You are here

The World Is Witnessing a Rapid Proliferation of Border Walls

A construction crew works on a wall the U.S.-Mexico border. (Photo: Mani Albrecht/U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

In a matter of months in late 2021, Poland’s parliament approved the building of barbed-wire fencing along its border with Belarus, the governor of Texas inaugurated sections of 30-foot-tall steel-bollard barriers abutting Mexico financed by state and private funds, and Israel completed an underground “iron wall” equipped with sensors on the edge of its border with Gaza. Around the same time, Turkey reinforced its stone wall on the Iranian border, while Greece completed a 25-mile steel wall separating itself from Turkey and made plans to appeal to the European Union for support to add even more sections.

No continent has been spared from the reinforcement and fortification of borders, which has come to define the beginning of the 21st century. Seventy-four border walls exist across the globe, most erected over the last two decades; at least 15 others were in some stage of planning as of this writing. A large share of these walls, particularly the new ones, are designed to prevent illegal immigration, although they have not proven wholly effective in this regard. But walls can also mark the legacy of wartime defenses, aid the halting of smuggling, and seek to prevent terrorist attacks.

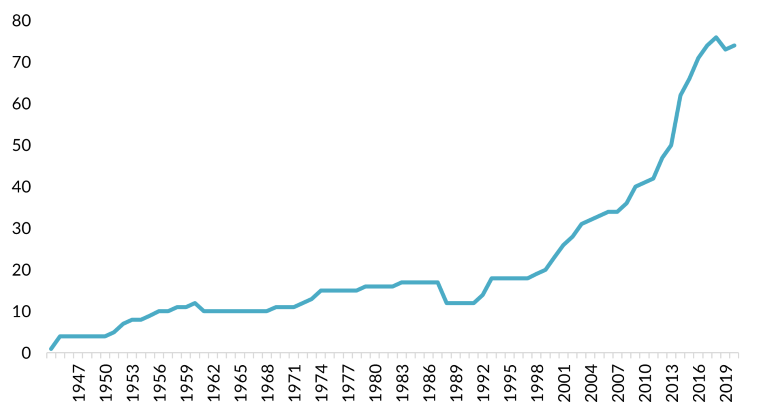

While the idea of barriers between countries is centuries old, the phenomenon has taken on a scale unprecedented in history. There were fewer than five border walls globally when World War II ended, and less than a dozen at the fall of the Berlin Wall and end of the Cold War, which seemed to mark the victory of democracy and foretell the obsolescence of borders in favor of an era of expanded capitalism and liberalism. Sometimes seen as mere lines between two sovereign states, sometimes not even clearly demarcated, borders were previously somewhat (albeit not always) more flexible and permeable than they are today. This was the case especially in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War.

Yet, the post-Cold War evolution towards a global village was a delusion that lasted only a decade. The reterritorialization of the world and its delineations made a comeback, and in the years since borders have become gradually more demarcated as well as harder, reinforced, more fortified, and better armored. They have morphed into symbols of states’ entrenchment behind ramparts designed to address asymmetric, unconventional, and global threats, including unwanted flows. Once supposedly antiquated, walls have become gradually normalized solutions to geopolitical tensions and remedies to the instability generated by an unbalanced international system. This article reviews the ancient and recent history of border walls to show the rapid increase in construction since the turn of the millennium.

Defining Border Walls

What is a border wall? The terminology is crucial since the same piece of physical infrastructure can take on many names. So much depends on who is speaking about it; the chosen label will vary from one context to another, including terms including “walls,” “fences,” “barriers,” and “fortifications,” and connote a range of ideas including security, separation, terror, or shame. The UN General Assembly, the International Court of Justice, and several researchers have chosen to use “wall” as an overarching term that takes into account all manner of border fortifications.

Therefore, it is worth considering the wall as an encompassing concept comprising three main aspects. First, it has a masonry foundation; whether it is made of a succession of cemented fenceposts, an assemblage of solid blocks of concrete, or extensive barbed-wire fencing, it is fixed and hence not mobile. Secondly, it delineates the border between regular points of entry. Finally, its functions are to assert a border or territorial claim or, alternately, to prevent the crossing of specific people and goods such as migrants or drugs.

