You are here

In Search of Safety, Growing Numbers of Women Flee Central America

A woman walks alongside a train in Mexico. (Photo: Víctor Manuel Espinosa)

Over the past decade, the profile of migrants arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border has gradually—yet dramatically—shifted. Starting around 2014, apprehensions of migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (known as the Northern Triangle of Central America) began to rise, even as reports suggested more Mexican nationals were leaving the United States than arriving. Today, Northern Triangle migrants make up the majority of Southwest border apprehensions, many turning themselves in to authorities to apply for asylum rather than attempting to cross illegally. Several factors that contribute to instability in the region are pushing people to flee in record numbers, resulting in what have been described as refugee-like flows. Entrenched poverty and a desire to reunify with relatives in the United States are also driving some of the migration.

Women and children have proved to be particularly vulnerable to emergent forms of violence and political instability in the Northern Triangle. Since unaccompanied minors began arriving at the U.S. border in startling numbers in 2014, they have justifiably received ample academic and media attention. Yet, there has been less focus on the gendered experiences of women and girls forced to leave the region. Social norms and legal precedent in Northern Triangle countries routinely allow gender-based crimes to go unpunished, and perpetrators of violence act with impunity. Forced recruitment of females to be the girlfriends of gang members (novias de pandillas) and some of the highest femicide rates in the world have produced patterns of behavior and feelings of personal insecurity that directly contribute to women’s decisions to migrate.

The conditions driving this migration did not emerge overnight, rather they are rooted in systemic political and socioeconomic problems. The civil wars that engulfed the Northern Triangle in the latter half of the 20th century resulted in reduced public trust in government and feelings of personal insecurity—fertile ground for gangs, cartels, and other criminal groups. Government institutions are weak, and their territorial control is challenged by these nonstate actors; public-sector corruption is widespread; economies are stagnant, and inequality high; indigenous people are routinely forced off their land; and citizens’ rights are regularly violated.

While women’s migration experiences do not exist in a vacuum separate from those of men, women often face distinct challenges on the journey, in their destination country, during detention, and upon repatriation. This article sketches the expanding representation of Central American women in immigration enforcement activities, illuminates challenges faced by migrant women amid changing U.S. policy, and examines threats upon return to their country of origin. A more holistic evaluation of the migration cycle as seen in the Northern Triangle can serve as a template for understanding mixed-migration flows in other contexts and world regions.

Patterns of Violence

The Northern Triangle countries are home to some of the highest rates of homicide and violent crime in the world, in part the result of ongoing challenges to citizen security and rule of law. Gangs and organized-crime groups rival police and national security forces for territorial control. In El Salvador, the government has reportedly resorted to extrajudicial killings in a failing attempt to quell the two most prominent gangs, Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18. Honduras faces civil turmoil in the wake of what some have deemed a stolen presidential election by incumbent Juan Orlando Hernandez in late 2017. As a result of the influence of gangs and other criminal actors on public institutions, citizens’ trust in law enforcement is low in all three countries, as crimes go unpunished.

While there is no consensus on the root causes driving changes in outflows, violence is a common thread in the stories of people leaving the region, including women. Migration from El Salvador and Honduras is linked to targeted violence—such as murder, kidnapping, extortion, and forced gang recruitment—that produces feelings of personal insecurity. Gang members coerce young women and girls into sexual relationships; resistance can lead to death. Gangs are also known to exact vengeance on rivals via the rape and murder of daughters and sisters.

El Salvador had the third-highest rate of violent deaths of women in the world in 2015, while Honduras ranked fifth. Of the 662 femicide cases opened by the Salvadoran government from 2013 through late 2016, just 5 percent resulted in a conviction. A culture of machismo in Central America helps perpetuate patterns of violence, while leaving women feeling devalued and vulnerable to abuse.

Meanwhile, Guatemalan migration is more often linked to a mix of general violence, poverty, and rights violations, especially among indigenous people. It is difficult to disentangle the exact factors that inspire the ultimate decision to migrate, but it appears that in El Salvador and Honduras the decision is more often the result of immediate threats to safety, while in Guatemala it stems from chronic stressors. Though these generalizations do not hold true in every case, they can serve as useful indicators for better understanding the record number of Central American women migrating to Mexico and the United States.

Growing Apprehensions of Women

Women face extreme hardship on the journey northward, as they experience disproportionately high rates of sexual violence, and can be victimized by actors such as smugglers (coyotes), gangs, cartels, and police. Despite these dangers, growing numbers of Central American women have set off through Mexico in recent years.

