You are here

Controversial U.S. Title 42 Expulsions Policy Is Coming to an End, Bringing New Border Challenges

U.S. Border Patrol agents prepare to transport unauthorized migrants to Mexico under Title 42. (Photo: Jerry Glaser/U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

Editor's note: This article was updated on April 1, 2022 to reflect the U.S. government's decision to end Title 42; it also updated data on the expulsion rates of migrants by nationality starting in April, 2020.

Two years after its implementation, the controversial Title 42 policy that uses COVID-19-related grounds to authorize immediate expulsions of migrants, including would-be asylum seekers, arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border is nearing its end. Instituted by the Trump administration on March 20, 2020, and continued by the Biden administration, the first-ever use of the policy ushered in an anomalous—and, to critics, shameful—period of mass expulsions. Yet its unwinding, which will occur May 23, may result in massive new arrivals at the southwest border, raising questions about how to respond to them.

Through February, 1.7 million expulsions had been carried out under this policy, 1.2 million of them during the Biden administration. During the Trump administration, 83 percent of migrant encounters at the border led to expulsions, compared to 55 percent so far under the Biden administration. The rest have been processed under standard immigration laws, which for many allow at least entry into the United States and the opportunity to seek asylum or other humanitarian protections. Encounter numbers refer to events, not individuals; a single person trying to cross the border can be caught, expelled, and then repeat the attempt multiple times, each of which would count as a new expulsion. In fact, during the Title 42 era, recidivism (the repeat encounter of a previously intercepted migrant) soared.

The director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which holds the authority to deploy Title 42 under the 1944 Public Health Service Act, announced the public-health order would be lifted as of May 23. A pair of March court rulings may have ushered along the program’s demise: In one, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia affirmed that the administration could use Title 42 to expel arriving migrants but could not send them to countries where they would face persecution or torture. In a separate opinion, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas ruled against the Biden administration’s exemption of unaccompanied children from the application of Title 42, prompting the CDC to terminate the order for these minors altogether. Thus, the Biden administration was being pulled in two opposing directions.

Another reason for the end of the public-health order is that U.S. cases of COVID-19 have been trending downward, vaccinations are widely available, and the government is encouraging a return to normal life. Moreover, since November 8 fully vaccinated authorized travelers have been permitted to enter the United States, including at the U.S.-Mexico border, which seems inconsistent with an ostensible public-health policy that expels migrants crossing without authorization regardless of vaccination status. In recent months, cries to end the expulsions policy have grown louder, including from President Joe Biden’s fellow Democrats.

Whenever Title 42 was terminated, the government inevitably was going to face major challenges soon after. Even with the expulsions policy in place, migrant encounters at the border had reached a new record. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is reportedly bracing for a “mass migration event” once the public-health order is lifted, presenting both logistical and operational challenges at the border and a political hazard for Democrats ahead of midterm elections. A new policy to change processing of border asylum cases could help relieve border pressures over the longer term, though not immediately.

This article reviews how Title 42 has affected migration at the U.S.-Mexico border and the likely consequences of its termination.

Border Arrivals under Title 42

Two major patterns have been evident since the expulsions policy was implemented: a re-emergence of unauthorized and, often, repeat crossings by Mexican single adults in addition to Central American families and unaccompanied children who had predominated in recent years, and new record levels of arrivals from countries beyond Mexico and Central America. From about 1970 to 2010, irregular migration at the U.S. southwest border mainly consisted of Mexican single adults crossing in search of work, but in the 2010s, migration from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras increased and began to outpace a declining Mexican flow. The share of single adults, meanwhile, shrank while the share of families grew.

The implementation of Title 42 was likely partially responsible for interrupting this evolution. It incentivized repeat crossings and its application was inconsistent for citizens of countries other than Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—and even among citizens of those countries. But it was not the only factor: Economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic led more people to seek jobs in the United States, lenient Mexican visa policies facilitated movement of citizens of some countries, and these patterns were exacerbated by push factors including insecurity, government corruption, poverty, and environmental challenges in migrants’ countries of origin. Together, these conditions resulted in more migrant encounters in fiscal year (FY) 2021 than in any previous year, with a record 1.66 million encounters between ports of entry at the southwest border.

