You are here

Revolution and Political Transition in Tunisia: A Migration Game Changer?

Tunisia has seen skyrocketing unemployment, particularly among university-educated youth, spurring contemporary emigrant waves and contributing to discontent leading to the 2011 revolution. (Photo: Amine Ghrabi)

With more than 1.2 million Tunisians living abroad in 2012 out of a total population of 11 million, Tunisia is, and has long been, a prime emigration country in the Mediterranean region. Dating to the country’s independence in 1956, Tunisian emigration has been heavily dominated by labor migration to Western Europe, especially to the former colonial power, France. From the mid-1970s onwards, Libya emerged as a destination for migrant workers, while family migration became the main entry pathway to traditional European destinations.

In the 1980s, Italy became increasingly attractive for low-skilled Tunisian workers due to its geographical proximity and the absence of immigration restrictions. After Europe restricted its visa regime and strengthened border controls in the early 1990s, permanent settlement, irregular entry, and overstaying became structural features of Tunisian emigration. More recently, soaring unemployment among tertiary-educated youth has triggered new flows of student and high-skilled emigration, especially to Germany and North America.

Both under Habib Bourguiba, Tunisian president between 1956 and 1987, and his successor Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who ruled from 1987 until his ouster in 2011, Tunisia’s emigration policy was characterized by two principles: encouraging workers to emigrate and monitoring Tunisians living abroad. Only since the turn of the 21st century have Tunisian policymakers addressed immigration from sub-Saharan Africa, partly due to Tunisia’s role as both a destination and transit country for migrants en route to the European Union (EU).

The emphasis of EU policymaking on irregular migration across the Mediterranean over the past two decades has turned Tunisia into a significant player in the Euro-African migration system. Tunisia’s 2011 revolution, which sparked the Arab Spring, has accelerated the design and implementation of new migration and asylum laws amid significant flows from Libya and to Europe.

This country profile explores migration trends in Tunisia from the period of colonial settlement to the aftermath of the Arab Spring, including the diversification of emigrant destinations and growing inflows of African migrants, as well as government diaspora engagement policies and migration cooperation with European countries. With Tunisian democracy in its early stages and continuing violence and instability next door in Libya, the future of Tunisia’s migration flows and policy approaches remain uncertain.

Linking Migration and the Revolution

Despite Tunisia’s image as an economically prosperous, secular, and progressive country—notably regarding women’s rights—many Tunisians faced daily struggles over the past decade. Structurally high unemployment and lack of prospects particularly affected university graduates and workers in economically neglected interior regions. At the same time, the spread of social media made it possible to bypass state censorship and publicly expose the politically repressive and economically corrupt regime of President Ben Ali, exacerbating societal discontent.

Despite a harsh crackdown and arrests, mass protests following the self-immolation of street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi on December 17, 2010 in Sidi Bouzid, a small town in the center of the country, launched the revolution that culminated in the toppling of President Ben Ali on January 14, 2011, after 23 years in power.

From the outset, revolution and migration were intrinsically linked. The economic crisis in Europe, resulting in lower tourism and declining exports, as well as the tightening of immigration and border controls, reduced both job prospects at home and migration opportunities for Tunisians. This reinforced the discontent of the country’s educated youth. At the same time, the underlying causes of the revolution—rising unemployment, spreading poverty, and political repression—fueled Tunisians’ emigration aspirations.

The immediate effect of the revolution on migration was three-fold: First, the security void led to the effective absence of Tunisian border controls in early 2011. This resulted in a temporary hike in irregular emigration to Europe and propelled trans-Mediterranean migration to the top of the European political agenda.

Second, several hundred thousand people crossed the border from Libya into Tunisia in early 2011 following the overthrow of the Ghaddafi regime. For Tunisia, which had not experienced high immigration since colonial times, this prompted immediate practical challenges of accommodation, health care, and food provision, and required the interim government to elaborate new migration and asylum laws after many years of inactivity in this policy field.

Finally, the democratization process and unprecedented increase in civil liberties after 2011 triggered significant civil-society activism. Thousands of new nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) were established in Tunisia to advocate for more dignity, freedom, and human rights—including the rights of migrants at home and abroad. This led to increased involvement of Tunisian emigrants in domestic politics and monitoring of Tunisian policymaking processes by civil society.

|

Figure 1. Map of Tunisia

|

|

Source: Central Intelligence Agency, “The World Factbook: Tunisia,” updated May 13, 2015, www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ts.html. |

Colonial Settlement

Emigration from Tunisia gained importance only in the second half of the 20th century. Immigration, however, was a key feature of colonial Tunisia. Historically, Italians were the largest migrant community in Tunisia due to Italy’s geopolitical interests and proximity. Around 80,000 Italians lived in Tunisia at the end of the 19th century, many working in small handicraft businesses, fishing, or farming.