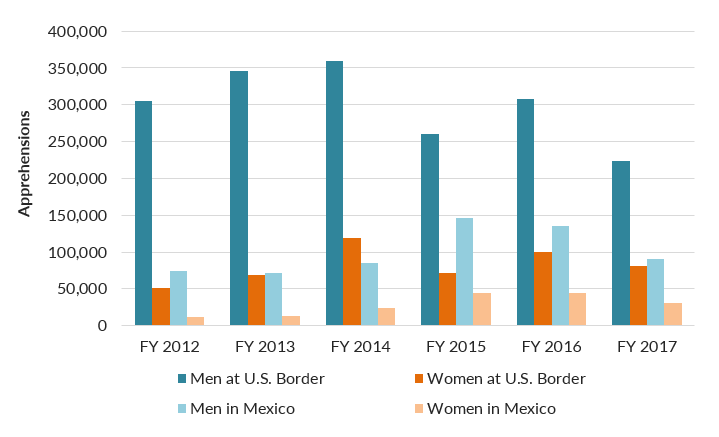

The data clearly show an increase in the share and number of migrant women apprehended in Mexico since fiscal year (FY) 2012. That year, Mexican authorities recorded 11,336 apprehensions of women, constituting 13 percent of the adult total, while in FY 2017 the 30,541 apprehended women made up 25 percent of the total, according to Mexico’s National Migration Institute (INM). Increased female migration from the Northern Triangle and major changes in Mexican immigration enforcement appear to be driving the rise in apprehensions. Overall, migrants from the Northern Triangle have composed the vast majority of border apprehensions in Mexico and the United States in recent years.

Mexico’s Southern Border Program (Programa Frontera Sur), launched in July 2014 by President Enrique Peña Nieto, stepped up Mexican security at the border with Guatemala and Belize and expanded INM’s mandate for interior enforcement. One important result of this policy is that traditional migration routes employed by men are increasingly policed, diverting them to routes and transportation modes typically used by women. These primarily include buses, cars, and cargo trucks on the highways. Border enforcement followed these shifts to the highways, where INM now uses checkpoints to detect the transportation of migrants in vehicles. Together, diverted flows and changed enforcement strategies have increased the likelihood that women will be apprehended.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) data also show increases in the share and number of migrant women taken into custody at the U.S.-Mexico border since FY 2012. Mirroring the uptick in Mexico, the female proportion of adult apprehensions at the border increased steadily from 14 percent in FY 2012 to nearly 27 percent in FY 2017. Girls under age 18 from the Northern Triangle constitute an even greater share of the apprehended child population, at 32 percent in FY 2017.

Figure 1. Adult Apprehensions at the U.S. Southwest Border and in Mexico, by Gender, FY 2012-17

Note: Mexico apprehensions data were converted from calendar year to U.S. fiscal year for comparability.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, “Sector Profile, Fiscal Years 2012-17,” accessed May 11, 2018, available online; and Secretaría de Gobernación, “Boletines Estadísticos, Cuadro 3.1.3, 2011-17,” available online.

In both Mexico and the United States, asylum applications from Central Americans have increased dramatically since 2013, though available data are not disaggregated by sex. Family apprehensions are also up from previous years, with more families traveling together indicating that parents are no longer willing to leave children behind in the country of origin—a departure from past trends.

Experiences in the United States

In the United States, immigrant women in general and unauthorized women in particular (some of whom are Central Americans) have long faced structural disadvantages. Women can experience physical and emotional abuse by partners or employers who use the threat of deportation to exert control over them.

In the workplace, immigrant women are particularly vulnerable to sexual harassment and violence, and many (especially unauthorized women) perceive the legal options available to them to be limited. In some cases, immigrant women—often with the support of local NGOs—have filed lawsuits against their employers, exposing mistreatment. In 2014, Guatemalan farmworker Marlyn Perez sued her employer for withholding paychecks and a company employee for sexually assaulting her. Perez’s story is one among many, and in November 2017 the Alianza Nacional de Campesinas—an organization representing female farmworkers—wrote an open letter calling attention to the sexual assault and harassment women farmworkers experience. The #MeToo movement has exposed how widespread sexual harassment and assault are in various U.S. industries, but their unauthorized status and the threat of deportation add an extra layer of vulnerability for working immigrant women.

