You are here

Mexico: The New Migration Narrative

Mexico's contemporary migration narrative is being rewritten as a result of significant developments within the country, as well as evolving trends among its neighbors to the north and south. New economic, demographic, and political realities have coalesced to dramatically slow the large Mexican flows that had made their way to the United States over recent decades. And Mexico now is also confronted with the task of re-integrating many of its citizens and their U.S.-born children, and is reshaping its legislative and political reality to deal with its role as a country of transit and, presumably, increasingly of destination.

For the first time ever, transit migration from Central America to the United States is a significant policy priority in Mexico today—both from a security and human-rights standpoint. Prior to 2010, mention of migration into Mexico or of transit migration through the country was relatively marginal. But the Mexican government's adoption of a new migration law in 2011 was a ground-breaking recognition not only of the scale of transit migration but also of government accountability to ensure migrants' rights, including those of transmigrants. Nevertheless, implementation of this law may prove to be a significant challenge, and managing migration that comes from the south, whether temporary or permanent, has become increasingly hazardous and a source of regional tension.

Mexico's relations with the United States, where roughly one in ten of its citizens currently resides—more than half in unauthorized status—have evolved somewhat as well. Border enforcement, deportations, and migrant deaths dominated Mexico's migration agenda with the United States in the years immediately following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, putting strain on the bilateral relationship. While those irritants remain in to an extent, new political realities have emerged. Chief among them: the prospect of U.S. immigration reform, which stalled earlier this decade, was back on the table in Congress in a serious way in spring 2013, holding the potential to bring an estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants, including approximately 6.8 million from Mexico, out of the shadows and into the mainstream of U.S. life.

Mexico, whose migration history from the 1970s onward was largely one of flows to the United States, now embodies several dimensions of the migration phenomenon: emigration, still primarily to the United States; transit migration, mainly by Central Americans headed northward; and not insignificantly, temporary and permanent immigration from Central America and other countries.

This updated profile examines Mexican migration to the United States and Mexicans in the United States, U.S. immigration policy affecting Mexican immigrants, Mexico's role as a transit country, remittances, government policy toward the Mexican diaspora, migration into Mexico, and refugee and asylum policy in Mexico.

Mexican Migration to the United States

History of Flows: World War II to Economic Crisis of Late 2000s

Although many new trends are emerging, Mexico remains tied to its northern neighbor through a decades-long history of migration that dates back to World War II, when U.S. officials approached the Mexican government in search of temporary agricultural labor. Through the resulting Bracero program (which spanned 1942 to 1964), Mexico supplied an estimated 4.5 million workers to the United States, peaking at almost 450,000 workers per year during the late 1950s.

Although the Bracero program was halted, “go north for opportunity" was an idea that remained deeply embedded in the Mexican mindset. Migration networks—relatives, friends, and employers, in particular—established in the 1940s, ‘50s, and early ‘60s laid foundations for sustaining Mexico-U.S. migration. And until recently, U.S. enforcement measures did little to curb the flows drawn by opportunities in the U.S. labor market, and the widely held perception of a more promising future in “el norte.”

After the Bracero program ended, U.S. border enforcement began to increase; in small measure at first, then rising in the mid-1990s, and taking on new urgency after 9/11. Over time, Mexican migration, which used to be mostly circular and temporary, changed. Although the shift in behavior began gradually during the 1980s, the move became more permanent after stepped-up border enforcement began in the mid-1990s, initiated through well-known Border Patrol actions such as Operation Gatekeeper. Increased enforcement made it more difficult and costly (in terms of smuggler fees among other factors) for Mexicans to cross back and forth.

Thus, the number of Mexicans settling permanently in the United States annually—with or without legal status—increased steadily from the 1970s onward. The Mexican population settling in the United States grew from less than 250,000 per year in the 1980s to well above the 300,000 mark in the 1990s, and approached the half-million mark in the early 2000s. The size of the Mexican immigrant population doubled from 2.2 million in 1980 to 4.5 million in 1990, and more than doubled to 9.4 million in 2000, at which point Mexican immigrants made up 29.5 percent of all immigrants in the United States. According to some calculations, the Mexican immigrant population surpassed the 12 million mark in 2007—just before the onset of the economic recession; the Census Bureau estimated the Mexican-born population at 11.7 million in 2011, the most recent year for which figures are available.

Mexicans have become an increasing share of the U.S. immigrant population, which overall has risen sharply over the past four decades. Over the course of the 1970s, Mexican immigrants became the largest immigrant group in the United States, with about 16 percent of the total immigrant population in 1980. Today, they represent 29 percent of all immigrants to the United States—a larger share than the eight next top origin countries combined.

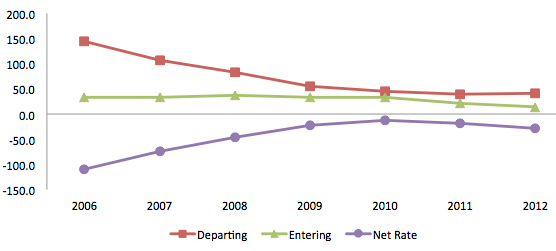

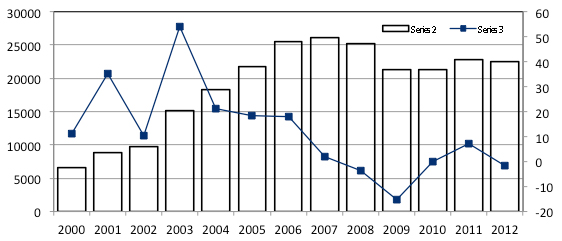

Current Flows and Implications of Near-Zero Net Migration

Since 2010, there has been a net standstill in the growth of the Mexican population in the United States, as a result of increased outflows and reduced inflows that manifested themselves after the onset of the softening of the U.S. construction sector in 2007 and recession the following year (see Table 1 and Figure 1). Population estimates for the Mexican born in the United States in 2011 are not significantly different from the 2010 total. According to official Mexican statistics, an estimated 317,000 Mexicans crossed the country's northern border to enter the United States in 2011, down 36 percent from the estimated 492,000 individuals in 2010.

