You are here

Mexican Migration to Canada: Temporary Worker Programs, Visa Imposition, and NAFTA Shape Flows

Mexican heritage on display during a parade in Toronto. (Photo: Can Pac Swire)

Emigration from Mexico to Canada has been considerably less examined than to the United States, which is by far the overwhelming destination for Mexican migrants. Yet this migration reveals some significant differences: Mexicans who obtain permanent resident status tend to have similar educational attainment as other immigrant groups in Canada, a significant contrast with those in the United States, where Mexicans have lower levels of education.

However, the number of Mexicans gaining permanent resident status (about 3,000 or so) is much smaller on an annual basis than the flow of temporary foreign workers. The Canadian agricultural sector, for example, employs about 24,000 temporary Mexican laborers each year through a formal worker program. (Unlike the United States, Canada does not have a large unauthorized population from Mexico or any other country in the workforce.) While the bilateral agricultural worker agreement dates to 1974, the migration relationship between Canada and Mexico was further strengthened by the 1994 North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which provided greater employment mobility for Mexican and Canadian professionals.

Until mid-2009, Mexicans were able to travel to Canada without a visa. At that time, Canada’s Conservative government, in response to increasing Mexican asylum claims, imposed a visa requirement on all Mexican visitors. Although the visa requirement was removed in December 2016 by the Liberal government, the policy put a strain on the Canada-Mexico migration relationship.

This article analyzes the effects of the visa requirement on permanent and temporary flows. It also describes the demographic profiles and entry status of Mexican permanent residents in Canada, drawing from the authors’ analysis of a restricted-access government dataset to compare Mexicans to the overall immigrant population. Canada prioritizes highly skilled, educated individuals for permanent residency, granting this status to a selective group of Mexicans. More than half of all working-age Mexican permanent residents in Canada have a university degree, and almost 75 percent have at least some postsecondary education. However, most of the Mexicans who enter Canada on temporary status—particularly those in the agricultural sector—are unable to obtain permanent residency and the benefits of that status.

Migrating to Canada

Immigrants arrive to Canada as permanent residents in one of three streams: economic, family, or humanitarian. Canada prioritizes economic migration rather than family reunification: about 60 percent of new permanent residents in Canada are selected on the basis of education and work experience or a family member’s economic attributes. In comparison, only 12 percent of new green-card holders in the United States in 2017 received an employment-based visa. The inverse is true for family ties: about two-thirds of new green-card holders in the United States obtain their status through family reunification, which is about triple the proportion in Canada. In addition, Canada has a narrow definition of which family members can be sponsored; siblings and adult children do not normally qualify for sponsorship. In recent years, the number of new permanent residents in Canada has varied from 250,000 to 300,000—less than 2 percent of whom are Mexicans. Historically, permanent residence was a distinct visa path from temporary status in Canada, and most new permanent residents did not previously reside or work in Canada.

Canada has several visa programs for individuals to visit or reside on a temporary basis as students or workers. Recently, the number of temporary laborers contributing to the Canadian economy has increased. Many work in low-skilled occupations, have lower education levels, and are unable to qualify for permanent residence as economic migrants. Agricultural laborers from Mexico and 11 Caribbean countries may enter Canada under the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) year after year as temporary foreign workers, leaving their family abroad. Migrant-rights groups have called for agricultural workers and their families to receive permanent resident status, but the government has not shown any plans to change its policies for these lower-skilled migrants. In recent years, between 10 percent and 25 percent of adults who enter Canada through a temporary foreign worker program eventually become permanent residents. However, the proportion of low-skilled or agricultural laborers who ultimately obtain permanent status is much lower. While some programs allow low-skilled or semi-skilled workers to obtain permanent resident status in provinces with labor shortages—including Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba—eligibility requirements remain strict and the number of visas available are minimal.

After living in Canada for three years, permanent residents are eligible to apply for citizenship. As in the United States, individuals born in Canada receive citizenship at birth. Immigrants in Canada have higher naturalization rates than in the United States, and individuals with permanent resident status are conceived as long-term residents who will become citizens and are therefore offered programming to assist with their integration. However, individuals on temporary work permits do not generally receive these benefits.

