You are here

The Multicultural Dilemma: Amid Rising Diversity and Unsettled Equity Issues, New Zealand Seeks to Address Its Past and Present

A wall of flowers pays tribute to victims of the Christchurch attacks. (Photo: Luis Alejandro Apiolaza)

The devastating reality of extremist racism hit New Zealand on March 15, 2019 when a gunman shot and killed 51 unarmed Muslims during worship at a mosque in Christchurch. Amid the grief and shock that followed, the response of New Zealanders—across ethnic, racial, and religious backgrounds—caught the world’s attention. From the image of Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern in a headscarf comforting a Muslim woman, to news stories of thousands from all walks of life attending mosque services or standing in protective solidarity in a line behind Muslims as they kneeled in prayer in public, there was an unprecedented outpouring of unity and support for the affected community. “They Are Us” became the defining catchphrase following the attacks, setting the stage for a national resolve around diversity and inclusion.

Box 1. Bicultural and Multicultural New Zealand?

In New Zealand, biculturalism—accorded by the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi signed in 1840—refers to the coexistence of two distinct cultures: Māori (indigenous) and non-Māori in partnership. Since the 1970s, the government of New Zealand has attempted to articulate and institutionalize a more bicultural society by emphasizing Māori language and culture, and addressing issues of equality, historical marginalization, and land ownership. Many, however, critique biculturalism for not going far enough to advance Māori culture and consider it to be superficial.

In recent years, others have pushed for a multicultural New Zealand that recognizes that the country is home to many peoples and cultures. Bicultural advocates have expressed concern that a multicultural focus diminishes state-recognized rights for Māori, while others argue that multiculturalism is important for New Zealand’s future.

However, the road from resolve to inclusion is far from straightforward. New Zealand’s multiculturalist approach, derived from its unique political and economic history, has delivered some successes but has also left uneven social cohesion. The question that deserves attention is whether the strategies of the past can be tenable for the future, especially with regards to migration and integration policy.

This article will explore key issues in New Zealand’s diversity policymaking to outline the opportunities for—and challenges to—fostering multiculturalism, drawing on a range of official documentary and research evidence including the author’s work in this area. The article situates multiculturalism against the backdrop of biculturalism and the historical obligations of the British Crown to the country’s indigenous Māori people under Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi; henceforth, Te Tiriti). It then discusses the influence of neoliberalism on migration policies that, especially in the last decade, stratified the population, impacting prospects of inclusion among migrant and ethnic communities. Finally, the article reflects on the future of New Zealand as a multicultural society.

Box 2. Definitions

The term “migrant” has a different connotation in New Zealand as compared with North America or Europe, and there is more considerable overlap with the term “ethnic” than is the case elsewhere. The term “ethnic” is reserved for arrivals who are not of Pākehā (European), Māori, or Pacific origin, and is widely used to refer to peoples from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, for example. Most, but not all, ethnic people are migrants, many having moved to New Zealand in the last 30 years.

Terms such as “new settler” and “recent migrant” are used to distinguish between those who have arrived within two to five years and those who have been here longer, who legally transition into “permanent residents” or citizens. Until recently, there was a relative ease in transitioning from recent migrant to permanent resident and citizen, further closing the gap between migrants and ethnic people.

Further, New Zealand, which experienced significant emigration until 2012, counts returning nationals in its international migration arrival statistics.