Mexico's National Survey of Occupations and Employment (Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo, ENOE) reports that Mexico's immigration rate, which calculates the number of people (Mexican or not) who move to Mexico from another country, most of whom are return migrants, has dropped from 3.7 per 1,000 in fall 2008, to 2.1 per 1,000 in fall 2012 (see Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States). While data from Mexico's Border Survey of Mexican Migration show decreased flows of unauthorized migrants by quarter from 2008 to 2011, a slight uptick was detected during the first two quarters of 2012.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||

|

The near-zero net migration from Mexico to the United States that manifested itself in 2010 represents a new trend. There is no one single factor accounting for this change. One driver is the decrease in outmigration, a confluence of economic factors in the United States and Mexico—still high unemployment in the former, paired with Mexico's improving economic stability, modest growth (in per capita terms), and ongoing social improvements. Increased immigration enforcement at the U.S.-Mexico border and within the U.S. interior also have played a role.

The U.S. recession and labor market trends may have caused a longer-term shift in migration flows. Whether this change is cyclical or structural remains to be seen, and will be put to a test once the U.S. economy experiences a full recovery and returns to dynamic growth. Another factor will be the growth pattern of the Mexican economy and its ability to incorporate still rising numbers of labor force entrants and the unemployed.

Stepped-up immigration enforcement in the United States has also had a direct effect on Mexicans, who represent 59 percent of all unauthorized immigrants in the United States. The increased pace of deportations that began during the Bush administration and have continued under President Obama has been felt most keenly by Mexicans. In 2011, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) deported 391,953 individuals, 75 percent (nearly 294,000) of whom were Mexican.

Drivers of Mexico-U.S. Migration

Migration from Mexico to the United States is primarily economically motivated. Nominal wage differentials have been hovering for years at about a 10-to-1 ratio, in favor of the United States, for manual and semi-skilled jobs. Moreover, a dynamic U.S. economy led to a strong demand for workers in seasonal agriculture, high-turnover manufacturing, construction, and the service industry. On the Mexican side, there have been enormous economic transformations, but not pronounced enough to absorb the growing working-age population.

Until the 1970s, Mexican migrants originated mainly from the rural areas of central Mexico and were mostly confined to the U.S. agricultural sector, largely in the U.S. southwest. After the 1970s, Mexican migrants also originated from small, medium, and large cities, with a wide range of work experiences, skills, and qualifications, and found employment in the United States in construction, food processing, sundry services, and agriculture, which remains a mainstay employment niche.

More recently, U.S.-bound migration has originated in nearly every corner of the country and has spread throughout the United States, especially in California and Texas. The south, southeast, and other nontraditional emigrant regions of Mexico rapidly also became "high emigration areas." According to 2011 Census Bureau American Community Survey data, the main industries attracting Mexican-born immigrants are service and personal care; construction, extraction, and transportation; and manufacturing, installation, and repair.

The U.S. recession and slow economic growth since 2007 seem to be changing previous patterns. U.S. demand for immigrant workers (Mexican or not) has dropped substantially, and circumstances in Mexico might be perceived as more favorable—though perhaps not enough to significantly alter the status quo. Mexico has a growing middle class, but it is not yet a middle-class society. Employment in informal sectors remains significant, and Mexico's minimum wage has experienced, on average, negative growth in real terms over the past few decades.

Poverty, in terms of income capacity (pobreza de patrimonio)—a telling indicator of Mexico's economic distress—continues to affect roughly half of the population. Even though poverty has slightly decreased in relative terms, from 53.6 percent of the population in 2000 to 51.2 percent in 2010 (the most recent year for which statistics are available), it affects more people (52.7 million, a net increase of 5 million since 2000). Estimates of extreme poverty (pobreza alimentaria, or inability to buy basic food) also show a similar pattern for the same period, falling from 21.4 percent (18.6 million Mexicans) to 18.8 percent (21.2 million).

On Mexico's demographic side, the number of working-age people will continue to expand well into the 2030s. The pace of growth in the number of working-age Mexicans has become controversial as fertility decline has stalled in recent years. Estimated net additions to the working-age population between 2010 and 2030 could fluctuate between 10 million and 15 million or more.

It is nearly impossible to gauge future U.S. demand for immigrant labor, and more so if future economic growth uncertainties continue. As far as the capacity of the Mexican economy to absorb a demographically slowing Mexican labor supply, the prospects are relatively promising for the moment, opening a window of opportunity that can seek to harness the results of an improving educational picture and rising skill levels.

Although not a driver of Mexico-U.S. migration, U.S. immigration and enforcement policies will also have an impact on the quantity, modalities, and types of future Mexican migration.

Changing Composition of Mexican Migration Flows

Mexican migration flows have changed in many ways over the years. Recent indicators suggest that the characteristics of migrants are becoming as diverse, in terms of migrants' origin and educational and occupational levels, as the characteristics of the Mexican population at large. According to Mexican municipal-level data, less than a dozen municipalities out of over 2,400 failed to register some type of migratory activity—defined as households with at least one migrant abroad (whether or not the household receives remittances), or households with at least one returnee—between 2005 and 2010.

Mexicans continue to migrate to the United States mainly in search of work. As of 2011, 88 percent of Mexican migrants in the United States were in the 16-64 age group, according to the Mexican Migration Monitor. The share of Mexican-born immigrants ages 16 and over participating in the civilian labor force in the United States (70 percent) is slightly higher than that of the total U.S. immigrant population of similar ages (67 percent) and U.S.-born population of those ages (63 percent).