New fears of arrest and detention resulting from anti-immigrant rhetoric and changing interior enforcement priorities are also affecting immigrants’ lived experiences, including those of women. Though women have consistently accounted for less than 10 percent of arrests by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and overall arrests by ICE remain below the record level seen during the Obama administration between FY 2009-12, unauthorized immigrants without criminal backgrounds made up a greater share of ICE arrests in FY 2017 than in FY 2015 and 2016. This shift has generated feelings of vulnerability and anxiety about deportation among both authorized and unauthorized migrants, men and women alike.

Unauthorized mothers have reportedly been less willing to walk their children to school or take them for doctor visits as they worry they could be detained while performing otherwise routine care practices. Furthermore, reporting of rapes and domestic violence has fallen among Latino communities in major U.S. cities, and police commissioners in Houston and Los Angeles expressed concern that fear of deportation is deterring victims from reporting crimes. Some 506 pregnant women were detained by ICE between January 1 and March 20, 2018, while during the latter years of the Obama administration, ICE generally released pregnant women pending immigration hearings.

Families under Pressure

Immigrant women in the United States also experience trauma and depression, often the result of being separated from their children. One study found that Mexican mothers separated from all their children were nearly six times more likely to have depression than those with at least one child living with them. Loneliness, social isolation, and dependence on a partner can be exacerbated in communities that do not offer women the opportunity to develop social networks—a factor that is understood to be more important for the positive adjustment of immigrant women than for men. Limited job opportunities with low pay and long hours place further pressure on women, especially mothers, as they simultaneously care for those around them or send money to family in their country of origin. Still, reports indicate that Latina women are willing to remit a greater proportion of their salary and send money more consistently than men.

Even when mothers are reunited with their families, their children often face challenges adjusting to life in the United States. Some Central American youth flee gangs and violence at home only to become recruitment targets for the same gangs—such as MS-13—in the schools and communities where they settle. Once young immigrants arrive, the pressure from gangs, compounded by social isolation and trauma, can push them to join up in a search for purpose and belonging.

Challenges upon Return to the Region

Repatriated men and women face serious threats upon return to the Northern Triangle, including some of the same ones that forced them to flee. Gangs and criminals target deported migrants for extortion, under the assumption they have earned money abroad. Asylum claims based on extortion, harassment, forced recruitment, and death threats are often rejected for not meeting the threshold for credible fear in the United States, prompting deportation of an individual back into the proximity of the person or group that issued the threats. Though the exact figures are unclear, a number of reports have detailed that in the past several years U.S. authorities have increasingly rejected asylum claims, turned away asylum seekers at the border, or ignored legal protections—returning some migrants to unsafe situations in their country of origin.

Returning can be especially dangerous for women. Safehouse operators and lawyers in El Salvador report that returned women are often forced to relocate internally and remain socially anonymous for fear of detection by the gangs or partners they fled. Women fear retribution for leaving abusive relationships or that they may be targeted to deter them from reporting crimes. There have been documented cases of women being revictimized upon return after their asylum cases were rejected.

Women also face the shame of being labeled a “failed” migrant on their return. Public perceptions include viewing returned women as criminals or as sexual deviants who engaged in promiscuity on their migration journey—which, for rape victims, is especially damaging. There is also a common perception that those who return are “bad mothers” who left her children behind. As noted above, families can experience trauma both upon separation and reunification, with children expressing resentment at being left with family or friends. Familial problems can be compounded by changes in standards of living when the mother is returned and the flow of remittances ends.

Over the past several years, there has been a sharp drop in the number and share of deported migrants—and in particular women—who intend to return to the United States. Not surprisingly, deported mothers who have children still living in the United States are more likely to remigrate than those who are not separated from their children. This pattern holds as much for fathers as mothers, meaning that immigration enforcement practices that separate families will likely result in parents migrating once again to reunite with their children.

Bringing Migration Full Circle

Immigrant women from Central America are experiencing changes firsthand amid a shifting enforcement landscape in the United States and Mexico, and narrowing avenues to asylum, while those who are returned face serious challenges often including threats to their safety. Evaluations of the political, social, and economic climate in the Northern Triangle are necessarily incomplete without factoring in the unique experiences of women. A gendered perspective can illuminate how various legal and cultural norms create vulnerabilities that disproportionately affect specific groups.

