You are here

Living in Limbo: Displaced Ukrainians in Poland

A collage of Ukrainians in Poland. (Photos: Tamar Jacoby)

Many nations are skeptical of refugees, if not downright hostile, and in the past Poland was no exception. A survey in August 2021, just six months before Russia invaded Ukraine, found a majority of Poles opposed to admitting migrants of any kind, including refugees, and nearly half agreed that Poland should build a wall along its border with Belarus, where thousands of Iraqis, Syrians, and other migrants were stranded.

But the mood changed dramatically when Ukrainians began arriving in February 2022. The numbers were overwhelming. By March 7, after just ten days of war, more than 1 million Ukrainians had crossed the border into Poland. By March 18, the total was 2 million; by late April, nearly 3 million. Some of these new arrivals continued on to third countries; others returned to Ukraine. As of this writing, there had been 6.8 million border crossings from Ukraine to Poland, far more than to any other country. Yet instead of averting their eyes or renewing calls for a wall, Poles rushed to welcome the newcomers.

Poles’ feelings for their neighbors were on display in every city. Blue and yellow Ukrainian flags hung in the streets, public signs welcomed the exiles; volunteers in dayglow vests helped staff reception points in train stations, bus depots, airports, and shopping malls. Even local shopkeepers were stepping up. One grocery store posted a sign on a shopping cart near the exit: “Please take an item from your bag to help feed our Ukrainian guests.” A visitor rarely met a Pole who was not doing something to help, often by donating money or making runs to the border with coats, blankets, hot food, or medical supplies. Tens of thousands of homeowners applied to a government program that paid a small subsidy—40 zloty, the equivalent of U.S. $8, per day—to those who housed a Ukrainian family. According to one study, more than two-thirds of Poles helped in some way.

Some analysts attribute the Poles’ change of heart to a cultural or ethnic similarity with Ukrainians and longstanding ties between the two countries. But when asked why they did what they did, many Poles talked about a sense of solidarity with opponents of their longtime adversary, Russia, perceived by many to have posed a threat since medieval times. “The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” one Polish man explained to the author. “Ukraine is fighting for Poland as much as for Ukraine, fending off both our countries’ age-old enemy, Russia.”

Eight months later, an estimated 3.2 million Ukrainians remain in Poland, including 1.3 million labor migrants who were present before the Russian invasion, according to the Union of Polish Metropolises. Altogether, Ukrainians account for nearly 9 percent of Poland’s population.

The war is raging as fiercely as ever, but the forced migration crisis no longer seems as urgent. The flow across the border has slowed to a trickle. Many who arrived last spring are returning to Ukraine, and those remaining in Poland are less visible. Importantly, there has been no public backlash against the new arrivals, a result perhaps of Poland’s distinctive approach, which relies more on civil society than government subsidies. The newcomers’ needs have changed; they are now less concerned about blankets and hot soup than jobs and schooling. But there are many challenges ahead and momentous questions for both Poles and Ukrainians.

This article describes the situation, based on interviews with 45 Ukrainians in Poland conducted for the author’s book Displaced: The Ukrainian Refugee Experience.

Who Are the Displaced?

In fact, no one knows exactly how many Ukrainians have settled in Polish cities. Different ways of counting produce dramatically different results. Looking at the number registering to receive government services, for example, would suggest some 52,000 displaced Ukrainians in the metropolitan area of Krakow, Poland’s second largest city with an overall population of nearly 1 million.

But another approach, aggregating cellphone information of users who appear to be Ukrainian, generates much larger totals, in part because it includes those who arrived before the invasion. This method suggests there may be 180,000 Ukrainians living in Krakow. Some local officials believe as many as 130,000 of them may be people displaced by the war.

Just who they are is even harder to ascertain; there are no official data and only a few independent surveys. One study conducted in early summer by a group of Krakow-based university researchers at the Multiculturalism and Migration Observatory (MMO) suggests that 95 percent of Ukrainian newcomers are women, most are between ages 31 and 45, and 78 percent have children. Only a tiny share are men, since, with a few exceptions for caretakers and large families, fighting-age men have not been allowed to leave Ukraine.

The Refugee Experience

A series of interviews with displaced Ukrainians conducted by the author in Krakow in early spring painted a fuller picture. Every painful story was unique. But together, they added up to a collective portrait of the Ukrainian refugee experience.