The migration flows include greater numbers of professionals and skilled persons. According to migration experts José Luis Ávila and Rodolfo Tuirán, who examined Census Bureau Current Population Survey data, the number of Mexican immigrants with some level of professional education or equivalent experience more than doubled between 2000 and 2010, from a little over 400,000 to more than 1 million; and the number with postgraduate education increased at a higher rate, from 62,000 to almost 151,000.

Between 1997 and 2007, the number of Mexicans with a bachelor's degree or higher rose at an average annual growth rate of 6 percent in Mexico, but the number of Mexican-born professionals living in the United States rose at the rate of 11 percent, according to researchers Elena Zúñiga and Miguel Molina. If this trend continues, at some point it may become a factor hampering Mexico's potential economic and social development.

Increasingly, the distinction between circular and settled migrants is becoming blurred. Indeed, many permanent migrants began their journey to the United States as circular migrants, often although not exclusively as unauthorized immigrants.

Circular migrants tend to be younger and predominantly male, while settled migrants are more evenly split between men and women, more urban, and better educated (meaning more than eight years of schooling).

Mexicans in Canada

Canada's Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP), which began over 40 years ago, originally relied on workers from Caribbean countries, but has included Mexican workers since 1974. Mexicans currently account for roughly two-thirds of total workers in this program. Between 2009 and 2011, a little more than 18,000 Mexicans came, on average, to work temporarily on Canadian farms.

Although the Mexican immigrant population in Canada is tiny compared to the population in the United States, it has increased mainly since the 1990s, more than doubling from 22,000 in 1991 to about 50,000 in 2006, the most recent year for which data are available. Approximately 3,200 Mexican immigrants arrived in Canada for permanent residence in 2007; 2,800 in 2008; 3,100 in 2009; 3,900 in 2010; and 3,600 in 2011, according to official Canadian estimates.

Economist Richard Mueller has argued that a good portion of Canada's Mexican population consists of the descendants of Canadian Mennonites who settled in Mexico in the 1920s and have since “returned,” enabled in part by claims to Canadian citizenship. However, Mueller finds that the number of non-Mennonite Mexican born has grown faster.

Some recent arrivals likely include Mexicans who entered through Canada's points system for highly skilled immigrants. In 2005, enterprising Canadian immigration lawyers saw an opportunity when border enforcement became a hot political topic in the United States. They began advertising legal migration to Canada, both in Mexico and Arizona.

Also, as fear of deportations became stronger, many Mexicans asked for asylum in Canada. Similarly, as the Mexican government stepped up its fight against organized crime and violent drug gangs, more Mexicans fled home and asked for asylum in Canada. Thus, Mexico became Canada's top source country for asylum applications in 2008. Although claims from Mexico almost tripled between 2005 and 2008, from 3,446 to 9,527, only 11 percent of claims reviewed in 2008 were accepted.

In response to an apparent abuse of asylum applications, Canada in July 2009 began requiring Mexican citizens to have visas before they can travel to Canada. Since then asylum applications have decreased. In 2011, there were fewer than 1,000 refugee claimants from Mexico.

Immigration Policy in the United States and Mexico and Its Consequences

As a reflection of the importance attached to policy as potential drivers of migration flows, their characteristics, and modalities, the Mexican government closely monitors changes in U.S. immigration policy. In early 2013, all eyes were focused on the improved prospects in Congress for a major overhaul of U.S. immigration law that held the promise of some form of legalization for the nation's estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants.

The current circumstances are quite different from those prevailing in 2001, when momentum on immigration reform was associated with high-level bilateral talks and negotiations between the administrations of Presidents George W. Bush and Vicente Fox.

Today, U.S. internal political, economic, and demographic factors are driving the push for reform, perhaps none more significant than growing pressures in both the Democratic and Republican parties to deliver on this issue. Vocal business demands for immigrant workers, rejection of self-deportation as a viable strategy, and growing public support for legalization also are playing key roles in driving the debate. Nevertheless, as of this writing, it remained an open question whether reform would be accomplished and if so, what shape it would take.

The Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 was the first serious attempt to curtail illegal migration, but its promise of increased enforcement did not take hold until years later and migration simply continued in various irregular forms, in the context of a permissive attitude by both countries. IRCA's legalization programs, which granted status to 2.7 million unauthorized immigrants, had an important long-term unintended consequence: its contribution to the transformation of Mexican migration from a predominantly circular pattern into a more permanent one.

Together with earlier events, including U.S. Border Patrol operations in 1993-94, U.S. enactment in 1996 and beyond of robust immigration-control policies prompted the Mexican government to openly seek a routine dialogue with Washington.

Although the dialogue enhanced information exchanges, the effectiveness of consular protection, and the expansion of certain forms of cooperation at the Mexico-U.S. border, it did not prevent the expansion of Border Patrol operations or the enactment of the restrictive Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) in 1996.

This legislation, together with the strong message sent in 1994 by California's Proposition 187, convinced many permanent Mexican residents to naturalize as a way to protect themselves from curtailments of many of their social rights.

This restrictive climate also motivated Mexico to pass a law in 1998 allowing its citizens to have dual citizenship.

As the United States stepped up border enforcement, one of the unintended consequences has been an increase in the number of deaths as migrants take ever-greater risks to reach the United States. This has become an important source of tension in the U.S.-Mexico relationship, and has also strengthened Mexico's determination and resolution to protect its nationals abroad.

Since the Bracero program, but particularly since the 1980s, Mexico has built out its consular network in the United States. As of 2013, Mexico had 51 consulates tasked with reaching out to all Mexicans, regardless of their legal status.