The wall differs from the border itself in a few ways:

- It is unilateral, in that it is built by only one party (although both sides can build opposing walls), whereas the border line is, in principle, agreed upon by the neighboring states.

- It follows approximately the demarcation line while remaining within the sovereign territory of the constructing state.

- The wall only encompasses a marginal aspect of the border, reducing it to one of its most restrictive dimensions; where, by definition, a border is first and foremost an interface that connects two countries, a wall makes the juncture hard and sealed.

- Lastly, the concept of the wall includes an accompanying surveillance apparatus that may include sensors, border roads, lighting, cameras, checkpoints, or drones meant to enhance the wall’s impermeability.

Uses of Walls throughout History

For centuries, barriers have defined territorial boundaries of ancient states, cities, and districts. Among the oldest exemplars: the Germanic limes and other fortifications built by Romans, including the walls of Antonine, Hadrian, Aurelian, and the Theodosian triple wall, many of which were built more than two millennia ago. Older still were some of the walls in Mesopotamia: the first wall thought to have been built to demarcate a territorial border (rather than as a rampart around a city) is Sumerian King Shulgi of Ur’s 250-kilometer-long wall built around 2038 BCE between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers to prevent Amorite invasions. The Sasanian-era Great Wall of Gorgan (also known as the Red Snake defense system) was built between 420 CE and 530 CE in what is now northern Iran. The Danish Dannevirke was built across the neck of the Jutland peninsula around the 9th century. Sungbo’s Eredo and the Iya of Benin, in Nigeria, date to 800 to 1000. The Genkō Bōrui, erected seven centuries ago in Japan, was a 20-kilometer stone wall along Hakata Bay designed to halt invading Mongol forces. The 15th century Silesian Walls run through parts of what is now Poland. And the multiple walls of China, which were begun during the Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644), spanned several hundred years of construction.

There are still debates over the functions of these historical walls, whether they were strategic or demographic filters, meant to assert the grandeur of an empire or to ensure its defense. But what is clear is that the idea itself is an old one. During the 20th century, apart from the Iron Curtain, an array of defensive walls was constructed, including the Maginot Line, the Alpine Wall, and the Atlantic Wall ahead of or during World War II in Europe. There were also colonial walls, including the Morice Line in Algeria, occupation walls such as the Bar Lev Line along the Suez Canal, and delimitation walls such as the Green (Attila) Line in Cyprus.

The end of the Cold War and fall of the Berlin Wall appeared to sanction the end of a world articulated around borders and state territories. Indeed, the accelerating pace of globalization (understood here as the intensification and densification of global flows, whether people, goods, or capital) in the following decade fueled a narrative that rapidly pointed towards a world without borders or sovereignty. Perhaps no case was more illustrative of this trend that the European Union, and particularly the Schengen area, where international movement became increasingly seamless. In this perspective, mobility of money, goods, and eventually individuals became core to the global system. Walls, which were archetypes of immobility and fixity, seemed to belong to a bygone era.

However, walls did not disappear completely from the geopolitical scene. And since the turn of the 21st century and the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, borders have returned to play a central role in international relations and domestic politics. Borders have become thicker, sometimes stretching well above and beyond the border, as exemplified by Washington’s resurrection of a policy dating from a 1953 regulation that allows U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to operate, with extraordinary powers, within 100 miles of any land or sea border, which encompasses a zone in which approximately two-thirds of the U.S. population lives. Borders have also become more complex, expanding inside as well as outside of the national territory they demarcate. Indeed, border controls can be performed well beyond the demarcation line, as in the case of authorities’ preclearance policies to carry out immigration controls from travelers’ points of departure, and by private actors such as airlines and security contractors. However, what truly differentiates this era from previous times is that there have never been more physical walls at the border than recent years.

Figure 1. Number of Border Walls Globally, 1945-2022

Source: Update by Élisabeth Vallet of statistics included in Élisabeth Vallet, ed., Borders, Fences and Walls: State of Insecurity? (Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2014).

Border Walls Today

At a global level, the number of border fortifications has multiplied. There were only a dozen border walls at the end of the Cold War, but the number has since more than sextupled. The fortification of borders has accelerated throughout every corner of the world, to the rhythm of events and crises both national and international, under the cover of imminent dangers both real and supposed that have provided authorities with justification and legitimacy for constructing costly infrastructure.