Many interviewees were still in shock, struggling to make sense of the chaos they had experienced. Almost every story began on the morning of February 24, the day Russian troops invaded, and most could remember it in crystalline detail: a first terrifying bombardment, an anguished early morning call from a relative, or looking out the window at a plume of dark smoke rising on the horizon.

The decision to leave was highly personal, often unrelated to the level of threat. Some interviewees came from places where the war was raging, with nonstop shelling and tanks rolling through the streets. Others, often no less traumatized, traveled from cities largely untouched by fighting.

Many appeared to have left because they could—they had traveled abroad before or knew someone in the West who might help them. Some made a deliberate decision to go abroad. Others did not so much decide as drift out of the country, traveling first to a village or a relative’s home only to find that the fighting was fiercer there, compelling them to head further west and eventually to Poland.

Perhaps most hauntingly, many made their decisions to stay or leave on the flimsiest of grounds, often with little or no information. For instance, one older couple whose daughter left in the first days of the war did not want to accompany her because it would soon be time to plant their garden. Instead, they spent seven terrifying weeks in Mykolaiv, a southern port city that has been among the most devastated, before joining her in Krakow.

Two college-age women had been reluctant to leave, going only when their parents insisted. “I felt I owed it to my family,” one woman explained. “Now I’m not sure I will ever see my family again.”

“How do you make sense of a situation like this?” another older woman asked. “How do you predict? It makes it hard to make any decisions—everything seems so uncertain now.”

The trip itself was almost always harrowing. Trains and train stations were so overcrowded that many women could not squeeze into a carriage or traveled for the better part of a day standing between railroad cars. One woman from eastern Ukraine nearly lost one of her children when her daughter was pushed into a train by a surging mob and her son was dragged down the platform, away from the door.

Trains circled and backtracked to avoid Russian shelling, often taking two or three times as long as usual to reach their destination. And driving was no less chaotic. Drivers, too, had to zigzag and retrace their steps to avoid bombardment. Then many waited in line for a day or two to get through a border crossing.

Displaced Ukrainians arriving in Poland were sometimes overwhelmed by the welcome. Little tent cities sprang up on the Polish side of most border crossings. Local and international nongovernmental organizations, church groups, and individuals dispensed warm clothing, hot food, diapers, medical supplies, and other necessities. Train stations bustled with volunteers. Some new arrivals were directed to group shelters, often in a former supermarket or shopping center—usually a giant hall filled with cots and a plethora of tents offering humanitarian aid.

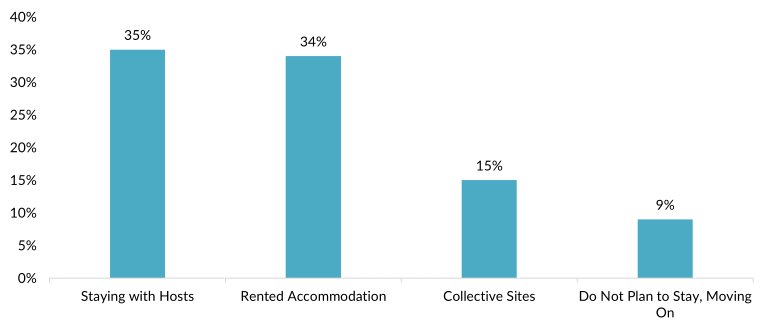

But many stayed only a night or two. Far more found lodging in private homes, some paying rent, others being hosted for free. By early summer, just 15 percent of displaced Ukrainians were living in collective sites, while 69 percent were renting or living with a Polish host, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Current or Planned Accommodation among Displaced Ukrainians in Poland, June 2022

Source: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Refugees from Ukraine in Poland - Profiling Update (June 2022) (Warsaw: UNHCR, 2022), available online.

A Local Sponsor

As the months wore on, some newcomers remained dependent on the sprawling network of humanitarian groups providing aid in cities such as Krakow. Others sought no help at all; they did not want to be a burden or were ashamed to rely on charity. “We don’t need anything,” one retiree told the author, “and many other people need it more.” Still others found an individual to lean on—a relative, a friend or, in some cases, a stranger who had accepted the government subsidy to take them into their homes.