Among the policies the Mexican government implemented, and continues to implement, is the issuance of hundreds of thousands of matrícula consular identification cards for migrants. After 9/11, Mexico increased its efforts to provide these ID cards. Nearly 1 million matrículas were issued in 2003. The matrícula, which is valid for five years, had many more uses — from getting driver's licenses to opening bank accounts at hundreds of U.S. financial institutions—than is currently the case.

In parallel, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) provided a more detailed framework for bilateral immigration dialogue and understandings.

High-Level Bilateral Relations and Migration Since 2000

In February 2001, Presidents Fox and Bush engaged their administrations to find mutually acceptable responses to a lingering migration issue that often had placed the two countries at odds.

The high-level discussions centered on regularizing Mexicans already residing in the United States, establishing a guestworker program, enhancing border enforcement, and increasing the number of visas available for Mexicans. Expectations of arriving at a far-reaching agreement were high until the September 11 attacks.

The approach to manage the Mexico-U.S. migration relationship radically changed: After 9/11, security, border control, and counterterrorism shaped the new reality and discourse governing U.S. immigration policymaking. The Bush administration, especially during its last years, oversaw stricter enforcement of existing laws, reinforced boundaries—real and virtual—with Mexico, and conducted highly visible worksite enforcement raids.

It took Mexico some time to realize that 9/11 had dramatically changed the U.S. government's priorities and, consequently, that U.S.-Mexico relations were entering a new era. In 2005-06, at the end of President Fox's term, the Mexican government made an unprecedented effort to update Mexico's migration policy on topics such as “undocumented migration” (the term used in A Message from Mexico about Migration), border and regional security, human smuggling and trafficking, and international cooperation. The result was codified in a high-level message in which Mexico advanced a key concept of “shared responsibility”—indicating its willingness to do its part with regard to migration management.

In particular, Mexico accepted explicit responsibility for improving economic and social opportunities in the country, recognizing the important implications migration represents for its development, through a “more directly productive use of remittances” as well as enhanced relations with Mexicans abroad. Mexico also committed to encourage and ease the return and reintegration of Mexicans into their origin communities.

This new approach had many aims, including securing new U.S. engagement to manage Mexican migration bilaterally, and influencing legislative discussions on various immigration reform bills introduced in Congress in 2006 and 2007. This approach did not have the intended effects, however.

Probably as a reaction to such developments, newly elected President Felipe Calderón in December 2006 opted to use a subtler, more low-key approach on migration matters. The government posited that development and job creation in Mexico were key to breaking Mexico's migration cycle. However, many Mexicans felt as though economic development and job creation were still lagging by the end of his tenure in 2012.

Nevertheless, the Calderón administration did seem aware that U.S. policy was unlikely to change, even though his government had prioritized national security concerns and the fight against drug trafficking and organized crime.

The Calderón administration, looking at the same time toward Mexico's southern border with Guatemala, made several attempts to reinforce Mexico's border patrol and modernize migration facilities to better handle transit migration. Several programs were also enacted to regularize labor migration in the southern regions.

The Obama administration, upon taking office in 2009, placed its focus on enforcement, keeping up the Bush administration's record pace of removals, to the dismay of immigrant communities and immigrant-rights advocates.

In December 2012, Enrique Peña Nieto was sworn in as Mexico's president after a campaign in which migration was not a central issue nor does it appear to be one of his administration's top priorities. Consequently, it seems that the strategy of the new administration to deal with the U.S.-Mexico migration issue will not be one of open and direct confrontation and intervention in the U.S. immigration debate. Certainly, migration continues to be a very important and visible component within Mexico's complex relationship with the United States, and the Peña Nieto administration will probably continue the mostly discreet migration approach of the Calderón administration.

The Peña Nieto administration also faces the challenges of implementing Mexico's 2011 migration law. The task will not be an easy one due to the reality on the ground regarding the rule of law in general and the real possibility of full fruition of migrants' rights enshrined in the law vis-a-vis principally immigrant detention conditions, duration of detention, and access to translators. The administration will also face difficult choices if it attempts to put some order at the southern border, like beefing up border personnel and modernizing control infrastructure, or if it embraces an attitude of de facto free migration.

Although it is too early to know whether the Peña Nieto administration brings a new approach to this issue of migration, it will be heavily influenced by U.S. legislative action on immigration reform. Nevertheless, the likelihood that any U.S. immigration policy in the near future could provide an explicit answer to the Mexico-U.S. migration issue is low.

Transit Migration and its Management

Historically, the seasonal economic migration of Guatemalans to Mexico was mostly seen as a regional and localized phenomenon, with no major national spillovers.

However, civil wars in the 1980s in El Salvador and Nicaragua, and Guatemala's 36-year war that began in 1960 meant that many displaced Central Americans transited through Mexico to seek asylum or look for jobs in the United States. Over the years, migrants from other parts of the world, particularly from South America (e.g., Ecuador) have used Mexico as a transit country. The number of transmigrants rose through the 1990s and into the first part of the 2000s, to the point that it became a cause of concern for the Mexican government.

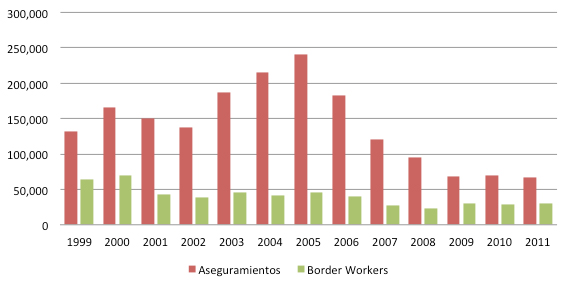

More recently, as is the case with Mexican migration to the United States, transit migration declined with the onset of economic difficulties in 2007 and recession the following year (see Table 2 and Figure 2). Between 2009 and 2011, transit migration appeared to have leveled off, with preliminary 2012 data, however, indicating an increase. This increase is in line with more non-Mexican unauthorized migrants (most of whom are Central American) being apprehended at the U.S. border. There are also many more Central American unaccompanied minors being apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border than in the past.

