You are here

COVID-19 Pandemic Ushered in Unprecedented Slowdown of Asylum Claims

Rohingya children in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. (Photo: Christian Enders/Jesuit Refugee Service)

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an extraordinary slowdown in global movement, as border closures, travel restrictions, and suspension of government services created obstacles for migrants and travellers across the planet, including 31 million refugees and asylum seekers. Many people newly displaced by war or other factors have faced difficulties formally requesting asylum in a new country, which is often the first step to securing international protection.

Globally, 1.1 million people sought asylum in 2020, the most recent full year for which data are available. This amounted to a 45 percent drop from the 2 million asylum claims filed in 2019, the largest single-year decline since current recordkeeping began in 2000. Numbers ticked up slightly in the first half of 2021, as international travel and migration showed some signs of reviving, but were still 36 percent below pre-pandemic levels, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Border closures were a major factor in this development. But even people who had managed to reach another country in search of protection faced challenges registering their presence or renewing their application for asylum. This is a crucial step, because whatever their ultimate fate—whether to be resettled to a third country, remain in their place of first asylum, or return to their native country—people typically must first formally request asylum and have their claim evaluated through a process often known as refugee status determination. Otherwise, they may wind up in irregular status, be unable to access social services, and risk prosecution, detention, and deportation.

As offices closed and many services were offered only remotely during the pandemic’s first year, asylum seekers faced a range of bureaucratic hurdles that slowed processing. Even as the number of asylum applicants fell, slow processing times contributed to a growing backlog. Worldwide, 4.4 million individual asylum applications remained pending as of July 2021, a 7 percent increase from just six months prior. Not only do backlogs mean asylum seekers might wait in limbo for multiple years, they can also clog up administrative processes, making it harder to remove ineligible applicants and undermine faith in the asylum system as a whole.

This article examines the challenges to asylum processing during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly for UNHCR. The global public-health crisis was in many ways unprecedented and impossible to prepare for. While asylum systems adapted over the course of the pandemic, they did so unevenly and at times created new challenges for applicants.

Refugee Status Determination

Refugee status determination is the process by which national governments or the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) evaluate individuals or groups to determine if they qualify for international protection. Countries may have their own particular legal definitions for the terms, but for the purposes of this article an individual who has sought protection and whose application is still being processing is an asylum seeker; those whose applications have been approved are refugees. Not every asylum seeker becomes a refugee, but every refugee was once an asylum seeker.

UNHCR bases its determinations for refugee status on the 1951 Refugee Convention, which offers protection to people fleeing their country of origin because of a well-founded fear that they will face persecution due to their race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

How the United Nations Processes Asylum Seekers

While many people might think that most refugees live in Europe or North America, in fact 73 percent are hosted in countries neighboring their place of origin, and only a tiny fraction will be resettled elsewhere. When they first arrive in a new country, forced migrants often go through asylum processing, through which authorities identify why they fled their country of origin and assess the risks they may face if returned. This processing is an integral part of the international protection regime, allowing for documentation of possible human-rights violations people may have suffered and paving the way for governments or the United Nations to protect them and provide specialized assistance such as access to housing, health care, psychosocial support, and education.

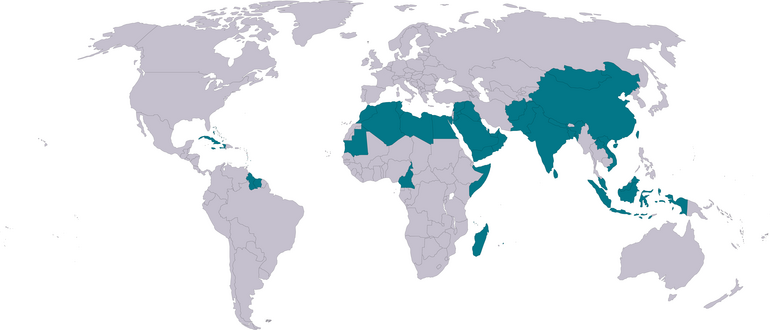

In most countries, asylum determination is undertaken by government authorities, and processes vary widely. But 51 countries do not conduct this process on their own, and instead have delegated it to UNHCR. These countries are located mostly in Africa, the Americas, and Asia (see Figure 1). In most years less than 15 percent of all asylum applications are made solely to UNHCR, but this nonetheless adds up to a sizable amount; in 2015, the agency received a recent high of 269,000 applications.

