You are here

Texas Once Again Tests the Boundaries of State Authority in Immigration Enforcement

Texas Governor Greg Abbott speaks at a political event in Arizona. (Photo: Gage Skidmore)

Citing the high volume of illegal border crossings, Texas Governor Greg Abbott has declared a state of disaster for relevant state agencies and border counties and embarked on a slew of actions to fill in areas that he believes the Biden administration has neglected on immigration enforcement. Most important among these are directives to build additional barriers on the U.S.-Mexico border, ramp up arrests of unauthorized immigrants by state and local police, and revoke the licenses of shelters in Texas that house unaccompanied child migrants for the federal government.

The timing and political backdrop for these measures will be underscored when the governor visits the border on June 30 alongside former President Donald Trump. For Trump, immigration was a signature issue, both as a campaigner and then as president, and with this visit he is making clear it will continue to be one as he seeks to retain his control over the Republican Party. Immigration remains a politically potent issue nationally, particularly since record numbers of migrants and asylum seekers have been intercepted at the border in recent months. Vice President Kamala Harris, President Joe Biden’s designated emissary to address rising migration from Central America, visited the border just days before Trump, following criticism particularly from Republicans who have claimed the administration’s policies have brought on the rising number of arrivals.

The federal government and border states have repeatedly sparred over authority for immigration enforcement, particularly while Democrats have inhabited the White House. From 2014 to 2016, Texas led the opposition to the Obama administration’s attempt to expand legal protections for DREAMers brought to the United States as children and the parents of U.S. citizens and permanent residents, taking the challenge all the way to the Supreme Court. Texas now seems primed to resume its position as chief foil for the Biden administration on immigration. While the state has allocated more than $4.4 billion for episodic border enforcement since 2008, its policies may be less likely to materially alter the situation on the ground than to advance a political agenda and embody a political spirit of opposition.

Texas Takes Matters into Its Own Hands

Texas law broadly defines a disaster as “the occurrence or imminent threat of widespread or severe damage, injury, or loss of life or property resulting from any natural or man-made cause.” It is exclusively up to the governor to declare whether a disaster has occurred.

While Abbott, a Republican, based his declaration on his assessment of the current situation at the border, with activity at a 20-year high, Texas has experienced periods of sharply increased illegal crossings in the past, most recently in spring 2019 during the Trump administration, when no state emergency designation occurred. There are some differences between the current situation and that of 2019. From October 2020 through May 2021, the U.S. Border Patrol encountered migrants and asylum seekers in Texas border sectors nearly 606,000 times, which was 180,000 more than during the same period in fiscal year (FY) 2019, during the previous spike. However, 70 percent of migrants encountered at the Texas border in FY 2021 were blocked from entering U.S. territory and immediately expelled to Mexico or their country of origin under a pandemic-prompted restriction that was not in place in FY 2019. There is thus a question of whether the pressures at the border changed significantly this year compared to 2019. What had certainly changed, however, was Biden entering office. So the timing of the declaration and other immigration measures raised some eyebrows.

Being a thorn in the side of the federal government is not new for Texas. It had previously launched a successful legal challenge halting the Obama administration’s attempt to expand the population eligible for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. As a result of litigation by Texas and others, the Obama administration also was blocked from extending protection from deportation to parents of U.S. citizens and permanent residents under a program known as Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA). A subsequent lawsuit challenging the legality of the original DACA program created in 2012 remains pending in federal district court in Texas. And in the first weeks of the Biden administration, Texas successfully sued to block Biden’s 100-day moratorium on deportations.

Litigation has been the principal avenue for Texas’s assertive leadership on immigration. Indeed, state Attorney General Ken Paxton built a reputation as a potent legal force to take on Democratic administrations. But with many of Biden’s actions perceived as crafted in ways that make them more impervious to legal challenge than measures from both Barack Obama and Trump—coupled with recent political vulnerabilities for Paxton, who faces felony securities fraud charges and allegations of abuse of office—Abbott may have shifted toward a political strategy to challenge the Biden administration.

Although the power to regulate immigration historically has been seen as an exclusively federal authority, Congress and the courts over the years have allowed states some role in immigration enforcement policy. As immigration has increasingly become a polarized issue, state and local assertion of authority has taken sharper political overtones, with both Democrats and Republicans eager to signal their partisan bona fides through policies ranging from reducing or mandating cooperation with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to sending National Guard members to the border.