One may estimate the flows that come from the south by looking at two numbers. The first is the number of border workers, primarily Guatemalans. Between 2001 and 2006, the number of the permits issued to border workers hovered between 40,000 and 45,000. Following a seemingly inexplicable drop (perhaps related to the looming recession) in 2007, they have fluctuated between 25,000 and 30,000.

The second way to measure transit migration flows is the number of aseguramientos (also recently known as alojados, migrants in shelters), which are primarily apprehensions or seizures of potentially deportable foreigners. (Note: these are counted as events, not as individuals. In these figures are also counted those Central Americans who resort to voluntary repatriation). Aseguramientos generally increased between 1999 and 2005, but have declined relatively steeply since 2007. In 2011, the number of aseguramientos (66,583) was roughly one-quarter of its peak of 240,269 in 2005 (see Table 2 and Figure 2). On average, around 90 percent of these events ended in actual deportations.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||

|

The distribution of these apprehensions by country of origin shows clearly that Central Americans constitute the overwhelming majority of those intercepted by Mexican authorities. Of the 88,500 aseguramientos reported in preliminary 2012 data, 45.3 percent were from Guatemala, 32.6 percent from Honduras, 14 percent from El Salvador, and at some distance Nicaragua and Ecuador with 0.8 percent each. The remaining 6.5 percent was divided among all other countries. With minor variations this distributive pattern has been the norm for years.

In the 1990s, transit migration gained importance as the United States reinforced security at its border with Mexico. This in turn put pressure on Mexico to control its southern border so that fewer Central Americans could enter the United States irregularly via Mexico.

Rather than concentrating on controlling its southern border, Mexico chose to increase interior enforcement by, for example, setting up checkpoints along major highways, and by expanding detention facilities. Mexico more than doubled the number of such facilities from 22 to 48, between 2000 and 2008. It also stepped up deportations, since 2006 signing agreements with Guatemala and other Central American countries that allow Mexico to turn over all unauthorized Central Americans to their countries of origin.

The strategy of interior enforcement may have had its successes. However it also became apparent that there were insufficiencies—in training and numbers—of border and migration personnel, especially when smuggling and trafficking of humans and drugs began to increase, following the stricter U.S. border controls in the 1990s and Mexico's fight against drug cartels in the second half of the 2000s.

Despite executive orders that outline detainees' rights and procedural obligations, many human-rights and civil-society groups, including Mexico's National Human Rights Commission, have complained and issued reports pointing out that many detention facilities are overcrowded and unhygienic, and that detainees receive poor treatment. They also point out that corruption among government officials has not been eliminated and that organized criminal groups prey on many migrants.

Partly as a response to such reports, Mexico's National Migration Institute (Instituto Nacional de Migración or INM) in 2006 began implementing new detention procedures that allow citizens of Central American countries to sign a repatriation form that may expedite their removal from Mexico. Later on, in 2008, Mexico passed legislation that decriminalized irregular presence. And in 2011, Mexico enacted an unprecedented new migration law as a more explicit answer to deteriorating circumstances for migrants in transit, recognizing its own obligation to ensure humane conditions for migrants through Mexico. In the debate leading to the passage of this law, the Mexican government also weighted the consideration that its policies should be congruent with what it asks from the U.S. government in terms of treatment of Mexican migrants.

Indeed, transit through the country became hazardous and unauthorized migrants became highly vulnerable and were subject to serious and frequent victimization. The most notorious and highly publicized incident occurred in August 2010, when 72 migrants were found dead in Tamaulipas state (100 miles from Brownsville, TX) at the hands of one of many drug cartels known to extort migrants passing through their territories.

This shocking event eventually led to the approval by the Mexican Congress—in a rare unanimous vote—of the migration law that was enacted in May 2011. This law is meant to reverse the pattern of calamities suffered by migrants in transit. It is also intended to fully comply with the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (ICMW), ratified by Mexico in 1999, and that entered into force in 2003.

The law is unambiguous in its defense of the rights of migrants irrespective of their legal status, be they in transit or with Mexico as their destination. The law also aims to ensure equality between Mexican natives and immigrants, recognizes the acquired rights of long-term immigrants, and promotes family unity and migrant integration. It also intends to facilitate the international movement of people, to meet the country's labor needs, and to facilitate the return and reintegration of Mexican emigrants.

It is not yet possible to judge the full range of the law's impacts, given the law's broad objectives and the delayed release of its operable regulations or reglamento in November 2012. However, the law has already reduced bilateral tensions with Central American governments. With regulations only recently issued, there will be an institutional learning curve as INM agents and other law enforcement officials must relearn procedures for enforcing immigration laws.

Enforcing these changes could prove particularly difficult given the climate of heightened security concerns, generalized violence, and weak professionalization of Mexican enforcement agencies. However, the law represents an important step in Mexico's acknowledgment of the basic rights to which unauthorized migrants are entitled.

Immigrants in Mexico and Return Migration

Immigration to Mexico is meager compared to emigration of its nationals and transit migration.