The Polish government does not use the word “sponsor” to describe these local hosts. But the Polish approach, which combines minimal state support with incentives for civil society, is similar in many ways to a policy in place in Canada since the 1970s and one being tried by the United States that relies on private sponsors to resettle humanitarian migrants.

Krakow business manager Ana Michalska was galvanized to help in the early days of the war. She drove supplies to the border and organized parents at her daughter’s school to buy supplies for Ukrainian students. Then one day she noticed a young mother with two children living in what had been an empty apartment across the street and brought them groceries. Olena Tishchenko, recently arrived from western Ukraine, was staying free of charge in an apartment provided by a construction contractor who employed her husband before the war. But she had no idea how to navigate the city or where to turn if she needed help.

When the women learned their daughters were classmates, they took turns picking them up from school. Soon they were spending time together every day. Ana took Olena shopping, first to the grocery store and then the mall, and advised her what to purchase. She also helped her new friend find doctors and translated notices from city government. They communicate half in Ukrainian and half in Polish, with occasional help from Google Translate. By midsummer, they had grown so close that Olena asked Ana to be the godmother of her youngest child. Olena told the author she “loves” life in Poland and intends to stay even after the war is over.

Not all Polish sponsors have grown so close to displaced Ukrainians, and designated sponsors elsewhere have sometimes reported mixed outcomes. But Ana and Olena’s experiences suggest that these relationships can be profoundly meaningful.

Living in Limbo

Among the biggest unknowns are displaced Ukrainians’ plans for the future. Will this be just an interlude, a temporary stay abroad? Or might they be starting a new life in a country where they have no roots and few personal ties? Their legal permission to stay in Poland and other EU Member States was extended in October, but it remains temporary, due to expire in March 2024.

Follow-up conversations with half the 45 original interviewees in late August found that nearly 40 percent of this smaller group had returned to Ukraine. Others longed to go but feared the continuing violence. “I dream of going home,” one young woman said, “as soon as possible. But that’s my heart talking. Logically, I know it’s going to take much longer than I think.”

Many other Ukrainians are still uncertain, with significant consequences for them and the Polish cities where they are living. Should they get jobs or not? Should they learn Polish? Should they send their children to Polish schools? Their uncertainty about the future—would they return to Ukraine, and when—made it difficult to answer all these questions. “I’m getting by day to day,” one young woman explained. “That’s as far as I can see.”

Language Barriers

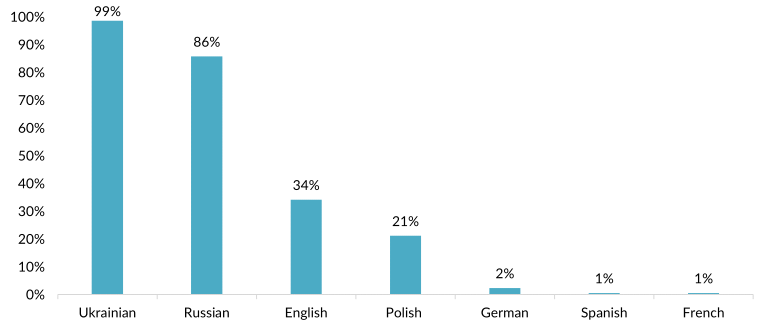

In late spring and early summer, as many as three-quarters of displaced Ukrainians reported they spoke little or no Polish, according to a pair of surveys (see Figure 2). Nationwide, only about 10 percent reported having a good, very good, or excellent command of the language.

Figure 2. Language Proficiency among Displaced Ukrainians in Krakow, Poland, June 2022

Source: Konrad Pędziwiatr, Jan Brzozowski, and Olena Nahorniuk, Refugees from Ukraine in Kraków (Krakow, Poland: Multiculturalism and Migration Observatory, 2022), available online.

The Polish and Ukrainian languages are somewhat similar, allowing some adults to get by without learning Polish, and jobs such as cleaners, kitchen workers, and farmhands may not require language skills. But the two tongues use different alphabets, one Latin, the other Cyrillic, and more highly skilled jobs are likely to require language proficiency.

Most interviewees told the author they wanted to learn Polish, and nearly 75 percent of those surveyed by the MMO team said they were taking steps to learn. But many reported they could not find an available class; every program had waiting lists. And not all newcomers were equally motivated. At a former hospital housing some 300 Ukrainians, language classes struggled to find enough interested residents. Relatively few were working or looking for work, and most felt they did not need Polish, so the shelter stopped offering language instruction.

