You are here

Spike in Unaccompanied Child Arrivals at U.S.-Mexico Border Proves Enduring Challenge; Citizenship Question on 2020 Census in Doubt

Border Patrol agents inspect child migrants in El Paso, Texas (Photo: U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

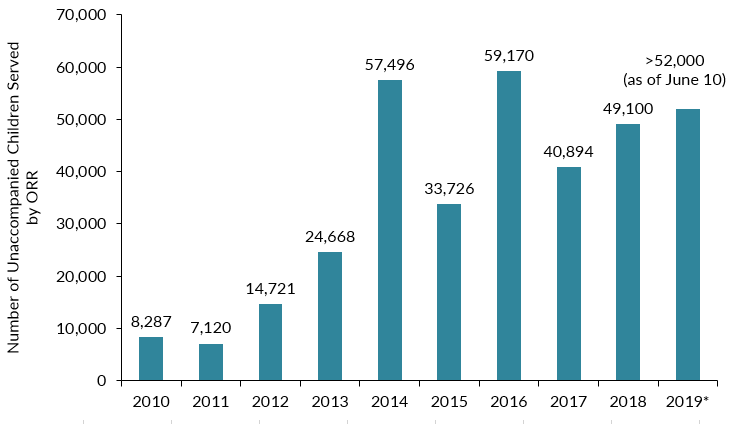

With the apprehension of 11,500 Central American unaccompanied children at the U.S.-Mexico border in May alone, this fiscal year is on track to far exceed the numbers seen during fiscal 2014, when the surge in arrivals of these minors was viewed as a crisis. The care of these children, whether in initial detention at the border or later government custody, has provoked growing public outrage—in particular with reports in recent days of unsafe, filthy conditions that children, including infants, have experienced in overcrowded Border Patrol holding facilities.

The outcry is reminiscent of the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance policy that resulted in the separation of thousands of migrant children from their parents, in hopes of deterring the growing numbers of family arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border. Even as that policy was shelved in June 2018 amid major national and international outcry, more than 700 children have been separated from their parents since then.

While the apprehension of “family units” (the government’s term for family members traveling together) has outpaced the arrival of unaccompanied minors in recent years, the surge in child arrivals has risen to new levels this year. This record flow has overwhelmed normal government responses, with cascading negative and even deadly consequences. The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR)—the arm of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) that takes custody of the children and is responsible for their care—has run acutely short of funds and bed space, and predicts it will exhaust its funding before the end of the month. Amid these challenges, the government has canceled educational and recreational activities for the children, erected tent cities in the desert to hold them, and contemplated housing some on military bases.

The lack of beds in ORR facilities has created deplorable conditions at the border, with children subjected to waits of days and weeks at crowded U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) facilities that were never intended to house minors. As CBP grapples with the overcrowding, government lawyers unapologetically argued before the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals last week that the administration had no obligation to provide children with beds, soap, or toothbrushes. During the last year, seven immigrant children have died after or while being detained at CBP facilities.

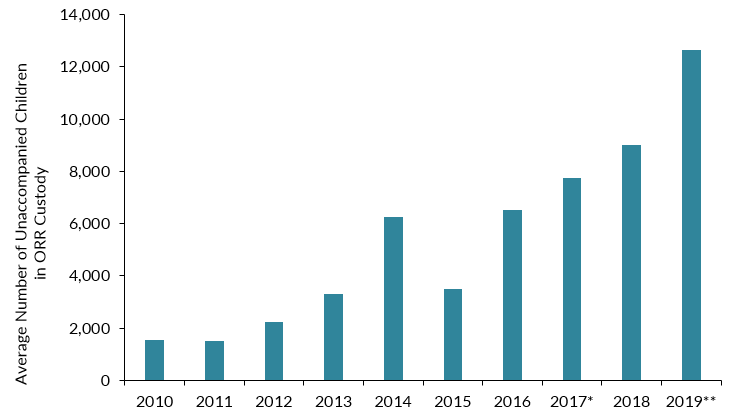

While the administration is blaming Congress for delays in approving more than $4 billion in new spending to address conditions at the border, the funding and overcrowding crisis it faces is partly of its own making. The administration failed to ask for an increase in funds in its fiscal year (FY) 2019 budget request despite projecting more unaccompanied minors would arrive during the year. And its decision to share information ORR gathers about potential sponsors of unaccompanied children with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) drove up the length of time children spend in ORR custody. In December 2018, nearly 15,000 children were held in custody—a historic high. As of April, the number has fallen to 12,587, but has required ORR to turn, in some cases, to costly emergency shelters run by private contractors.