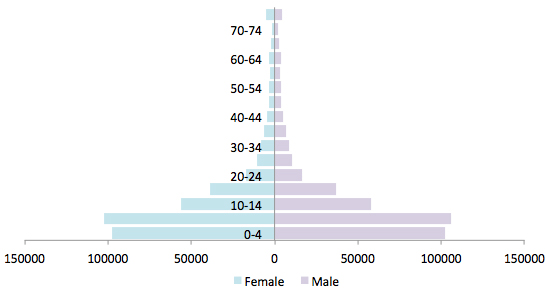

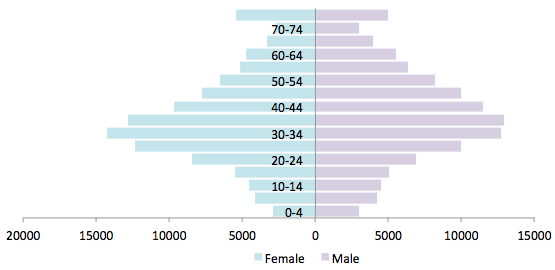

Mexico's foreign-born population almost doubled between 2000 and 2010 (493,000 to 961,000), and comprised just under 1 percent of the total population in 2010 (the most recent year for which data are available). However, more than three-quarters of immigrants were born in the United States, and the vast majority of the U.S. born were children were under the age of 15 (see Table 3 and Figures 3a and 3b). According to a Pew Hispanic Center report using Mexican Census data, around 500,000 U.S.-born children resided in Mexico in 2010. Some have been raised and resided in Mexico since a young age, but others have returned more recently to Mexico and experience difficulties integrating into Mexican society and its educational system. Mexico is also home to a small number of U.S. retirees.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

The age structure of the non-U.S. foreign-born population is concentrated in the working ages, as is the case among most immigrant populations worldwide. It is widely acknowledged that this population contributes greatly, if selectively, to the country's economy, considering its relatively high levels of education or qualifications. Based on administrative records of almost 250,000 foreign-born residents ages 16 years and older, migration experts Ernesto Rodríguez Chávez and Salvador Cobo estimate that in 2009, 33.3 percent worked; 20.1 percent were pensioners; and 6.3 percent were students. The remaining 40.2 percent did not specify their activity. Among the foreign born, it is presumed that there is a relatively small component of foreign born who had adjusted their status from refugee to permanent resident.

Guatemala, in a very distant second place after the U.S.-born population, accounted in 2010 for 3.7 percent of all foreign born, followed by Spain, with 2 percent. The remaining 17.5 percent came from the rest of the world.

The Importance of Remittances and the Diaspora

The Mexican diaspora in the United States, which includes people who self-identify as Mexican immigrants or who trace their family ancestry to Mexico, was estimated at 34.8 million in 2011—the third-largest diaspora group in the United States after Germans and Irish immigrants and their descendants.

Remittances, like migration, had important but mostly regional effects until the 1980s, when emigration became more common across Mexico. Since then, recorded remittances increased steadily in volume and importance, from $6.6 billion in 2000 to $26.1 billion in 2007, then decreased in 2012 to $22.4 billion, according to the Bank of Mexico.

The severe recession in the United States, which has especially affected sectors with a large number of Mexican immigrants such as construction, has dampened remittance flows. Remittances inflows to Mexico declined 3.6 percent in 2008 but more steeply in 2009 (-15.7 percent) to $21.2 billion. Thereafter, they stabilized and have even compensated for some of the lost ground: In 2011, remittance inflows were 7 percent higher than in 2010 (see Table 4 and Figure 4).

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||

|

Remittances have important macroeconomic and indirect effects. Although they represent less than 4 percent of Mexico's GDP, remittances have become the second largest source of foreign income, after oil exports, and ahead of tourism or foreign direct investment. The stronger and most direct effects, however, occur at the local and household levels. Thus, the drop might mean a relapse into poverty for many families, particularly in rural areas, and a slowdown of economic activity mostly felt at the community level.

Researcher Jesús Arroyo's findings on the use of remittances in 2007 reflect what has been a long-term pattern: About three-quarters of remittances were spent on everyday expenses, like food and rent, about 8 percent on house acquisition and improvement, 6 to 7 percent on debt repayment, and 3 to 4 percent on land acquisition, agricultural implements, and business-related expenses. The remainder included other expenses and purchases of items such as cars and electric appliances.

Since 1986, the government has been trying to encourage a more development-oriented and productive use of remittances. In 1999, earlier programs evolved into the Three-for-One Program (Programa 3 x 1), which matches every dollar from a migrant with one dollar each from federal, state, and municipal governments. In the 2005-08 period, between two-thirds to three-quarters of program funds went to infrastructure projects—from road pavement to school improvements—and other social works, including public buildings and church restoration. However, the program accounts for less than 1 percent of all remittance dollars.

In 1990, the Program for Mexican Communities Abroad (Programa para las Comunidades Mexicanas en el Exterior or PCME) was established with the objectives of helping migrants maintain cultural links with their country, encouraging investments in their communities of origin, and helping them to secure their rights while abroad.

In 2003, PCME and another initiative were merged to create the Institute of Mexicans Abroad (Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior or IME). The Institute includes all Mexicans communities, namely the hometown associations of Mexican nationals and U.S. citizens of Mexican origin. In addition to previous objectives, one of IME's goals is to collect proposals from with the aim of improving these individuals' living conditions abroad. (For more on IME, see the MPI report Protection through Integration: The Mexican Government's Efforts to Aid Migrants in the United States).

These programs reflect the importance the Mexican government attaches to the Mexican and Mexican-American populations, as well as their economic and political importance.

Refugee and Asylum Policy

At very specific junctures in history, Mexico has had generous policies regarding refugees and asylum seekers, most notably in the 1930s for exiles of the Spanish Civil War, and in the 1980s and 1990s for people fleeing their political systems in several South and Central American countries.

In 2000, Mexico ratified the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. In March 2002, the Mexican government began adjudicating asylum claims on its own, thus replacing the eligibility determinations of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in place since 1982.

In 2011, Mexico granted refugee status to 262 persons. One-third (88) came from El Salvador, and one-third (89) were from other Latin American countries (Honduras, Colombia, and Guatemala, with roughly 30 refugees each). It is also possible for asylum applicants to be granted humanitarian visas and remain legally in Mexico.