New Zealand’s Migration History

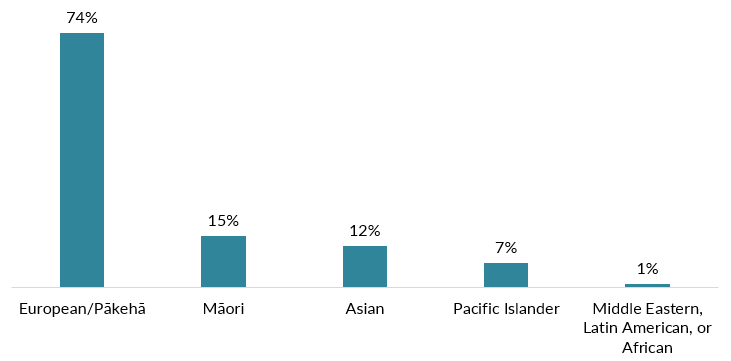

New Zealand’s population of just under 5 million people is made up of five major groups: Pākehā (European); indigenous Māori; Asian; Pacific Islander; and Middle Eastern, Latin American, or African (see Figure 1). The group with the largest population increase is Asian; between 2006 and 2013, the estimated growth rate for the Asian-origin population was 33 percent—while proportions of European-origin New Zealanders are in decline. There has also been a rise in Māori and Pacific populations, both youthful ones with nearly half under the age of 20. The Asian-origin population is prevalent in New Zealand’s largest city, Auckland, where those born in countries such as China, India, Philippines, Sri Lanka, and South Korea make up around one-quarter of the city’s residents, up from 5 percent in 1991. With at least 200 different ethnicities, nationalities, and religious and language diversities, Auckland is now considered a “superdiverse” city.

Figure 1. New Zealand Population by Major Ethnic-Origin Group, 2013

Notes: The totals add up to more than 100 percent because respondents could report belonging to more than one ethnic group. While a census was conducted in 2018, findings have yet to be released at this writing, making the 2013 one the most recent.

Source: Statistics New Zealand, “Major Ethnic Groups in New Zealand,” updated January 28, 2015, available online.

The history of migration to New Zealand and subsequent settlement can be traced back nearly 800 years. Beginning around 1300, Māori voyagers arrived in waka (canoes) from Hawaiki, the traditional Māori place of origin believed to be in East Polynesia, although their journey likely originated in Asia. They resettled in pockets across the breadth of the place they called Aotearoa (“the land of the long white cloud”). Over time, the land was divided by tribal boundaries. Currently, there are more than 100 recognized iwi (tribes) in New Zealand.

In the 18th century, Europeans arrived as settlers, traders, missionaries, explorers, and military personnel, bringing discord. Efforts to maintain peace among newcomer and Māori populations culminated in the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840. Considered New Zealand’s founding document, Te Tiriti established the relationship between the British Crown and Māori. It is also a contested document: written separately in both English and Māori, interpretations of the entitlements and rights it accords are disputed. Despite the intentions of its signers, Te Tiriti did not bring harmony, and instead the decades following its signing marked a period of demographic, social, and political devastation for Māori. Wars and disease from waves of European migration reduced their numbers drastically: in 1840, 98 percent of the population was Māori; by 1901, they comprised only 5.6 percent. Throughout much of the 20th century, as Māori experienced abject deprivation of lands, livelihood, culture, and language, New Zealand transformed into a settler colony of the British Empire.

The next major demographic transition followed changes to the Immigration Act of 1987. Until then, aside from British and Irish migrants, there were very small pockets of people coming from other countries and regions: Chinese prospectors arrived in the late 1800s in search of gold; Dutch and Indians came as farm laborers; Dalmatians and Croatians received Crown land for settlement; and Pacific Islanders arrived from Samoa, Tonga, Cook Islands, and Fiji. Amendments to the Immigration Act replaced race-based quotas, which favored migrants from the “mother country,” with a points-system aimed at attracting skilled labor to meet occupational shortages, in health care, agriculture, and other sectors. By the mid-1990s, migration from Britain and Ireland declined substantially as immigration from Northeast, South, and Southeast Asia rose substantially. By the turn of the 21st century, people from Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East were migrating to New Zealand as well, even as the country was also experiencing out-migration.