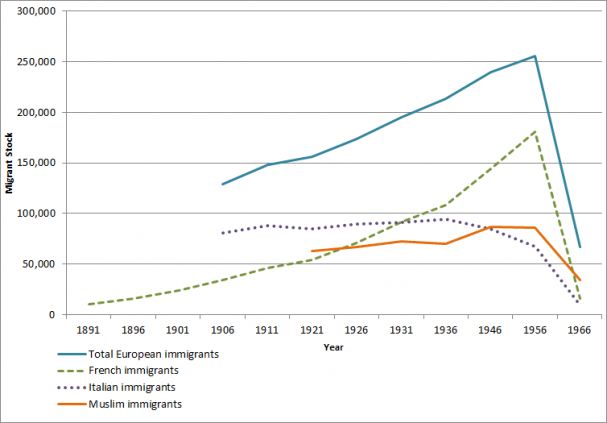

After France colonized Tunisia in 1881, authorities encouraged the arrival of French settlers to work either in the public sector (administration, schools) or as farmers. France promoted the cultivation of Tunisian land in order to substantiate French sovereignty. Not until the 1930s, however, did the French outnumber Italians in Tunisia. By the end of World War II, nearly 350,000 foreigners were living in Tunisia—six times the current foreign-born population—mostly from France, Italy, Libya, and Algeria (see Figure 2).

Within ten years of independence from France in 1956, 70 percent of the foreign population had left Tunisia. European departures were triggered by the brief skirmish between French and Tunisian military forces around the Bizerte military base in July 1961, as well as the nationalization of foreign-owned agricultural land in May 1964. Many Libyans left after significant oil resources were discovered in Libya in the late 1950s. And while the 1954-62 Algerian war of independence led approximately 200,000 Algerian refugees to cross into Tunisia, 85 percent quickly returned following Algerian independence in 1962.

|

Figure 2. Evolution of Migrants Living in Tunisia, 1891-1966

|

|

Source: Mahmoud Seklani, La population de la Tunisie (Paris: Comité International de Coordination des Recherches Nationales de Démographie [CICRED], 1974). |

The Recruitment Era

Unlike in Morocco and Algeria, colonial settlement was not mirrored by Tunisian emigration; significant outflows only took off after independence. Tunisian cooperation in labor recruitment with a number of Western European states played an important role in shaping post-independence migration flows, although spontaneous emigration occurred as well. In the 1960s, the Tunisian government signed bilateral labor agreements, first with France (1963), then Germany (1965), Belgium (1969), and the Netherlands (1971).

In 1967, the Tunisian government created the Emigration Direction Office under the Ministry of Social Affairs to organize departures to Europe. The 1972-75 development plan set an annual target of 60,000 emigrants to relieve the labor market and boost the economy through remittances. To increase the number of job placements, Tunisia sent civil servants abroad to sign contracts with European employers for Tunisian workers.

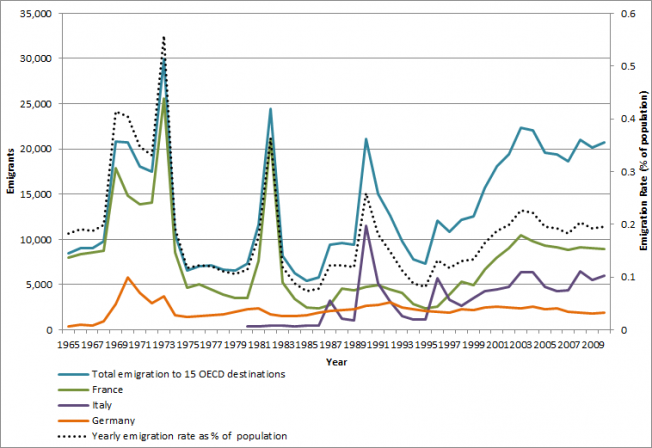

Emigration to Europe accelerated in this period, fueled by economic growth in the receiving countries, and unemployment in Tunisia (see Figure 3). Although the target was never met, an estimated 25,000 Tunisians emigrated annually to Europe, mainly France and to a lesser extent Germany, in the peak years 1969-73. Tunisian migrants mainly worked in construction, industry, and agriculture, performing both low-skilled and specialized jobs. With active recruitment and professional training by the Emigration Direction Office, by the early 1970s, the skill level of Tunisians in France overtook that of Moroccan and Portuguese migrants.

Emigration drastically dropped when European countries halted recruitment in 1973-74 in the aftermath of the oil crisis. In the long run, however, European policies to reduce the number of low-skilled labor migrants were ineffective due to three factors. First, labor market demand in Europe and high unemployment in Tunisia continued to provide migration incentives. Second, Tunisians increasingly used family and student migration channels in reaction to waning legal opportunities to migrate as workers, and overstaying visas became a common phenomenon. Finally, many Tunisians abandoned their previous circular or seasonal migration movements and settled permanently in Europe due to the gradual tightening of European immigration policies.

|

Figure 3. Evolution of Annual Tunisian Emigration to Main Western Destinations, 1965-2010

|

|

Notes: Emigration flows to the following 15 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries are included: Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Israel, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. Only bilateral corridors with an annual average of more than 500 migrants are displayed separately. There is no consistent flow data available for Tunisian migration to Libya. Source: International Migration Institute, University of Oxford, DEMIG C2C database (2014 version), www.migrationdeterminants.eu. |

