You are here

In Relatively Peaceful Tanzania, Climate Change and Migration Can Spur Conflict

A farmer in Tanzania tends to their crops. (Photo: B. Bannon/UNHCR)

By undermining food security, water availability, and livelihoods around the world, climate change presents a number of risks to peace and security. One such way a changing climate contributes to insecurity is by prompting migration and displacement, which can create tensions and violence between host communities and new arrivals. When climate change and environmental degradation more broadly affect the ecosystems on which communities rely, particularly in agriculture-dependent economies, populations may relocate to satisfy basic needs and seek better services. Repeated shocks and gradual land degradation undercut families’ ability to “build back better,” as developmental organizations often encourage, prompting them to instead seek new livelihoods elsewhere.

Broadly speaking, these movements can exacerbate tensions between social groups. Migration in the midst of climatic changes can add pressure to pre-existing fault lines between communities, create new competition over natural resources, and reinforce scapegoating narratives. Localized flare-ups over land or migration-related demographic shifts can escalate, contribute to civil unrest, and undermine state authority. People’s sense of relative deprivation, particularly in societies that are already riven by factions, can increase the risk of tension and violence between groups. Moreover, rural migrants in many developing countries are often underequipped for changing labor markets, especially in urban areas. This is why climate change is often referred to as a conflict risk multiplier.

Special Issue: Climate Change and Migration

This article is part of a special series about climate change and migration.

While policymakers should not interpret every single violent event as portending the future in a warming world, these incidents can offer lessons about building resilience among climate-affected communities, preparing destination areas for migrants’ arrival, and averting strategies that are counterproductive.

Although many studies have focused on the climate-conflict nexus in fragile contexts such as those in the Horn of Africa and the Sahel, less is known about conflict potentials in relatively peaceful countries such as the United Republic of Tanzania. Tanzania is an interesting case study precisely because Tanzanians have forged a national identity and decades of stability in a country with high ethnic and religious diversity. Yet recent literature warns that the impacts of worst-case-scenario climate change could potentially upend this peace, by leaving little room for communities to adapt in place and few favorable environments left to which individuals and families can migrate internally. Moreover, forthcoming research from the authors confirms the role of climate change in intergroup disputes in Tanzania, adding evidence for communities and the government to reduce risks of tensions through land-management practices, early-warning systems, and inclusive development more generally. This article draws on research conducted in Tanzania in 2019 to evaluate how climate change impacts and migration are exacerbating and causing conflict among rural pastoralists and farmers.

The Picture in Tanzania

There is strong evidence that climate-migration links exist in Tanzania. Average annual surface temperature has increased 1°C since 1960. Warming sea surface temperatures in the Indian Ocean contribute to La Niña–like conditions, leading to flooding, outbreaks of cholera, and destruction of crops and infrastructure. Parts of the country have also suffered from frequent and severe drought in recent years, contributing to extreme reduction in water levels at Lake Victoria, Lake Tanganyika, and Lake Jipe; flood risk; and accelerated disappearance of the glacier on Mount Kilimanjaro, which is just 20 percent of its 1912 size. Future projections suggest that temperatures will be higher nationwide over coming decades, and rainfall levels will vary by location. Rising sea levels could affect an average of 800,000 Tanzanians per year between 2070 and 2100, according to the United Nations Office for Project Services.

Climate impacts such as these act on existing migration drivers, especially economic drivers such as declining agriculture-based household income. Communities whose livelihoods depend on rain-fed agriculture and pasture are most immediately impacted.

This is particularly relevant in Tanzania, where approximately two-thirds of workers are in the agricultural sector, including livestock and fisheries. Some analyses at the national level have found that the combined impact of changing temperature and precipitation, by affecting agricultural subsistence and incomes, increases the probability of rural households engaging in internal migration by 13 percent on average for every 1 percent reduction in agricultural income. Still, research findings are mixed. Some studies evaluating developments at the subnational level found no significant effect from changing rainfall, whereas temperature shocks decrease the probability of migration on average. Others found complex interactions between rainfall variability and out-migration. Multiple studies have shown that overall migration rates in Tanzania remain lower than expected, and smaller than other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Although more research can add depth and nuance to these findings, it is relatively well established that rural dwellers who relocate are more likely to move to areas with more favorable weather conditions and available land for cultivation and keeping livestock.