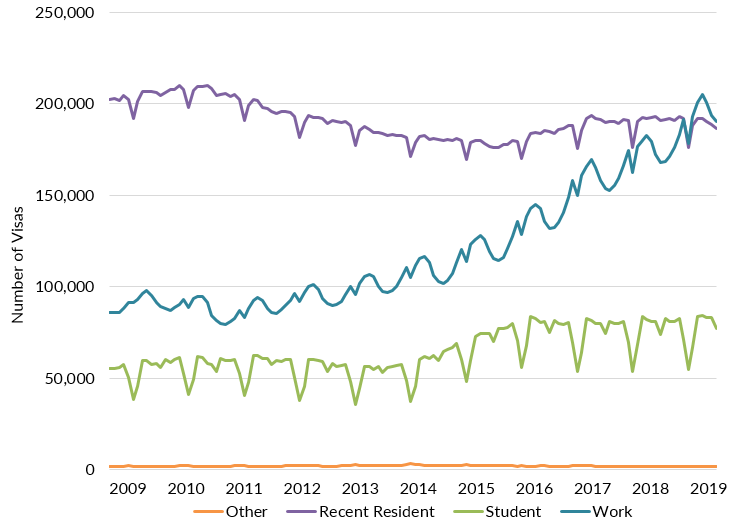

In the years following the immigration overhaul (often called a “period of optimism”), successive governments applied strictly regulated criteria to attract highly qualified professionals or businesspeople and others as long-term migrants to become permanent residents and, in due course, citizens. This goal remained until around 2010 when further changes to immigration policy shifted the focus away from permanency and settlement to a suite of temporary and short-term conditions to reside and work in the country.

Figure 2. Migrant Population by Visa Type, 2009-19

Note: Recent resident refers to residents who emigrated from New Zealand, but later returned.

Source: Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment, “Population by Visa Type,” Migration Data Explorer, accessed August 6, 2019, available online.

Discrimination and Diversity

Racial and ethnic diversity, for much of New Zealand’s history, was unequivocally met with antagonism. Māori, as noted, were subject to systemic marginalization from all spheres of society and with significant intergenerational impacts. Activism from young, urban-based Māori, rural leadership, and anti-racist Pākehā gathered force in the 1960s and 1970s, resulting in a renaissance of indigenous language and culture, and later, a political commitment to biculturalism. The Waitangi Tribunal was established in 1975 to settle historical claims of breach of the Te Tiriti by the Crown. Aside from the claims of individual iwi in relation to land and water resources, the tribunal has also reported on discrimination experienced by Māori in areas such as health and the criminal justice system.

Historically, other non-European ethnic groups were also subject to discrimination. In 1886, a poll tax was imposed on every Chinese person who entered New Zealand along with a limit on the number of Chinese who could enter the country, calculated in relation to tonnage of cargo on arriving ships carrying the passengers. An official apology was issued to New Zealand’s Chinese community in 2002. In the mid-1970s, Pacific Islanders were specifically targeted for deportation in the Dawn Raids on the grounds of overstaying visas. The representation of Asian migrants of the 1990s as the “yellow peril” in media and political rhetoric, and the demonization of Muslims in the aftermath of 9/11 are part of an ignominious racist history of the nation. There were also rising reports of the social dislocation of qualified foreign-born professionals, such as doctors, for whom migration resulted either unemployment or working in occupations far below their qualification, such as taxi driving.

Formal efforts at instituting multiculturalism were at best patchy until the turn of the 21st century when the Labour government led by Prime Minister Helen Clark made cultural diversity a key policy goal. Declaring that New Zealand would be enriched by its various cultures, a range of official initiatives were instituted. Among them, the high-profile Settlement Strategy delivered interpreter services, English-language classes, and other types of support for new migrants navigating the country’s employment, housing, education, and health systems. A stand-alone Office of Ethnic Affairs (later Communities) was established, the Race Relations Commission strengthened, and specialized policy units within ministries were set up to assist migrants and refugees. Community-based organizations and activities proliferated during this time to preserve diverse groups’ languages, cultures, and arts. Festivals and religious days from diverse cultures were celebrated across the country, including in Parliament. Ethnic-language media (television, radio, and newspapers) were also established. Industry also lauded superdiversity as giving New Zealand a business advantage. Perhaps, for these reasons, in 2015, New Zealand received the Global Creativity award from the Martin Prosperity Institute for being the most racially and ethnically tolerant country.

The accommodation of, and the freedom to practice, diverse languages, cultures, and religions is the foundational premise of New Zealand’s multiculturalism. These rights are further protected under the Human Rights Bill, which prohibits discrimination on grounds including race and ethnicity. Alongside, as citizens—and uniquely in New Zealand, even as permanent residents—ethnic minorities can participate in civil and political life, including voting and membership in political parties. Further, successive governments have engaged ethnic communities in grassroots consultations and forums, expanding spaces for political participation. Special protections are accorded to marginalized groups within ethnocultural communities, such as women; in recent years, Parliament passed special legislation against practices such as forced and underage marriages and female genital mutilation, and funded specialist services to combat and respond to domestic violence.