Diversification of Emigration

From the mid-1970s, labor migration partly shifted to neighboring Libya, where economic growth created employment opportunities. There is evidence that Tunisian migration to Libya even overtook migration to France in the second half of the 1970s, according to geographer Allan Findlay. Diplomatic relations between Tunisia and Libya were, however, tense, and Libya effectively used migration as a political weapon. Despite recruiting thousands of Tunisians yearly based on a 1971 agreement between the two countries, Libya on several occasions carried out mass expulsions of Tunisian workers following diplomatic incidents. Bilateral relations improved in 1987, and in 1988 free mobility was introduced between the two countries.

In the 1980s, Italy emerged as a new European destination for Tunisians, a position it still holds. Due to geographic proximity and the absence of Italian entry rules for foreign workers then, it was relatively easy for Tunisians to travel to Italy and work in the formal and informal labor markets, especially in agriculture. Given that Tunisians did not need a visa to enter Italy until September 1990, circular migration dominated. Typically, migrants went to Italy for several months to earn money, then traveled home to live with their families for the rest of the year.

In addition to the diversification towards Libya and Italy, the composition of Tunisian emigration progressively changed. After Western European states restricted entry requirements for low-skilled workers in 1973-74, circular migration was replaced by the increasingly permanent settlement of Tunisian migrants in France and other European destinations. Simultaneously, legislation in European states enshrined migrants’ right to family reunification. This provided new migration opportunities, and family reunification rapidly became the primary legal pathway for Tunisians to enter Europe.

With European countries further increasing immigration controls in the early 1990s—in particular after the introduction of French and Italian visa requirements for Tunisians in 1986 and 1990, respectively—many migrants resorted to irregular entry and overstaying. Although the scale of irregular migration is difficult to estimate, the peaks in Figure 3 attest the importance of this phenomenon: The 1981 peak corresponds to a regularization in France that granted legal status to 22,000 Tunisians (more than any other nationality). Italian amnesties in 1986, 1990, and 1995 also granted legal status to several thousand Tunisians.

Emigration Policies: An Economic and Political Safety Valve

Since independence, Tunisia’s emigration policy has been two-fold: Workers were encouraged to emigrate to stimulate the economy through remittances and relieve domestic unemployment. Meanwhile, the government closely monitored migrants, both to secure close ties with the diaspora and to dissipate political engagement and criticism of the regime from abroad.

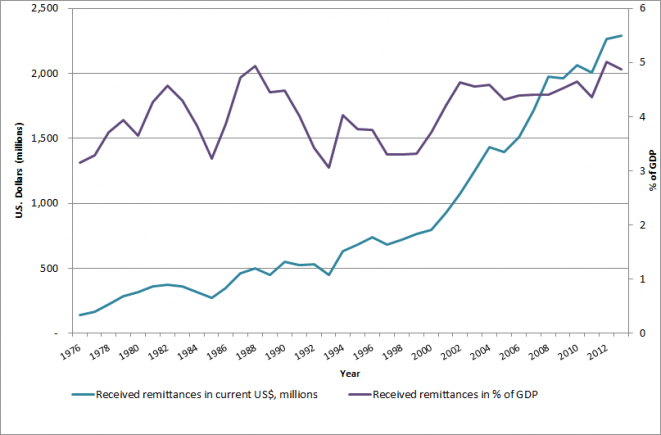

Remittances have played a significant role in Tunisia’s economy over the past five decades, accounting for at least 4 percent of annual gross domestic product (GDP) (see Figure 4). In order to attract further investments, Tunisia in the mid-1980s relaxed currency exchange controls and allowed expatriates to open bank accounts in convertible Tunisian dinars.

In June 1988, the Office for Tunisians Abroad (OTE) was created, placing Tunisia among the early adopters of diaspora engagement policies. The OTE has progressively expanded its activities to court Tunisian emigrants, providing legal and logistical assistance to citizens and relatives abroad, cultural programs to sustain and deepen the attachment with Tunisia, information and facilitation for saving and investing in Tunisia, and support for reintegration after return. In the same spirit, Tunisia launched a national television program targeting communities abroad, financed Arabic language classes for second-generation migrants, organized special events to familiarize Tunisian emigrant businessmen with the country’s investment opportunities, and, in August 1995, created an annual national day for Tunisians residing abroad.

|

Figure 4. Annual Officially Recorded Remittances to Tunisia, 1976-2013

|

|

Source: Source: World Bank, “World Development Indicators,” accessed January 24, 2015, http://databank.worldbank.org/data/views/variableSelection/selectvariables.aspx?source=world-development-indicators#. |

While encouraging emigration, the Tunisian state also sought to control its citizens abroad, particularly to prevent involvement in labor unions or political activities. From the 1970s onwards, Tunisia—following the Algerian and Moroccan approaches—created amicales (friendship societies) in France and other Western European countries, whose leaders were members of Tunisia’s ruling party and in charge of surveying emigrant communities.