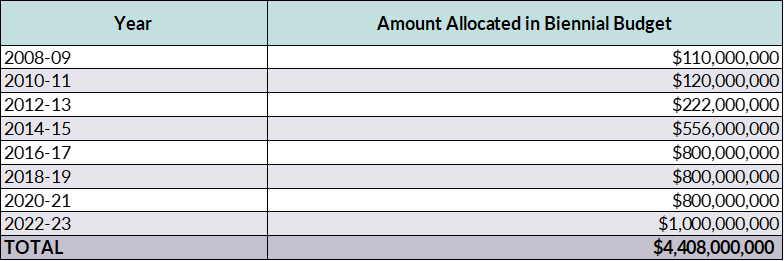

Since 2005, Texas lawmakers have appropriated billions of dollars for border security, allocating at least $800 million in every biennial budget since Abbott took office in 2015. The 2022-23 budget bumped that to $1 billion, using general funds partly available because of federal COVID-19 relief money for other budget items. This has given the state funding to back up its efforts to enact its own immigration policies (see Table 1).

Table 1. Texas State Border Security Appropriations, 2008-23

Sources: Amounts for 2008-15 from Dylan Baddour, “Explained: How Texas Built a Border Army,” Houston Chronicle, August 30 2016, available online; amount for 2016-17 from Texas Legislative Budget Board, “State Funding for Border Security” (Presentation to the House Appropriations Committee, Austin, Texas, February 2017) available online; amount for 2018-19 from Texas Legislative Budget Board, “State Funding for Border Security” (Presentation to the House Appropriations Committee, Austin, Texas, January 2019) available online; amount for 2020-21 from Cassandra Pollock, “Texas Will Deploy 1,000 National Guard Troops to the Border Amid Migrant Surge,” Texas Tribune, June 21, 2019, available online; amount for 2022-23 from Nate Chute, “What We Know About Gov. Greg Abbott's Plans for a Texas Border Wall,” El Paso Times, June 16, 2021, available online.

Though Texas’s focus on immigration has received consistent support from the state legislature, there is speculation that the governor’s recent announcements are mostly for political consumption, motivated by primary pressure from the right ahead of his 2022 re-election, and with his eye potentially on the presidency in 2024. The Houston Chronicle editorial board called Abbott’s impending wall a “partisan shtick” that is “cynical, short-sighted, and irresistibly simple,” and the San Antonio Express-News editorial board called it a “political prop.” Whatever the motivation, it is apparent that Texas is challenging federal immigration policy on more fronts at one time than ever before.

Building a Border Wall

After Biden terminated border wall construction that started under Trump, Abbott announced that Texas would step in to build border barriers by spending $250 million originally appropriated for state correctional facilities, supplemented by a crowdfunding campaign that raised $459,000 from private donors within its first week. Polling suggests Abbott may find political support for this move. In April, a University of Texas/Texas Tribune poll found that a plurality of Texas voters (37 percent) cited border security and immigration as the biggest problems facing the state. Many Texans—particularly Republicans—may be on board with Abbott’s proposed solution: a recent Quinnipiac poll found that 50 percent of the state’s voters (including 89 percent of Republicans) supported building a border wall, roughly similar to previous poll results in 2019.

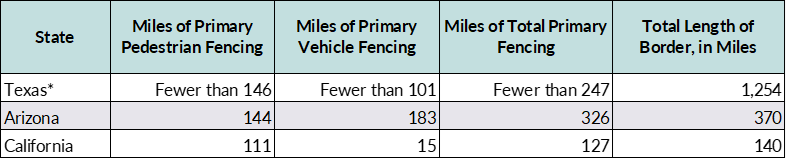

Regardless of political support, the state has authority to build the wall only on state-owned land, of which there is little along the border, or on private property where landowners agree to such construction. Abbott has yet to identify where the state intends to build the wall. Previous federal efforts to build border barriers in Texas have encountered difficulties, because so much land is privately owned. By the end of June 2020, there were fewer than 146 miles of primary fencing built at a height to deter pedestrian crossings and fewer than 101 miles of primary fencing built to keep out vehicles along Texas’s 1,254-mile border with Mexico. (These 247 total miles include about 165 miles of fencing in what the government defines as the El Paso border sector, which encompasses all of New Mexico’s border and part of the Texas border; it is not possible to identify the precise length of fencing in Texas.) In comparison, there were 144 miles of primary pedestrian fencing and 183 miles of primary vehicle fencing built in Arizona, which has an approximately 370-mile-long border with Mexico, and 111 miles of primary pedestrian fencing and 15 miles of primary vehicle fencing in California, covering most of its 140-mile border.

Table 2. Miles of Primary Fencing along the U.S. Southwest Border by State, as of June 2020

Note: Data for Texas include fencing in New Mexico.

Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Southwest Border: Information on Federal Agencies’ Process for Acquiring Private Land for Barriers (Washington, DC: GAO, 2020), available online.

Of the border states, Texas has the most privately owned tracts of border land. In order to build on it, the government would need to acquire land from landowners either through a negotiated sale or by exercising its eminent domain power. The process of taking land through eminent domain is protracted, particularly in Texas; U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has estimated that this process would take 21 to 30 months in south Texas, compared to 12 months in other regions. By July 2020, according to the Government Accountability Office, just 123 privately owned tracts of land in Texas had been acquired by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), out of the 1,069 total wanted for barrier construction. The rest were embroiled in the eminent domain process. (Data were unavailable regarding the status of an additional 21 tracts of land the federal government wanted to acquire.)

The governor’s own statements indicate he may try to build fencing on voluntarily donated land, in an attempt to bypass obstacles acquiring private land. This strategy could work if the sole objective is to construct barriers anywhere along the border. But if barrier placement is meant to be strategic, and if barrier sections are meant to be contiguous, it is unlikely that voluntary donations will yield that result.

Past Challenges of State and Private Border Security Measures

Past attempts by state and private entities to build border barriers or install other security technology have generally failed. The most recent effort, by the private group We Build the Wall, raised $25 million from individual donors by mid-2020 but ended in scandal when its four organizers were indicted for fraud. While this experience may indicate the potential for success in Abbott’s crowdfunding strategy, it is also possible that donors will be more skeptical of such efforts after having been burned.

Arizona has also previously attempted to build its own border wall. Legislation in 2011 set up a fund for donations to go toward building a barrier along the state’s border with Mexico. While the goal had been to raise $50 million, just $270,000 was raised by the time the effort was abandoned in 2017. The money was subsequently given to a border-county sheriff’s department for border security technology.

During the previous decade, Abbott’s predecessor, Rick Perry, tried to create a virtual wall, promising during his 2006 gubernatorial campaign to install $5 million worth of security cameras along the border. Using $4 million in federal funds, because state lawmakers refused to provide funding, he put in place a program allowing the public to view live video from the border and report perceived illegal activity to sheriffs’ departments. A total of 29 cameras were installed, which led to 26 arrests by 2010—a cost of about $153,800 per arrest, according to a Texas Tribune calculation.

Increasing Arrests and Detention

In his May 31 order declaring a state of disaster, Abbott directed state law enforcement “to prevent the criminal activity along the border, including criminal trespassing, smuggling, and human trafficking, and to assist Texas counties in their efforts to address those criminal activities.” In line with the directive, the state has deployed 1,000 Department of Public Safety troopers and 500 National Guard members.

Arizona has also sent state troopers and National Guard forces to the border. In addition, Abbott and Arizona Governor Doug Ducey, a fellow Republican, announced in June that they would activate a state mutual-aid agreement known as the Emergency Management Assistance Compact and request that other states send their own law enforcement officers to assist with arrests along the border. This compact has been used many times to provide support when a state experienced fallout from a natural disaster or hosted an event needing extra security, but it had never before been used for immigration enforcement. By mid-June, Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Iowa, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and South Dakota had sent law enforcement officers to the border, and Georgia and South Carolina had sent National Guard troops, according to Abbott.

Arrests made under the disaster declaration carry an extra punch, since punishments for some state crimes increase when committed in a disaster-designated area. For example, under normal circumstances in Texas there is not necessarily a minimum sentence for criminal trespassing, but during a disaster a minimum of six months’ confinement is imposed. As ordered by the governor, criminal trespassing will likely constitute a major share of arrests, and state laws against trafficking and smuggling can also be enforced. Abbott has also directed increased arrests for federal crimes.

Though the near-exclusive authority of the federal government to enforce immigration laws is well-established, federal law defines a limited role for state and local police. For civil enforcement of federal immigration law, Section 287(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) authorizes state and local governments to participate only under federal supervision. For criminal enforcement, Congress has explicitly authorized state and local police to arrest violators of two criminal immigration provisions: INA Section 274, which prohibits smuggling and trafficking; and Section 276, which establishes criminal penalties for illegal re-entry following removal. But even here, the role of state and local police is circumscribed. First, they cannot stop individuals solely to inquire about their immigration status—there must be another primary reason to detain someone for violating a criminal statute—and the duration of detention cannot exceed what is necessary for criminal law enforcement purposes. And second, state and local authorities can detain someone they suspect of illegally re-entering the United States only until federal immigration agents arrive and take that person into custody.