The Advent of the Visa Requirement amid Rising Asylum Claims

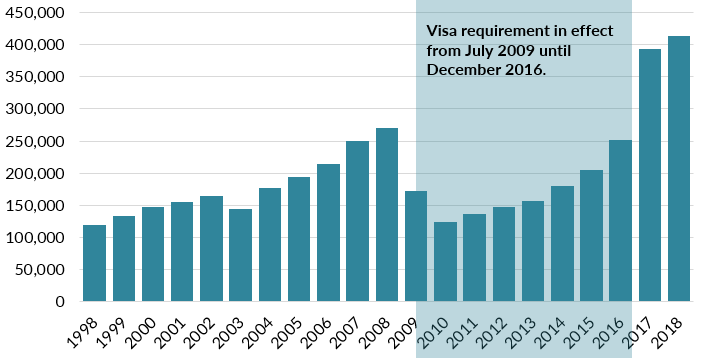

The decision to impose a visa on Mexican citizens in 2009 dramatically decreased the number of Mexicans who traveled to Canada, falling to 124,000, in 2010, from 271,000, in 2008. Travel rebounded after the visa was lifted, with 393,000 arrivals from Mexico in 2017 (see Figure 1). This was the first year that the numbers exceeded the 2008 total.

Figure 1. Number of Residents of Mexico Entering Canada, 1998-2018

Source: Statistics Canada, “Non-Resident Travelers Entering Canada, by Country of Residence (excluding the United States)” Table 24-10-0003-01, updated March 8, 2019, available online.

Asylum Seekers and Refugee Claimants

Visa policy in Canada often responds to influxes of refugee claims or concerns about security and passport integrity. Since 2001, visa requirements have been imposed on citizens of Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Costa Rica, Mexico, the Czech Republic, and several Caribbean and southern African countries. Mexico was the last Latin American country to receive a visa requirement. In the last ten years, the Canadian government lifted visa requirements for nationals of Croatia, Chile, the Czech Republic, Taiwan, Bulgaria, Romania, and the United Arab Emirates.

In the years preceding the visa imposition in 2009, increasing numbers of Mexican nationals made refugee claims in Canada. The introduction of a visa requirement allowed government officials to refuse applications of individuals who they suspected may request asylum and dissuaded potential refugee claimants from applying. At the same time, the hassle of submitting a visa application discouraged Mexicans who would have otherwise visited Canada from doing so, resulting in a significant reduction of travelers (see Figure 1).

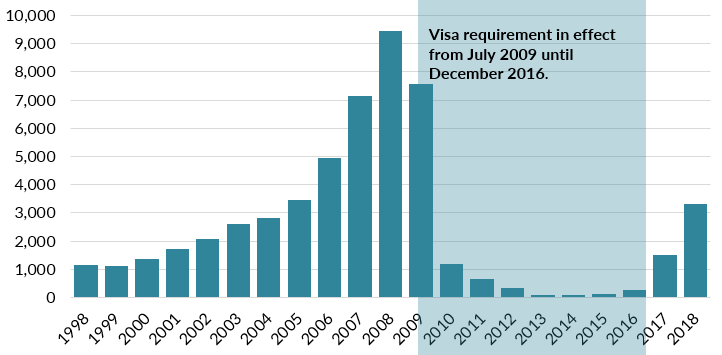

Data on the number of refugee requests from Mexicans show the decrease in new claims after the visa requirement was implemented (see Figure 2). Although these claims dropped from about 9,500 in 2008 to around 1,000 in 2010, the post-2009 period was characterized by increasing violence and insecurity in Mexico. Still, the visa requirement did not halt all claims. Some Mexicans making claims post-visa imposition may have entered Canada before July 2009 or traveled without official documents. Once the visa requirement was lifted in 2016, the number of claims rose again, but to levels similar to those observed near the late 1990s and early 2000s. Today, while citizens of 144 countries or territories require visas before entering Canada, Mexicans can travel visa-free after obtaining an Electronic Travel Authorization (eTA).