When Ben Ali came to power in 1987, one of his first decisions was to grant the right to vote to Tunisian emigrants. Although motivated by the need to gain political support, Ben Ali’s decision was nevertheless welcomed by emigrant communities as a sign of political opening. But the liberalization was short-lived: after the 1989 presidential elections and in the wake of growing Islamist movements in neighboring Algeria, Ben Ali reverted to authoritarianism. This was visible in the regime’s treatment of emigrants—the role of the amicales in suppressing political opposition in France was reinforced and the government arbitrarily denied the renewal or delivery of passports to some members of the opposition.

Tunisia’s Emigrant Population Today

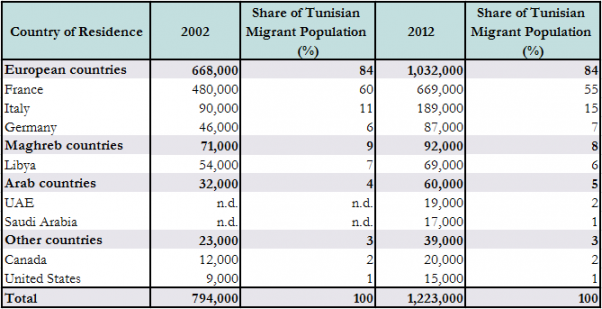

In 2012, the Tunisian Ministry of Foreign Affairs recorded 1,223,000 Tunisians living abroad—more than 11 percent of the country’s total population, up from 8 percent (794,000) of the population in 2002. And while the majority of Tunisian emigrants still reside in France (55 percent), Italy has clearly cemented its role as the second most important destination (15 percent), while Germany has also consolidated its attractiveness (7 percent).

|

Table 1. Geographic Distribution of Tunisian Emigrants, 2002 and 2012

|

|

Note: These numbers are taken from registration at Tunisian consulates and include second- and third-generation migrants who have taken on the nationality of the country of residence. Figures reported by destination countries are thus often much lower. Sources: Office des Tunisiens à l’Etranger (OTE)/Direction de l’Information et des Relations Publiques (DIRP), Répartition de la Communauté tunisienne à l’étranger 2012 (Tunis: OTE/DIRP, accessed January 15, 2015), www.ote.nat.tn/fileadmin/user_upload/doc/Repartition_de_la_communaute_tunisienne_a_l_etranger__2012.pdf; Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, CARIM database, “Demographic and Economic Module – Tunisia,” accessed January 15, 2015, www.carim.org/index.php?callContent=59&callTable=1803. |

Until the 1990s, Tunisian emigrants were mostly low- or semi-skilled workers or family members. Today, high unemployment among university graduates (see Figure 5) and the expansion of migration opportunities for high-skilled workers in Europe and North America have led increasing numbers of university-educated Tunisians to emigrate. Student migration has also risen, as next to France (25,000 students in 2008), Germany (6,000) and North America (4,500) have become prime education destinations in recent years. This trend might have been further fueled by the 2008 global economic crisis and increasing youth unemployment and frustration.

|

Figure 5. Tunisian Unemployment Rate in Percentage of Active Population, 2004-14

|

|

Sources: Institut National de la Statistique (INS), “Enquête Nationale sur la Population et l'Emploi, Tableau 8 et 10” (Tunis: INS, accessed January 22, 2015), www.ins.nat.tn; Azzam Mahjoub, Labor Markets Performance and Migration Flows in Tunisia: National Background Paper (Florence: European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, 2009), www.carim.org/public/workarea/home/Website%20information/Literature/Labour%20Market%20and%20Migration/2lmmfinal3tunisia.pdf. |

Emerging Regional Immigration

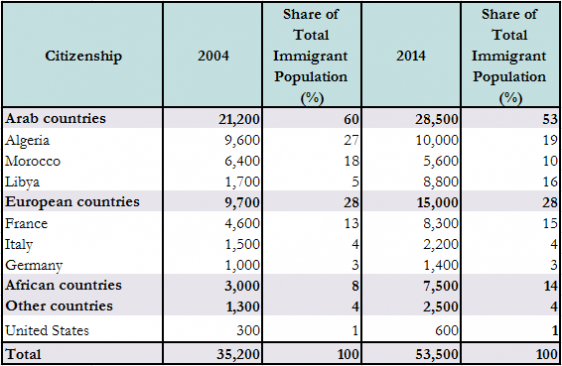

Since the departure of colonial settlers after independence, immigration to Tunisia has remained low. Just 53,500 foreigners (0.5 percent of the population) were registered in Tunisia according to the 2014 census, the majority from the Maghreb (53 percent) and Europe (28 percent), especially France (see Table 2). Most immigrants are high school or university graduates, reflected in the fact that two-thirds work in high-skilled jobs.