Repeat Crossings on the Rise

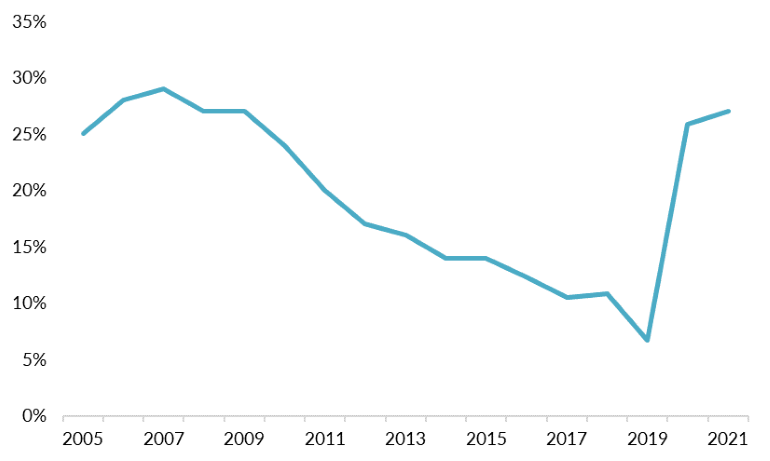

Since expulsions began, recidivism has surged, reaching levels last seen in the 2000s, before U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) stopped simply returning most Mexican migrants back to Mexico and began imposing more serious consequences for unauthorized crossings and escalating penalties for repeat crossers (see Figure 1). Migrants expelled under Title 42 have not been subjected to these formal consequences, including expedited removal and criminal prosecution, but instead have been granted voluntary return to Mexico.

Figure 1. Recidivism Rate among Unauthorized Migrants Encountered by U.S. Border Patrol at the U.S.-Mexico Border, FY 2005-21

Sources: For fiscal years (FY) 2005-13, U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Congressional Budget Justification FY 2015, accessed March 23, 2022, available online; for FY 2014-15, DHS, Congressional Budget Justification FY 2017—Volume I, accessed March 23, 2022, available online; for FY 2016-20, DHS, U.S. Customs and Border Protection Budget Overview: Fiscal Year 2022 Congressional Justification, accessed March 23, 2022, available online; for FY 2021, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “CBP Enforcement Statistics Fiscal Year 2022,” accessed March 23, 2022, available online.

However, the expulsions policy has allowed for exceptions which not been uniformly applied. Families have often been allowed into the United States, and so are all unaccompanied children following a November 2020 court decision. For families and children who have been expelled, Title 42 at first imposed few consequences for repeat crossings, leading to a rise in recidivism for these populations, too. However, in mid-2021 the Biden administration ramped up expulsions of families via flights to southern Mexico, which may have tempered some of the recidivism.