Figure 2. Refugee Claims from Mexico in Canada by Year, 1998-2018

Sources: Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), Facts and Figures: Immigration Overview—Permanent and Temporary Residents (Ottawa: CIC, 2008), available online; CIC, “Refugee Claimants by Top 50 Countries of Citizenship, 2006-15,” dataset 10.2, updated May 3, 2017, available online; Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), “Canada—Asylum Claimants by Top Twenty-Five Countries of Citizenship (2018 ranking), Claim Office Type and Claim Year, January 2015-December 2018,” updated March 12, 2018, available online.

Temporary Foreign Workers

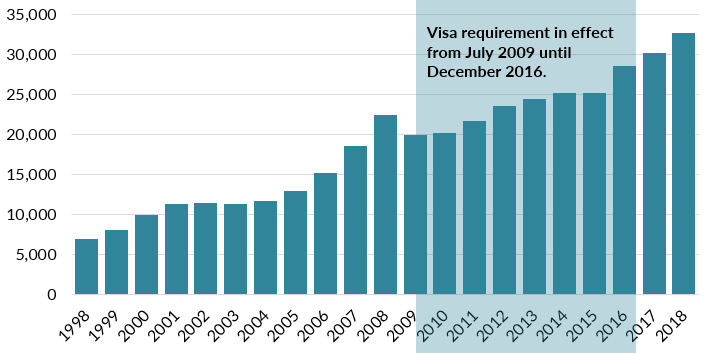

While the number of Mexicans traveling to Canada decreased significantly while the visa was in effect, the number of temporary foreign workers continued to rise. In 2018, 32,770 Mexicans entered Canada on work permits, setting a new record. This represented 10 percent of all temporary foreign workers in Canada, and only India had more nationals in Canada on temporary worker status. The overwhelming majority of Mexicans enter through SAWP. In 2019, the Mexican government projects that 26,000 Mexicans will work in Canada through the agricultural worker program. Canada’s increasing reliance on temporary labor from Mexico and other countries has continued unabated over the last 20 years, with a slight decrease following the 2008-09 global economic slowdown.

Many reports have highlighted the precarious conditions experienced by these migrant laborers. When compared to permanent residents, temporary foreign workers in Canada generally are tied to employer-specific job permits and feel discouraged from reporting poor working conditions or health concerns as this may result in early termination of a contract or eliminate the possibility to return the following year. Low-skilled migrant laborers also endure lengthy periods of separation from their families, who are generally not permitted to enter Canada. While advocacy groups have called for policy changes, only minor tweaks to the bilateral agreement on agricultural labor have been made.

NAFTA and Other Temporary Work Permits

In addition to SAWP, Mexico and Canada have a special migration relationship defined under NAFTA. The trade pact’s implementation in 1994 changed the economic relationship and enhanced travel and cooperation between the two countries. The agreement included labor mobility provisions for professionals in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. These provisions, found in Chapter 16 of the agreement, largely remain intact in the proposed successor deal negotiated in 2018, the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which has yet to be ratified by any of the three countries. The provisions allow professionals in 63 occupations to work in Canada after receiving a job offer, without going through the full immigration procedures where employers must demonstrate their need to hire someone from another country. In 2016, 691 Mexicans obtained this status—significantly less than the 23,893 agricultural laborers who arrived in the same year.

In addition to the specific agreements for labor mobility found in NAFTA and SAWP, Mexicans with job offers in Canada or who are transferred to Canada by their multinational employer obtain work permits through regular channels. The total number of Mexicans who obtain work permits before entering Canada continues to rise (see Figure 3). Individuals who make a refugee claim in Canada are also authorized to work while the asylum process is underway (these figures are not included in Figure 3 as they overlap with the number of refugee claims presented in Figure 2).

Figure 3. Mexican Temporary Foreign Workers in Canada by Year, 1998-2018

Note: These data do not include “other” work permits for humanitarian cases.

Sources: CIC, Facts and Figures: Immigration Overview—Permanent and Temporary Residents; CIC, “Temporary Foreign Worker Program Work Permit Holders by Top 20 Countries of Citizenship and Sign Year, 2006-15,” dataset 3.3, updated May 3, 2017, available online; CIC, “International Mobility Program Work Permit Holders by Top 20 Countries of Citizenship and Sign Year, 2006-2015,” dataset 3.4, updated May 3, 2017, available online; IRCC, “Temporary Residents: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders—Monthly IRCC Updates,” updated March 12, 2018, available online.