The continuing rise in child arrivals—just as during the 2014 surge—offers a constant reminder that this migration pattern is unlikely to abate and should be seen as an ongoing phenomenon instead of an occasional episodic crisis. The failure of both the Trump and Obama administrations and Congress to plan for this reality has severely undermined the government’s ability to build a sustained capacity response with built-in flexibility to accommodate the ups and downs of migrant flows. The lack of such capacity precipitates crises leading to conditions of the kind witnessed in recent weeks—in which children are subjected to wait for weeks at ill-prepared and unsanitary Border Patrol facilities. Attorneys visiting one Border Patrol facility in Clint, Texas, last week reported seeing toddlers without diapers, children unbathed and wearing the same clothes for weeks at a time, and many sick with the flu.

As the media continues to report on these conditions in CBP facilities, the House and Senate as of this writing had passed separate bills providing about $4.5 billion in emergency funding for the agencies dealing with the border crisis—though lacked consensus on a final package. However this funding debate turns out, there is still no sign of a real commitment to a long-term solution for sustained capacity building for the care of unaccompanied children.

Arrivals Swell Amid New Enforcement Actions

So far this fiscal year, CBP has apprehended 56,278 unaccompanied children crossing the U.S. border illegally, in addition to 3,236 others arriving at ports of entry. Under the 2008 Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA), Central American unaccompanied minors who arrive at the U.S. border may not be immediately deported. Instead, they are given the opportunity to present their claim for asylum under U.S. law and are transferred to the care and custody of ORR. The agency is then obligated to try to find family members or other sponsors in the United States to whom the children could be transferred. If no such sponsors are found, the children stay in ORR custody.

The Trump administration’s targeting of sponsors has caused the population in custody to swell. In April 2018, the administration adopted a new policy toward potential sponsors: it began sharing the fingerprints of potential sponsors—and all members of their household—with ICE, resulting in the arrest of some sponsors who were unauthorized immigrants. By December 2018, 170 potential sponsors had been arrested, 109 of whom had no criminal record.

These actions evidently created a chilling effect and offers of potential sponsorship dropped. Children were spending an average 93 days in custody as of November 2018, up from 34 days in FY 2016. After the daily population in custody surged, in a reversal, ORR in December 2018 announced it would no longer fingerprint all adults in the households of potential sponsors.

Figure 1. Average Number of Unaccompanied Minors in Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) Custody, FY 2010-19*

* The average number of children in care for fiscal year (FY) 2017 is unavailable, so the displayed number represents an average between 2016 and 2018 numbers.

** Data for FY 2019 are through April 2019.

Sources: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), “Annual ORR Reports to Congress” (several years), accessed June 25, 2019, available online; ORR, “Latest UAC Data – FY2018,” updated May 6, 2019, available online; ORR, “Latest UAC Data – FY2019,” updated May 30, 2019, available online.

Congress also stepped in to restrict enforcement actions against sponsoring families. In a February 2019 appropriations bill, Congress conditioned that no funds be used to detain, remove, or begin removal proceedings against any sponsor based on information ICE received from ORR. Perhaps as a result of this change, according to the most recently available numbers, the average time in ORR custody dropped to 48 days in April.

But with a still near-historical high of more than 14,000 children in its custody, ORR has told Congress that funding for migrant child care will run out entirely before July. Congress was alerted to the funding shortage in March, when then-Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen cautioned in a letter that ORR was hitting “peak capacity.”