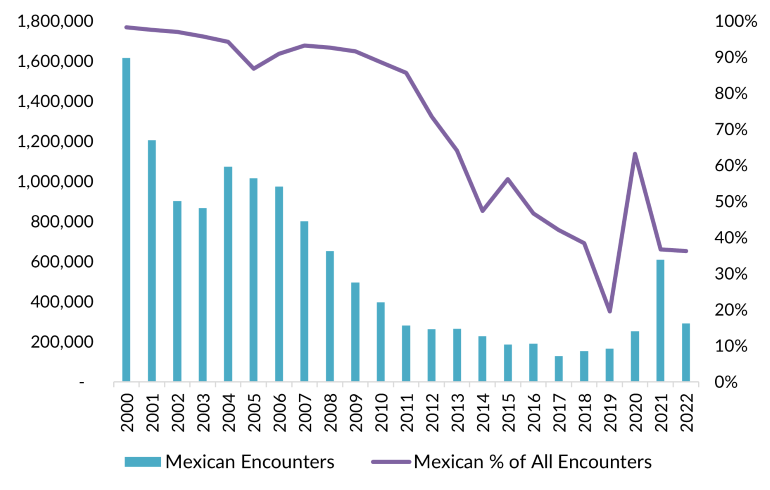

Given that Title 42 has been applied predominantly to single adults, they have also been the most likely to try to cross multiple times. From April through September 2020, 47 percent of all single adults encountered by Border Patrol had been encountered in the previous 12 months—more than double the pre-Title 42 rate of 23 percent from 2014 through March 2020. As a result, the number of encounters of Mexican migrants, particularly single adults, has increased (see Figure 2). Between April and September 2020, 48 percent of CBP encounters of Mexicans were of individuals who had previously been caught trying to cross the border without authorization, compared to 30 percent from 2014 through March 2020. While the number of crossings was highest for Mexican nationals, authorities have also encountered more single adults from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. In fact, the increase in repeat crossings was even more pronounced for citizens of these countries, from 7 percent from 2014 through March 2020 to 37 percent from April through September 2020.

Figure 2. U.S. Border Patrol Encounters of Unauthorized Mexican Migrants at the Southwest Border and Mexicans’ Share of All Southwest Border Encounters, FY 2000-22

Note: Data for FY 2022 run from October 2021 to February 2022.

Sources: CBP, “U.S. Border Patrol Apprehensions from Mexico and Other than Mexico (FY 2000 - FY 2020),” accessed March 23, 2022, available online; DHS, Border Security Metrics Report (Washington, DC: DHS, 2019), available online; CBP, “U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018,” updated October 23, 2018, available online; CBP, “Southwest Land Border Encounters,” updated March 15, 2022, available online.

Only some of the increase can be attributed to recidivism. Even if only half the encounters of Mexicans in FY 2021 were of first-time crossers, that would still be the highest in a decade. This uptick likely stems from other factors, including declining economic opportunities in Mexico during COVID-19, organized crime, and perceptions of increased chances of getting into the United States.

Varying Treatment and Increased Diversity of Nationalities

All the while, unauthorized migration grew from certain countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. In FY 2021, U.S. border authorities encountered citizens of Brazil, Cuba, Ecuador, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela more than any year since at least FY 2007 (the earliest data available).

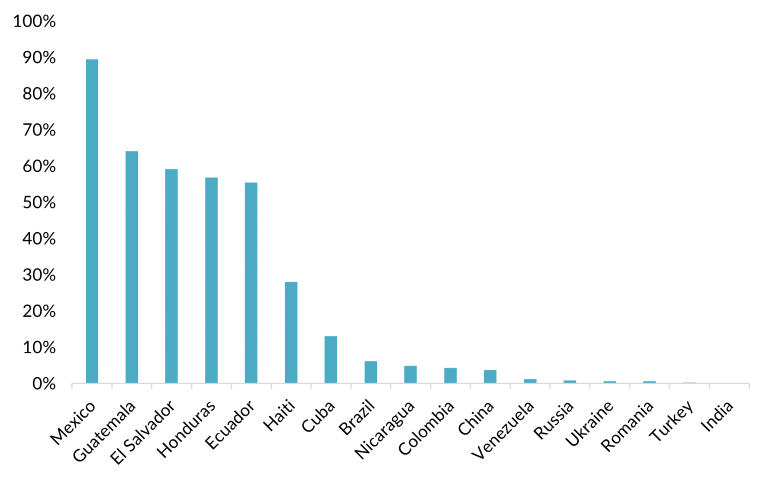

Unauthorized migrants have not all been treated the same under Title 42. Authorities have almost always expelled Mexican single adults and families as well as single adults from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. But treatment of families from these Central American countries has depended on the sector of the border in which they were encountered and the fluctuating resources available to CBP and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Citizens of other countries have been expelled less often. Less than 15 percent of encounters of unauthorized migrants from Brazil, Cuba, and eight other countries led to expulsions between April 2020 and February 2022 (see Figure 3). Of the other nationalities with more than 500 border encounters since Title 42 was enacted and on which CBP releases data, only two had expulsion rates above 15 percent: Haitians (28 percent) and Ecuadorians (55 percent). In general, unauthorized migrants from most countries have been allowed to enter the United States—even if 55 percent of overall unauthorized encounters resulted in expulsions under the Biden administration.