Employment: Lots of Interest, Little Support

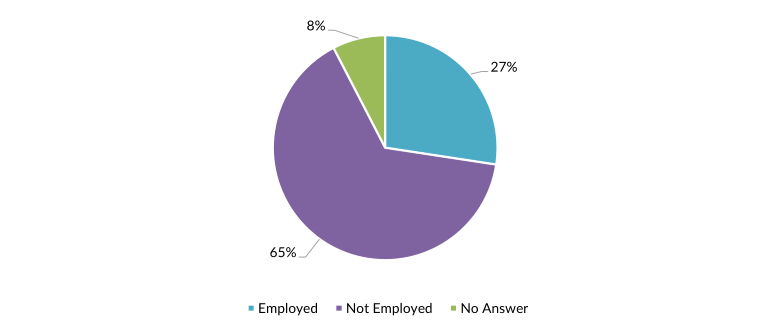

Displaced Ukrainians have the legal right to work in Poland and many seem eager to do so. In April, 63 percent said they were looking for a job, according to a survey by the staffing agency EWL and the University of Warsaw. In August, Poland’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was below 3 percent. And as a group, displaced Ukrainians are unusually well educated, with more than half holding university degrees according to EWL and MMO.

But they also face significant obstacles to employment. According to the MMO survey, only 53 percent had previously been “economically active” in Ukraine, a fairly traditional country, where many women do not expect to work outside the home. Many Ukrainians in Poland care for small children or family members with disabilities and are hesitant to look for work. Two surveys conducted in late spring and early summer found just 20 percent to 30 percent of displaced Ukrainians working in Poland (see Figure 3). By autumn, new calculations by the city of Warsaw suggested that a much higher number—perhaps as many as two-thirds—had found employment of some kind since leaving Ukraine, albeit perhaps temporarily.

Figure 3. Share of Displaced Ukrainians in Krakow Who Were Employed, June 2022

Source: Pędziwiatr, Brzozowski, and Nahorniuk, Refugees from Ukraine in Kraków.

Ukrainians who want to work in Krakow can find relatively little job training. Several nonprofit groups offer job-matching services or teach job-search skills such as how to write a resume and sit for a job interview. Ana Michalska’s friend, Olena Tishchenko, found one of the rare programs teaching actual job skills, and in late summer she enrolled in a six-month course to become an elder-care attendant.

Anecdotal evidence suggests certified service workers such as drivers and cosmetologists, were among the best positioned to find jobs matching their skill sets. Many others struggling to provide for themselves and their children take a step down the job ladder. In Krakow, two certified kindergarten teachers were working at McDonald’s, and a chemical engineer was stocking shelves in a supermarket. “I’m doing what I have to do,” she explained. “I need to feed myself and my children.”

Schools Accommodate Fewer Students than Expected

From the first days of the crisis, Polish schools braced for an influx of Ukrainian students. Budgets were limited and many schools—particularly elite high schools—were already full. Yet estimates suggested that one-third of displaced Ukrainians were school-age children, meaning that Polish schools might need to accommodate as many as 650,000 Ukrainian students.

In fact, numbers have been much lower than expected. In the city of Krakow, some 35,000 Ukrainians have registered to receive government services, which could mean nearly 12,000 children looking to enroll in K-12 education. Yet in May 2022, only about 7,000 were attending Krakow schools.

Where are the students? Some have been studying online in classes provided by schools in Ukraine. A few hundred attend a private school funded by a Ukrainian foundation that offers Ukrainian curriculum in the Ukrainian language and prepares students for Ukrainian end-of-year exams. But many may not be in school at all. Staff at the former-hospital-turned-collective-shelter reported to the author that it can be difficult to persuade mothers to send their kids to school.

The reception offered by schools in the Krakow region varies widely, according to Ukrainian mothers. Some schools, particularly elite high schools, appear to be turning students away due to lack of space. Others offer a warm welcome but lack the staff or skills to accommodate foreign students. Still others have gone out of their way to make provisions for Ukrainian children, raising money from parents and international organizations, hiring extra teachers or teacher’s assistants, and providing trauma counseling, among other services. But even the best schools recognize more could be done.