International Students

In recent years, the number of Mexicans studying in Canada has also increased. From 2000 to 2012, between 3,000 and 5,000 Mexican students studied in Canada annually—even during the years of the visitor visa imposition. Since 2012, the numbers have grown, and at the end of 2018, there were 7,835 Mexicans on study permits. Canada allows international students who complete postsecondary education to obtain a Post-Graduate Work Permit and search for employment. International students who find employment after graduation also have a much higher chance of eventually obtaining permanent residence, as economic immigration programs give additional points to work and education completed in Canada. Others find a spouse or partner in Canada and eventually migrate through the family class.

Permanent Residents

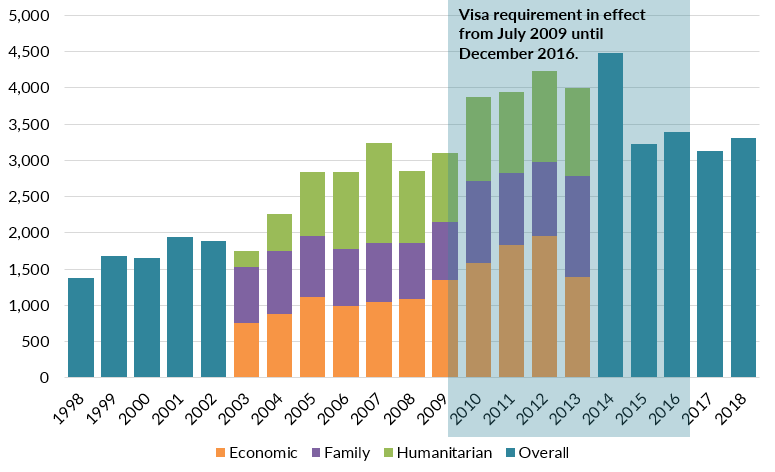

While Mexico is one of the top source countries for temporary foreign workers in Canada, it is not among the top sources of new permanent residents. Before the mid-2000s, there were fewer than 2,000 Mexicans arriving in Canada per year, representing less than 1 percent of new immigrants. However, in the 2000s, the number increased modestly, still representing less than 2 percent of all new permanent residents. Since 2014, the number of new permanent residents from Mexico has decreased, returning to levels observed in the mid-2000s. Forty percent of all recent permanent residents are from three Asian countries: India (17 percent), the Philippines (14.5 percent), and China (9 percent).

Figure 4. New Mexican Permanent Residents in Canada, 1998-2018

Note: Entry status (economic class, family class, or humanitarian), obtained through Permanent Resident Landing File (PRLF) data, is available only for the period 2003-13.

Sources: IRCC, "Permanent Residents—Ad Hoc IRCC (Specialized Datasets)," updated April 18, 2017, available online; IRCC, “Canada—Admissions of Permanent Residents by Country of Citizenship, January 2015-December 2018,” dataset, updated January 18, 2019, available online.

Demographic Profile of Mexican Permanent Residents in Canada

Detailed demographic data on Canada’s permanent residents can be obtained through the Permanent Resident Landing File (PRLF), a restricted-access dataset provided by Statistics Canada and Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) that offers information on the 2.75 million individuals who obtained permanent resident status from 2003-13. Data for other years are not available. The authors of this article analyzed the data to provide more information on the demographics of all immigrants, and the Mexican subset, immigrating to Canada as permanent residents during this period.

