You are here

Millionaire Migration Rises and Heads to New Destinations

Luxury cars in front of a hotel on Dubai's Palm Jumeirah. (Photo: iStock.com/slava296)

Wealthy individuals have bought property and secured residence in new countries in increasing numbers in recent years. Briefly stalled by the COVID-19 pandemic, the trend could resume as the result of the easing of public health-related border restrictions, global unrest following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and economic turbulence. While tiny in comparison to most migration streams, the number of people with a net worth above U.S. $1 million moving internationally more than doubled from 51,000 in 2013 to 110,000 in 2018. After a dip during the pandemic, about 88,000 high-net-worth individuals were projected to relocate by the end of 2022, and a record-setting 125,000 transnational millionaires were anticipated to be on the move in 2023, according to projections by Henley and Partners, a consulting firm.

Millionaires and other affluent migrants tend to transcend the debates that guide traditional immigration policy discussions. Unlike migrants arriving as low-skilled workers, asylum seekers, or via other streams, affluent immigrants rarely compete for jobs with the native born, tend not to burden health-care systems and other social services, and likely invest money in local economies. Yet they may also squeeze real estate markets, exacerbate local socioeconomic divides, and deprive their origin countries of investment.

Historically, the largest shares of millionaire migrants have tended to be Chinese and Indian nationals, but the fallout from Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine—including an economic freefall and growing domestic unrest—has prompted thousands of Russians to leave their native country and relocate from Western Europe, where many had been living previously. According to the UK Ministry of Defence, around 15,000 millionaires had fled Russia as of June.

This article examines the changing and growing trends in migration of wealthy people. It first provides a background to millionaire migrants, considers the opportunities and challenges they pose to various stakeholders in sending and receiving countries, and considers future developments surrounding their migration trends.

Have Money Will Travel, But Where?

In choosing destination countries, transnational millionaires tend to consider a country’s quality of life, political and economic stability, financial incentives such as preferential tax treatment, and favorable immigration policies. Programs offering residence and citizenship to people who invest a large amount of money (sometimes known as “golden visas” or “golden passport” programs), so-called “digital nomad” policies, and other efforts by destination countries have helped shape choices. An estimated 30 percent of wealthy migrants enter their new countries via investment migration programs. Many more wealthy people will acquire residence in a new country but never personally migrate there, instead using the status purely for tax or other benefits.

Patterns of wealthy migration have changed, due to shifting geopolitical trends. Wealthy migrants have typically been most attracted to countries with secure sociopolitical environments, which in the past has included the United States, Canada, Germany, Australia, and the United Kingdom. Recently, the international elite seem to be opting for more stable economies, firstly in the United Arab Emirates, which was projected to be the top destination for migrant millionaires globally in 2022, followed by Australia, Singapore, Israel, and Switzerland. This is partly a reflection of the onward movement of growing numbers of Russian nationals who might face sanctions or political pressure in the West.

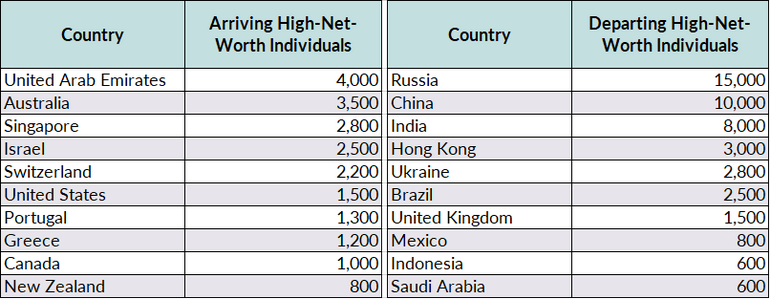

Table 1. Top Countries for Arriving and Departing High-Net-Worth Individuals, 2022

Notes: High-net-worth individuals are people with wealth of U.S. $1 million or more. Data are projections and refer to individuals expected to have relocated and remained in their new country for at least six months.