Importantly, however, not all families will migrate in response to weather shocks and declining conditions. Households with medium levels of wealth may respond to such conditions by migrating, but wealthier and poorer households are less likely to do so. In other words, middle-wealth households appear to leverage previous earnings to invest in migrating to seek higher-return work. Relatively wealthier households are more able to employ alternative livelihood strategies in the face of shocks and tend to remain in place to weather the figurative storm. Meanwhile, the poorest households often cannot afford the costs of migrating—a phenomenon common across the migration spectrum, not just for those facing climate shocks. A large proportion of Tanzania’s population is clustered around the poverty line—about one in eight non-poor Tanzanians fell into poverty between 2010 and 2015, while one in six graduated out—and even minor changes to basic consumption precipitated by environmental or economic shocks can push households into poverty. Scholars warn that some people may easily exhaust their available coping mechanisms and become involuntarily immobile or “trapped” in deteriorating conditions.

These challenges are only likely to get worse. High-end climate change scenarios such as the RCP8.5 projection used as a top-level estimate of future greenhouse gas concentration by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) project severe impacts across Tanzania in the second half of the century. High levels of warming, very hot days, and more erratic, short rainy seasons are likely in Tanzania’s Northern, Central, and Coastal administrative zones. Even the consistent implementation of current pledges in countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement may result in global mean temperatures rising between 2.9°C and 3.4°C above preindustrial levels by 2100. In a business-as-usual scenario, the globe will warm by 4°C or more by 2100, a development that would inflict severe climate impacts on Tanzania. El Niño and Indian Ocean Dipole phases continue to create drought conditions and heavy rainfall, with negative consequences for agricultural productivity and human settlements. These impacts may lead to more forced immobility as well as to more frequent mobility. Without significant advances in sustainable land management, anthropogenic environmental degradation may make some areas practically uninhabitable. While most poor, rural Tanzanians will likely face immobility in the near future, under high-end climate change scenarios migration may eventually become their only recourse for survival.

Aggravating Drivers of Violence

Under certain conditions, climate impacts and migration may aggravate drivers of violence. Research on climate and insecurity globally evaluates conflicts on multiple levels, from small-scale interpersonal violence up through political instability, interstate war, and civilizational collapse. Due to the complexity and multicausal nature of migration decisions, many researchers hesitate to directly link climate change, migration, and conflict. Still, mounting evidence suggests that there is some connection between the phenomena.

Studies have identified a climate signal in, for example, rural-urban migration in Syria that contributed to the onset of civil war there in 2011, recent rural-urban migration leading to intrafamilial conflict in Bangladesh, ethnic conflicts between farmers and mobile pastoralists in Nigeria, and violent conflict between migrants and non-migrants in Pakistan. These studies underscore that climate impacts interact with a larger web of existing sociopolitical and economic grievances that affect means and motivations for violence, further heightened by the exclusion and marginalization often faced by people on the move.