The COVID-19 pandemic has confirmed this trend. The speed with which borders were closed on multiple occasions amid the outbreak goes hand in hand with the notion that a border can be hermetically sealed, which is central to the concept of a border wall. In a few cases over the past two years, the pandemic has even been the primary justification for erecting new fences. This was the case for China in its Yunnan Province along Myanmar’s Shan State, and by South Africa at the Beitbridge border post with Zimbabwe on the Limpopo River. Government reflexes to seal off their countries and point to outsiders as bearers of contagion are in line with history. The 18th century construction of a “plague wall” in southern France illustrates both the durability of this idea centuries later as well as the vacuity of this infrastructure, since that episode failed to slow the epidemic.

Costs of Border Walls

Border walls are expensive. In 2008, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) evaluated the cost of building barriers along the U.S.-Mexico border at $1 million to $4.5 million per mile, taking into account everything from expropriation of private property to construction. Recently, this cost has reached $21 million per mile in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley, or even up to $46 million per mile according to Biden administration figures. In Israel, the initial estimate of $1 million per mile has risen to up to $5 million per mile in some cases. Meanwhile, the European Union contributed 250 million euros to the construction of barbed-wire fences around the Spanish enclave city of Ceuta, after financing 75 percent of the first barrier built between 1995 and 2000. And in 2022, Lithuania and Poland are expected to spend 172 million euros and 353 million euros respectively fortifying their border with Belarus.

Maintenance costs are also high. In 2011, CBP estimated the cost to maintain the U.S.-Mexico barrier at $6.5 billion over 20 years. For one year alone, the Department of Homeland Security evaluated maintenance costs at $274 million in fiscal year (FY) 2017. Similarly, Israel spent an estimated $260 million on repairing its West Bank fence each year as of 2014.

How Border Walls Are Used

During and shortly after World War II, walls often reflected the conversion of a conflict’s front line into a de facto border, freezing a zone of tension in a fortified and artificial peace. Walls such as those separating the two Koreas, between India and Pakistan, or in Cyprus correspond to that category. They were rather prevalent in the last century and still account for 21 percent of contemporary walls, according to the author's calculations.

Since the beginning of the millennium, things have changed. Most of the walls standing today are aimed at filtering, slowing down, and prohibiting selected individuals and goods from outside. Twenty-four percent are primarily designed to prevent smuggling and 32 percent are mostly intended to halt unwanted immigration, among them flows at the U.S.-Mexican border, between India and Bangladesh, and around Hungary. The remainder (23 percent) are directed at preventing terrorism and are typified by those in Israel, Saudi Arabia, and in Central Asia’s Ferghana Valley where Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan meet. In this sense, walls evolve alongside global trends; anchored to globalized borders that embrace instruments such as preclearance, they are one way for states to combat what they perceive to be the downsides of globalization such as mass migration, illicit trafficking, and the erosion of state sovereignty.

Figure 2. Governments’ Primary Motivations for Constructing Border Walls

Source: Update by Élisabeth Vallet of statistics included in Élisabeth Vallet, ed., Borders, Fences and Walls: State of Insecurity?

Walls’ intended purposes may evolve, wherein lies the challenge of decoding states’ official discourses. Officials’ motivations can fluctuate over time and for a single wall, invoking at one moment concerns about terrorism and the next economic threats from migration.

Evolution of Walls in a Globalized Age

As state sovereignty is challenged by globalization, leaders have turned to walls as a method of controlling global flows. States have been losing control of both financial flows and their supply chains while wealth inequalities have increased, particularly since the 2008 financial crisis. In this environment of a poorly regulated and unevenly shared globalization, walls offer a tangible artifact that political figures can brandish at the edge of their state's territory to show a semblance of control. The claim by Donald Trump shortly after assuming the U.S. presidency in 2017 that “a nation without borders is not a nation” is therefore no coincidence. For a national audience who may feel that the true powerbrokers are outside the government’s reach, the wall restores meaning in a global world.