Compared to 2004, the number of Libyans and other African nationals has increased, partly as a result of political and economic instability in the wider region. Like Morocco, Tunisia has become increasingly popular among sub-Saharan African students with about 2,500 enrolled in Tunisia’s higher education system. Additionally, the relocation of the African Development Bank from Côte d’Ivoire to Tunisia in 2003 has attracted growing numbers of highly skilled African migrants to Tunis.

|

Table 2. Number of Immigrants Living in Tunisia, by Country of Citizenship, 2004 and 2014

|

|

Source: Institut National de la Statistique (INS), Recensement général de la Population et l’Habitat 2014 (Tunis: INS, 2015, accessed April 27, 2015), http://rgph2014.ins.tn/sites/default/files/rgph-chiffres-v3.pdf. |

Despite the overall low number of foreigners and dominance of Maghrebi and European immigrants, public discourse since 2000 has focused on irregular migrants from sub-Saharan Africa. Indeed, Tunisia has become a destination and transit country for migrants fleeing political persecution and economic crises on their way to Europe—although to a lesser extent than Libya or Morocco. Estimations of the number of irregular migrants in Tunisia are highly unreliable, but even generous estimates rarely exceed 10,000. Another indicator is the number of irregular migrants intercepted at the border; over the 2012-14 period, Tunisian authorities arrested around 5,000 foreigners attempting to leave Tunisia irregularly.

As Tunisia does not require travel visas for many sub-Saharan countries including Guinea, Mali, Niger, and Senegal, entry through land and air borders is easy and their stay legal for the first three months. Most of these migrants spend some time in Tunisia working in tourism or agriculture in preparation for their journey to Italy—either through Sicily or Lampedusa. However, sub-Saharan migrants regularly face police controls on the street and risk being sent to temporary reception centers and returned to their country of origin if found without legal status.

Policymaking, Readmission, and Regional Diplomacy

Before the 2011 revolution, Tunisia’s legal framework on immigration was based on two laws enacted in 1968 and 1975 that regulated the entry and stay of foreigners and dealt with passports and travel documents for Tunisians. Similar to other North African countries, Tunisia has ratified the 1951 Geneva Convention and its 1967 Protocol, but not yet established a national refugee protection system. However, Tunisia has not ratified the 1990 International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families.

Immigration enforcement emerged on Tunisia’s political agenda only at the turn of this century, partly in reaction to European calls to prevent irregular migration. On February 3, 2004, Tunisia introduced Law 2004-6 tackling smuggling and irregular migration. Migrants’ rights organizations criticized the law for heavily sanctioning anyone who facilitates, even involuntarily, a person’s irregular entry or exit. Though aimed at human smugglers, the sanctions can be applied de facto to anyone failing to report contact with irregular migrants, including family members, lawyers, or doctors. The 2004 migration law not only served Ben Ali’s government in responding to European expectations and thus consolidating the international legitimacy of his regime, but was also a tool and pretext for the authoritarian state apparatus to increase surveillance of Tunisian society, according to scholar Jean-Pierre Cassarino.

Law 2004-6 was the first national immigration legislation enacted by Tunisia in decades. Previously, migration control was primarily dealt with through bilateral agreements. Typically, negotiations revolved around Tunisia requesting eased entry rules for its nationals and European countries calling for more effective readmission procedures of irregular migrants. For instance, in 1998, Italy and Tunisia signed a readmission agreement and in return, Italy allocated an annual quota of 3,000 work permits for Tunisians.

However, these agreements were generally poorly implemented. Tunisian authorities only repatriated 25 percent of irregular migrants for which Italy had requested travel documents. And while the Italian quota for Tunisian workers was met in 2000 and 2001, the number dropped to an annual average of 700 in the 2002-08 period, possibly in retaliation for Tunisia’s noncompliance.

France also has struggled in carrying out readmissions of irregular Tunisian migrants. In 2008, both countries signed an agreement of concerted migration management and solidarity development, aimed at granting facilitated access to the French labor market for 9,000 highly qualified Tunisian workers yearly, in return for stronger control of irregular migration and intensified cooperation on readmission. Again, Tunisian authorities delivered only 25 percent of travel documents requested by France in 2009, and in retaliation, only 3,000 Tunisians benefitted from the facilitated work permit procedure in 2010 and 2011.

Political Transition: A Challenge and Window of Opportunity

The Tunisian revolution ended the repressive and corrupt rule of President Ben Ali in January 2011. Subsequently, Tunisia’s first free elections were held in October 2011, bringing the moderate, Islamist Ennahda Party into power. Following the adoption of a new constitution in January 2014, parliamentary and presidential elections were held in October and November, respectively, with the secularist Nidaa Tounes Party winning a plurality. Beji Caid Essebsi was elected president, replacing 2011-14 interim President Moncef Marzouki.