In calling for other states to send resources to Texas, Abbott cited a 1996 opinion from the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) finding that state and local law enforcement personnel could make arrests for all criminal immigration violations, though not for civil violations such as unlawful presence in the United States. While federal statute overrides OLC opinions, even this opinion made clear that foreign nationals arrested using this authority could be detained only long enough for immigration agents to arrive and decide how to proceed. Thus, any arrest made by state officials for federal criminal violations would meet a legal challenge if it did not adhere to these requirements. The state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union has warned counties against arresting people due to their immigration status, a likely prelude to a court battle.

The possibility of legal challenges has increased as the facilities where arrestees will be held have become public. On June 16, Texas started transferring prisoners out of a state prison in Dilley to make room for migrants facing state or federal charges. This prison has faced recent problems with understaffing, high temperatures, the stress of COVID-19, and easily breakable cell locks, all of which led to a riot in July 2020. Further, prison is a harsher punishment than is typical for most people arrested crossing the border illegally. Most are held in immigration detention, which is not supposed to be punitive, although a smaller share is criminally prosecuted, with some receiving sentences of time served.

Ending State-Licensing of Shelters for Unaccompanied Children

The third prong of Abbott’s policy is to instruct the state agency that licenses shelters for children in Texas to terminate the licenses for those that receive grants from and contract with the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to provide care for unaccompanied child migrants. Existing licenses must be wound down by August 30, affecting up to 52 facilities holding 4,200 minors as of mid-May.

This plan would not stop unaccompanied children from coming to the United States, but only require that they be held elsewhere. Likely, new child migrants would be diverted to temporary emergency facilities, which have offered worse conditions than shelters and are significantly more expensive. Ironically, these facilities could be located in Texas. One emergency facility in Texas, at Fort Bliss, has come under significant scrutiny. Reports have revealed that children held there, some for extended periods, have been suffering from depression and anxiety leading to incidents of self-harm; have struggled to get medical treatment despite outbreaks of lice, COVID-19, flu, and strep throat; and receive little education or recreational time. As of early June, more than 100 children had lived at Fort Bliss for more than two months. The facility housed 790 children as of June 28, but it can hold up to 10,000 children and could see its population rise if licensed shelters in Texas are closed pursuant to the governor’s order.

HHS has threatened to sue the state if it proceeds with terminating licenses, arguing that targeting its grantees constitutes unconstitutional discrimination against agencies that work with the federal government. Under the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause, federal law supersedes that of the states and states may not make their own contradictory laws in areas regulated by the federal government or impede it from carrying out laws enacted by Congress.

More than a Political Gambit?

Though Abbott’s new actions on immigration enforcement have received significant attention, it is less clear whether his plans can be implemented. And it is even less certain whether they can attain their intended goals.

For wall construction, the cooperation of landowners is key, but far from assured. Even if the planned delicensing of federally contracted shelters survives a likely legal challenge, the federal government may simply use or set up other emergency intake sites in Texas. And although the governor may have more exclusive control over the ability to dispatch law enforcement to arrest and detain border crossers, the move will surely invite legal scrutiny that may be hard to overcome.

If the intended goal of Abbott’s strategy is to stop illegal immigration, Texas will almost certainly come up short. Border walls, even when carefully planned, do not stop illegal immigration; they divert it. If Texas increases arrests, many migrants will choose a different part of the border to cross. If children cannot be housed in state-licensed shelters in Texas, they will be held in alternative facilities. Thus, the governor’s strategy may be driven less by a desire to attain real outcomes and more to generate winning soundbites in a hyperpolarized environment.

Sources

Abbott, Greg. 2021. Governor Abbott Amends Border Crisis Disaster Declaration. Proclamation, June 25, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Proclamation by the Governor of the State of Texas. Proclamation, May 31, 2021. Available online.

Abbott, Greg and Douglas A. Ducey. 2021. Letter from the Governors of Texas and Arizona to U.S. Governors. June 10, 2021. Available online.

American Civil Liberties Union of Texas. 2021. Texas Border Counties Put on Notice Not to Participate in Gov. Abbott’s Border Actions. Press release, June 24, 2021. Available online.

Andersson, Hilary. 2021. 'Heartbreaking' Conditions in US Migrant Child Camp. BBC News. June 23, 2021. Available online.

Baddour, Dylan. 2016. Explained: How Texas Built a Border Army. Houston Chronicle, August 30, 2016. Available online.

Barragán, James. 2021. Gov. Greg Abbott Announces Texas Is Providing Initial $250 Million "Down Payment" for Border Wall. Texas Tribune, June 16, 2021. Available online.