One clear pattern emerges from studying this migration: Safeguards are lacking to protect women and girls from perpetrators of violence at all phases of their journey. Security improvements, in large part, will ultimately come down to legal and institutional reforms in the Northern Triangle to hold offenders accountable, as well as efforts to deter youth from becoming involved with gangs in countries of origin and the United States. On this latter point, small-scale violence prevention programs in El Salvador have shown promise in reducing levels of violence while increasing positive perceptions of security. Similarly, programs in the United States have yielded promising results for youth who want to cut ties with gangs to focus on their education.

One of the four pillars of the Plan for Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle—a tripartite agreement backed by the United States to reduce migration from the region—is to bolster security and justice for citizens. However, the goals of the plan may be undermined by U.S. policy decisions that threaten social cohesion in Northern Triangle countries. The impending end of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for some 300,000 nationals of El Salvador and Honduras, alongside increasing deportations, could place greater stress on these countries, exacerbating the underlying causes of migration from the region.

Furthermore, providing a more expansive view of the migration cycle can facilitate policy suggestions that help address specific risks and vulnerabilities faced by female migrants at distinct phases of their journey, as well as offer context for how trauma in one stage can influence experiences later on. The migration cycle approach used in this case should not be limited to the Northern Triangle; rather, it can serve as a template for understanding mixed-migration flows in other regional contexts. Meanwhile, a gendered lens can produce insights into frequently overlooked populations, thus expanding the range of viable responses governments and other organizations could use to enhance protections for vulnerable groups.

This article draws from a forthcoming Migration Policy Institute report, The Migration Journeys of Central American Women. The report was supported by the Ford Foundation, through a contract with NEO Philanthropy.

Sources

Abrego, Leisy and Ralph LaRossa. 2009. Economic Well-Being in Salvadoran Transnational Families: How Gender Affects Remittance Practices. Journal of Marriage and Family 71 (4).

American Immigration Council (AIC). 2017. The Impact of Immigrant Women on America’s Labor Force. AIC, March 8, 2017. Available online.

Blitzer, Jonathan. 2016. The Death of Berta Cáceres. The New Yorker, March 11, 2016. Available online.

---. 2018. The Teens Trapped between a Gang and the Law. The New Yorker, January 1, 2018. Available online.

Boehm, Deborah. 2017. Separated Families: Barriers to Family Reunification After Deportation. Journal on Migration and Human Security 5 (2): 401-16.

Brigida, Anna-Cat. 2016. Deporting People to their Doom in Murderous Central America. The Daily Beast, February 7, 2016. Available online.

Call, Charles. 2017. What Guatemala’s Political Crisis Means for Anti-Corruption Efforts Everywhere. Blog post, Brookings Institution, September 7, 2017. Available online.

Capps, Randy, Muzaffar Chishti, Julia Gelatt, Jessica Bolter, and Ariel G. Ruiz Soto. 2018. Revving Up the Deportation Machinery: Enforcement under Trump and the Pushback. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Clemens, Michael. 2017. Violence, Development, and Migration Waves: Evidence from Central American Child Migrant Apprehensions. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. Available online.

Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (COMAR). 2017. Estadísticas, 2013-2017. Available online.

Diaz, Gabriela and Gretchen Kuhner. 2007. Women Migrants in Transit and Detention in Mexico. Migration Information Source, March 1, 2007. Available online.

Dreby, Joanna and Leah Schmalzbauer. 2013. The Relational Contexts of Migration: Mexican Women in New Destination Sites. Sociological Forum 28 (1).

Dreby, Joanna. 2012. The Burden of Deportation on Mexican Immigrant Families. Journal of Marriage and Family 74.

El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (COLEF). 2015. Encuesta Sobre Migración en la Frontera Norte de México (EMIF Norte). Tijuana, Mexico: COLEF. Available online.

Gonzalez-Barrera, Ana. 2015. More Mexicans Leaving Than Coming to the U.S. Pew Research Center, November 19, 2015. Available online.

Gutierrez Vazquez, Edith Y., Chenoa A. Flippen, and Emilio A. Parrado. 2015. Feeling Depressed in a Foreign Country: Mental Health Status of Mexican Migrants in Durham, NC. Paper presented at Population Association of America 2015 Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, April 30-May 2, 2015. Available online.

Hurtado-de-Mendoza, Alejandra, Adriana Serrano, Felisa Gonzales, and Stacey Kaltman. 2014. Social Isolation and Perceived Barriers to Establishing Social Networks Among Latina Immigrants. American Journal of Community Psychology 53: 73-82.

Husain, Alina and Leslye Orloff. 2015. Immigrant Women, Work, and Violence Statistics. National Immigrant Women's Advocacy Project, American University, June 19, 2015. Available online.