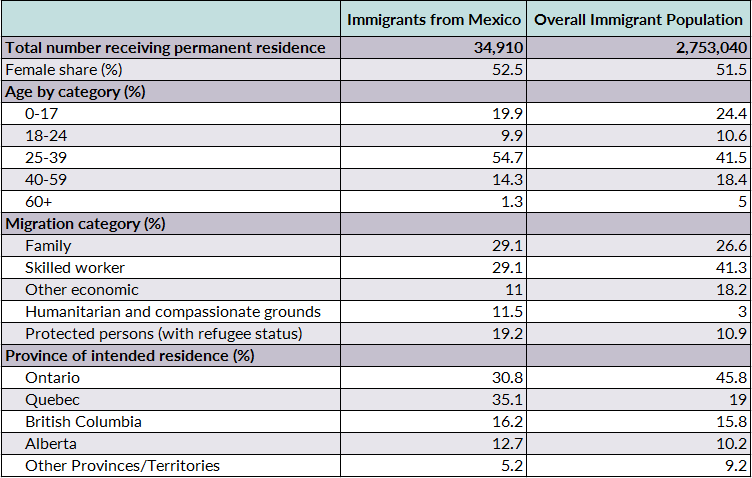

In contrast to the predominately male flow of Mexican temporary foreign workers, 52.5 percent of Mexicans who received permanent resident status in Canada during this 11-year period were female. Mexican immigrants are more likely than migrants to Canada overall to be in the 25-39 age group, with nearly 55 percent of Mexicans in this age group as compared to 41.5 percent for those from other countries.

Table 1. Selected Demographic Characteristics of New Permanent Residents to Canada, 2003-13

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Source: Statistics Canada and IRCC, “Permanent Resident Landing File,” updated May 7, 2017.

From 2003-13, just over 30 percent of Mexicans who obtained permanent residence did so through a humanitarian visa program: either by having a refugee claim accepted (19.2 percent) or by humanitarian and compassionate grounds—cases in which a refugee claim was not accepted, but government officials found other humanitarian grounds that merited a grant of permanent residence (11.5 percent). This is higher than the 14 percent for all immigrants. The assessment and the subsequent granting of permanent residence usually takes a few years to complete, which is why larger numbers of Mexicans continued to receive permanent residence status after the visitor visa requirement was imposed. Humanitarian cases made up 13 percent of Mexicans who immigrated to Canada in 2003 and 23 percent in 2004, but then increased to between 29 percent and 43 percent from 2005 to 2013.

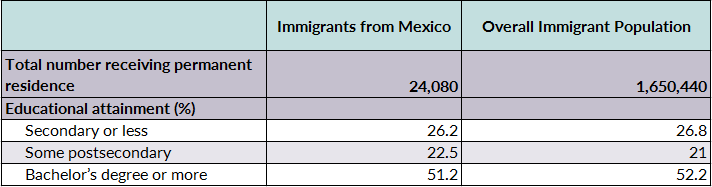

About 40 percent of Mexicans immigrated through an economic migration program, and almost 30 percent immigrated through sponsorship by a close family member. When compared to all immigrants entering Canada during this time period, Mexicans were more likely to immigrate to Quebec and less likely to immigrate to Ontario. The educational profile of working-age Mexican immigrants is similar to the overall trend of immigrants to Canada, even though a smaller proportion qualified through an economic migration program. As Table 2 indicates, more than half of all working-age Mexican immigrants have a university degree, and almost 75 percent have at least some postsecondary education.

Table 2. Educational Background of Working-Age New Permanent Residents (ages 25-59) to Canada, 2003-13

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Source: Statistics Canada and IRCC, “Permanent Resident Landing File,” updated May 7, 2017.

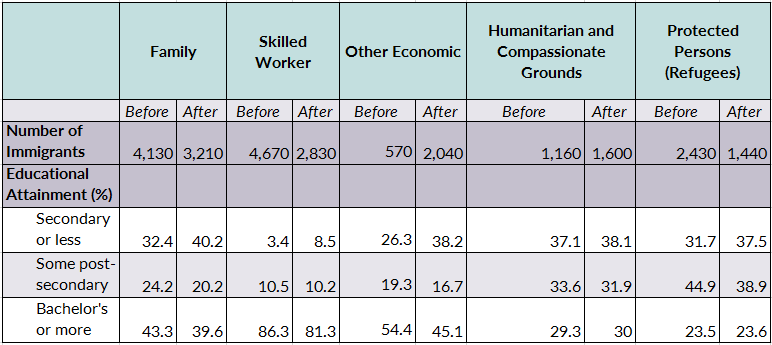

Table 3 further explores the education levels of the working-age Mexicans who obtained permanent residency during the 2003-13 period, comparing those who arrived between 2003-09, labeled as “before” the visa requirement, and 2010-13, labeled as “after.” It is worth noting that individuals who obtained permanent residence “after” the visa requirement was in effect may have applied beforehand, given processing times.