Evaluating Multiculturalism and Its Impacts on Migration

In the span of a decade, these initiatives have achieved significant progress. Despite this, there is substantive critique about New Zealand’s tryst with multiculturalism. Some scholars consider it a relatively integrated multiculturalism. A closer look, however, reveals that multiculturalism and migration in New Zealand have always been tied to—or, more precisely, sold on—the grounds of the economic benefits the country can garner. For example, political rhetoric around diversity has been encapsulated in phrases such as “diversity with growth,” or as “global talent management.”

The relationship between the economic and the cultural is tenuous and wavers, often at the behest of the party in government. Migration has been a pivotal focus of New Zealand’s main political parties (Labour and National), and over the last 30 years both have fine-tuned immigration policy to reflect their ideological predilections around national interests and economic priorities.

Between 2008-17, the conservative Fifth National Government accentuated an ideology of “neoliberal” diversity. Aimed at stimulating growth in the economy, the party enacted changes to migration policy that reflected economic differentiation among migrants. Instead of the long-standing focus on skilled and permanent long-term migrants and diverse pathways for entry, short-term migration was emphasized, a trend that continues even in the present government. Government substantially increased the number of temporary work visas for occupations such as nursing, dairy farming, care professions, and for seasonal horticultural work. In addition, visas for international students also grew, in part incentivized by new regulations that gave students conditional approval to remain and seek work once their studies were completed.

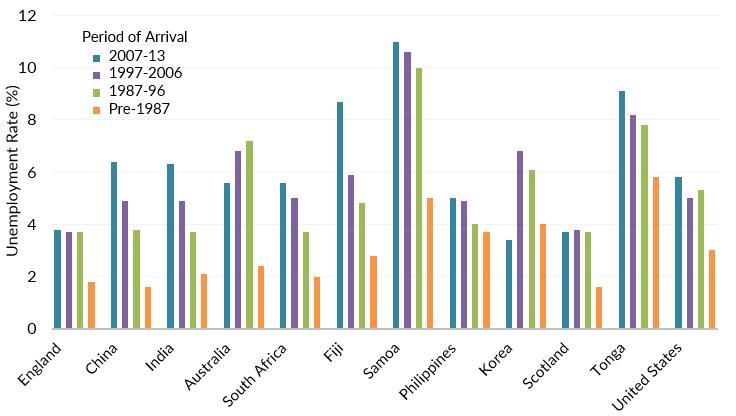

Many of those on temporary and conditional visas found themselves in low-paying and, often, exploitative work. Meanwhile, migrants in an investor category—those who could invest substantially in the country—were fast-tracked to residency. Overall, this differentiation resulted in a tiered system of migration; not only did it stratify migrants by class and income but at the lower income end it fostered a “subclass” of denizens in precarious economic, political, and legal circumstances. Recent research has found that this period of migration exacerbated inequality and deprivation among adult and adolescent migrants (see Figure 3). The widening income inequality has implications for a unified perspective of inclusion.

Figure 3. Migrant Unemployment Rates According to Period of Arrival

Source: Wardlow Friesen, “Quantifying and Qualifying Inequality Among Migrants,” in In the Intersections of Inequality, Migration and Diversification: The Politics of Mobility in Aotearoa/New Zealand, eds. Rachel Simon-Kumar, Francis Collins, and Wardlow Friesen (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

The Bicultural-Multicultural Dilemma

Akin to the tension between the economic and the cultural, New Zealand’s multiculturalism is also further defined by its commitments to biculturalism and Te Tiriti, which seeks redress for Māori; indeed, given the continued impact of historical injustices on ongoing inequities experienced by Māori, this is a fundamental obligation of the state. The express interest of Te Tiriti is to create a bicultural society, one in which Māori are not subject to the British Crown but rather are partners who have the right to self-determination.