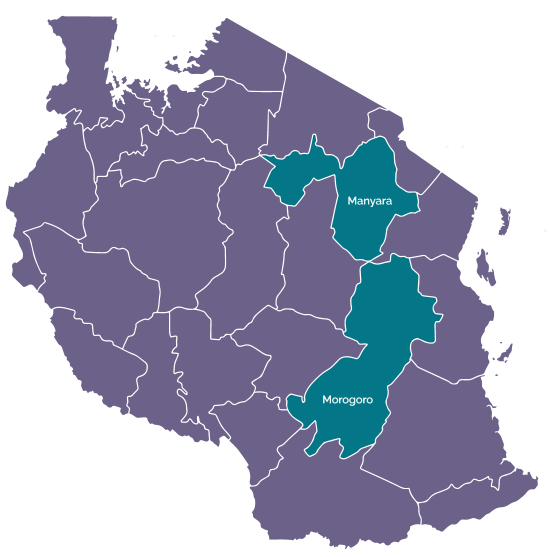

Disputes between farmers and pastoralists (livestock herders) are a frequently cited example, and Tanzania has seen its share of these tensions. Mobile pastoralists—especially those who regularly cross borders, including some Maasai communities along Tanzania’s border with Kenya—are historically among the most politically excluded groups across sub-Saharan Africa. The cross-border identities and economic activities of these groups contribute to their marginalization, including in services provision, land tenure, and political representation. While pastoralists are not the only mobile and migrating group in Tanzania affected by climate change, their movements into primarily sedentary farming communities are similar to other deeply studied interactions and therefore deserve special attention. Furthermore, many pastoralist communities are not represented in national politics and face increasing restrictions at the local level regarding mobility, resource access, land rights, and access to public services. As a result, they are often disproportionately affected by conflicts related to environmental pressures. For example, particularly severe episodes of violent conflicts were reported between pastoralist and farming communities in Kilosa district, Morogoro region in 2000 and 2009; between pastoralists and Tanzania National Parks Agency (TANAPA) in Loliondo, in the northern Arusha region, in 2009; and between pastoralists and authorities at Ihefu valley in Mbarali district, in the Southern Highlands, in 2006.

In response, national and local governments have promoted initiatives to prevent conflict and develop consensus over land use. Among these are strategies to promote selling off livestock, facilitating land-use plans at the village level with both pastoralist and smallholder farming communities, and nullifying title deeds of underdeveloped farms to transfer ownership and use to pastoralists and small-scale farmers.

How Climate Impacts Exacerbate Conflict Risks in Tanzania

Research from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) helps explain the linkages between climate change, human mobility, and conflict in Tanzania, as well as how governments can diffuse tensions. Conflicts are complex and context-specific and should be treated as such. Nevertheless, this article focuses on three main climate-mobility-conflict pathways uncovered through research on the relationships between farmers and mobile pastoralists in rural Tanzania.

Figure 1. Map of Tanzania

First, climate change impacts and environmental changes more generally exacerbate underlying drivers of fragility by directly exacerbating scarcity of resources and weakening livestock. In Tanzania, unpredictable weather compels pastoralists to change their seasonal pattern of movement to seek land and pasture for their livestock. Rainfall patterns are more erratic, making it more difficult for pastoralists to plan regular grazing routes. The result is communities encounter each other in unprecedented locations and more frequently than before. Pastoralist groups can be odds with each other as well as with farmers. Water points for livestock are often the venue for violent disputes.

“Because of climate change, misunderstandings happen, especially because of scarcity of water,” one pastoralist man in the dryland northern Manyara region area explained to the authors. “There are some private water sources and because of droughts, some community members intentionally take their livestock into the water sources and hence conflicts arise.”

Moreover, when livestock movements coincide with changing crop harvests, opportunities for cooperation between pastoralist groups and farmers are threatened. This is more common as herds move more frequently and into new areas, and when farmers migrate to new locations and use different techniques. For example, one male pastoralist elder in the Morogoro region described how new migrant farmers’ habits affected his livelihood. In the past, he would bring his livestock to graze after farmers harvested their crops. “We only graze the residue and not the crops for harvest, so there is no misunderstanding,” he said. But new farmers have arrived using different methods and cultivating year-round “without taking any precautions,” cutting off grazing opportunities.

Second, climate change contributes to the erosion of social relations and institutions within communities, weakening the customary systems of herd management and the usual systems used to resolve conflicts. At the most basic level, pressure on subsistence agriculture puts pressure on families. “There are a lot of conflicts in families now because of lack of enough food. Some men become aggressive when they have no money,” said a female interviewee in the Kiteto district of Manyara region.

Declining agricultural incomes also contribute to working-age men’s decisions to migrate, altering the community’s social structure and customary relationships. In this sense, climate change-induced migration is part of the country’s larger socioeconomic transformation and the social context is paramount in many communities. It is particularly notable that within communities with high social pressures not to migrate, migrating for work becomes more palatable following devastating drought and other hazards.

While migrating to other rural areas is the norm among pastoralists and small-scale farmers in Tanzania, recent research suggests people gravitate towards cities as food and land become more scarce. Yet when they arrive, rural migrants often find barriers to effectively participate in the urban labor market. For example, a number of Maasai pastoralists travel regularly to Dar es Salaam for short-term work as security guards, hairdressers, or sellers of small goods. One Maasai man in his late 20s in the city told the authors that he moved to Dar es Salaam from a dryland area near Simanjiro because of drought, among other reasons.