International Crisis Group. 2016. Easy Prey: Criminal Violence and Central American Migration. New York: International Crisis Group. Available online.

Kassam, Ashifa. 2017. Guatemalan Women Take on Canada's Mining Giants over “Horrific Human Rights Abuses.” The Guardian, December 13, 2017. Available online.

Kennedy, Elizabeth. 2017. Forced to Flee: Responding to the Humanitarian Crisis in Central America. Remarks at panel event, Doctors Without Borders, November 14, 2017. Available online.

Leutert, Stephanie and Caitlyn Yates. 2017. Migrant Smuggling Along Mexico’s Highway System. Austin, Texas: University of Texas-Austin, Strauss Center’s Mexico Security Initiative, November 2017. Available online.

Lewis, Brooke. 2016. HPD Chief Announces Decrease in Hispanics Reporting Rape and Violent Crimes Compared to Last Year. Houston Chronicle, April 6, 2016. Available online.

Lorenzen, Matthew. 2017. The Mixed Motives of Unaccompanied Child Migrants from Central America’s Northern Triangle. Journal on Migration and Human Security 5 (4): 744-67.

Miguel Cruz, Jose. 2017. How Political Corruption Fuels Gang Violence in Central America. Pacific Standard, October 24, 2017. Available online.

Miller, Michael E. 2017. She Thought She’d Saved Her Daughter from MS-13 by Smuggling Her to the U.S. She Was Wrong. Washington Post, March 20, 2017. Available online.

Miller, Michael E. and Dan Morse. 2017. “People Here Live in Fear”: MS-13 Menaces a Community Seven Miles from the White House. Washington Post, December 20, 2017. Available online.

Mossaad, Nadwa and Ryan Baugh. 2018. Refugees and Asylees: 2016. Washington, DC: Department of Homeland Security. Available online.

O’Toole, Molly. 2018. El Salvador’s Gangs Are Targeting Young Girls. The Atlantic, March 4, 2018. Available online.

Paris-Pombo, Maria Dolores and Diana Carolina Pelaez-Rodriguez. 2015. Far from Home: Mexican Women deported from the U.S. to Tijuana. Journal of Borderlands Studies 31 (4): 551-61.

Quinn, Cameron and John Roth. 2017. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Detention and Treatment of Pregnant Women. Letter to Department of Homeland Security, September 26, 2017. Available online.

Raderstorf, Ben, Carole J. Wilson, Elizabeth J. Zechmeister, and Michael J. Camilleri. 2017. Beneath the Violence: How Insecurity Shapes Daily Life and Emigration in Central America. Washington, DC: The Dialogue and Latin American Public Opinion Project. Available online.

Ramchandani, Ariel. 2018. There's a Sexual-Harassment Epidemic on America’s Farms. The Atlantic, January 29, 2018. Available online.

School of International Studies Task Force. 2017. The Cycle of Violence: Migration from the Northern Triangle. Seattle, WA: University of Washington. Available online.

Secretaría de Gobernación (SEGOB). Various years. Boletines Estadísticos, Cuadro 3.1.3, 2011-17. Available online.

Secretaría General del Sistema de la Integración Centroamericana (SICA). 2016. Factores de Riesgo y Necesidades de Atención para las Migrantes Mujeres en Centroamérica. La Libertad, El Salvador: SICA. Available online.

Stillman, Sarah. 2018. When Deportation is a Death Sentence. The New Yorker, January 15, 2018. Available online.

TIME. 2017. 700,000 Female Farmworkers Say They Stand with Hollywood Actors against Sexual Assault. TIME, November 10, 2017. Available online.

Townsend, Mark. 2018. Women Deported by Trump Face Deadly Welcome from Street Gangs in El Salvador. The Guardian, January 13, 2018. Available online.

Trull, Armando. 2017. Rescued from a Gang: One Maryland Latina’s Story. WAMU, April 10, 2017. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2015. Women on the Run. Washington, DC: UNHCR. Available online.

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). 2014. Impact Evaluation of USAID’s Community-Based Crime and Violence Prevention Approach in Central America: Regional Report for El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Panama. Washington, DC: USAID and Vanderbilt University. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Various years. Sector Profiles, Fiscal Years 2012-17. Available online.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Refugee Resettlement. 2018. Unaccompanied Children’s Services: Facts and Data. Available online.

Widmer, Mireille and Irene Pavesi. 2016. A Gendered Analysis of Violent Deaths. Geneva: Small Arms Survey. Available online.