Beard Rau, Alia. 2015. Cochise County Sheriff to Get Donations Meant for Border Wall. Arizona Republic, November 9, 2015. Available online.

Blakinger, Keri. 2020. Breaking Out with A Bar of Soap. The Marshall Project, August 11, 2020. Available online.

Chute, Nate. 2021. What We Know About Gov. Greg Abbott's Plans for a Texas Border Wall. El Paso Times, June 16, 2021. Available online.

Emergency Management Assistance Compact. N.d. Select Events and Historical Landmarks. Accessed June 24, 2021. Available online.

Garrett, Robert T. 2021. Texas Ramps Up Border Security Spending, Uses Feds’ Dollars for One-Time Expenses in Spending Bill. Dallas Morning News. May 21, 2021. Available online.

Grissom, Brandi. 2010. $153,800 Per Arrest. Texas Tribune, April 20, 2010. Available online.

Houston Chronicle Editorial Board. 2021. Editorial: Abbott's Texas Border Wall Gimmick Isn't Tough. It's Trite. Houston Chronicle. June 13, 2021. Available online.

Lydgate, Joanna. 2010. Assembly-Line Justice: A Review of Operation Streamline. Policy brief, Chief Justice Earl Warren Institute on Race, Ethnicity, and Diversity, University of California, Berkeley Law School, Berkeley, CA, January 2010. Available online.

Montoya-Galvez, Camilo. 2021. Migrant Children Endure "Despair and Isolation" inside Tent City in the Texas Desert. CBS News. June 22, 2021. Available online.

Oxner, Reese. 2021. Texas Empties Prison to Prepare to Detain Immigrants Arrested During Ramped-up Border Enforcement. Texas Tribune, June 17, 2021. Available online.

Pollock, Cassandra. 2019. Texas Will Deploy 1,000 National Guard Troops to the Border Amid Migrant Surge. Texas Tribune, June 21, 2019. Available online.

Ramsey, Ross. 2019. Texas Voters Deeply Divided on Voting, a Border Wall and Diversity, Says UT/TT Poll. Texas Tribune, March 6, 2019. Available online.

---. 2021. Texas Voters Are as Concerned about Border Security as about the Pandemic, UT/TT Poll Finds. Texas Tribune, May 4, 2021. Available online.

Rodríguez, Cristina, Muzaffar Chishti, and Kimberly Nortman. 2007. Testing the Limits: A Framework for Assessing the Legality of State and Local Immigration Measures. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Rodríguez, Paul. 2021. Letter from Deputy General Counsel, Department of Health and Human Services, to Greg Abbott, Governor of Texas; Jose A. Esparza, Deputy Secretary of State; and Cecile Erwin Young, Executive Commissioner, Health and Human Services Commission; Re: May 31, 2021 Proclamation. June 7, 2021. Available online.

San Antonio Express-News Editorial Board. 2021. Editorial: Abbott’s Wall a Monument to Posturing. San Antonio Express-News. June 18, 2021. Available online.

Sandoval, Edgar. 2021. Texas Says It Will Build the Wall, and Asks Online Donors to Pay for It. New York Times, June 16, 2021. Available online.

Shaw, Adam. 2021. Gov. Abbott Says Texas Border Wall Project Raises $397,000 in First Week. FOX News, June 22, 2021. Available online.

Steinhauser, Paul. 2021. Texans Divided on GOP Gov. Abbott’s Proposed Border Wall, 2022 Reelection: Poll. FOX News. June 23, 2021. Available online.

Texas Code, Section 418.014, “Declaration of State of Disaster.” Available online.

Texas Legislative Budget Board. 2017. State Funding for Border Security. Presentation to the House Appropriations Committee, Austin, Texas, February 2017. Available online.

---. 2019. State Funding for Border Security. Presentation to the House Appropriations Committee, Austin, Texas, January 2019. Available online.

Texas Penal Code, Section 12.50, “Penalty If Offense Committed in Disaster Area or Evacuated Area.” Available online.

Thayer, Rose L. 2021. Texas Governor Sends 500 National Guard Troops to Border for 'Humanitarian Crisis.’ Stars and Stripes, March 9, 2021. Available online.

Trovall, Elizabeth. 2021. Dozens of Texas Migrant Shelters Told to ‘Wind Down’ Operations by End of August After Abbott’s Disaster Declaration. Houston Public Media, June 2, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legal Counsel. 1996. Assistance by State and Local Police in Apprehending Illegal Aliens. February 5, 1996. Available online.

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2020. Southwest Border: Information on Federal Agencies’ Process for Acquiring Private Land for Barriers. Washington, DC: GAO. Available online.