Figure 3. Expulsion Rates of Unauthorized Migrants Encountered at U.S.-Mexico Border by Nationality, April 2020-February 2022

Note: Although CBP also tracks statistics for nationals of Canada, Myanmar, and the Philippines, the sample sizes were not large enough to use for this figure.

Source: CBP, “Nationwide Encounters,” updated March 15, 2022, available online.

Multiple factors account for the varied treatment. For one, Mexico generally will not accept expelled citizens of other countries aside from Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Salvadorans. The U.S. government must either expel them via airplane to their origin countries or place them in removal proceedings inside the United States. Yet expulsions by air are constrained by U.S. capacity and origin-country governments, which may require returning migrants first present a negative COVID-19 test or go through identity verification procedures before travel documents are issued. These delays require ICE to detain migrants for longer periods, but the agency may not have sufficient detention space, particularly for families. Air expulsions also require ICE to transport migrants to the airport and charter planes. Additionally, some Mexican state governments, including in the border state of Tamaulipas, have since January 2021 refused to accept non-Mexican families with children under 7 years old, to which the United States has responded by either expelling them to other Mexican border states or flying them to southern Mexico.

Possible Outcomes When the Expulsions Policy Is Lifted

The end of Title 42 will likely affect recent migration patterns in a number of ways—not least in the scale of migration. Under some scenarios for which DHS is preparing, officials are bracing for as many as 18,000 migrants per day, nearly triple the current pace.