To deal with the rising numbers, during the last year ORR has operated two influx facilities: Homestead Job Corps Facility in Homestead, Florida and Tornillo in El Paso, Texas. Together, these facilities can house a maximum of 7,000 children. The cost of housing unaccompanied minors in such temporary shelters is three times higher than in regular ORR shelters, because of the need to quickly develop the facilities and hire significant staff. Tornillo was operational for only six months, from June 2018 to January 2019, and cost the U.S. government more than $430 million.

The large number of children in care—and the use of expensive temporary housing—has exacerbated a funding crisis that was all but inevitable from the outset. ORR failed to request sufficient funds upfront. In its budget request for FY 2019, ORR planned for a peak population of 9,000 child migrants. Yet at the time this request was made, in February 2018, the population in care already exceeded 7,600, offering hints that the 9,000 would be insufficient. So far in FY 2019, the monthly average number of children in ORR care has never gone below 11,000.

Even before FY 2019 started, in September 2018, HHS notified Congress that to pay for the increased child housing costs, it intended to transfer up to $186 million from funds allocated to other HHS programs, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Medicare and Medicaid, and the National Institutes of Health.

The shortfall has begun to have serious implications for the health and wellbeing of the children. On May 30, HHS ended educational and recreational activities, telling service providers that federal funds released on or after May 22 could only be used for activities “directly necessary for the protection of life and safety.”

A History of Surges and Funding Problems

While some of the administration’s actions have uniquely exacerbated the current crisis, many of the contributing factors, including insufficient funding and the reliance on expensive temporary housing, have been persistent problems.

ORR first saw a significant increase in child arrivals in FY 2012, when the agency received almost 7,200 referrals during a five-month period—surpassing the prior year’s total arrivals. By the end of the fiscal year, the program had received more than double the number in FY 2011 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Total Number of Unaccompanied Minors Served by the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), FY 2010-19*

Note: The FY 2019 number is as of June 10, 2019.

Sources: ORR, “Annual Report to Congress” (several years), accessed June 25, 2019, available online; HHS and U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Letter to Congress,” June 12, 2019, available online.

To meet the new demand, ORR quickly increased capacity in five emergency reception centers, including Lackland Air Force Base in Texas, and in its permanent shelters. Despite these expansions, many children were detained in gyms and other warehouse-like structures while they awaited vacancies in ORR facilities. To pay for this housing scramble, the Obama administration and Congress transferred funding from other HHS programs, including reimbursement assistance for refugees, national centers for early childhood training and technical assistance, and a social services grant program that normally provides assistance for programs such as foster care and protective services.

Separately, the Obama administration began streamlining the sponsor reunification process. In 2013, when it confronted another rise in unaccompanied child arrivals, ORR discontinued the practice of fingerprinting certain potential sponsors and dropped other screenings. These efforts successfully reduced the average number of days children spent in custody: from 72 in 2011 to less than 35 days in 2014.

However, in 2014, ORR received 57,496 referrals; more than double the amount from the year before and nearly four times as many as during 2012. To accommodate this growing population, the government used three Defense Department facilities: Fort Sill in Oklahoma, Naval Base Ventura County in California, and Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio.

To address the urgent situation, President Obama asked Congress for an additional $3.7 billion, $1.8 billion of which would be used for housing the children in ORR custody. However, the Republican-led Congress conditioned its support on amending the 2008 TVPRA, which it blamed for creating the crisis, and the funds were ultimately never approved. Absent these funds, ORR once again relied on internal funding transfers to make up the difference.

Even though ORR’s streamlining of the sponsor reunification process successfully reduced time spent by children in custody—and thus costs—the efforts were called into question when some exploitative sponsors were exposed. At the end of 2014 it came to light that six Guatemalan youths had been trafficked to an Ohio egg farm where they were forced to work 12 hours a day and threatened with death if they complained. Following an investigation and congressional pressure, ORR reversed some of its sponsor reunification streamlining policies: for example, the agency increased vetting and checks on unrelated family friends who stepped forward to sponsor children.