This reality was accelerated by the 9/11 attacks, which shook the United States and subsequently the rest of the world, then by the repercussions of the Arab Spring which reverberated across the European Union. In a context where potential threats came from abroad, partly because borders had not filtered out nefarious actors, border security quickly emerged as a solution. As the international system became unstable and mutual trust and cooperation gradually eroded, walls gradually became a symbol of fixity and stability. Then, as the instability of the international system spread across continents and political regimes, construction of walls thus became an almost standardized, normalized, “off-the-shelf” response by leaders of all types.

Building a wall appeals now to both authoritarian and democratic regimes. Research shows that three categories of factors can influence the fortification of a border: the nature of the balance of power between bordering states and particularly the existence of a certain asymmetry, the behavior of neighbors, and events of international significance such as terrorist attacks or large-scale population movements. This was the case in response to regional security dilemmas such as the recent one in which Belarus instigated the movement of asylum seekers and other migrants across its territory to reach the borders of Poland and Lithuania, an act described by some as using migration as a weapon against the European Union. Walls have been the response, also, to violent non-state actors such as those operating along Turkey’s Syrian border. European leaders have wielded barriers as a tool to mitigate weaknesses of migration policies following the crisis of 2015 and 2016 in the European Union’s south and east. Hence, issues that were once peripheral, localized, and belonged to the remit of border police are now matters of national security that justify border militarization.

Do Border Walls Work?

There is no denying that walls have become commonplace. What is perhaps most notable is that they have been erected in areas that previously had opposed them, as in Europe (where the Berlin Wall had become a symbol of oppression), and promoted by countries that had traditionally championed free trade as the foundation of prosperity and global stability, such as the United States. While president, Trump argued on Twitter in January 2019 that the fact that so many walls were being built around the world proved they were effective:

There are now 77 major or significant Walls built around the world, with 45 countries planning or building Walls. Over 800 miles of Walls have been built in Europe since only 2015. They have all been recognized as close to 100% successful. Stop the Crime at our Southern Border!

Trump’s assertion leads to a circular justification: the “Build the Wall” slogan swept tautologically throughout the world, giving grounds in return for more construction, and hence more legitimacy.

Yet the claim that walls have been nearly universally “successful” could not be further from the truth. Research from around the world indicates that both the direct and indirect costs of building border walls exceed the benefits. Tunnels, drones, ladders, ramps, document forgery, and corruption—the strategies for circumventing the walls end up multiplying. Walls do not achieve the objectives for which they are said to be erected; they have limited effects in stemming insurgencies and do not block unwanted flows, but rather lead to a re-routing of migrants to other paths. As migrants take other routes, circumventing the obstacles and therefore becoming more difficult to monitor, they rely more on smugglers and as a result pay greater costs. This is a process that many studies have shown, for instance along the U.S.-Mexico border and between Israel and the West Bank. As border enforcement increases, so do smugglers’ profits and the presence of organized crime.

While walls make the border area more rigid by transforming the periphery from a slightly permeable membrane into a stiff barrier that can only stretch to a breaking point, they also tend to isolate. Their erection inside the constructing state’s territory and along the border line allows for the creation of enclaves where, for instance, populations are trapped between the wall and the border, or trapped outside their farmlands. This has been the case for some people in Bangladesh, Texas, and the West Bank. Walls also have a significant impact on the local environment and ecosystems. Some residents of Poland, for instance, fear the impact of the planned border fence with Belarus, which will cut across the ancient Białowieża Forest, a UNESCO World Heritage site, while precious water in Arizona's Quitobaquito Springs have been depleted during wall construction.

Moreover, border barriers disconnect previously interdependent economies, leading to the erosion of border communities' social fabric. As additional controls or detours dramatically increase border crossing times, they impact the fluidity of legal exchanges, frequently leading to the decline of local economies and the fostering of a black market. By disrupting regular movement, walls alter the cooperation and negotiation of people and organizations that exist across the borders, hampering communities’ capacity to mitigate local and national crisis.

Globally, the new age of border walls reflects the dysfunctions of globalization. New fortifications are responses to countries’ real or imagined external threats often tailored to domestic audiences, in a more globalized but less stable world. In the absence of effective multilateral responses to many shared challenges, including the often-intractable ones related to the spontaneous movement of irregular migrants and would-be asylum seekers, leaders have turned to walls to seal themselves off. In doing so, the wall hides the other side of the border, both physically and virtually. This bolsters the rigidification of the border.