Figure 1. Countries in Which UNHCR Is Solely Responsible for Refugee Status Determination, 2021

Source: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), UNHCR Refugee Status Determination Map - August 2021 (Geneva: UNHCR, 2021), available online.

UNHCR’s role in the countries where it undertakes status determination is essential, as it often offers the only available legal identity documents and protection to humanitarian migrants. The process can differ by country, but typically an individual first registers with the agency either in person or by phone, and may receive documentation to prove that they have done so. Even before a decision is made to grant or deny refugee status in an individual case, simply being registered with UNHCR transforms an asylum seeker into a “person of concern” under the agency’s mandate, which typically protects them from being detained and deported by authorities. It also allows them to access services provided or facilitated by UNHCR, other international organizations, and local implementing partners, such as schools and hospitals, which are often crucial for applicants’ day-to-day lives.

Once individuals file an application with UNHCR, they undergo interviews with agency officials who determine whether they meet the international legal definition for refugee status, which hinges on whether they are likely to face persecution upon return to their country of origin. These interviews are vitally important, and in many cases form the only evidence in support of the applicant’s claim for asylum. In some contexts, UNHCR undertakes this process for each individual who registers with them, but in others it conducts an abbreviated procedure for groups.

To guide the process, UNHCR relies on its published guidelines to maintain global standards and safeguard applicants’ rights. These are updated regularly to clarify the rules of refugee status determination, set down core principles, and establish standard timelines and processes.

Effects of COVID-19 on Asylum Processing

At the beginning of the pandemic, UNHCR published recommendations for states to continue their processes for determining refugee status, even if it meant adopting some modified procedures such as recording less detailed data and conducting interviews remotely. Not continuing to process applications, it warned, could leave thousands without any form of protection. In subsequent months, the agency reinforced its directives on remote interviewing, which it claimed helped avoid creating a massive backlog or lengthy waits for applicants. Since August 2020, UNHCR’s formal guidelines have incorporated standards for status determination conducted through remote means, including the right to have legal representation and translators.

The pandemic resulted in a drastic increase in needs for many asylum seekers and refugees, as unemployment in many host countries accelerated, incidents of domestic violence reportedly increased, and access to health care and other services was at times limited. Meanwhile, leading public figures in multiple countries scapegoated asylum seekers and other migrants as carriers of disease or competitors for jobs, leading to social stigma and occasionally aggressive immigration enforcement at the same time that UNHCR and other agencies were forced to restructure their work, reassess their priorities, and suspend some operations. For example, in India, where the authors work as legal representatives on behalf of refugees and asylum seekers, police conducted raids and mass arrests of foreign-born Rohingya who lacked or had out-of-date documentation, which might have been due to lockdowns and difficulty they faced securing documents during the pandemic (responsibility for refugees in India is split between UNHCR and the national government, depending on the individual’s origin). Meanwhile, foreign-born members of other groups, such as Afghans and Chin, were being deprioritized during those months due to UNHCR’s lack of capacity. Similarly, in Egypt, UNHCR adjustments made it easier for registered asylum seekers already in the country to renew their documentation, but the situation nonetheless contributed to a backlog that was not cleared until early 2022.

The extent of the pandemic’s impact on UNHCR operations is unclear, but many refugee status determination operations across Asia came to a complete halt in early 2020 and, as of March 2022, many offices had yet to return to normal. The reliance on remote work has been neither easy nor fast, leading to delays at all levels of the process; many interviews continue to be slower, longer, and fewer in number. In normal times, asylum seekers may secure legal representation, giving them access to legal counsel, help filling out forms, a presence during their interview, and advocacy on their behalf with UNHCR and its partner organizations. However, these legal representatives could be of little help when UNHCR suspended operations.

Combined, these and other factors led to a 59 percent decrease in the number of new applications filed with UNHCR in 2020, to just 49,000. Applications for protection dropped across the board, due to travel restrictions and other factors, but the decline in applications made via national asylum procedures and via joint UNHCR/national government procedures was less severe than those made through UNHCR systems (44 percent and 58 percent, respectively).

Figure 2. Number of Asylum Applications Registered Globally by Authority Responsible, 2010-20

Note: Figure represents the number of new and appeal applications.

Sources: UNHCR, Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2019 (Copenhagen: UNHCR Statistics and Demographic Section, 2020), available online; UNHCR, Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2020 (Copenhagen: UNHCR Statistics and Demographic Section, 2021), available online.