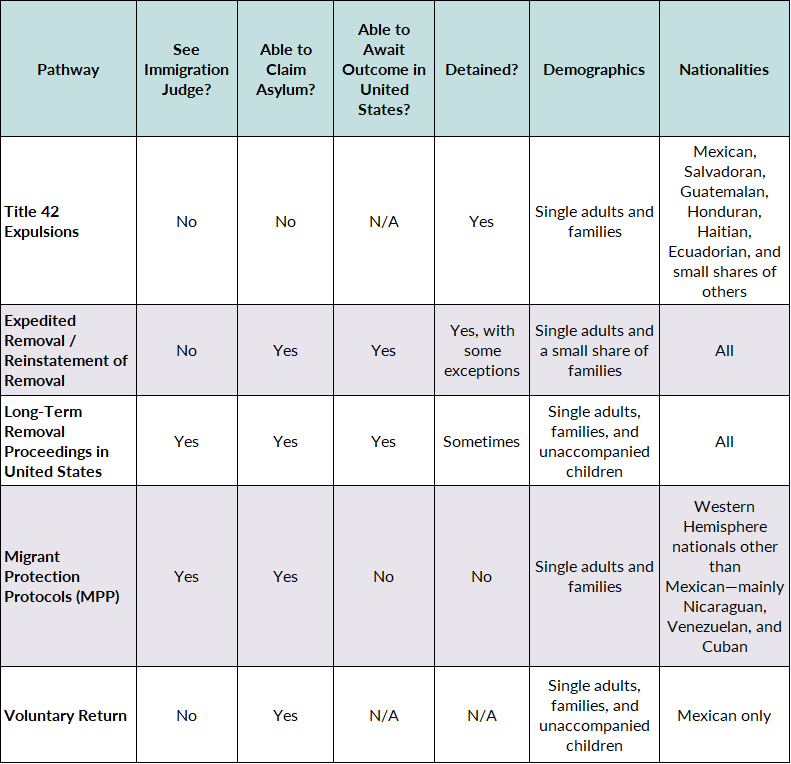

Processing Pathways Available in the Absence of Title 42

Once the expulsions policy is lifted, migrants will again be processed under Title 8 of the U.S. code, which can occur via several pathways (see Table 1). Migrants may be placed in expedited removal, an administrative process wherein a CBP or ICE officer issues an order of removal to a recently arrived unauthorized migrant without a hearing before an immigration judge. Similarly, under reinstatement of removal, a CBP or ICE officer may order removal of someone who re-entered the country unlawfully after having previously been ordered removed. In both cases, however, migrants who claim a fear of persecution or torture in their origin country must be given a credible fear interview by a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) asylum officer, and if they pass, a chance to have an immigration judge hear their asylum or other protection claim.

Table 1. Migrant Processing Pathways at U.S.-Mexico Border

Note: Individuals placed in the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) are in long-term removal proceedings, however this table lists MPP participants as separate from those in long-term removal proceedings in the United States because of the significant differences between experiences in the United States versus in Mexico.

Source: Authors’ analysis.

There is not sufficient ICE detention capacity to place all arriving migrants in expedited removal or reinstatement of removal, particularly because the government cannot hold families for more than 20 days. Most people not placed in expedited removal are entered into long-term removal proceedings in which they receive a notice to appear in immigration court and are either held in detention, released into the United States (sometimes on noncustodial supervision programs called alternatives to detention), or enrolled in the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP, informally known as the Remain in Mexico policy) and released into Mexico to await their hearing. Finally, Mexicans—including single adults, families, and unaccompanied children determined not to be victims of trafficking or at risk of trafficking—may be allowed to voluntarily return to Mexico without going through deportation proceedings.

More Unauthorized Migration, Particularly of Families

In the short term, U.S. officials are bracing for an influx at the border that could surpass even the record-setting numbers of FY 2021. Smugglers and others are likely to promote the narrative that the end of Title 42 will present migrants with their best chance to get into the United States.

Lifting the restrictions will likely lead more families in particular to attempt entry at the border. Currently, many families encountered by border authorities are released into the United States and placed at the end of an immigration court backlog of 1.5 million cases, meaning it might be years before they receive a decision and unlikely they will be removed regardless of the outcome. For those families who had previously been expelled or had feared immediate expulsion, the end of Title 42 may seem like a fresh opportunity to enter the United States.

The Biden administration could rely on MPP for migrants who would have otherwise been expelled under Title 42, such as those from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Yet the administration is fighting in court to end MPP, so it is unlikely to lean too heavily on the Trump-era program. And putting significant new numbers into MPP would place significant pressures on Mexican border communities—a development the government of Mexico likely would only tolerate for so long.

Instead, the Biden administration seems to be working to prevent CBP from being overwhelmed by providing it logistical and administrative support and making more resources available, including enlisting the help of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in planning the response, according to media reports. CBP’s processing capacity will be determinative; officials will need to be able to quickly transport migrants to Border Patrol stations or processing centers and efficiently register migrants’ information and move them along, while maintaining safe and humane conditions. During prior surges, the Border Patrol was quickly overwhelmed and migrants were forced to wait for hours or days in hastily constructed outdoor holding spaces, and children experienced extended stays in CBP custody. Now, the agency is reportedly preparing to build new temporary processing facilities, surge staffing to the border, request vehicles to transfer migrants between border sectors to relieve pressure, and coordinate with other governmental bodies through a joint information center. In the busy Rio Grande Valley, renovations were recently completed on a permanent processing center.

However, it is not clear that these preparations will be sufficient to manage a spike in border crossings that at the high end of the range of DHS scenarios could add up to a record-setting 500,000-plus encounters in one month. This would be a challenge for even the most well-resourced areas of the border; CBP infrastructure in historically less well-traveled border sectors have already been overwhelmed. The Del Rio sector in central Texas and the Yuma sector in western Arizona have experienced more migrant encounters in the first five months of FY 2022 than in any full fiscal year in at least two decades. Large numbers of migrants released from Border Patrol custody in these sectors could quickly swamp the few local organizations that provide assistance to migrants.