A common complaint by rights advocates is that there is lack of transparent regulation regarding the adjudication process. However, within the Mexican Commission to Help Refugees (Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados or COMAR), a coordination unit has been established to better monitor and improve the process of adjudication of the status of refugees.

Changing Contexts, Changing Concerns

Two to three decades from now, the number of workers entering and leaving the Mexican labor market may level off, which would be a fundamental departure from the demographic reality from the 1940s forward that pushed millions of Mexican workers in search of better economic opportunity outside their country.

Until then, and in light of the inability of the Mexican labor market to fully absorb workers and pay wages that sustain better living standards, unless the U.S. economy stagnates for a sustained period of time, the lure of migration will remain, albeit weakened from its peak in the 2000s. Together, the recession and the earlier 9/11 attacks have fundamentally changed the history and the narrative of Mexican migration.

In some respects, Mexico has already undertaken efforts to retain its population instead of encouraging and accepting its traditional role as a long-time labor force provider for the rest of North America. The Mexican government has expanded and improved safety nets for the entire population. Access to health care services improved during de Calderón administration through the expansion of the Seguro Popular program. The Peña Nieto administration has been able to forge a promising Pacto Por Mexico (Pact for Mexico) with major political parties. This pact is a pledge to move toward universal health care, a pension for all adults, unemployment insurance, and other life insurance provisions. These plans, if successfully implemented, may reduce emigration pressures.

The pact calls for specific actions and reforms that would put the economy on a course of growth of at least 5 percent annually, which would be higher than what the country has experienced in over three decades. Were Mexico to follow the envisioned path, it could change the balance sheet of potential benefits and drawbacks that would-be migrants must weigh before deciding whether to the leave the country.

Educational reform is also a key component of the pact, although its focus does not include English language and proficiency. Still, English is being introduced in educational curricula nationwide, and many point to such actions as improving would-be migrants' chances for success.

In terms of migration-related government entities, at the end of the Calderón administration, a Unit for Migration Policy (Unidad de Política Migratoria, UPM) was created with the aim of improving coherence between the different migration actions of the Mexican government, and to more effectively comply with the objectives of the 2011 migration law.

Regardless of the outcome of U.S. legislative efforts to reform immigration law, Mexico-U.S. migration undoubtedly will continue to be an important and pressing bilateral issue that will demand continued diplomatic and political attention, as will the issue of reintegration of return migrants, including deportees.

Contexts have also changed structurally for transit migration. With net migration from and through Mexico at very low levels, and the U.S. border far less porous than in the past, ensuring that transit migration is a regular and safe process and reassessing control of Mexico's southern border will be priorities.

Transit migration and attention to migrants' rights (in no small measure) made heavy imprints on Mexico's 2011 migration law, but the law ignores other migration dimensions. An integral discussion of goals or strategies on matters of emigration, transit migration, immigration, or return migration has yet to take place.

Slowly but steadily, Mexican and Central American flows have created a regional migration system that places Mexico squarely in a greater context — a regional one.

There are no easy policy responses to emerging migration trends in Mexico. The challenges ahead are serious; responses are difficult; uneasy trade-offs will certainly be involved; and no guaranteed solutions are in sight.

Sources

Alba, Francisco. 2011. Hacer virtud de la necesidad. Hacia una nueva generación de políticas para la migración México-Estados Unidos. October 2011. Este País 246: 8-12.

Alba, Francisco. 2010. Rethinking Migration Responses in a Context of Restriction and Recession: Challenges and Opportunities for Mexico and the United States. Law and Business Review of the Americas 16 (4): 659-72.

Alba, Francisco. 2010. Respuestas mexicanas frente a la migración a Estados Unidos, in Migraciones Internacionales, eds. Francisco Alba, Manuel Angel Castillo and Gustavo Verduzco. El Colegio de México, pp. 515-546.

Alba, Francisco. 2009. Migration Management: Policy Options and Impacts on Development in Mexico. Unpublished study prepared for the OECD Development Centre, Paris.

Alba, Francisco. 2008. The Mexican Economy and Mexico-U.S. Migration, in Escobar Mexico-U.S. Migration Management, eds. Latapí, Agustín and Susan F. Martin. Lexington Books, pp. 33-59.

Alba, Francisco. 2007. La reconsideración de la política migratoria internacional in México: los retos ante el futuro, Gustavo Vega. El Colegio de México, pp. 57-74.

Alba, Francisco. 2003. Del diálogo de Zedillo y Clinton al entendimiento de Fox y Bush sobre migración, in México-Estados Unidos-Canadá, 1999-2000, ed. Bernardo Mabire. México: El Colegio de México, pp. 109-164.

Alba, Francisco and Manuel Ángel Castillo. 2012. New Approaches to Migration Management in Mexico and Central America. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Alba, Francisco, Manuel Ángel Castillo and Gustavo Verduzco, eds. 2010. Migraciones Internacionales, Los grandes problemas de México, vol. III. El Colegio de México.

Armijo Canto, Natalia. 2011. Frontera sur de México: los retos múltiples de la diversidad, in Migración y seguridad: nuevo desafío en México, Natalia Armijo Canto, ed. Mexico: CASEDE, pp. 35-51.

Arroyo, Jesús. 2010. Migración, remesas y desarrollo regional: trinomio permanente, in Migraciones internacionales, Francisco Alba, Manuel Ángel Castillo and Gustavo Verduzco, eds. El Colegio de México, pp. 227-270.

Arvizu Arrioja, Juan. 2011. Disminuye migración a EU por mejor calidad de vida: SEGOB. El Universal, July 11, 2011.