Still, good practices from many UNHCR operations emerged in the midst of these challenges. Among these were registration through phone or online platforms, which allowed individuals to lodge asylum claims even when they could not meet in person due to health concerns or government regulations. Further, once interviews resumed, some legal representatives reported success participating remotely. As travel restrictions eased and offices reopened over the first six months of 2021, the number of new applications to UNHCR was nearly one-third higher than over the same period in 2020, whereas the total number of new applications in countries where governments were responsible for refugee status determination dropped slightly (this rebound was also a reflection of the sharp dropoff in UNHCR processing in 2020). Some of these new mechanisms can reasonably be expected to continue in the post-pandemic world, supplementing face-to-face procedures and thereby expanding access to would-be applicants who previously might have encountered restrictions on movement, financial constraints, or other challenges.

In South and Southeast Asia, New Crises Add to Pandemic Challenges

The pandemic was accompanied by fresh upheavals in Afghanistan and Myanmar, which have long been major refugee-origin countries. In Myanmar, a coup in early 2021 resurrected an authoritarian and violent military leadership, whereas in Afghanistan later that year the Taliban returned to power once U.S. and other international forces withdrew. These events have resulted in large numbers of people fleeing and discouraged many previously displaced refugees and asylum seekers from returning. Nearly 2.1 million registered Afghan refugees lived in Pakistan, Iran, and other countries as of May, more than 175,000 of whom arrived since January 2021. An estimated 53,000 people fled Myanmar since early 2021, joining the almost 1 million Rohingya refugees and asylum seekers already in neighboring countries. These numbers may grow in coming months and years, as pandemic-related barriers to international movement recede, particularly along Afghanistan’s land borders, and as situations in the countries become increasingly desperate. Economic crisis and a severe drought in Afghanistan, for instance, have pushed millions of people into threat of famine, while conflict in multiple parts of Myanmar has persisted.

The effects of these conflicts were compounded by the complications created by the pandemic. In India, which is host to both Afghan and Burmese refugees, asylum processing interviews were completely suspended between March and August 2020, and afterwards were few and far between. This resulted in myriad delays; whereas UNHCR’s guidelines state that first-time applications should receive a determination within a year of registration, waits instead have extended up to four years. Successive pandemic waves have not helped; UNHCR as of this writing had not yet resumed work in person, and strict lockdowns in early 2021 prevented many would-be asylum seekers from Myanmar from registering. Meanwhile, the Taliban’s return to power prompted a wave of new requests from Afghan asylum seekers to register with UNHCR, schedule an interview, or appeal their previously rejected case. Delays have caused frustration among asylum seekers, as made clear by demonstrations conducted by displaced Afghans and others in front of UNHCR’s New Delhi office in August 2021.

Asylum seekers have felt the lack of access to UNHCR and its partners acutely. Even while remote operations have allowed for some processing to continue, the lack of in-person services has prompted significant frustration. In South and Southeast Asian countries where UNHCR is responsible for many refugees’ protection, not being able to visit the agency’s offices has meant that there is no human face to the interactions and eroded asylum seekers’ trust in the system. An Afghan asylum seeker whose husband died during the pandemic told the authors that, as a single mother, she could no longer return to Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, but UNHCR had not responded to her queries requesting her case be reopened due to the significant changes in her circumstances and her native country. Many others have reported that helplines put in place during the pandemic were often unreachable or failed to provide clear answers for when interviews would be conducted and when cases would be resolved. As of this writing, UNHCR was working on cases filed in 2019, while those who registered more recently have been repeatedly rescheduled.

Many National Asylum Systems Made Their Own Adjustments

Among national asylum systems, 95 percent adapted at least some procedures in response to the pandemic by the end of 2020, although results varied. Germany, for instance, hosts the fifth-most refugees in the world, and in spring 2020 its Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) made it possible for individuals to apply for asylum in writing, as opposed to in person. This ensured people could still apply for asylum and remain in Germany while their application was being processed. In-person interviews resumed by the end of 2020, with social distancing and other safety measures in place. BAMF also reduced delivery of rejections, only formally denying asylum when applicants had access to legal advice. Likely at least partly because of these modifications, Germany was one of the few countries to reduce its backlog of asylum applications in 2020, which it did by slightly more than one-fifth.

On the other hand, in the United Kingdom, the number of asylum applicants awaiting a decision had doubled since the start of 2020, to more than 85,000 as of March. The number of asylum applications and initial decisions fell sharply at the beginning of the pandemic and as subsequent restrictions hit. All substantive asylum interviews were suspended in March 2020, but by that November were resumed across the country. However, applications subsequently ticked up, and the nearly 49,000 new asylum claims in 2021 were a 63 percent increase over 2020.