In Long Run, Possibility of Fewer Repeat Crossings of Mexicans and Single Adults

Eventually, lifting Title 42 may lead to a decrease of repeated unauthorized crossings and arrivals of single adults, particularly Mexicans, so long as migrants face consequences similar to those used pre-Title 42. Placing single adults in expedited or reinstatement of removal proceedings and carrying out criminal prosecutions have been shown to reduce recidivism.

But these consequences take more time and resources than a Title 42 expulsion or a voluntary return. Expulsion processing can be accomplished in just 15 minutes, whereas expedited removal takes about 90 minutes and criminal prosecution takes even longer because of the need for coordination with U.S. attorneys’ offices and the U.S. Marshals Service. It is not clear whether authorities can apply these consequences uniformly to all single adults, given already high numbers of border crossings and the expected increase. Still, even a gradual return may slowly reduce recidivism.

A New Asylum System at the Border

The success of a new federal regulation that seeks to reduce delays in processing asylum claims made in expedited removal proceedings, while also restoring access to asylum, is intended to have a big impact on the post-Title 42 situation. The rule, based on a proposal by the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), will allow asylum seekers to have their claims adjudicated by USCIS asylum officers in nonadversarial settings instead of the heavily backlogged immigration courts. The rule, published on March 29 in interim final form and effective 60 days later, would also allow DHS to release on parole more migrants in expedited removal, to counteract detention capacity limits.

If implemented and scaled successfully, the new system will provide prompt asylum adjudications that offer protection to people with successful claims and timely removal of those denied asylum. The rule is intended to be phased in over time; DHS’s ability to scale it up will determine its long-term success.

A critical factor in implementing the new system will be the reception process for asylum seekers. One option is to set up short-term reception centers at the border where government agencies such as CBP, ICE, USCIS, the Office of Refugee Resettlement (which handles custody of unaccompanied children), and FEMA can conduct initial registration, custody decisions, and credible fear interviews. This could be done in cooperation with nongovernmental organizations offering legal orientation and possible representation, as well as other support services. Congress in FY 2022 earmarked $200 million for joint processing centers at the border.

Expanding access to legal assistance and representation is key to the efficiency and fairness of the new system. Migrants will need to connect with lawyers or legal service providers during the credible fear process and thereafter. Another concern will be how often asylum seekers are detained versus being monitored through new supervised release programs. Linkages with case management systems would help asylum seekers navigate the system and secure legal representation to ensure appearance at their hearings, receive support in their new communities, and plan for their departure from the United States if their claim is denied.

Whatever its ultimate shape, this new system will be hugely dependent on staffing, which will need to ramp up considerably. As of March 2021, USCIS employed 785 asylum officers; the new rule predicts the agency will need to hire between 794 and 4,647 new officers and staff to process between 75,000 and 300,000 cases annually.