“There is not enough food for the families. Livestock are weak and we can’t sell them for a good price, and hence we made the decision to come to town looking for jobs,” he said, referring to himself and his older male travel partner. “Many of those who stayed at home tend to have enough cows to take care of their families compared to those who moved away… We have our younger brothers at home, and they are the one helping to take care of the livestock.” Herds are often left with younger male family members, around ages 9 to 25. These men and boys often lack the maturity and civility to resolve conflicts or to reinforce customary and spontaneous agreements with farmers, contributing to conflicts.

Third, climate change can disrupt power relations and strain fault lines between different communities. Climate impacts make resources more scarce, pushing farmers and pastoralists to reach new land-use agreements in which the latter often have a relatively weak negotiating position. In addition to their relative political exclusion noted above, pastoralists tend to be disadvantaged by transient formal tenure or use rights.

Customary reciprocal relationships create opportunities for cooperation and can help divided communities overcome these challenges. For example, some farmers rely on pastoralists to clear their fields of crop residue, making it easier to plow and plant. Diplomacy, honoring historical arrangements, and mediation of disputes are paramount. The male Maasai elder in Morogoro region explained:

As pastoralists, we ask for permission to graze our cows in certain areas. You must talk to the villagers who will give you permission to enter their village general land, but you must pay a little amount of money… There are conflicts here, but the source is the government because the [customary] land boundaries are not respected, and pastoralist land is taken. We need land-use plans, especially boundaries which are respected by everyone.”

Mitigation, Land-Use Plans, and Tanzania’s Future

The linkages between climate change, human mobility, and conflict are complex. Migration by itself does not create conflict, but tensions may easily arise when rapid and unmanaged movements of people combine with policies that exclude and marginalize them or fail to support host communities.

National and local governments in Tanzania are promoting multiple initiatives around the country to prevent conflicts and develop consensus over land-use plans, to varying degrees of success. Villages are supported by the national government and development partners to inclusively develop land-use plans and adopt bylaws to manage and protect land for cultivation, grazing areas, water points, livestock routes, and other resources. Certificates of customary rights of occupancy are issued to individuals and community groups including pastoralists and farmers. Such plans and bylaws help to govern internal migration and clarify land-use boundaries, hence reducing conflicts between migrants and host communities. Other initiatives bring multiple villages together to develop joint land-use plans. Shared plans can reduce boundary conflicts, promote rangelands improvement, and address water and pasture scarcity that influence pastoralist mobility.

For example, between 2010 and 2020 the Sustainable Rangelands Management Project (SRMP) assisted clusters of villages in Kiteto district, Manyara region to secure village lands including shared grazing lands. The project intended to address root causes of conflict by holding several trainings on conflict resolution and transformation at local, district, national, and regional levels of government. Importantly, since many disputes are ultimately resolved at the district level, the multi-stakeholder platform pioneered in Kiteto district has been replicated in other villages with similar characteristics in Chalinze, Mvomero, Kilosa, and Iringa Rural districts. It could be further expanded more broadly across the country. The focus on land-use planning for sustainable development has allowed for local flexibility, which in turn allows for the integration of customary arrangements. However, this approach remains vulnerable to local power dynamics, slack implementation, and misuse.

The Tanzanian government is working to address root causes of unplanned forced mobility and conflict, especially natural resource scarcity and boundary conflicts. In addition to encouraging the development of land-use plans, the government has developed a climate change strategy, provided technical and agricultural inputs, and worked to improve water infrastructure. Unfortunately, severe climate change impacts could upend this progress and reverse development gains generally. As climate change erodes rural livelihoods, it becomes more difficult for communities to build back better. Rural herders and farmers are rarely equipped to thrive in urban labor markets, limiting the ability of cities to offset the economic toll of climate impacts. Moreover, prolonged hardship is more likely to lead to conflict as dispute mechanisms break down over time, suggesting that protracted stressors pose greater dangers the longer they persist.