Source: Henley and Partners, “Henley Private Wealth Migration Dashboard,” accessed November 3, 2022, available online.

Transnational Millionaires in Global Cities

While wealthy individuals have long moved from one country to another, recently rising numbers are due to a combination of factors. For one, the number of millionaires has been increasing; estimates vary widely depending on methodology, but Credit Suisse has estimated that there were 62.5 million millionaires worldwide as of the end of 2021, a number projected to grow to 87.6 million by 2026. Global political and economic turbulence is another factor, and the effects of climate change could increase as a driver. So too is the growing presence of investor migration policies offering an easy path to residence or citizenship.

Purchasing land and other property often provides a safe deposit for high-net-worth migrants to store their savings, especially in global cities with stable politics and currency. Singapore, for instance, has long been a favored destination for investors from mainland China, while London has been so popular with elite Russians that the city is sometimes pejoratively referred to as Londongrad. These global cities act as hubs for information and capital that transcend national borders. They also typically offer high living standards, good schools, and robust transportation linkages.

Tax havens such as the Cayman Islands, Monaco, and Switzerland have also traditionally attracted the transnational wealthy. Some countries, such as those in Southern Europe, have generally sought to boost immigration in the face of aging populations, and have taken steps to offer preferential tax regimes and other policies targeting wealthy migrants.

The recent interest in the United Arab Emirates, particularly its major cities Abu Dhabi and Dubai, encapsulates several of these trends: The country has zero income tax, is centrally located at the nexus of three continents, has positioned itself as a cosmopolitan hotspot, and offers a vibrant economy due to booming oil and gas revenue. Meanwhile, the emirates sit largely outside the Western political sphere, offering peace of mind to wealthy Russians and others who might run afoul of sanctions or possible criminal indictments elsewhere.

Among those who have recently bought houses and parked yachts in the United Arab Emirates are oligarchs with close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin, reportedly including Roman Abramovich, the billionaire former owner of the Chelsea soccer club whose private jet was grounded in Dubai for months. The emirates have long been a hotspot for tourists from Russia, with Russian ice cream brands and other treats available in beachside commercial strips. But international crackdowns following the invasion of Ukraine seem to have accelerated this trend.

The pandemic appears to have been another factor in the growing attractiveness of destinations such as the United Arab Emirates and Israel. Particularly compared to East Asia, many Middle Eastern countries were laxer about travel restrictions, while also boasting high rates of vaccination and robust public-health infrastructure. During the pandemic, wealthy migrants particularly from mainland China and Hong Kong sought to escape harsh travel bans by securing legal residence elsewhere.

In Europe, the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union and resultant economic turbulence was a factor in that country’s relative declining popularity for millionaire migrants. London also has imposed new taxes on arrivals in recent years.

Welcome or Not?

Not everyone in destination countries is convinced about the benefits of an influx of new wealthy, foreign-born neighbors. The arrival of these well-heeled newcomers has at times prompted concerns about exacerbating income inequality and unaffordability. In response, governments have differed in their policy approaches. Immigration policies toward the transnational elite vary in their permitted duration of stay, allotted freedoms, and preferences for migrants by nationality. At times, restrictions have fallen to local jurisdictions.

Housing and the Foreign Buyers’ Tax

Investment in real estate is popular for migrants seeking investment-based residency and tends to have some local benefits. Developers, builders, and others earn revenue from increased housing demands. Yet countries fear potential housing booms and busts caused by transnational investment in real estate, which has the potential to price out low- and middle-income natives, particularly if new home buyers are only living there part-time. As the pandemic subsides, the costs of energy and other daily necessities have dramatically increased, prompting concerns that native-born residents are undergoing a cost-of-living crisis while wealthy immigrants are further stretching housing prices.