Turkey, the single largest refugee-hosting country globally, took on sole responsibility for refugee status determination in 2018, before which it had conducted the process in tandem with UNHCR. The number of applications for international protection declined by 44 percent in 2020, to slightly more than 31,000, as nearly all asylum-related activities were suspended for several months, including a closure of registration offices across the country. When processing did resume, researchers reported that asylum seekers faced challenges securing consistently high-quality interviews, having their evidence appropriately assessed, and obtaining an interpreter and legal assistance, among other issues. All of this resulted in extreme hardship for many people seeking international protection.

Return to Normal?

The last two years have served as a reminder that asylum seekers and refugees remain incredibly vulnerable. Not only have they dealt with the pandemic’s impact on their jobs, health, and societies, but they have done so while navigating processing systems that were adapting to new circumstances and struggling to innovate. While it is unrealistic to imagine asylum systems could have withstood the generation-defining pandemic without any challenges, proactive steps by UNHCR and governments could have made it easier for more people to access protection during this unprecedented moment. Border restrictions, closed offices, and other consequences of the pandemic certainly exacted a toll over the last two years, but COVID-19 only exacerbated underlying problems in humanitarian processing given the already long queues of pending asylum applications.

As the world limps back to normalcy, many national asylum systems have been quick to resume full activities. UNHCR has in many cases been slower, however, even as the need for protection is greater than ever before. New variants and repeated COVID-19 waves have complicated the situation for countless migrants, and situations such as those in Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Ukraine appear slated to produce more refugees in coming months. Procedural standards are necessary to ensure at-risk people can access the protection to which they are eligible, and legal representatives’ full participation can help asylum seekers navigate further delays. Going forward, officials might also consider how strategies such as remote interviews might complement their in-person services to expand access to protection, while continuing to build trust in the system. The pandemic was an exceptional moment in history, but it may also prompt needed reflection on the challenges that have long plagued the global asylum system.

Sources

Euronews. 2021. Afghan Refugees in India’s New Delhi Demand Rights Outside UNHCR. Euronews, August 23, 2021. Available online.

European Asylum Support Office (EASO). 2021. EASO Asylum Report 2021: Annual Report on the Situation of Asylum in the European Union. Valletta, Malta: EASO. Available online.

European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE). 2021. Country Report: Turkey, 2020 Update. Brussels: ECRE. Available online.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). N.d. Contribution by Germany to the Questionnaire on the Impact of COVID-19 on the Human Rights of Migrants. N.p.: OHCHR. Available online.

Refugee Council. 2022. Changes to Asylum & Resettlement Policy and Practice in Response to Covid-19. Last updated January 28, 2022. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2020. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2019. Copenhagen: UNHCR Statistics and Demographic Section. Available online.

---. 2020. Practical Recommendations and Good Practice to Address Protection Concerns in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Brussels: UNHCR Regional Bureau for Europe. Available online.

---. 2020. Remote Interviewing: Practical Considerations for States in Europe. Brussels: UNHCR Regional Bureau for Europe. Available online.

---. 2021. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2020. Copenhagen: UNHCR Statistics and Demographic Section. Available online.

---. 2021. Mid-Year Trends 2021. Copenhagen: UNHCR Statistics and Demographic Section. Available online.

---. 2021. UNHCR Refugee Status Determination Map - August 2021. Geneva: UNHCR. Available online.

---. 2022. Myanmar—Operational Update. Yangon, Myanmar: UNHCR. Available online.

---. 2022. Update on UNHCR’s operations in the Middle East and North Africa. Geneva: UNHCR Executive Committee of the High Commissioner’s Programme. Available online.

---. N.d. Afghanistan Emergency. Accessed May 4, 2022. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, United Kingdom. N.d. Asylum in the UK. Accessed May 4, 2022. Available online.

UK Home Office. 2020. Statistics Relating to COVID-19 and the Immigration System, May 2020: Official Statistics. London: UK Home Office. Available online.

Tong, Katie. 2021. UNHCR Country Strategy Evaluation: Egypt. Geneva: UNHCR. Available online.

Trendall, Sam. 2022. UK’s Asylum Backlog Has Doubled Since 2020 – and Home Office Cannot Say How Many Interviews It Conducted Last Year. Public Technology, March 4, 2022. Available online.