Walls end up producing more instability without solving the problems they were intended to address. They do not allow for a lasting halt to the flows of people and goods they are supposed to stop. Instead, border walls get circumvented and breached. Yet each time they are, is, to their supporters, a demonstration of their necessity.

In a way, border walls’ inability to completely halt irregular movement is key to their political longevity. They constitute a territorialized remedy to challenges that do not originate at the border where they are erected, but far outside of the national territory and sometimes the other side of the globe, where foreign policy might be a more effective tool. It could be they are simply not designed for that purpose in the first place, and are merely symbolic. It is precisely this symbolic weight that could guarantee not only their perennial nature but also their multiplication in years to come.

Sources

Agier, Michel. 2016. Borderlands: Towards an Anthropology of the Cosmopolitan Condition. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Carter, David B. and Paul Poast. 2020. Barriers to Trade: How Border Walls Affect Trade Relations. International Organization 74 (1): 165-85.

Chappell, Bill, Tamara Keith, and Merrit Kennedy. 2017. 'A Nation without Borders Is Not a Nation': Trump Moves Forward with U.S.-Mexico Wall. National Public Radio, January 25, 2017. Available online.

Gemantsky Anna, Guy Grossman, and Austin L. Wright. 2019. Border Walls and Smuggling Spillovers. Quarterly Journal of Political Science 14 (3): 329-47. Available online.

Flores, Esteban. 2017. Walls of Separation: An Analysis of Three ‘Successful’ Border Walls. Harvard International Law Review 38 (3): 10-12.

Jones, Reece. 2012. Border Walls: Security and the War on Terror in the United States, India, and Israel. London: Zed Books.

---. 2016. Borders and Walls: Do Barriers Deter Unauthorized Migration? Migration Information Source, October 5, 2016. Available online.

Karasz, Palko. 2019. Fact Check: Trump’s Tweet on Border Walls in Europe. The New York Times, January 17, 2019. Available online.

Klibanoff, Eleanor and Uriel J. García. 2021. Gov. Greg Abbott Inaugurates First Stretch of State-Funded Border Barrier in Starr County. Texas Tribune, December 18, 2021. Available online.

Massey, Douglas S., Jorge Durand, and Karen A. Pren. 2015. Border Enforcement and Return Migration by Documented and Undocumented Mexicans. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (7): 1015-40. Available online.

Miller, Todd. 2019. Empire of Borders: The Expansion of the U.S. Border Around the World. London: Verso.

Minca, Claudio and Alexandra Rijke. 2017. Walls! Walls! Walls! Society and Space, April 18, 2017. Available online.

Nowak, Katarzyna, Bogdan Jaroszewicz, and Michał Żmihorski. 2021. Poland’s Border Wall Will Cut Europe's Oldest Forest in Half. The Conversation, December 15, 2021. Available online.

Nuñez-Nieto, Blas and Michael John Garcia. 2007. Border Security: The San Diego Fence. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Rubio Salas, Rodolfo. 2011. Cambios en el Patrón Migratorio y Vulnerabilidades de los Migrantes Indocumentados Mexicanos con Destino y Desde Estados Unidos. Madrid: Fundación Ciudadanía y Valores.

Ruiz Benedicto, Ainhoa, Mark Akkerman, and Pere Brunet. 2020. A Walled World Towards a Global Apartheid. Barcelona: Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau, Transnational Institute, the Palestinian Grassroots Anti-Apartheid Wall Campaign, and Stop Wapenhandel. Available online.

Saddiki, Said. 2017. World of Walls: The Structure, Roles and Effectiveness of Separation Barriers. Cambridge, UK: OpenBook Publishers. Available online.

Vallet, Élisabeth. 2020. State of Border Walls in a Globalized World. In Borders and Border Walls: In-Security, Symbolism, Vulnerabilities, eds. Andréanne Bissonnette and Élisabeth Vallet. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Vallet, Élisabeth and Charles-Philippe David. 2014. Walls of Money: Securitization of Border Discourse and Militarization of Markets. In Borders, Fences and Walls: State of Insecurity? ed. Élisabeth Vallet. Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing.