You are here

Legal Snags and Possible Increases in Border Arrivals Complicate Biden’s Immigration Agenda

President Joe Biden signs executive orders on immigration in the White House. (Photo: Adam Schultz/White House)

Though eager to move on from the policies of its predecessor, President Joe Biden’s administration is facing challenges enacting its immigration enforcement agenda, both in the interior and at the U.S.-Mexico border. Court injunctions, administrative resistance, and novel bureaucratic hurdles put in place by the Trump administration shortly before its end, as well as mounting pressures at the southwest border, have complicated the Biden administration’s efforts to roll back the Trump legacy. Though Biden’s presidency is still in its infancy and leaders have yet to be confirmed at some agencies with key roles in the immigration system, these challenges demonstrate the difficulties of achieving quick results that some of his supporters had taken for granted.

The Biden team began with an ambitious plan to soften some elements of the enforcement-first approach that characterized the Trump administration. In the interior, it established a 100-day moratorium on most deportations while it worked on a review of policies for the longer term and issued interim guidelines with narrowed immigration enforcement priorities. At the border, it has temporarily kept intact the Trump administration policy that permits expulsions of almost all border crossers, while also ending the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP, also known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy) and working to develop a revised system to receive and process new asylum seekers.

The administration has advanced some elements of its agenda, but the challenges of redirecting the enforcement apparatus, the tangled web of legal agreements signed by prior Department of Homeland Security (DHS) leadership, and anxieties about a new large-scale influx of migrants and asylum seekers have posed early challenges.

Narrowing Interior Enforcement, but Not Without Stumbles

On Inauguration Day, DHS issued a 100-day freeze on deportations, with narrow exceptions for noncitizens believed to pose threats to national security as well as those who entered the United States on or after November 1, 2020, who waived their rights to remain, or whose removal was required under law. The moratorium was immediately challenged by the state of Texas and subsequently temporarily blocked by a federal judge within a week, then indefinitely halted by a preliminary injunction on February 23. U.S. District Judge Drew Tipton of the Southern District of Texas found that the pause in deportations likely violated a statutory requirement that noncitizens with final removal orders be removed within 90 days, and was likely arbitrary and capricious under the Administrative Procedures Act because DHS failed to provide a sufficient explanation for the new policy.

Still, the administration has imposed constraints on some removals. For example, on February 3 a flight carrying Angolan, Cameroonian, and Congolese deportees was cancelled at the last minute to allow those on board to be interviewed as part of an investigation of alleged assault by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents. Such last-minute holds on deportations of potential witnesses are not themselves a change; the Trump administration, for example, pulled several witnesses off a flight in November 2020 during an investigation into alleged sexual assault by an ICE-contracted gynecologist. But that happened only after lawmakers and the witnesses’ lawyers intervened in the cases. The February 3 flight suspension, on the other hand, was pursuant to internal agency instructions and could indicate a high-level agency review.

Enforcement Guidelines Represent Narrowest Focus in Years

Adjustments to DHS enforcement priorities are critical in carrying out Biden’s agenda in the long run. New interim priorities went into effect February 1, were amended and operationalized with a February 18 memorandum, and will remain in place until DHS completes a review of its enforcement policies and issues final guidelines (expected before the end of May). The priorities set out whom U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) targets for arrest and detention as well as to whom it might grant discretionary relief in removal proceedings. ICE’s new guidelines thus promise that fewer noncitizens will be apprehended and placed in the removal system, instead of just focusing on removals, as the moratorium did.

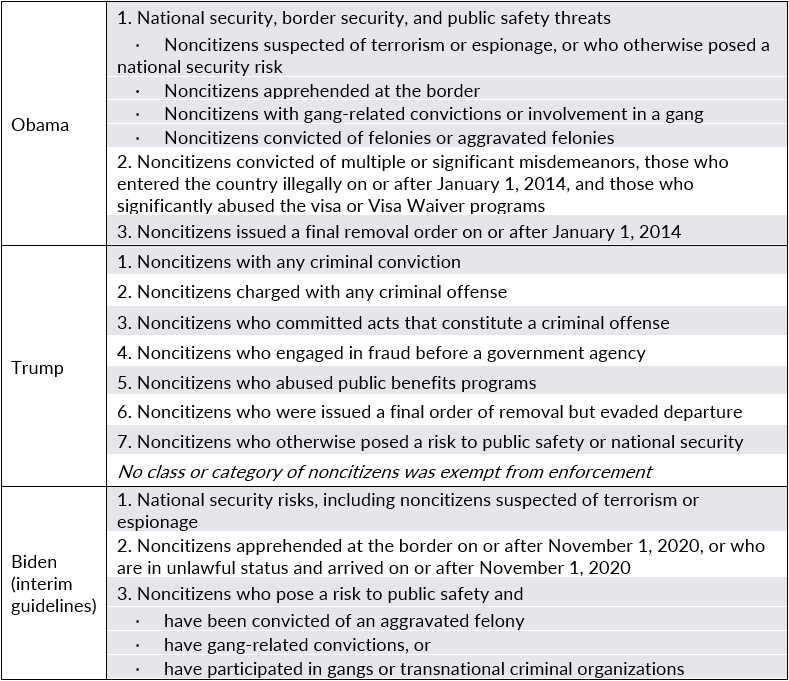

The February 18 interim guidelines, although slightly broader than those that the Biden administration initially put into effect, represent the narrowest enforcement priorities that have been implemented in recent years (see Table 1). They ensure that the overwhelming majority of unauthorized immigrants are not a priority for arrest and removal, as was the case toward the end of the Obama administration. The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) has estimated that 87 percent of the unauthorized population was not a target for enforcement under the 2014 enforcement guidelines, which were later reversed by the Trump administration. That share remains at least as high under the interim Biden priorities.

Table 1. Interior Immigration Enforcement Priorities under Presidents Obama, Trump, and Biden

Sources: Memorandum from Jeh Charles Johnson, Secretary of Homeland Security, to Thomas S. Winkowski, Acting Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); R. Gil Kerlikowske, Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP); Leon Rodriguez, Director, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS); and Alan D. Bersin, Acting Assistant Secretary for Policy, Policies for the Apprehension, Detention and Removal of Undocumented Immigrants, November 20, 2014, available online; Memorandum from John Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security, to Kevin McAleenan, Acting Commissioner, CBP; Thomas D. Homan, Acting Director, ICE; Lori Scialabba, Acting Director, USCIS; Joseph B. Maher, Acting General Counsel; Dimple Shah, Acting Assistant Secretary for International Affairs; and Chip Fulghum, Acting Undersecretary for Management, Enforcement of the Immigration Laws to Serve the National Interest, February 20, 2017, available online; and Memorandum from Tae D. Johnson, Acting Director, ICE, to All ICE Employees, Interim Guidance: Civil Immigration Enforcement and Removal Priorities, February 18, 2021 available online.

Yet there are instances where, despite the new guidelines, enforcement has gone forward against noncitizens who would appear to be lower priorities. Since Biden took office, a witness in the case against the alleged perpetrator of the 2019 shooting that killed 23 people at an El Paso Walmart was deported to Mexico, and a stateless man was deported to Haiti despite the intervention of lawmakers and advocates. Members of the Congressional Black and Hispanic Caucuses have called on the Biden administration to rein in deportations of people who may face dangerous conditions in their countries of origin, including Haiti and Cameroon, and adhere to the new enforcement priorities. These instances—while not violations of the February 1 enforcement guidelines in effect at the time, which allowed agents to use their discretion to conduct enforcement outside the stated priorities—demonstrate the disconnect between the president’s agenda and ICE practices, and the difficulty of dramatically and instantaneously reorienting the culture of an agency that had previously been encouraged to maximize enforcement at all costs and does not yet have a Biden-appointed director in place.

Notably, the updated February 18 guidelines do not allow agents to exercise such broad discretion, requiring agents to get preapproval from their field office directors to conduct non-priority enforcement actions. And even with these highly visible examples of enforcement that may be at odds with the goals of the Biden administration, preliminary ICE data indicate that in the first two weeks of February, detention of noncitizens arrested by ICE were occurring at roughly half the rate as in January. While the new enforcement strategy may not yet be universally followed, these initial data show they are likely having a real effect.

Trump Administration Obstacles to Biden’s Changes

Though the new enforcement guidelines have escaped legal challenge thus far, the rapid litigation over the deportation freeze is evidence that many of the Biden administration’s policy changes will be challenged in court, continuing a trend of increased and multipronged immigration litigation. This trend started in the Obama administration, with the number of immigration lawsuits spiking during Trump’s presidency. The University of Michigan’s Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse catalogued 122 immigration or border-related lawsuits filed during Obama’s eight years in office, compared to 333 during the four-year Trump term.

Trump administration officials seeded their own legal maneuvers to make it more difficult for the Biden administration to implement its agenda. Two of these actions were the unprecedented agreements signed by Ken Cuccinelli, who at the time was the senior official performing the duties of the deputy secretary of Homeland Security, with at least four states and one local sheriff’s office, and with the union representing 7,600 ICE employees, the National ICE Council, in the final two weeks of the Trump presidency.

The agreements with the states and locality—Arizona, Indiana, Louisiana, Texas, and the sheriff’s office in Rockingham County, North Carolina—are known as Sanctuary for Americans First Enactment (SAFE) agreements. Although not all have been made public, those that have require DHS to notify the states six months in advance of any policies that would reduce immigration enforcement or relax the standards for granting relief from deportation, review states’ feedback on the proposed policy changes, and, if the department chooses not to accept the response, provide an explanation. The Texas lawsuit challenging the deportation moratorium argued that DHS had violated this agreement, but the judge declined to take a position on that question even as he accepted the challenge on other grounds. On February 2, DHS notified Texas that it would terminate the agreement immediately, though the text requires 180 days’ notice.

These agreements effectively give the signatories unprecedented power over immigration policy, furthering what has been an ongoing partisan divide between states and the federal government over the issue. This divide has deepened over the past decade as state attorneys general—both Republicans and Democrats—have taken a more activist stance in challenging federal immigration policy and asserting a bigger role in making their own local policies that affect immigration enforcement.

The agreement with the ICE union, signed the day before Trump left office, gave the union broad powers to delay ICE policy changes. DHS disapproved the agreement on February 16, within its 30-day period for review, thereby preventing it from being implemented. Had the deal gone into effect, ICE would have had to work with the union to agree on the terms of any policy changes prior to implementation. There remains the possibility that the union, which endorsed Trump’s presidential campaigns, could appeal the rejection of the agreement to the Federal Labor Relations Authority.

These agreements may initially impede the Biden administration’s policymaking, but they are unlikely to survive court challenges. And though the deportation moratorium—Biden’s most symbolic interior enforcement effort—has been halted in its tracks, other longer-lasting policies such as the narrower enforcement guidelines so far have proceeded unchallenged.

Continuity of Border Enforcement in the Face of Possible Increases in Arrivals

Despite its hopes for a slower pace of border crossings, the Biden administration is facing signs that suggest increased arrivals may be forthcoming. In January, there were 75,000 interceptions of migrants at the southwest border, outpacing every January since 2006. And the number of migrants traveling as families apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border increased 62 percent from December to January, one of the biggest month-to-month increases since 2014, indicating that arrivals may be growing rapidly. Though many of these incidents may have been of the same people trying to cross multiple times—DHS has acknowledged that 38 percent of those encountered between March 2020 and February 2021 had tried to enter before in the same year, up from 7 percent in fiscal year 2019—anecdotal reports indicate the number of fresh arrivals is increasing as well.

The administration has kept in place the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) order issued in March 2020 allowing the United States to expel almost everyone who crosses the border illegally without giving them the opportunity to seek asylum or other relief. In addition to continuing public-health concerns surrounding COVID-19, maintaining the order was meant to deter a predicted surge of migrants trying to reach the United States after Biden’s inauguration, on the theory that his administration would relax border enforcement. Biden himself warned against such a surge, and his spokeswoman argued that the new administration needed time to put in place a fairer and more efficient asylum system at the border. “Asylum processes at the border will not occur immediately; it will take time to implement,” White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said in mid-February.

Still, the administration has made some exceptions under circumstances that remain unclear. In late January, some migrant families apprehended along certain border sectors began to be released to U.S. communities rather than expelled to Mexico under the CDC order. This may be due to at least two factors: increased space restrictions in U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) holding facilities due to COVID-19 protocols and Mexican localities’ refusal to accept expelled families due to a new law prohibiting holding migrant children in detention. However, the Biden administration has not communicated exactly where and under what circumstances it is releasing families into U.S. communities, and it is unclear whether they are part of a pattern or are policy exceptions. The administration also declared it will not expel unaccompanied children under the CDC order, in a switch from the Trump era. But it is not moving fast enough for some: in late February, 61 Democratic House members sent a letter to Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas urging him to end all expulsions under the order “as soon as practicable.”

A Slow End to Remain in Mexico

Unlike its tinkering around the edges of the CDC order, the administration has begun to roll back some of the most restrictive policies of the Trump administration. It started with ending MPP, announcing a process for those enrolled in the program with open immigration court cases to enter the United States. However, MPP enrollees allowed back into the United States through this system are not processed in special courts empaneled to hear their asylum claims, but funneled into the same immigration court backlogs that have been plaguing the system for years. Of course, there are arguments for moving swiftly: the population waiting in Mexico under MPP is one of the most vulnerable and Biden had promised to end the program as one of his first actions. But the administration has done so without also creating a dedicated system to process the asylum cases of recent border crossers. This could incentivize increases in flows.

Finally, Biden has ended policies that the Trump administration enacted in 2019 and paused during the pandemic, including the Asylum Cooperation Agreements with El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, which allowed U.S. asylum seekers arriving at the border to be sent to seek asylum in those countries, as well as implementation of two rapid asylum adjudication programs: the Prompt Asylum Claim Review program and the Humanitarian Asylum Review Process. Both sets of policies blocked access to U.S. territory and the asylum system. Ending these programs has no effect in practice while the CDC order remains in place, since the public-health rule blocks access to the U.S. asylum system more broadly. But once it is lifted, these policies will not encumber the new administration’s intended border policies. And while the administration has not yet begun the process of revoking the regulation making ineligible for asylum anyone who had traveled through a third country before reaching the U.S.-Mexico border without seeking and being denied asylum there, a federal judge preliminarily blocked it on February 16, and the government is likely to choose not to continue defending it in court.

Once the CDC order is lifted, none of the Trump policies that explicitly blocked access to the asylum system for border crossers will remain. Still, the narrower grounds on which asylum can be granted that were enacted during the Trump administration will continue to apply in proceedings before immigration courts.

In all, Biden’s administration has dismantled critical elements of Trump’s strictest policies on illegal border crossings and is adjusting the implementation of those that remain. It continues to face the challenge of building an asylum processing system that provides quick protection to those who qualify and humanely returns those who do not, without applicants spending years in the immigration court backlogs.

Such much-needed reform of the asylum system could be frustrated by large border arrivals in coming weeks and months, although over the long term the administration has committed to countering these types of movement with a greater attention to root causes of migration and a regional migration management system. And in the interior of the country, the administration is still struggling to wrap its arms around the enforcement machinery that was left to run at full steam and without guardrails under Trump, creating a climate of fear that overshadowed its mixed results because of pushback from state and local jurisdictions. The Biden administration’s supporters have been eager to see a sharp reversal of the policies of the Trump era, but the realities at the border and the impediments to advancing Biden’s enforcement agenda in the interior suggest the need for a long-term plan.

Sources

Aleaziz, Hamed. 2021. The DHS Has Signed Unusual Agreements with States That Could Hamper Biden’s Future Immigration Policies. BuzzFeed News, January 15, 2021. Available online.

Borger, Julian. 2021. Exclusive: ICE Cancels Deportation Flight to Africa After Claims of Brutality. The Guardian, February 4, 2021. Available online.

Carrasquillo, Adrian. 2021. Black, Hispanic Caucuses Apply Pressure to Biden to Reign in ICE, Deportations. Newsweek. February 11, 2021. Available online.

Charles, Jacqueline. 2021. He Wasn’t Born in Haiti. But That Didn’t Stop ICE from Deporting Him There, Lawyer Says. Miami Herald, February 2, 2021. Available online.

Flores, Adolfo and Hamed Aleaziz. 2021. Border Agents in Texas Have Started Releasing Some Immigrant Families after Mexico Refused to Take Them Back. BuzzFeed News, February 5, 2021. Available online.

Gamboa, Suzanne and Associated Press. 2021. ICE Defies Biden, Deports El Paso Massacre Witness, Hundreds of Others. NBC News, February 2, 2021. Available online.

O’Toole, Molly. 2020. ICE Is Deporting Women at Irwin Amid Criminal Investigation into Georgia Doctor. Los Angeles Times, November 18, 2020. Available online.

Rose, Joel. 2020. Immigrant Advocates Vow to Keep Up the Pressure as Biden Asks for Patience. NPR, December 23, 2020. Available online.

Sganga, Nicole and Camilo Montoya-Galvez. 2021. Homeland Security Officials Scrap Trump-Era Union Deal that Could Have Stalled Biden's Immigration Policies. CBS News. February 16, 2021. Available online.

State of Arizona and Mark Brnovich v. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, et al. 2021. U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona, Exhibit C. February 3, 2021. Available online.

State of Texas v. United States, et al. 2021. U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas, Exhibit A. January 22, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas, Order Granting Plaintiff’s Emergency Application for a Temporary Restraining Order. January 26, 2021. Available online.

University of Michigan Law School. N.d. Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse. Accessed February 19, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2021. Notice of Temporary Exception from Expulsion of Unaccompanied Noncitizen Children Pending Forthcoming Public Health Determination. Federal Register 86 (30), February 17, 2021: 9942. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). 2021. Southwest Land Border Encounters. Updated February 10, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2021. DHS Announces Process to Address Individuals in Mexico with Active MPP Cases. News release, February 11, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Letter from David P. Pekoske, Acting Secretary of Homeland Security, to Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton. February 2, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Memorandum from David Pekoske, Acting Secretary of Homeland Security, to Troy Miller, Senior Official Performing the Duties of the Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection; Tae Johnson, Acting Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; and Tracey Renaud, Senior Official Performing the Duties of the Director, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Review of and Interim Revision to Civil Immigration Enforcement and Removal Policies and Priorities. January 20, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). 2021. Memorandum from Tae D. Johnson, Acting Director of ICE, to All ICE Employees, Interim Guidance: Civil Immigration Enforcement and Removal Priorities. February 18, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and ICE Council 118, American Federation of Government Employees. 2021. Memorandum of Agreement. January 19, 2021. Available online.

White House. 2021. Press Briefing by Press Secretary Jen Psaki. February 10, 2021. Available online.

Wilson, Frederica. 2021. Twitter post. February 23, 2021. Available online.