Despite these repeat upticks in arrivals and patchwork funding solutions, the executive branch and Congress collectively have failed to establish a system that can respond to sizeable fluctuations in capacity demands. The need for such capacity is apparent—the average daily population of unaccompanied children in ORR custody in 2015 varied dramatically from under 2,500 to close to 6,000.

Beginning in 2015, the Obama administration annually petitioned Congress for a contingency fund to provide ORR with additional funding to accommodate higher-than-expected caseloads. And Congress every year denied the request. This pattern continues under the Trump administration. In its FY 2020 request, the administration requested a contingency fund capped at $2 billion over three years.

Other than the repeated request for this contingency fund, there has been no acknowledgment that the unaccompanied minors present an enduring crisis. The Trump administration has adopted even more hardline policies against unaccompanied children (see box). These policies are ostensibly intended to deter children from coming to the United States in the future. However, there is little evidence that such policy changes will affect the rising numbers. The challenge of child arrivals is just one facet of the broader asylum crisis that the Central American migrant flows present. Implementing punitive policies against this population to send a message is unlikely to deter these flows. Instead, these measures will only increase the program’s crippling capacity challenges and continue to subject migrant children to precarious conditions.

Box 1: Policies Toward Unaccompanied Children Under the Trump Administration

- Seeing the unaccompanied child program as a driver of migration, the Trump administration has sought to reduce the number of children qualifying for care by the Office of Refugee Resettlement. In a September 2017 legal opinion, the Justice Department took the position that an immigration judge can rescind the unaccompanied child designation during the minor’s court proceedings, if he or she ages out or has been reunified with a parent or legal guardian. Removing the designation would disqualify the child from applying for asylum directly before U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). According to press reports, later this month USICS asylum officers will also begin removing the designations from children whose cases they are adjudicating.

- The administration has also clamped down on another common form of immigration relief for children: Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status. In the first half of 2018, USCIS began systematically denying applications for SIJ status when the applicant is 18 or older.

- In August 2017, ORR began placing all unaccompanied children with any gang-related history in staff secure facilities and made them ineligible for release. The non-release policy was later enjoined by a federal judge.

- According to reports, the administration has also begun immediately transferring unaccompanied children from ORR to ICE custody on their 18th birthdays, the first day on which they no longer meet the statutory definition for ORR care.

Resources

- Latest HHS data on unaccompanied children in care

- 2019 Letter of Homeland Security Secretary to Congress on the southern border crisis

- HHS FY 2020 Budget Justification

- Houston Chronicle article on separation of more than 700 more children from families since June 2018

- HHS Office of Inspector General Report on the Tornillo Influx Care Facility

- Obama administration press release on its response to Central American migration

- Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations report on ORR’s role in preventing trafficking

- Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations oversight report

- Annual ORR Reports to Congress

National Policy Beat in Brief

Handing the Administration a Defeat, the Supreme Court Sends Census Case Back to Lower Court, Leaving the Citizenship Question Off for Now. In a highly anticipated decision issued on the final day of this year’s term, the Supreme Court ruled that a federal judge in New York had properly remanded the case back to the Commerce Department.

In a complicated decision, issued with multiple opinions and dissents, Chief Justice John Roberts, joined by the court’s liberal justices, held that the decision to add the citizenship question was not supported by a reasoned explanation by the Commerce Department, the agency that administers the census. It found that the Commerce Department’s explanation for adding the question—to better enforce the Voting Rights Act—was “incongruent with what the record reveals about the agency’s priorities and decision-making process.”

Civil-rights groups and others challenging addition of the citizenship question charge the Commerce Department’s decision, made by Secretary Wilbur Ross, was driven by political motives, and that adding the question would depress census participation by minorities, advantaging the Republican Party in political redistricting for a decade to come. The discovery late in the litigation of information suggesting a deceased Republican strategist had played a crucial role in the Trump administration’s decision to add the citizenship question has added further intrigue to a case already filled with questions about the motives behind adding the question. (See Box 1 in this earlier Policy Beat for a chronology of events leading to the question’s proposed inclusion.)