The Role of Regional Partners

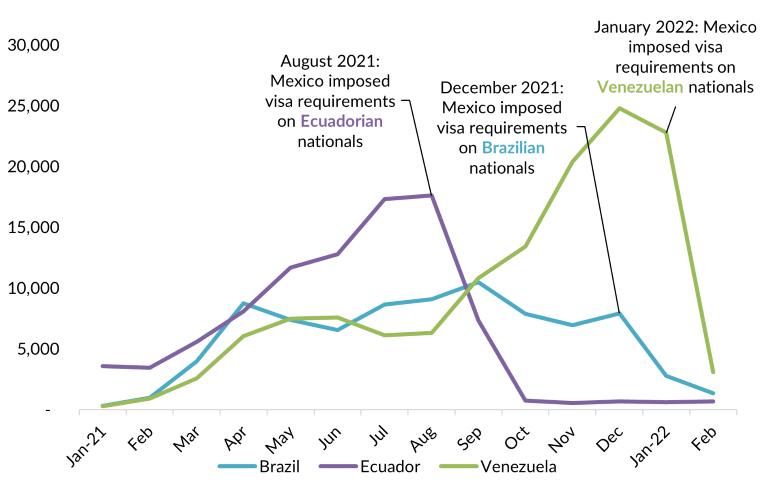

The Biden administration can only do so much; governments outside the United States will also surely impact the post-Title 42 landscape. In the past eight months, Mexico imposed visa requirements for nationals of Ecuador, Brazil, and Venezuela who arrive as tourists, leading to dramatic reductions in arrivals of these nationalities at the U.S.-Mexico border (see Figure 4). However, the most desperate migrants have nonetheless undertaken dangerous journeys through irregular channels. In just the first two months of 2022, 2,500 Venezuelans crossed the treacherous Darién Gap from Colombia into Panama—nearly as many as the 2,800 who crossed in all of 2021—many of them likely headed to Mexico and, ultimately, the United States.

Figure 4. CBP Encounters of Brazilians, Ecuadorians, and Venezuelans at the U.S.-Mexico Border, January 2021-February 2022

Source: CBP, “Nationwide Encounters,” updated March 15, 2022, available online.

Mexican authorities have also increased migrant apprehensions, reaching record numbers of arrests in August, September, and October 2021. It has also become more difficult for migrants to move through Mexico to the U.S. border, due to immigration checkpoints that aim to prevent irregular movement out of the southern border state of Chiapas. Moreover, Mexico’s pace of adjudicating the asylum and humanitarian visa applications of those waiting in the south of the country—which, if granted, allow migrants to move north—has been glacial. After the end of Title 42, the United States may rely on Mexico for immigration enforcement even more.

Farther south, the administration has been working with other countries to stem irregular migration, resulting in increased immigration enforcement in some parts of Central America. Costa Rica in February began requiring visas for Venezuelans, Cubans, and Nicaraguans; and Panama in March imposed visa requirements for Cubans. In March, the United States and Costa Rica signed a memorandum of understanding that commits to strengthening Costa Rica’s migration and border police and integration programs for asylum seekers and refugees. After meeting with Colombia’s President Ivan Duque, Biden in March announced his intention to sign a regional declaration on migration at the Summit of the Americas in June.

A Critical Moment

Both the Trump and Biden administrations insisted Title 42 is a public-health policy, not an immigration one. Nevertheless, its effects on U.S. immigration patterns and the treatment of migrants have been profound. It has resulted in more than 1.7 million expulsions yet relied on a patchwork and seemingly arbitrary system to select those expelled, based on factors such as the operational capacity of CBP and ICE and Mexican policies for receiving expelled migrants. In the process it reduced penalties for repeat crossers, particularly single adults.

Ending expulsions will force the administration to focus on overdue but necessary reforms at the border. Successor policies to Title 42 could provide for efficient adjudication of asylum and other humanitarian protection claims. Although the government is bracing for a surge in arrivals, over the long term ending the policy could remove incentives for repeated unauthorized border crossings and return to pre-Title 42 levels of arrivals.

However, the decision by CDC Director Rochelle Walensky to terminate Title 42 will not likely be the final word on the expulsions policy. If the recent past offers any indication, Republican state officials may sue to block its termination. Those in Texas, for example, have filed seven lawsuits challenging the Biden administration’s immigration policy changes, and secured wins in four. In the coming months, a new battle over Title 42 may arise in the courts.

Sources

Capps, Randy, Faye Hipsman, and Doris Meissner. 2017. Advances in U.S.-Mexico Border Enforcement: A Review of the Consequence Delivery System. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

Capps, Randy, Doris Meissner, Ariel G. Ruiz Soto, Jessica Bolter, and Sarah Pierce. 2019. From Control to Crisis: Changing Trends and Policies Reshaping U.S.-Mexico Border Enforcement. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

Executive Office for Immigration Review. 2022. Pending Cases, New Cases, and Total Completions. Updated January 19, 2022. Available online.

Flores, Adolfo and Hamed Aleaziz. 2021. Border Agents in Texas Have Started Releasing Some Immigrant Families after Mexico Refused to Take Them Back. BuzzFeed News, February 6, 2021. Available online.