As mentioned above, the revolution led to an immediate surge in irregular emigration. In early 2011, Italian authorities recorded the arrival of 43,000 people at its sea borders, including 28,000 Tunisians, compared to an annual average of 19,000 people (including 1,700 Tunisians) over the 2000-10 period. Soaring unemployment rates, favorable weather conditions for sea crossings, and a security void leading to the effective absence of Tunisian border controls likely prompted the sudden increase. The fact that irregular entries into Spain and Malta decreased over the same period also suggests that irregular migrants from the region adapted their routes, abandoning other crossing points—such as from Libya into Italy or Morocco into Spain—to take advantage of the poorly controlled Tunisia-Italy route.

The temporary hike in irregular migration, in combination with the revolution and emergence of new actors on Tunisia’s political scene, was seen in Europe as a potential challenge to established migration cooperation. Would the new government break with the past migration management framework or would democratization allow a further deepening of political cooperation?

In February 2011, the EU border control agency, Frontex, started Joint Operation Hermes to support Italy in addressing growing crossings from Tunisia and Libya. Bilaterally, Italy quickly deployed diplomatic efforts to reduce migration from Tunisia. On April 4, 2011, then Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi visited the head of the Tunisian interim government; the following day, the two countries signed an agreement on cooperation against irregular migration.

Since the temporary hike in 2011, irregular migration from Tunisia has decreased, according to Frontex apprehension data. In 2012, 2,200 Tunisian irregular migrants were intercepted at European sea borders; the number dropped to less than 1,000 in 2013 and 2014. This is partly due to the restoration of border controls by Tunisian authorities and increased EU financial and technical support, but also to Libya’s increased role as a departure point for irregular migration. Meanwhile, more than 15,000 Tunisians were forcibly returned from Europe between 2011 and 2013.

In March 2014, Tunisia and the European Union signed a Mobility Partnership as a negotiation framework for future cooperation on readmission, border controls, and visa facilitation. So far, no concrete policies have emerged. Although Tunisia’s new government seems willing to continue its long-standing cooperation with the European Union, the new domestic political context might impact the way in which this cooperation manifests. Today, while cooperation with the European Union is still economically vital, it is no longer critical for the government’s political survival and legitimation. Instead, the growing activism of Tunisia’s civil society increases the government’s democratic accountability for its policy decisions, particularly when infringing on the rights of Tunisian migrants abroad or immigrants on Tunisian soil.

Immigration from Libya and the Asylum Question

Within less than a year of the revolution, more than 345,000 migrants entered Tunisian territory fleeing the civil war in Libya, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Of this count, nearly 137,000 were returning Tunisians, while the remainder were foreign nationals, mostly Egyptians, Bangladeshis, Sudanese, and Chadians. Other estimates range as high as half a million people crossing the Libyan-Tunisian border in 2011.

The sudden presence of foreign nationals and refugees challenged Tunisia’s governmental and societal approaches to immigration. Emergency measures were taken by Tunisian authorities, including the opening of the Choucha refugee camp in February 2011—which received up to 18,000 people a day at the peak of the crisis—and the signing of a cooperation agreement with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in July 2011. Tunisia’s humanitarian organizations also mobilized their resources to support incoming migrants. Expansive media coverage of this welcoming attitude contributed to creating a sense of national unity coherent with the overall enthusiasm following the toppling of the old regime.

By the time UNHCR closed the Choucha camp in 2013, most residents had returned to their countries of origin, more than 3,000 refugees had been resettled, and 4,000 people were granted refugee status in Tunisia via UNHCR. However, several hundred were left without a Tunisian residence permit. To redress their legal situation, and that of future immigrants and refugees, the new Tunisian government launched its first national strategy on migration in August 2013. This included the elaboration of a legislative framework on immigration, asylum, and human trafficking. Tunisia’s new constitution, ratified in 2014, enshrined additional protections for migrants, such as laws regulating detention and the right to political asylum. Together with UNHCR, Tunisian authorities are also developing a national refugee determination system, with implementation expected in 2015.

Migration from Libya to Tunisia continues as Libya’s political and economic instability, civil war, and growing Islamist threat have prompted thousands of Libyans and foreigners to leave. In contrast to the welcoming attitude in 2011, the government now emphasises Tunisia’s role as a transit country: foreigners arriving from Libya are only allowed to enter if they can prove their immediate exit. In response, Egypt, for instance, has implemented a repatriation program for its citizens fleeing from Libya to Tunisia. IOM has also started a voluntary return program for African migrants in Tunisia, and between 2012 and 2014 more than 600 migrants, mostly from Nigeria, Gambia, and Côte d’Ivoire, were repatriated. Libyan citizens are still granted the right to stay in Tunisia under the condition that they not engage in political activity that could jeopardize relations between the two countries.

The Empowerment of Tunisian Civil Society at Home and Abroad

Next to changing migration patterns, the role of Tunisia’s civil society has evolved, both within the country and among the diaspora. Under Ben Ali, civil society associations were closely monitored by the state, and migration was considered a particularly sensitive topic kept in the hands of the Ministry of Interior, the Office for Tunisians Abroad (OTE), and the amicales. Civil-society activism on migration before the revolution was thus limited. The radical increase in civil liberties after the revolution, as well as the sudden presence of significant numbers of immigrants in Tunisia, prompted increased advocacy by Tunisian actors on migrants’ rights.

