The People Perceived as a Threat to Security: Arab Americans Since September 11

Since the terrorist acts of September 11, 2001, Arab Americans have regularly been featured in the press as a group "of interest" to many federal agencies, particularly the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Yet government security agencies have recruited them for their language skills — the FBI has hired 195 Arabic linguists since 9/11 although other agencies, such as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), have not released the number of new hires. Despite demand, the number of recruits is low due to bureaucratic problems and the difficulties Arab Americans face in getting top-level security clearances. Similar to other U.S. immigrant groups in the past, they are viewed as suspect simply because of their origin.

Although the term "Arab American" is often used, it remains misunderstood. Who exactly is an Arab American? Are all Arab Americans Muslim? Has the immigration rate of Arab Americans decreased as a result of 9/11? What has been the net fall-out effect of 9/11 on this group? This article will provide definitions, look at flow data from recent years, and examine the trend of immigration and security policies affecting Arab Americans.

Definitions

Arab Americans are the immigrants (and their descendents) from the Arabic-speaking countries of the Middle East and North Africa. Under this classification, Arabic-speaking countries include the members of the Arab League and range from Morocco in the west to Iraq in the east (see sidebar). Individuals from Iran and Turkey, where the predominant languages are Farsi and Turkish, respectively, are not considered to be of Arab origin even though these countries are part of the Middle East.

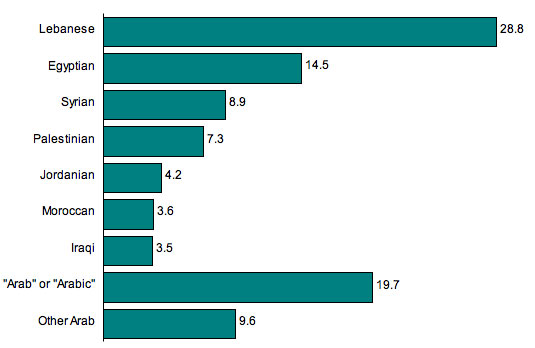

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Arab Americans are those who responded to the 2000 census question about ancestry by listing a predominantly Arabic-speaking country or part of the world as their place of origin. The main Arab-speaking countries cited in the 2000 census included Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, and Syria.

Although some people from Arabic-speaking countries identify themselves as Arab, many do not but are regularly defined as such in the United States by the government and the average American, adding further weight to the term. Because some choose a national identity, such as Lebanese or Egyptian, over the term Arab, the diversity of the community must be recognized at the outset of any discussion about Arab Americans. In truth, there are hot debates about whether there is one or many communities of Arab Americans because of the distance, both physical and emotional, between various groups.

|

|

||

|

In regards to religious affiliation among Arab Americans, surprisingly few studies have been done. However, the Arab American Institute, based on a 2002 Zogby International poll, estimates that 63 percent of Arab Americans are Christian, 24 percent are Muslim, and 13 percent belong to another religion or have no religious affiliation. The Muslim Arab-American population includes Sunni, Shi'a, and Druze. Among the Christians, 35 percent are Catholics (Maronites, Melkites, and Eastern Rite Catholics), 18 percent are Eastern Orthodox (Antiochian, Syrian, Greek, and Coptic Christians), and 10 percent are Protestant.

The high proportion of Christians among Arab Americans is partially due to the descendants of Arab immigrants who arrived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; they mostly came from Mount Lebanon, an area inhabited by Maronite Christians and Druze that is now in Lebanon. Also, minority groups — Maronites and Orthodox Christians from Lebanon, Coptic Christians from Egypt, Shia' Muslims and Chaldeans from Iraq, and Orthodox Christians from Palestine — are immigrating to the United States today in larger numbers than the majority Sunni Muslim population of the Middle East.

How Arab Americans Are Counted

Unlike Asian, white, or black, "Arab" is not a racial category for the Census Bureau. Rather, Arab Americans are considered white, defined by the Census Bureau as "a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa." This distinction dates back to court decisions from 1913 to 1917 on the "whiteness" of Syrian and Palestinian immigrants.

Arab Americans who received only the short form of the 2000 census, which is sent to all U.S. households, could check the "white" box for race; if they self-identified as "other" and then identified themselves on the long form as a person from the Middle East or North Africa, the Census Bureau reassigned them to the "white" category. This classification system is in line with other federal guidelines on race and ethnic standards, as set out by Directive 15 by the Office of Management and Budget, and therefore is present in many administrative forms.

Since the 2000 census, the Census Bureau has published two reports on Arab Americans, both of which are based on the long form that asks about ancestry and is sent to only one-sixth of all U.S. households. The first report, issued in 2003, reported that about 1.2 million people in the United States reported Arab ancestry alone or in combination with another ancestry. The second report, issued in 2005, focused on the 850,000 people who reported at least one Arab ancestry and no non-Arab ancestries (see Table 1 and Figure 1). Therefore, a person of British-Egyptian heritage would have been included in the first report and excluded from the second.

|

|

||

|

In both reports, the Census Bureau differs from the Arab League membership definition in that it excludes those from Mauritania, Somalia, Djibouti, Sudan, and the Comoros — countries that are members of the Arab League and include large Arabic-speaking populations. Arab-American organizations estimate that the Census Bureau counted only one of every three Arab Americans in 2000, and therefore these organizations estimate the number at approximately 3.5 million, or 1.2 percent of the total U.S. population. This 3.5 million estimate of Arab Americans in 2000 also includes those of mixed Arab and non-Arab heritage, unlike the 2005 Census report.