These fears have foundations in the long-term lack of housing supply in many destination countries. The United States, for instance, is approximately 3.8 million homes short of meeting housing needs, due in large part to lack of new homebuilding, according to Up for Growth. Many central banks have attempted to mitigate inflation by increasing interest rates, with the hopes of tamping down runaway costs of living. U.S. average 30-year fixed-rate mortgages hit more than 7 percent in October, the highest in two decades, while borrowers in countries where variable-rate mortgages predominate stand to see their monthly payments shoot up. Yet this policy maneuver may do little to discourage transnational millionaires who are able to buy in cash and stand poised to benefit from lower housing prices as hot markets cool.

At times, this situation can drive negative perceptions and anti-immigrant sentiment, particularly if wealthy arrivals tend to be of a minority racial or ethnic group or the community is undergoing demographic change. In Vancouver, which has a large and thriving immigrant community from Asia, anti-Asian racism escalated as the pandemic spread beyond China. Anti-Asian hate crimes in Vancouver grew eightfold between 2019 and 2020 and were the highest in North America. Violence also increased in San Francisco, Seattle, and other cities that have large Asian immigrant populations. While the violence was driven by many factors, a through-current has been a lack of affordable housing and disparities between a small number of wealthy migrants and less well-to-do long-term residents.

In response, a popular policy for many jurisdictions has been a foreign buyers’ tax, which imposes a special surcharge for noncitizens or immigrants without permanent residence. British Columbia, the province including Vancouver, imposed such a tax in 2016, and recently Ontario, which includes Toronto, enacted a provincewide Non-Resident Speculation Tax. This year, Canada’s national government also announced a temporary two-year ban on foreign investors buying homes across the country. Singapore recently raised taxes for immigrants without permanent residence looking to buy residential property, from 20 percent to 30 percent. In the United States, a 30 percent tax on profits of foreign real-estate investors has been in effect since the 1980s.

Yet despite its popularity as a policy response, the foreign buyers’ tax has not been proven to significantly quell prices. While the tax is popular because it does not affect domestic buyers, research suggests it has little effect on the market, in part because foreign buyers often work with local residents or citizens to buy property. Rather, the increase of housing supply is more crucial.

“Birth Tourism”

Another concern for destination countries is the short-term migration of pregnant women intending to give birth there in order for their child to gain citizenship. The practice is only a matter of concern in countries that grant birthright citizenship, such Brazil, Canada, and the United States. Because of the costs inherent in such a journey, most pregnant travelers tend to be economically well off. Citizenship is not the sole factor for giving birth in a different country; Russian and Eastern European birth tourism to Brazil, for instance, has grown due to inadequate obstetric care and high rates of medical malpractice in their native countries.

The governments of destination countries have at times sought to limit this practice, which critics sometimes denounce as “chain migration” or the more pejorative “anchor babies.” In early 2020, the Trump administration put forth a rule preventing pregnant travelers on temporary visas from entering the United States. Similar proposals have been proposed in Canada but never enacted. Australia previously granted citizenship to any child born on its territory, but enacted restrictions in 1986 following controversy over a Tongan citizen who gave birth in the country.

The Lure of Foreign Money

Frequently, governments view wealthy immigrants as opportunities to inject cash into their local economies. The potential for a lucrative tax windfall is an obvious factor. But even places with no or limited taxes see affluent migrants as customers for local restaurants, banks, and other companies. Money aside, many leaders also view an influx of wealthy residents as a barometer of their success in creating attractive, booming societies.

In line with this thinking, then-New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg—himself a multibillionaire—said in 2013 that it would be a “godsend” if all the world’s billionaires would move to his city: “They are the ones that pay a lot of the taxes. They’re the ones that spend a lot of money in the stores and restaurants and create a big chunk of our economy.” These kinds of arguments have been particularly appealing for countries such as Monaco, the United Arab Emirates, and others with relatively small populations and which view their futures as hinging on becoming stable financial hubs.