On the one hand, Tunisian associations in Europe such as the Democratic Association of Tunisians of France (ADTF) and the Union of Tunisian Migrant Workers (UTIT) began operating in Tunisia, linking the call for more migrants’ rights in Europe to requests for better treatment of migrants in Tunisia. On the other hand, associations such as the Centre of Tunis for Migration and Asylum (CeTuMa) and the Association of Families Victims of Irregular Migration (AFVIC) were created in Tunisia, providing support for refugees and the families of irregular migrants who had died crossing the border. These new NGOs challenge Tunisia’s security-driven cooperation with the European Union and advocate a human-rights-based immigration policy.

Changes were also visible in the new government’s approaches to Tunisian emigrants. Most importantly, Tunisians abroad were given a say in domestic politics when Order 1088 of August 3, 2011 attributed them 18 parliamentary seats (out of 217) ahead of the October elections. This decision was welcomed by Tunisian emigrants and nearly 40 percent of those eligible abroad cast votes, compared to a 60 percent voter turnout in Tunisia. Other political moves by the transition government included the creation of a Secretary of State for Tunisian Expatriates (SEMTE) in October 2011, a High Council for Tunisians Abroad, an Agency for Migration and Development, and a National Migration Observatory. In its 2013 national strategy on migration, Tunisia aimed to increase remittances to 10 percent of GDP by 2020 (currently 4 percent) and to attract 4,000 highly qualified returnees.

Looking Ahead

Tunisian migration dynamics have clearly evolved over the past decades, and the observed changes have been both a trigger for and an outcome of the 2011 political transition. The new domestic and regional context alters the socio-political framework in which migration policy is formed. Faced with new forms of migration, the Tunisian government is developing new policies for both incoming migrants and refugees and the Tunisian diaspora. Under Ben Ali, migration policy was primarily seen as a tool to consolidate the international credibility of his authoritarian regime and to mobilize migrants as an economic safety valve. Today, the democratically elected government must take into account domestic calls for more dignity, human rights, and freedom in their migration policies to assure political legitimacy and social stability.

Yet, other factors, such as regional security, economic development, and tourism, will feed into the future of Tunisian migration. If Tunisia continues struggling to restructure the labor market and to attract economic investments, high unemployment is likely to persist and fuel dissatisfaction. At the same time, Islamist groups at the borders with Algeria and Libya might challenge the democratization process and could compel politicians to favor security over liberties. In this context, Tunisian emigration will likely continue at a high level, driven by political discontent and economic precariousness.

If, however, Tunisia continues its path towards stability, democracy, and economic growth, then youth unemployment is likely to decrease. In the long term, Tunisia’s labor market might even create an increasing demand for immigrant labor. Finally, the inclusion of Tunisia’s active civil society in the elaboration of a new legal framework on migration could lead to a more human-rights-based approach to migrants in Tunisia and abroad and serve as a role model for other countries in the Mediterranean region, both in Africa and across the sea in Europe.

Acknowledgments

The research underlying this article is part of the International Migration Institute's DEMIG project (www.migrationdeterminants.eu) and has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) / ERC Grant Agreement 240940. The author thanks Hein de Haas for his comments on earlier drafts, as well as Simona Vezzoli and María Villares-Varela for their central role in collecting the DEMIG C2C migration database.

Sources

Bel Hadj Zekri, Abderazak. 2008. La dimension politique de la migration irrégulière en Tunisie. CARIM Analytic and Synthetic Note 2008/53. Florence: European University Institute (EUI), Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS). Available Online.

---. 2011. La gestion concertée de l'émigration entre la Tunisie et l'Union Européenne: Limites des expériences en cours. CARIM Analytic and Synthetic Note 2011/49. Florence: EUI, RSCAS. Available Online.

Ben Achour, Souhayma and Monia Ben Jemia. 2011. Révolution tunisienne et migration clandestine vers Europe: Réactions européennes et tunisiennes. CARIM Analytic and Synthetic Note 2011/65. Florence: EUI, RSCAS. Available Online.

Boubakri, Hassan. 2013. Migrations internationales et révolution en Tunisie. Migration Policy Centre Research Report 2013/01. Florence: EUI, RSCAS. Available Online.

Boubakri, Hassen and Sylvie Mazzella. 2005. La Tunisie entre transit et immigration: Politiques migratoires et conditions d’accueil des migrants africains à Tunis. Autrepart 4 (36): 149-65.

Brand, Laurie A. 2002. States and Their Expatriates: Explaining the Development of Tunisian and Moroccan Emigration-Related Institutions. Working Paper 52, University of California, San Diego. Available Online.

---. 2010. Authoritarian States and Voting From Abroad: North African Experiences. Comparative Politics 43 (1): 81-99.

---. 2013. Arab Uprisings and the Changing Frontiers of Transnational Citizenship: Voting from Abroad in Political Transitions. Political Geography 41: 54-63.