Because federal law requires agencies to offer “genuine justifications for important decisions,” the Supreme Court ruled that the district court was right to remand the case, effectively giving the Commerce Department the opportunity to provide an adequate answer. In addition, the high court found that the decision to add the question did not violate the Constitution nor the Census Act.

The result leaves the Trump administration with logistical challenges beyond the legal ones. While the Commerce Department insisted printing the census form needed to begin in July, the Justice Department has said the printing could wait as late as October 31. But there are serious doubts whether all the legal issues surrounding the citizenship question will be resolved before then.

In addition to the fallout from the Supreme Court ruling, the census question separately is under review in a federal district court in Maryland, which decided to revisit the case after newly discovered evidence gave credence to claims that the Commerce Department to add the citizenship question was driven by discriminatory motives. Given the developments in both the New York and Maryland cases, the question will likely work its way back for final resolution by the Supreme Court. Whether there is sufficient time for that to happen before October is now the critical question.

The case has captured widespread attention, largely because the outcome has serious implications on a number of fronts. The count from the 2020 census will determine how many seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and votes in the Electoral College each state receives, as well as the distribution of about $900 billion in federal funds each year for schools, roads, health care, and more. According to Census Bureau experts, the addition of the citizenship question would likely reduce responses among households with at least one noncitizen by at least 8 percentage points, equating to an estimated 9 million people not participating in the count.

- Supreme Court opinion in Department of Commerce et al. v. New York et al.

- NPR article on the ruling

United States-Mexico Agreement Averts Tariffs, Promises Future Asylum Agreement. On June 7, the United States and Mexico reached an agreement aimed at reducing flows of unauthorized immigrants to the U.S.-Mexico border, averting the implementation of President Trump’s announced tariffs on goods imported from Mexico. The president had threatened to impose rising tariffs of up to 25 percent on such goods until illegal immigration ceased. Under the negotiated agreement, Mexico has deployed 6,000 members of its newly formed National Guard to its southern border, with a focus on dismantling human-smuggling organizations. And the United States has expanded implementation of the Migrant Protection Protocols, under which some arriving asylum seekers at the U.S. southern border are sent back to Mexico for the pendency of their U.S. asylum proceedings. The deal was widely criticized as duplicative of terms already agreed to by the two governments.

It was later revealed that an additional agreement was signed, committing Mexican officials to do everything they can to convince the Mexican legislature to agree to a safe third-country agreement, should the United States deem that migration has not decreased enough. Under such an agreement, non-Mexican nationals would be obligated to apply for asylum in Mexico instead of in the United States. The agreement would include a regional component, including a deal currently being negotiated with Guatemala that would obligate asylum seekers from El Salvador and Honduras to first seek asylum in Guatemala.

- U.S.-Mexico Joint Declaration

- Supplementary Agreement between the United States and Mexico

- Reuters article on the asylum negotiations with Guatemala

- Vox article on the U.S.-Mexico agreement

United States, Guatemala Sign Agreement on Migrant Smuggling. Acting Homeland Security Secretary Kevin McAleenan signed a Memorandum of Cooperation (MOC) between the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Guatemalan Ministry of Government aimed at stemming the flow of irregular migration. As part of the agreement, intended to disrupt and interdict human-smuggling operations, dozens of DHS agents and investigators will deploy to Guatemala to advise police and migration authorities. According to Guatemalan officials, at least nine people accused of human smuggling have already been arrested as part of the joint operations.

- DHS press release on the agreement

- Washington Post article on the deployment

Federal Judge Partially Blocks Border Wall Funding. A federal district judge in Oakland, California enjoined the $1 billion transfer of Pentagon counterdrug funding to cover expansions and barrier enhancements on the U.S.-Mexico border. Finding that the transfer exceeded the administration’s authority under federal law, the order limits use of the funds for planned construction in the El Paso sector in Texas and the Yuma sector in Arizona. It does not prevent the administration from tapping other funding sources for those projects.

On June 3, the administration requested that the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals issue an emergency stay against the lower court’s injunction, thus allowing the government to move forward with the construction. That motion is still pending.

