August 2.

Malaysian National News Agency (2006). "Jobs for Fleeing Lankan Migrant Workers From Lebanon." July 23.

Mahony, Honor (2006). "Solana welcomes Swedish proposal for Lebanon donor conference." Euobserver.com, August 10.

Omelaniuk, Irena (2006). Email correspondence, August 7.

Shadid, Anthony (2006). "Bombing Obliterates Last Route out of Tyre." Washington Post, August 8.

Shehadi, Nadim (2006). Email correspondence, August 11.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2004). Statistical Yearbook. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2006). "Lebanon: Arrivals in Syria mostly returning Syrians; UNHCR monitoring Iraqis and Sudanese."

———. "UNHCR Considerations on the Protection Needs of Persons Displaced Due to the Conflict in Lebanon and on Potential Responses." August 3.

———. "Syrian villagers open their doors to mass arrival of Lebanese refugees." August 8.

———. "UNHCR distributes relief items for displaced in Lebanon's mountain regions." July 27.

———. "Flash update No. 3." August 17. Available online.

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2006). "Palestinians still stranded on Syrian-Lebanese border." July 28, available online at irinnews.org.

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. "Lebanon Refugee Camp Profiles." Available online.

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (2006). "Syria Revisited."

———. "The Situation of Palestine Refugees in South Lebanon." August 15.