To best prepare for a warmer future, Tanzania and its development partners in governments, intergovernmental agencies, and elsewhere can work to mitigate and avoid climate change, support community development and resilience-building, and establish large-scale adaptation measures such as reforestation and afforestation. Importantly, small improvements to gather data on weather, climate, internal migration, and displacement can help build an evidence base to better inform communities, policymakers, and development organizations. Weather and climate data are often limited, depriving farmers and pastoralists of crucial forecasts. Moreover, more knowledge is needed to find what works and what does not in confronting climate change, maximizing the positives of migration and pastoralist mobility, preventing conflict, and resolving land disputes. There is no silver bullet to avoid all harm, but an unmanageable catastrophe is not inevitable.

Sources

Ayeb-Karlsson, Sonja, Christopher D. Smith, and Dominic Kniveton. 2018. A Discursive Review of the Textual Use of "Trapped" in Environmental Migration Studies: The Conceptual Birth and Troubled Teenage Years of Trapped Populations. Ambio 47 (5): 557–73. Available online.

Benjaminsen, Tor A., Faustin P. Maganga, and Jumanne Moshi Abdallah. 2009. The Kilosa Killings: Political Ecology of a Farmer–Herder Conflict in Tanzania. Development and Change 40 (3): 423–45.

Bhattacharyya, Arpita and Michael Werz. 2012. Climate Change, Migration, and Conflict in South Asia: Rising Tensions and Policy Options across the Subcontinent. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. Available online.

Blocher, Julia M. et al. Forthcoming. Assessing the Evidence: Climate Change and Migration in the United Republic of Tanzania. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Cattaneo, Cristina et al. 2019. Human Migration in the Era of Climate Change. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 13 (2): 189-206. Available online.

De Jode, Helen and Fiona Flintan. 2020. How to Prevent Land Use Conflicts in Pastoral Areas. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development. Available online.

Detges, Adrien et al. 2020. 10 Insights on Climate Impacts and Peace: A Summary of What We Know. Berlin: adelphi research gemeinnützige GmbH and Potsdam: Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Available online.

Folami, Olakunle Michael and Adejoke Olubimpe Folami. 2013. Climate Change and Inter-Ethnic Conflict in Nigeria. Peace Review 25 (1): 104-10.

Foresight. 2011. Migration and Global Environmental Change. London: The Government Office for Science. Available online.

Gleick, Peter H. 2014. Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria. Weather, Climate, and Society 6 (3): 331–40. Available online.

Hsiang, Solomon M., Marshall Burke, and Edward Miguel. 2013. Quantifying the Influence of Climate on Human Conflict. Science 341 (6151).

International Crisis Group. 2017. Herders Against Farmers: Nigeria’s Expanding Deadly Conflict. Brussels: International Crisis Group. Available online.

Kalenzi, Deus. 2016. Improving the Implementation of Land Policy and Legislation in Pastoral Areas of Tanzania: Experiences of Joint Village Land Use Agreements and Planning. Rome: International Land Coalition. Available online.

Kelley, Colin P., Shahrzad Mohtadi, Mark A. Cane, Richard Seager, and Yochanan Kushnir. 2015. Climate Change in the Fertile Crescent and Implications of the Recent Syrian Drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (11): 3241-46. Available online.

Mallick, Bishawjit and Joachim Vogt. 2012. Cyclone, Coastal Society and Migration: Empirical Evidence from Bangladesh. International Development Planning Review 34 (3): 217–40.

Raleigh, Clionadh. 2010. Political Marginalization, Climate Change, and Conflict in African Sahel States. International Studies Review 12 (1): 69–86. Available online.

Rigaud, Kanta Kumari et al. 2018. Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online.

Uexkull, Nina von, Mihai Croicu, Hanne Fjelde, and Halvard Buhaug. 2016. Civil Conflict Sensitivity to Growing-Season Drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113 (44): 12391–96. Available online.

Vivekananda, Janani, Martin Wall, Chitra Nagarajan, Florence Sylvestre, and Oli Brown. 2019. Shoring Up Stability: Addressing Climate and Fragility Risks in the Lake Chad Region. Berlin: adelphi research gemeinnützige GmbH. Available online.