Yet in some contexts, transnational millionaires remain in an “expat bubble” that floats above host communities in a segregated, self-contained society of fellow wealthy migrants. Because of the rapid pace of globalization and the ease of moving goods internationally, millionaire migrants may continue to primarily speak the language of their country of origin, experience the same media, and communicate with the same networks. Particularly for countries with strong ethnic and national identities, this can stir tensions between native- and foreign-born communities.

Tax and Visa Programs

In courting transnational millionaires, many countries provide tax incentives, visas for migrants earning incomes above a certain threshold, and other benefits. Portugal, for instance, offers a Non-Habitual Residents tax program which includes multiple exemptions and other benefits for foreign nationals who earn a significant share of their income abroad. Singapore, meanwhile, has long been regarded as a tax haven with low rates and special exemptions for start-up companies, and last year, the Philippines enacted a law modeled after the city-state’s, in an attempt to attract foreign money.

Additionally, digital nomad programs are a growing phenomenon catering to affluent professionals. Policies that allow employees to work remotely from abroad accelerated following the onset of the pandemic, as more white-collar workplaces abandoned requirements for employees to come to the office. As of June, more than 25 countries and territories had some sort of program for international freelancers, self-employed people, and other remote workers. Visas last from a few weeks to several years, tend not to authorize local work, and require varying levels of monthly income.

Historically, two common policies targeted towards affluent migrants have allowed them to secure residence and citizenship through making an investment, such as by purchasing a house. More than 40 countries offered residence-by-investment programs as of this writing, with the number growing in recent years. However, these kinds of schemes have attracted new scrutiny amid allegations of corruption and following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This year, EU Member States Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Malta scaled back their investment-based citizenship programs amid EU opposition.

The schemes differ in length and only some provide a path to citizenship. For instance, in Portugal, purchasing property worth at least 350,000 euros in certain regions, starting a business that creates at least ten new jobs, or transferring at least 1.5 million euros into a Portuguese bank allows someone to become an EU resident, which grants visa-free access to the entire European free-movement area and puts them on a path to citizenship. The Cayman Islands has a program allowing applicants to invest $2.4 million in real estate to gain permanent residence and potentially citizenship. More robust citizenship by investment programs such as Turkey’s, meanwhile, offer a much quicker path to obtaining a new passport in just a few months.

Mixed Impacts for Origin Countries

For origin countries, the departure of wealthy nationals can deprive state coffers of tax money and other opportunities while contributing to a brain drain (or at least the perception of one). China for instance has aimed to clamp down on emigration as it continues a zero-COVID strategy that has sharply reduced mobility; authorities have sought to limit passport renewals, make it for difficult for applicants to secure documents necessary for international visas, and prevent people from storing large amounts of money overseas.

Affluent emigrants, however, can create a broad diaspora network with ties between their old and new countries. Emigration can be a powerful way to boost development in origin countries, through the sending of money and other remittances. Most remittances come from high-income countries, with the United States the top sending country and the origin for nearly $74.6 billion in formal transfers in 2021, according to the World Bank. Other top countries for remittances were Saudi Arabia ($40.7 billion), China ($22.9 billion), Russia ($16.8 billion), and Luxembourg ($15.6 billion). Remittances far exceed foreign direct investment and development aid in developing countries and tend to increase aggregate demand and gross domestic product (GDP). However, countries that receive remittances may also experience declines in manufacturing and exports.

The Future of Millionaire Migration

Migration trends of the wealthy are constantly evolving. Uncertainty due to global security, political upheaval, living standard concerns, or environmental change can drive migration of transnational millionaires, who hope to secure their legacies, wealth, and lifestyles in stable destinations. Residence and citizenship programs in destinations help propel these trends, as do signs of socioeconomic stability, global status, and existing migrant networks.