These data also show that the majority of Mexicans who obtained permanent resident status had postsecondary education, irrespective of entry category, and more than 80 percent who entered through the federal or Quebec Skilled Worker programs had at least a university degree. In recent years, the rise of other economic migration programs, including the Provincial Nominee Program and Canadian Experience Class program, has allowed more migrants with lower education levels to enter as economic migrants. After 2009, the number of Mexicans who qualified under such economic programs increased fivefold, and the proportion without university degrees also increased. While fewer Mexicans who immigrated as refugees or through other humanitarian programs had a university education, more than 60 percent had some postsecondary education.

Table 3. Educational Attainment of Working-Age Mexican New Permanent Residents to Canada (ages 25-59), Before and After the 2009 Visa Imposition, (%), 2003-13

Notes: Before represents immigrants receiving legal permanent residence between 2003-09, while after represents those receiving that status during the 2010-13 period. All numbers rounded to 10.

Source: Statistics Canada and IRCC, “Permanent Resident Landing File,” updated May 7, 2017.

Opportunities and Challenges for Mexican Migrants

Temporary and permanent migration from Mexico to Canada has increased in recent years. Even as tourists and asylum seekers from Mexico declined during the period the visa requirement was in effect, the number of new permanent residents and temporary foreign workers and students continued to rise, more rapidly for temporary arrivals.

Canada remains selective in the number and type of migrants who qualify for permanent residence, prioritizing education, professional experience, and other criteria. As a result, the number of new Canadian permanent residents from Mexico each year is much smaller than the number of temporary foreign workers. Canada’s selective immigration programs, including the Skilled Worker program, make it difficult for individuals with lower levels of education to qualify for permanent residence or transition from temporary status. Although there are some opportunities for immigration through family reunification or humanitarian programs, the reduced number of Mexicans making asylum claims since 2009 and limited opportunities for family migration suggest it is more likely that the proportion of new permanent residents from Mexico will return to the lower levels observed before the visa imposition.

The analysis presented in this article was conducted at the Quebec Interuniversity Centre for Social Statistics (QICSS), which is part of the Canadian Research Data Centre Network (CRDCN). QICSS receives support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, Statistics Canada, the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Société et culture, the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé, and the Quebec universities. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the CRDCN or its partners.

Sources

Baglay, Sasha. 2012. Provincial Nominee Programs: A Note on Policy Implications and Future Research Needs. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 13(1), 121-141.

Basok, Tanya. 2000. He Came, He Saw, He Stayed. Guest Worker Programs and the Issue of Non-Return. International Migration 38 (2): 215-38.

---. 2002. Tortillas and Tomatoes: Transmigrant Mexican Harvesters in Canada. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Basok, Tanya, Danièle Bélanger, and Eloy Rivas. 2014. Reproducing Deportability: Migrant Agricultural Workers in Southwestern Ontario.Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (9): 1394-1413.

Bloemraad, Irene. 2006. Becoming a Citizen in the United States and Canada: Structured Mobilization and Immigrant Political Incorporation. Social Forces 85 (2): 667-95.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 2008. Facts and Figures: Immigration Overview—Permanent and Temporary Residents. Ottawa: Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Available online.

---. 2015. Refugee Claimants by Top 50 Countries of Citizenship, 2006-15. Dataset 10.2. Updated May 3, 2017. Available online.

---. 2016. International Mobility Program Work Permit Holders by Top 20 Countries of Citizenship and Sign Year, 2006-15. Dataset 3.4. updated May 3, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. Temporary Foreign Worker Program Work Permit Holders by Top 20 Countries of Citizenship and Sign Year, 2006-15. Dataset 3.3. Updated May 3, 2017. Available online.

Escalante, Sebastian. 2004. Disrupting Mexican Refugee Constructs: Women, Gays, and Lesbians in 1990s Canada. In Canadian Migrant Patterns from Britain and North America, ed. Barbara J Messamore. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

Ferrer, Ana M., Garnett Picot, and W. Craig Riddell. 2014. New Directions in Immigration Policy: Canada’s Evolving Approach to the Selection of Economic Immigrants. International Migration Review 48 (3): 846-67. Available online.