Cassarino, Jean-Pierre. 2000. Tunisian New Entrepreneurs and Their Past Experiences of Migration in Europe: Resource Mobilization, Networks, and Hidden Disaffection. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

---. 2012. Hiérarchie de priorités et système de réadmission dans les relations bilatérales de la Tunisie avec les États membres de l’Union européenne. Maghreb et Sciences Sociales: 239–55.

---. 2014. Channelled Policy Transfers: EU-Tunisia Interactions on Migration Matters. European Journal of Migration and Law 16: 97-123.

Central Intelligence Agency. 2015. The World Factbook: Tunisia. Updated May 13, 2015. Available Online.

Chandoul, Mustapha and Hassan Boubakri. 1991. Migrations clandestines et contrebande à la frontière tuniso-libyenne. Revue européenne des migrations internationales 7 (2): 155-62.

Consortium for Applied Research on International Migration (CARIM) database. N.d. Demographic and Economic Module - Tunisia. Florence: EUI, RSCAS. Available Online.

de Haas, Hein and Nando Sigona. 2012. Migration and Revolution. Forced Migration Review 39: 4-5. Available Online.

El-Khawas, Mohamed A. 2012. Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution: Causes and Impact. Mediterranean Quarterly 23 (4): 1-23.

European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union (FRONTEX). 2014. Annual Risk Analysis 2014. Available Online.

European External Action Service (EEAS). 2013. Relations Tunisie-Union Européenne: Un partenariat privilégie. Plan d’action 2013-2017. Brussels-Tunis: EEAS. Available Online.

European Commission. 2011. A Partnership for Democracy and Shared Prosperity with the Southern Mediterranean. COM(2011)200 final, March 8, 2011. Brussels: European Commission. Available Online.

---. 2014. Déclaration conjointe pour le Partenariat de Mobilité entre la Tunisie, l'Union Européenne et ses Etats membres participants. Brussels: European Commission, DG Home Affairs. Available Online.

Fargues, Philippe and Christine Fandrich. 2012. Migration after the Arab Spring. Migration Policy Centre Research Report 2012/09. Florence: EUI, RSCAS. Available Online.

Findlay, Allan M. 1980. Patterns and Processes of Tunisian Migration. Unpublished PhD thesis, Department of Geography, University of Durham.

Forum Tunisien Pour Les Droits Economiques et Sociaux (FTDES). 2013. Les Tunisiens disparus en mer en 2012. Tunis: FTDES.

Global Detention Project. 2014. Tunisia Detention Profile July 2014. Available Online.

Hibou, Beatrice. 1999. Tunisie: le coût d’un ‘miracle’. Critique Internationale: 48–56.

International Migration Institute (IMI). N.d. DEMIG C2C database (2014 version). University of Oxford: IMI. Available Online.

---. N.d. DEMIG POLICY database (2014 version). University of Oxford: IMI. Available Online.

---. N.d. DEMIG VISA database (2014 version). University of Oxford: IMI. Available Online.

Institut National de la Statistique (INS). 2015. Recensement général de la Population et l’Habitat 2014. Tunis: INS. Available Online.

---. N.d. Enquête Nationale sur la Population et l'Emploi. Tunis: INS. Available Online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2014. Tunisia - IOM Migrants Statistical Overview: Assisted Voluntary Return, Reintegration and Resettlement. Available Online.

Mahjoub, Azzam. 2009. Labor Markets Performance and Migration Flows in Tunisia: National Background Paper. Florence: EUI, RSCAS. Available Online.

Migration Policy Centre (MPC). 2013. Tunisia Migration Profile. Florence: EUI, RSCAS. Available Online.

Mzali, Hassen. 1997. Marché du travail, migrations internes et internationales en Tunisie. Revue Région et Développement 6: 151-83.

Natter, Katharina. 2014. Fifty Years of Maghreb Emigration: How States Shaped Algerian, Moroccan and Tunisian Emigration. IMI Working Paper 95, International Migration Institute, University of Oxford. Available Online.

Office des Tunisiens à l’Etranger (OTE)/Direction de l’Information et des Relations Publiques (DIRP). N.d. Répartition de la Communauté tunisienne à l’étranger 2012. Tunis: OTE/DIRP. Available Online.

Radio France Internationale (RFI). 2014. Frontière tuniso-libyenne: Tunis hausse le ton à l'égard des étrangers. August 3, 2014. Available Online.

Seklani, Mahmoud. 1974. La population de la Tunisie. Paris: Comité International de Coordination des Recherches Nationales de Démographie (CICRED).

Simon, Gildas. 1973. L'émigration tunisienne en 1972. Méditerranée 15 (4): 95-109.

State Secretariat for Migrations and Tunisians Abroad (SEMTE). 2013. Stratégie nationale de migration. Tunis: Ministry of Social Affairs, SEMTE.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2013. UNHCR Closes Camp in South Tunisia, Moves Services to Urban Areas. News release, July 2, 2013. Available Online.

World Bank. N.d. World Development Indicators. Washington DC: World Bank. Available Online.