Another way to examine the Arab-American population is to look at the foreign-born population from Arab countries. Although the media portray the Arab-American population as wholly foreign born, the 2005 census report found that only about 50 percent of Arabs in the United States were foreign born; of these, about half were naturalized U.S. citizens and the other half were not citizens. Therefore, half of the Arab Americans in 2005 report were either born in the United States or born abroad to U.S.-citizen parents. Of the foreign born, 46 percent arrived between 1990 and 2000, compared to 42 percent of the total foreign-born population.

Immigrant and Nonimmigrant Flows Since 9/11

Many assume that the immigration of Arabs to the United States decreased after 9/11. However, the numbers of those admitted as immigrants or those who became legal permanent residents from Arabic-speaking countries has remained level at around four percent of the total number of foreign nationals admitted as immigrants to the United States, even though there was a drop in 2003. In 2005, over 4,000 nationals from Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Morocco, Somalia, and Sudan, in addition to an unknown number of Palestinians, became permanent residents (see Table 2).

What has dropped drastically post-9/11 is the number of nonimmigrants who are issued visas and admitted to the United States as tourists, students, or temporary workers. The largest numerical drop between 2000 and 2004 (70 percent) has been in the number of tourist and business visas issued to individuals from Gulf countries, which include Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, and Oman.

Although there was a decrease in the number of all incoming foreign students between 2001 and 2004, the number of student visas issued to individuals from Arabic-speaking countries dropped substantially. The greatest numerical drop, from 19,696 student visas in 2000 to 6,826 in 2004 (65.3 percent), came from the Gulf countries. The number of Egyptians who entered on student visas dropped 52.7 percent between 2000 and 2004 (see Table 3).

One of the first reasons cited for the decrease in the number of foreign students was increased security measures, particularly the Patriot Act and its provision that required the implementation of the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS). SEVIS is an online database that monitors international student compliance with immigration laws by requiring all schools to be certified and to regularly update information on each foreign student, including their visa type, status as a student (full-time enrollment is required), biographical information, class registration, and current address.

Recent reports by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the Institute of International Education (IIE) found that the decline in the number of international students is not due to SEVIS but, according to IIE, to "real and perceived difficulties in obtaining students visas (especially in scientific and technical fields), rising U.S. tuition costs, vigorous recruitment activities by other English-speaking nations, and perceptions abroad that it is more difficult for international students to come to the United States."

Increasing global competition for the best students has added to the drop in the numbers of international students. While these reasons may be the most significant deterrents for all international students, such observations do not adequately answer why the number of Arab students has been disproportionately reduced.

The numbers of visitors for business and pleasure has similarly decreased. Businessmen and tourists from the Gulf went from 84,778 in 2000 to 25,005 in 2004, a 70.5 percent decrease. The number of Egyptian visitors dropped 51.5 percent, from 48,904 in 2000 to 23,742 in 2004. The decrease in the number of both visitors and students from Morocco, Jordan, and Lebanon was also significant but lower than that of Egypt and the Gulf states. The causes for these declines have not been investigated although some researchers cite visa delays and fears of discrimination.

Security-Related Policy and Arab Americans

Another consequence of 9/11 has been the increased monitoring of Arab and Muslim Americans for security reasons. Although most FBI interviews of Arab and/or Muslim Americans have been conducted voluntarily, the increased attention has caused tension, nervousness, and concern to many individuals, as well as community leaders and organizations.

A two-year study conducted by the Vera Institute of Justice and funded by the National Institute of Justice, a research agency of the U.S. Department of Justice, confirmed that 9/11 had a substantial impact on Arab Americans and their perceptions of federal agencies, particularly the FBI. The report states, "Although community members also reported increases in hate victimization, they expressed greater concern about being victimized by federal policies and practices than by individual acts of harassment or violence."

A major issue of concern remains the 2001 Patriot Act and its provisions that allow increased surveillance without approved court orders. The number of people who have been charged or convicted for terrorism under the act is unclear. In June 2005, President Bush stated that over 400 charges were made as a result of terrorism investigations, but in almost all of these cases, the federal prosecutors chose to charge the plaintiffs with nonterror charges, such as immigration violations. Under the Patriot Act, anyone asked for information about an individual or group of people by the FBI has a gag order placed on them, regardless of whether the identity of the individual becomes public knowledge.

In December 2005, President Bush confirmed that he authorized warrantless searches in which the National Security Agency (NSA) monitored phone calls and emails from possibly thousands of citizens and others in the United States who contacted persons abroad.

Despite the former NSA director’s reassurances that the program was targeted and focused on persons associated with Al Qaeda, Arab Americans are concerned about the legality of warrantless searches, and the program has increased feelings of being targeted and put under surveillance due to their ethnic background and contact with friends and family in the Middle East. In 2006, several organizations filed lawsuits challenging the legality of warrantless domestic spying as well as the release of thousands of customer phone records by BellSouth, AT&T, and Verizon, citing violation of privacy.

In addition, in 2003, the Department of Homeland Security implemented the National Security Entry/Exit Registration System (NSEERS), which required males over the age of 16 from certain countries who had entered the United States since October 2002 to report to immigration offices to be photographed and fingerprinted on an annual basis.

Shortly after NSEERS was implemented, immigration authorities fingerprinted, photographed, and questioned 80,000 men. It is not known how many individuals were Arab, but 19 out of the 25 countries on the NSEERS list were Arabic-speaking. Although the main features of this program were suspended in December 2003, nationals of some countries — Iraq, Iran, Libya, Sudan, and Syria — are still bound by the NSEERS requirements.

As a result of NSEERS and other initiatives, the number of deportations from the Arab countries on the NSEERS list and an additional five predominantly Muslim countries also on the list increased 31.4 percent in the two-year period following 9/11. The percentile rise in deportation orders for nationals of other countries was 3.4 percent in comparison. Human rights, civil liberties, and Arab-American organizations believe these facts point to a trend of profiling and patterns of selective enforcement of immigration laws.

Together, these security and immigration measures have given the impression that the U.S. government believes Arabs and Muslims to be a suspicious and dangerous group to whom constitutional rights and liberties do not apply.

Looking Ahead

One of the long-term consequences of 9/11 was a questioning of identity and the outward expression of ethnicity and religion. In the last five years, many Arab Americans have asked themselves, How do I present myself when the mention of my ethnicity and/or religion is enough to make others uncomfortable?

While some have decided to hide their heritage or privilege another ethnic background — also the reaction of some German Americans after World War I and Japanese Americans after World War II — others have channeled this dilemma into artistic expression. As a result, Arab-American arts have blossomed. Fiction and poetry — particularly by Arab-American women — art exhibits, and comedy acts have found their way into the public domain, giving Arab Americans a more human face.

However, heightened security fears and recent terrorist attacks in Europe have kept the Arab American community under the microscope of the FBI and NSA. The perception of surveillance that dominates many local and national-level discussions between Arab Americans and these agencies is not likely to decrease unless pending lawsuits result in the courts finding the warrantless searches or the release of phone records to be unconstitutional and a violation of due process or privacy.

While the flow of immigrants has remained slow but steady, the number of students and visitors has slowed down substantially. Although these decreases are unlikely to isolate Arab Americans from their friends and family in the Middle East and North Africa, it may indicate a decrease in the interactions between people who are Arab and live in the Middle East and Americans who live in the United States. In the current political climate, it seems there is a growing need for cultural exchanges — yet the opportunities for those very cultural exchanges are declining.

Sources

Arab American Institute Foundation. "Arab American Demographics." Available online.

Brittingham, Angela and de la Cruz, G. Patricia. 2005. "We the People of Arab Ancestry in the United States." Census 2000 Special Reports #21. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington DC. Available online.

De la Cruz, G. Patricia and Angela Brittingham. 2003. "The Arab Population: 2000." Census 2000 Brief. U.S. Census Bureau. Available online.

Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics. "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2005" Table 3. Legal Permanent Resident flow by region and Country of Birth: Fiscal Years 1996 to 2005. Available online.

Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics. "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics" Table 23 in 2003 + 2004, Table 25 in 2002, Table 36 in 2001 + 2000. Nonimmigrants admitted by selected class of admission and region and country of citizenship.

Haddad, Yvonne. 1998. "The Dynamics of Islamic Identity in North America." In Muslims on the Americanization Path? Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 19-46.

Henderson, Nicole J., Christopher W. Ortiz, Naomi F. Sugie, and Joel Miller. 2006. "Law Enforcement and Arab American Community Relations After September 11, 2001: Engagement in a Time of Uncertainty." Vera Institute of Justice. Available online.

Institute of International Education. 2005. "U.S. Sees Slowing Decline in International Student Enrollment in 2004/05." Press release. November 14. Available online.

Jachimowicz, Maia. 2003. "Foreign Students and Exchange Visitors." Migration Information Source. September 1.

Reed, Cheryl L. 2005. "Government wages uphill battle in search for Arabic translators: Four years after 9/11 attacks, U.S. still short of qualified linguists." Chicago Sun-Times. December 18, p. A18.

Samhan, Helen Hatab. 1999. "Not Quite White: Race Classification and the Arab-American Experience" In Arabs in America: Building a New Future, edited by Michael W. Suleiman. Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press. Available online.

Suleiman, Michael. 1999. Arabs in America: Building a New Future. Edited by Michael W. Suleiman. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

U.S. Census Bureau, Foreign-born profiles by region and country of birth. Available online.