Biculturalism, however, creates lack of clarity around multiculturalism. Multiculturalism assumes that Māori are just another minority group, a view that is strongly rejected across the spectrum. Instead, one view is to fold multiculturalism into biculturalism. From this perspective, Te Tiriti is conceptualized as a relationship between three entities: The Crown, Māori (who are tangata whenua: people of the land) and Pākehā (tangata tiriti: people of the Treaty). Although initially intended to establish relationships with the British, currently all other ethnic and migrant groups classify as tangata tiriti. This categorization within the Treaty relationship is entirely appropriate; in doing so, however, it groups “colonizer” and “colonized” populations together (for example, Indians and African nationalities are tangata tiriti along with Europeans), masking the marginalization of ethno-culturally diverse populations, and of the wider structures of racism and disadvantage that affect them as well.

In everyday translation, multiculturalism therefore bypasses issues of political rights for ethnic and migrant populations, specifically as a marginalized group. In many institutional spaces, biculturalism is framed as an equity issue, and multiculturalism as a diversity issue: the former requiring political restitution and the latter sociocultural accommodation. Formulas have been advanced to negotiate a common ground—frameworks such as “treaty-based multiculturalism” or “bicultural multiculturalism” among them—that demarcate the distinct political spaces for Māori and new migrants. These measures notwithstanding, the bicultural-multicultural dilemma is still unresolved. As generations of culturally diverse ethnic populations born in New Zealand grow in number, questions of political identity, rights, and entitlements will continue to surface.

Multiculturalism has also a long way to go in terms of representation. Even as Asian-origin residents make up nearly 12 percent of the population, corresponding representation in spaces of public and political decision-making are lacking. Although there are ethnic politicians in the major parties, their roles are aimed chiefly to cater to specialized constituencies, not the mainstream. Ethnic politicians, particularly women, who do not subscribe to this norm are subject to vitriolic attacks. A brief attempt to set up an Ethnic People’s Party in 2016 was quashed strongly on grounds that it signaled race-based politics.

In addition, there is also growing criticism that public declarations of inclusion by politicians are often not reflected within the halls of government. In a searing commentary following the Christchurch attacks, Muslim advocates charged that despite attending meetings with government officials over a period of years, their repeated appeals to address the growing threat of white nationalist groups was treated with indifference. Government officials have since acknowledged that the official focus has been on monitoring Islamic terrorism, not the dangers posed by white supremacists.

Against these layers of structural marginalization, it is not surprising that belonging and identity continue to be points of contention. One incisive analysis, for instance, demonstrated that newspapers tended to represent ethnic minorities as “New Zealand passport holders” rather than New Zealanders or New Zealand citizens. In stark contrast, a legitimate New Zealand identity for ethnic people is one that reifies difference. The author’s previous research highlighted that political identity for ethnic minorities meant a continual exercise of their difference, whether it was displaying their cultural variety, advocating for their needs or deficiencies within their communities, volunteering or participating in official events for ethnic people; there was an unwritten expectation that ethnic citizenship entails representing or acting on behalf of “their communities.”

Prospects and Promises

On balance, New Zealand’s diversity policies are an admixture of progress and predicaments as the terms of multiculturalism are shaped by historical, economic, and cultural imperatives. The strength of multiculturalism, as applied in New Zealand, is its recognition of difference, and this is an area where notable progress has been made. However, in a time of rising diversity, this recognition has not translated into broader political capital for ethnic minority populations. Multiculturalism is also strained between the instrumentalization of migration as an end to an economic goal, and a vision of a fair, equitable, and diverse society as its own ideal. In New Zealand’s recent history, political prioritization weighed in favor of the former. Diversity for its own sake, as a public good, and as a vision for a future society remains to be articulated.

Deep-seated racism as a barrier to social cohesion is currently at the center of discussions on multiculturalism and inclusion. While this is a critical focus, the turn cannot ignore the wider swath of structural anomalies that equally deserve attention.

So—where to from here?

The Labour coalition elected in 2017 brought with it fresh promise of renewed action on inclusiveness. If anything, the events of Christchurch only accentuate this urgency, precipitating a fundamental reassessment of inclusion in contemporary multi-ethnic New Zealand. If the responses post-Christchurch are an indication, a shift in the everyday encounters among diverse peoples is underway and one can hope for a greater willingness to participate in an honest dialogue about identity and belonging for all New Zealanders, regardless of their differences. Because it is not enough to acknowledge that “they are us;” it is equally important to ask who “we” are.