Flores, Sara María Lara and Jorge Pantaleón. 2015. Trabajadores mexicanos en la agricultura de Quebec. In Los programas de trabajadores agrícolas temporales : ¿una solución a los retos de las migraciones en la globalización?, eds. Martha Judith Sánchez Gómez and Sara María Lara Flores. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales/Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT). Available online.

Foster, Jason. 2012. Making Temporary Permanent: The Silent Transformation of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. Just Labour 19: 22-46. Available online.

Gilbert, Liette. 2016. Visas as Technologies in the Externalization of Asylum Management: The Case of Canada’s Entry Requirements for Mexican Nationals. In Externalizing Migration Management: Europe, North America and the Spread of “Remote Control” Practices, ed. Ruben Zaiotti. London: Routledge.

Giorguli-Saucedo, Silvia E., Víctor M. García-Guerrero, and Claudia Masferrer. 2016. A Migration System in the Making: Demographic Dynamics and Migration Policies in North America and the Northern Triangle of Central-America. Mexico City: El Colegio de México, Center for Demographic, Urban, and Environmental Studies. Available online.

Goldring, Luin. 2010. Temporary Worker Programs as Precarious Status. Canadian Issues/Thèmes canadiens Spring 2010: 50-54. Available online.

Griffith, Andrew. 2017. Building a Mosaic: The Evolution of Canada’s Approach to Immigrant Integration. Migration Information Source, October 31, 2017. Available online.

Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada. 2016. Permanent Residents—Ad Hoc IRCC (Specialized Datasets). Updated April 18, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. Canada—Asylum Claimants by Top Twenty-Five Countries of Citizenship (2018 ranking)—Claim Office Type and Claim Year, January 2015-December 2018. Updated March 12, 2018. Available online.

---. 2017. Temporary Residents: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders—Monthly IRCC Updates. Updated March 12, 2018. Available online.

---. 2017. Canada—Admissions of Permanent Residents by Country of Citizenship, January 2015-December 2018. Dataset. Updated January 18, 2019. Available online.

---. 2019. Canada—Study Permit Holders with a Valid Permit on December 31st by Country of Citizenship, 2000-18. Updated January 18, 2019. Available online.

Jackson, Emily. 2017. "Chaos and Confusion": What’s at Risk If NAFTA Professional Visas Disappear. Financial Post, December 29, 2017. Available online.

Martin, Patricia, Annie Lapalme, and Mayra Roffe Gutman. 2015. Réfugiés et Demandeurs d’asile Mexicains à Montréal: Actes de Citoyenneté Au Sein de l’espace Nord-Américain? ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 12 (3): 603-28.

Mueller, Richard E. 2005. Mexican Immigrants and Temporary Residents in Canada: Current Knowledge and Future Research. Migraciones Internacionales 3 (1): 32-56. Available online.

Preibisch, Kerry. 2010. Pick-Your-Own Labor: Migrant Workers and Flexibility in Canadian Agriculture. International Migration Review 44 (2): 404-41.

Prokopenko, Elena and Feng Hou. 2018. How Temporary Were Canada’s Temporary Foreign Workers? Population and Development Review 44 (2): 257-80. Available online.

Silverman, Stephanie J. and Amrita Hari. 2016. Troubling the Fields: Choices, Consent, and Coercion of Canada’s Seasonal Agricultural Workers. International Migration 54 (5): 91-104.

Statistics Canada. 2019. Non-Resident Travelers Entering Canada, by Country of Residence (excluding the United States), Table 24-10-0003-01. Updated March 8, 2019. Available online.

Statistics Canada and Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada. N.d. Permanent Resident Landing File. Updated May 7, 2017.

Verduzco, Gustavo. 2008. Lessons from the Mexican Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program in Canada. In Mexico-U.S. Migration Management: A Binational Approach, eds. Agustín Escobar Latapí and Susan F. Martin. Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books.

Villegas, Paloma E. 2013. Assembling a Visa Requirement against the Mexican “Wave”: Migrant Illegalization, Policy and Affective “Crises” in Canada. Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (12): 2200-19.