Fossum, Sam and Maegan Vazquez. 2022. US Will Designate Colombia as a Major Non-NATO Ally, Biden Says. CNN, March 10, 2022. Available online.

García, Uriel J. 2022. Trump Appointees Are Helping Texas Derail Biden’s Immigration Agenda. The Texas Tribune, March 15, 2022. Available online.

Gonzalez-Barrera, Ana. 2021. Before COVID-19, More Mexicans Came to the U.S. than Left for Mexico for the First Time in Years. Pew Research Center Fact Tank blog post, July 9, 2021. Available online.

Harrington, Ben. 2021. The Law of Asylum Procedure at the Border: Statutes and Agency Implementation. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Meissner, Doris, Faye Hipsman, and T. Alexander Aleinikoff. 2018. The U.S. Asylum System in Crisis: Charting a Way Forward. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

Menendez, Senator Bob. 2022. Menendez, Schumer, Booker and Padilla Joint Statement on Recent Court Decisions on Title 42. Press release, March 5, 2022. Available online.

Mexican Government. N.d. Extranjeros presentados y devueltos, 2021—Cuadro 3.1.1. Accessed March 23, 2022. Available online.

Miroff, Nick and Maria Sacchetti. 2022. Biden Faces Influx of Migrants at the Border Amid Calls to Lift Limits that Aided Expulsions. The Washington Post, March 24, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Biden Officials Bracing for Unprecedented Strains at Mexico Border if Pandemic Restrictions Lifted. The Washington Post, March 30, 2022. Available online.

Morrissey, Kate. 2021. Mexico Pressures Asylum Seekers to Stay for Months at Its Southern Border. Los Angeles Times, December 22, 2021. Available online.

Moskowitz, Alan and James Lee. N.d. Immigration Enforcement Actions: 2020. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Available online.

Murillo, Alvaro. 2022. Costa Rica Imposes Visa Requirements for Venezuelans as Migration Surges. Reuters, February 17, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Costa Rica Says Will Work with U.S. to Strengthen Migration Control. Reuters, March 16, 2022. Available online.

Nancy Gimena Huisha-Huisha and her Minor Child et al. v. Alejandro N. Mayorkas et al. 2022. No. 21-5200. U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, March 4, 2022. Available online.

Rosenberg, Mica, Ted Hesson, and Mimi Dwyer. 2021. Expulsions, Releases, Hotels: Migrant Families at U.S.-Mexico Border Face Mixed U.S. Policies. Reuters, March 23, 2021. Available online.

Sanchez, Sandra. 2022. Documents: Permanent Joint Processing Centers to Expedite Asylum Claims, Replace Costly Tents. Border Report, March 22, 2022. Available online.

Singer, Audrey. 2021. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) COVID-19 Policies and Protocols at the Southwest Border. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

State of Texas v. Joseph R. Biden Jr. et al. 2022. No. 4:21-cv-0579-P. U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, March 4, 2022. Available online.

Swan, Jonathan and Stef W. Kight. 2022. Scoop: Biden Officials Fear “Mass Migration Event” if COVID Policies End. Axios, March 17, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Public Health Reassessment and Order Suspending the Right to Introduce Certain Persons from Countries Where a Quarantinable Communicable Disease Exists. Federal Register 86, no. 148. August 5, 2021. Available online.

---. 2022. Public Health Determination and Order Regarding the Right to Introduce Certain Persons from Countries Where a Quarantinable Communicable Disease Exists. Final order, April 1, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection. 2022. Nationwide Encounters. Updated March 15, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020. Control of Communicable Diseases; Foreign Quarantine: Suspension of Introduction of Persons into United States from Designated Foreign Countries or Places for Public Health Purposes. Federal Register 85, no. 57. March 24, 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. Order Suspending Introduction of Persons from a Country where a Communicable Disease Exists. Federal Register 85, no. 57. March 24, 2020. Available online.