Sources

Auckland Council. 2014. Auckland Profile–Initial Results from the 2013 Census. Available online.

---. N.d. Auckland Plan 2050. Accessed July 8, 2019. Available online.

Bedford, Richard and Robert Didham. 2018. Immigration: An Election Issue That Has Yet to Be Addressed? Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online 13 (2):177-94.

Collins, Francis, Rachel Simon-Kumar, and Wardlow Friesen. 2019. Introduction: The Intersections of Inequality, Migration, and Diversification. In Intersections of Inequality, Migration and Diversification: The Politics of Mobility in Aotearoa/New Zealand, eds. Francis Collins, Rachel Simon-Kumar, and Wardlow Friesen. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Florida, Richard, Charlotta Mellander, and Karen King. 2015. The Global Creativity Index 2015. Toronto: University of Toronto, Rotman School of Management, Martin Prosperity Institute, 2015. Available online.

Friesen, Wardlow. 2015. Asian Auckland: The Multiple Meanings of Diversity. Asia New Zealand Foundation, February 2015. Available online.

---. 2019. Quantifying and Qualifying Inequality Among Migrants. In In the Intersections of Inequality, Migration, and Diversification: The Politics of Mobility in Aotearoa/New Zealand, eds. Rachel Simon-Kumar, Francis Collins, and Wardlow Friesen. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gilbertson, Amanda and Carina Meares. 2013. Ethnicity and Migration in Auckland. Auckland Council Technical Report, TR2013/012, February 2013. Available online.

Hayward, Janine. 2012. Biculturalism—Continuing Debates. Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated June 20, 2012. Available online.

Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment. 2018. Migration Trends 2016/2017. New Zealand Government, March 2018. Available online.

---. N.d. Population by Visa Type—Migration Data Explorer. Accessed August 6, 2019. Available online.

Radio New Zealand. 2019. New Residents Down While Temporary Visas Up. Radio New Zealand, July 17, 2019. Available online.

Rahman, Anjum. 2019. Islamic Women’s Council Repeatedly Lobbied to Stem Discrimination. Radio New Zealand, March 17, 2019. Available online.

Simon-Kumar, Rachel. 2014. Neoliberalism and the New Race Politics of Migration Policy: Changing Profiles of the Desirable Migrant in New Zealand. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (7): 1172-91.

---. 2019. Justifying Inequalities: Multiculturalism and Stratified Migration in Aotearoa/New Zealand. In Intersections of Inequality, Migration and Diversification: The Politics of Mobility in Aotearoa/New Zealand, eds. Rachel Simon-Kumar, Francis Collins, and Ward Friesen. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Singham, Mervin. 2006. Multiculturalism in New Zealand: The Need for a New Paradigm. Aotearoa Ethnic Journal 1 (1): 33-37. Available online.

Smith, Philippa. 2016. “New Zealand Passport Holder” versus ”New Zealander?” The Marginalization of Ethnic Minorities in the News: A New Zealand Case Study. Journalism: Theory, Practice, and Criticism 17 (6): 694-710.

Smits, Katherine. 2011. Justifying Multiculturalism: Social Justice, Diversity, and National Identity in Australia and New Zealand. Australian Journal of Political Science 46 (1): 87-103.

Spoonley, Paul. 2015. “I Made a Space for You:” Renegotiating National Identity and Citizenship in Contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand. In Asians and the New Multiculturalism in Aotearoa New Zealand, eds. Gautam Ghosh and Jacqueline Leckie. Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago University Press.

Statistics New Zealand. 2019. Estimated Migration by World Region/Country of Citizenship—International Migration: May 2019. Updated July 15, 2019. Available online.

---. 2019. New Zealand’s Population Grows 1.6 Percent in June Year. News release, August 2019. Available online.

---. N.d. Major Ethnic Groups in New Zealand. Updated January 28, 2015. Available online.

Walker, Ranginui. 1995. Immigration Policy and the Political Economy of New Zealand. In Immigration and National Identity: One People—Two Peoples—Many Peoples? ed. Stuart W. Greif. Auckland: Dunmore Press.