Governments have at times taken different approaches toward transnational millionaires, which may have blunted the impact of wealth migration to varying extents. While accounting for a tiny share of the world’s 281 million international migrants, millionaires and other wealthy individuals play an outsized role and have at times loomed large in debates. The subsiding of the global pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have prompted a new wave of affluent people looking to move across borders, but recent history has shown that these migrants have been on the move for years in increasing numbers. As trends evolve, so too will policies targeting millionaire migrants, as governments and communities reckon with the promises and perils of new outside wealth.

Sources

AfrAsia Bank. 2020. Global Wealth Migration Review 2020. Port Louis, Mauritius: AfrAsia Bank. Available online.

Ahir, Hites, Heedon Kang, and Prakash Loungani. 2014. Seven Questions on the Global Housing Markets. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Available online.

Bartenstein, Ben, Nicolas Parasie, and Archana Narayanan. 2022. Abramovich’s Dubai House Hunt Shows Russian Diaspora Widening. Bloomberg News, March 25, 2022. Available online.

Bloomberg News. 2022. Rich Chinese Worth $48 Billion Want to Leave — But Will Xi Let Them? Bloomberg News, July 18, 2022. Available online.

Cooban, Anna. 2022. Russia Is ‘Hemorrhaging’ Millionaires. CNN, June 14, 2022. Available online.

Deschamps, Tara. 2022. Ontario Foreign Buyers Tax Hike Won’t Have Much Effect on Already Cooling Market: Experts. The Canadian Press, October 25, 2022. Available online.

Folha de S.Paulo. 2022. Childbirth Tourism Brings Russian Women to Brazil in Search of Citizenship for Their Children. Folha de S.Paulo, April 11, 2022. Available online.

Frank, Robert. 2017. For Millionaire Immigrants, a Global Welcome Mat. The New York Times, February 25, 2017. Available online.

Glenny, Misha. N.d. The Geopolitics of Wealth Migration. Henley and Partners. Accessed November 3, 2022. Available online.

Griffith, Andrew. 2021. Birth Tourism in Canada Dropped Sharply Once the Pandemic Began. Policy Options, December 16, 2021. Available online.

Harpaz, Yossi. 2022. Democratic Decline Drives Millionaire Migration. Henley and Partners blog post, August 12, 2022 Available online.

Henley and Partners. N.d. Henley Private Wealth Migration Dashboard. Accessed November 3, 2022. Available online.

Hooper, Kate and Meghan Benton. 2022. The Future of Remote Work: Digital Nomads and the Implications for Immigration Systems. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

KNOMAD/World Bank. 2021. Outward Remittances. Updated November 2021. Available online.

Pearson, Natalie Obiko. 2021. This Is the Anti-Asian Hate Crime Capital of North America. Bloomberg News, May 7, 2021. Available online.

Reuters. 2021. Singapore Tightens Curbs to Cool Buoyant Property Market. Reuters, December 15, 2021. Available online.

Saul, Michael Howard. 2013. Mayor Bloomberg Wants Every Billionaire on Earth to Live in New York City. The Wall Street Journal, September 20, 2013. Available online.

Shorrocks, Anthony, James Davies, and Rodrigo Lluberas. 2022. Global Wealth Report 2022. Zurich: Credit Suisse Research Institute. Available online.

Steffen, Juerg. N.d. The Changing Face of Millionaire Migration. Henley and Partners. Accessed November 3, 2022. Available online.

Tomlinson, Peta. 2022. Where Are Millionaires Moving to in 2022? High Net Worth Individuals Are Leaving the US, Britain, China and India for the UAE, Australia and Singapore – but Why? South China Morning Post, August 3, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Which Are the Best Countries Offering Citizenship by Investment? 40 Nations – from Thailand to the UAE – Offer ‘Golden Visas’ to High Net Worth Individuals Splurging Millions on Property. South China Morning Post, July 19, 2022. Available online.

Up for Growth. 2022. 2022 Housing Underproduction in the U.S. Washington, DC: Up for Growth. Available online.