Ávila, José Luis and Rodolfo Tuirán, 2012. La migración internacional calificada: el crecimiento de mexicanos a Estados Unidos. Paper presented at the Seminar Las políticas migratorias en México y el Mundo. SEGOB and El Colegio de México, November 5-6, 2012.

Banco de México. Sistema de Información Económica (SIE), Indicadores Económicos. Available online.

Castillo, Manuel Angel. 2012. Extranjeros en México, 2000-2010. July 2012. Coyuntura Demográfica, 2: 57-61.

Cave, Damien. 2012. American Children, Now Struggling to Adjust to Life in Mexico. The New York Times. June 18, 2012. Available online.

Cave, Damien. 2011. Better Lives for Mexicans Cut Allure of Going North. The New York Times. July 5, 2011. Available online.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 2012. Facts and figures 2011-Inmigration overview: Permanent and temporary residents. Available online.

Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos de México 2005. [Mexican National Human Rights Commission] (CNDH). Informe Especial de la Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos sobre la situación de los derechos humanos en las estaciones migratorias y lugares habilitados del Instituto Nacional de Migracíón en la república mexicana [Special Report of the National Human Rights Commission on the Human Rights Situation in Migrant Detention Centers of Mexico's National Migration Institute]. Mexico City: CNDH.

Commission on Immigration Reform and Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. 1997. Binational Study on Migration Between Mexico and the United States. Mexico. Available online.

Consejo Nacional de Población. 2012. índices de intensidad migratoria México-Estados Unidos, 2010. Mexico. Available online.

Cornelius, Wayne A. 2001. Death at the border: Unintended consequences of U.S. immigration control policy. December 2001. Population and Development Review 27 (4): 661-685.

Corona, Rodolfo and Rodolfo Tuirán. 2008. Magnitud de la emigración de mexicanos a Estados Unidos después del año 2000. Papeles de Población. July-September 2008. pp. 9-38.

Délano, Alexandra. 2011. Mexico and Its Diaspora in the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Escobar Latapí, Agustín and Susan F. Martin, eds. 2008. Mexico-U.S. Migration Management. Lexington Books.

Fernández de Castro, Rafael. 2006., Seguridad y migración: un nuevo paradigma. Foreign Affairs en Español 6 (4): 2-9.

Giorguli, Silvia, Selene Gaspar and Paula Leite. 2006. La migración mexicana y el mercado de trabajo estadounidense. Consejo Nacional de Población. Mexico. Available online.

González-Barrera, Ana, Mark Hugo Lopez, Jeffrey S. Passel and Paul Taylor. 2013. The Path Not Taken: Two Thirds of Legal Mexican Immigrants are not U.S. Citizens. Pew Hispanic Center. February 2013. Available online.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2012. Boletín de prensa núm. 330/12. Tasas brutas de migración internacional y saldo neto migratorio según periodo 2006-2012". Available online.

Instituto Nacional de Migración (National Migration Institute). Estadísticas Migratorias. Various issues. Mexico. Available online.

Leite, Paula, and Silvia Giorguli. 2009. Las políticas públicas ante los retos de la migración mexicana a Estados Unidos. CONAPO, Mexico.

Lopez, Mark Hugo and Daniel Dockterman. 2011. U.S. Hispanic Country of Origin Counts for Nation, Top 30 Metropolitan Areas. Pew Research Hispanic Center. Available online.

Meissner, Doris, Donald M. Kerwin, Muzaffar Chishti, and Claire Bergeron. 2013. Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery, Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Mexican Migration Monitor. 2012. Tomás Rivera Policy Institute and El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.

Mueller, Richard. 2005. Mexican Immigrants and Temporary Residents in Canada: Current Knowledge and Future Research. January 2005. Migraciones Internacionales 3 (1): 32-56. Available online.

Papademetriou, Demetrios. 2012. Migration Meets Slow Growth. Finance and Development. September 2012. pp. 18-22.

Passel, Jeffrey, D'Vera Cohn, and Ana González-Barrera. 2012. Net Migration from Mexico Falls to Zero-and Perhaps Less. Pew Hispanic Center. April 2012.

Payán, Tony. 2011. Ciudad Juárez: la Tormenta Perfecta, in Migración y seguridad: nuevo desafío en México. Natalia Armijo Canto, ed. Mexico, CASEDE, pp. 127-143.

Rodríguez Chávez, Ernesto and Salvador Cobo. 2012. Extranjeros Residentes en México. Centro de Estudios Migratorios, INM, SEGOB.

Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. 2005. México frente al fenómeno migratorio (Mexico and the Migration Phenomenon). October 2005.

Simanski, John and Lesley M. Sapp. 2011. Immigration Enforcement Actions: 2011. DHS Office of Immigration Statistics Annual Report, September 2012. Available online.

Sin Fronteras. 2009. Situación de los derechos humanos de las personas migrantes y solicitantes de asilo detenidas en las Estaciones Migratorias de México, 2007-2009. Mexico City: Sin Fronteras. Available online.

Suro, Roberto, and René Zenteno. 2012. Collapse and Convalescence: The Great Recession and Mexican Migration Flows. Mexican Migration Monitor.

Terrazas, Aaron, Demetrios G. Papademetriou and Marc R. Rosenblum, 2011. Evolving Demographic and Human-Capital Trends in Mexico and Central America and their Implications for Regional Migration, Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Tuirán, Rodolfo, and José Luis Ávila. 2010. La migración México-Estados Unidos, 1940-2010, in Migraciones Internacionales, Francisco Alba, Manuel Angel Castillo and Gustavo Verduzco, eds. El Colegio de México. pp. 93-134.

The U.S.-Mexico Migration Panel. 2001. Mexico-U.S. Migration: A Shared Responsibility. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace/Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México.

Zúñiga, Elena, and Miguel Molina. 2008. Demographic Trends in Mexico: The Implications for Skilled Migration. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.