In a related case, on June 17, a federal district judge in Washington, DC, at the request of the U.S. House of Representatives, dismissed a lawsuit that the House had brought over the border wall funding. Lawyers for the House had requested the judge dismiss the lawsuit entirely as they appeal to the DC Court of Appeals.

- Preliminary injunction order in Sierra Club et al. v. Donald J. Trump et al.

- Administration emergency motion for a stay in Sierra Club et al. v. Donald J. Trump et al.

- Politico article on the injunction

- The Hill article on the House lawsuit

House Passes Bill to Protect DREAMers, TPS Recipients. On June 4, the House passed a bill that would provide permanent legal status and a path to citizenship to hundreds of thousands of DREAMers—unauthorized immigrants brought to the United States as children. The bill also would offer legal status to Temporary Protected Status (TPS) recipients and a group of Liberians who have benefitted from the Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) program. The Migration Policy Institute estimates up to 2.7 million foreign nationals could receive status under the legislation.

The House vote fell largely on partisan lines, with only seven Republicans joining Democrats to vote for the bill. The legislation is unlikely to be brought for a vote in the Republican-controlled Senate.

Congress has been under increasing pressure to protect DREAMers after President Trump cancelled the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which provides protections and work authorization to some of them. Under several court injunctions, the program has been allowed to continue pending the outcome of the litigation. The administration has appealed these injunctions to the Supreme Court, which has yet to rule on the matter.

- Text of H.R. 6, American Dream and Promise Act of 2019

- Wall Street Journal article on the legislation

- MPI commentary on the American Dream and Promise Act

State and Local Policy Beat in Brief

New York Makes Unauthorized Residents Eligible for Driver’s Licenses. This month New York legislators approved legislation, which Governor Andrew Cuomo quickly signed into law, allowing the state’s unauthorized residents to apply for driver’s licenses. After much debate and hesitation among moderate Democrats, the bill passed in the Senate with just one more vote than the minimum needed, 33 to 29. The law also protects the data of applicants from unwarranted release. Twelve states and Washington, DC currently allow unauthorized immigrants to obtain driver’s licenses.

- Text of NY State Senate Bill S1747B, the Driver’s License Access and Privacy Act

- New York Times article about the bill passage

Federal Judge Blocks Immigration Arrests at Massachusetts Courts. On June 20, in a lawsuit over the ability of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to make arrests at Massachusetts courthouses, a federal judge temporarily blocked the practice. The preliminary injunction stops ICE agents from arresting parties, witnesses, and others visiting courthouses at least for the duration of the lawsuit.

The case was filed in April by two Massachusetts district attorneys, joined by public defenders and immigration advocates. The district attorneys argued that ICE’s arrests in state courthouses hinder their ability to prosecute cases.

- Boston Globe article on the injunction

California Expands Health Care Program to Unauthorized Immigrants. This month California became the first state to offer public health insurance coverage to young adult unauthorized immigrants. On June 14, California lawmakers approved a $214.8 billion budget that included the health-care expansion. Governor Gavin Newsom is expected to sign the spending plan, which will extend California’s Medicaid program (Medi-Cal) to low-income unauthorized immigrants between the ages of 19 and 25. Children under ages 19 and DACA recipients are already eligible for the program. According to state officials, the expansion will affect an estimated 90,000 people. The expansion will take effect on January 1, 2020. Advocacy groups criticized the exclusion of older unauthorized immigrant adults from the budget proposal.

- Sacramento Bee article on the health-care agreement in the budget deal

Connecticut Lawmakers Expand Sanctuary Policies. On June 18, Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont signed legislation to amend and expand the state’s 2013 sanctuary law, the Trust Act. The original law gave law enforcement officers discretion to adhere to ICE detainer requests and set strict requirements for complying with the detainer without a warrant. The newly passed bill will prevent law enforcement from detaining someone on a civil immigration detainer unless it is accompanied by a warrant signed by a judge, or the foreign national is guilty of a serious felony or is on a terrorist watch list. Additionally, the new law limits information sharing with ICE and requires law enforcement officials to inform individuals that ICE has requested their detention.

- Associated Press article on Trust Act amendment