The biggest challenge is language. Some schools offer dedicated preparatory classes, allowing Ukrainian children to study Polish for a few weeks or months before joining Polish children in regular classes. Other schools provide optional language instruction for a few hours a week. Most rely primarily on Ukrainian-speaking teacher’s assistants who move from classroom to classroom, translating for children who have trouble keeping up.

“The sink-or-swim approach seems to work pretty well,” reported an assistant principal at one Krakow elementary school. “Last year, all 82 of our Ukrainian students were promoted to the next grade.” What is less clear is the effect on high-school students, who may find it harder to learn a new language and often face end-of-year exams necessary to advance or graduate.

What Next? “Nothing to Do but Keep Going”

In October, as Russia launched a new offensive in Ukraine, raising the specter of a nuclear strike and shelling cities far from the front lines, Poles and Ukrainians in Krakow wondered what lay ahead.

Many staff at humanitarian aid points worried about a potential second wave of newcomers, driven by fresh violence or a shortage of heating fuel in Ukraine. Others feared Polish fatigue with humanitarian relief. Even with little overt backlash, it is hard to imagine that fresh arrivals would encounter the same support that greeted those who came last winter. It is also growing harder for even the most eager Poles to address exiles’ evolving needs. Permanent housing, job training, adequate child care, and education are not things that individuals can donate, and all are in increasingly short supply.

Eight months into the crisis, there are more questions than answers for policymakers. Should other nations consider experimenting with the Polish approach, offering minimal cash payments and incentives for civil society? If so, how much assistance is enough, and can there be too much? What lessons can be drawn from the contrast between the experiences of people in Krakow’s group shelters and those hosted in private homes? How might Poland’s experiment with the sponsorship model evolve and be improved?

Meanwhile, displaced Ukrainians grappled with a different calculus: whether and when to return. Some of the Krakow interviewees who have gone back were drawn by patriotism, others by a desire to reunite with their husbands or families. On the other side of the ledger, opportunity beckons in the West, especially for those with more social capital who believe moving would offer a better life for their children. Life in exile can be difficult, particularly for those depending on the kindness of strangers. But Polish prosperity creates a strong pull for those who can navigate the labor market.

The stakes could hardly be higher, for both Poland and Ukraine, which will need skilled and less skilled workers to rebuild when the war ends. Yet most displaced Ukrainians were not thinking that far ahead. “I don’t know what’s going to happen today or tomorrow or even this evening,” a heating and air conditioning technician from Bucha explained. “There’s nothing to do but keep going.”

Sources

Desiderio, Maria Vincenza and Kate Hooper. 2022. Why the European Labor Market Integration of Displaced Ukrainians Is Defying Expectations. Commentary, Migration Policy Institute, October 2022. Available online.

Duszczyk, Maciej and Paweł Kaczmarczyk. 2022. The War in Ukraine and Migration to Poland: Outlook and Challenges. Intereconomics 57 (3): 164-70. Available online.

Jacoby, Tamar. 2022. Displaced: The Ukrainian Refugee Experience. N.p.: Independently published.

Maniatis, Gregory. 2022. America’s Refugee Revolution. Foreign Affairs, July 27, 2022. Available online.

Office of the Capital City of Warsaw. 2022. Aktualne dane na temat kryzysu uchodźczego w Ukrainie. Updated November 1, 2022. Available online.

Pędziwiatr, Konrad, Jan Brzozowski, and Olena Nahorniuk. 2022. Refugees from Ukraine in Kraków. Krakow, Poland: Multiculturalism and Migration Observatory (MMO). Available online.

Polish Press Agency. 2022. Poland's Unemployment Rate at 2.6 Pct in August – Eurostat. Polish Press Agency, September 30, 2022. Available online.

Tilles, Daniel. 2021. Most Poles Opposed to Accepting Refugees and Half Want Border Wall: Poll. Notes from Poland, August 26, 2021. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. Refugees from Ukraine in Poland - Profiling Update (June 2022). Warsaw: UNHCR. Available online.

Wojdat, Marcin and Paweł Cywiński. 2022. Urban Hospitality: Unprecedented Growth, Challenges and Opportunities: A Report on Ukrainian Refugees in the Largest Polish Cities. N.p.: Union of Polish Metropolises. Available online.

Zymnin, Anatoliy. 2022. Radio Poland: 63% of Ukrainian Refugees Want to Work in Poland: Survey. EWL, April 13, 2022. Available online.