You are here

Trump Administration’s New Indefinite Family Detention Policy: Deterrence Not Guaranteed

Families Belong Together day of action in Houston. (Photo: Jill_Ion/Flickr)

Having shelved a controversial family-separation practice that drew massive protest—and did not slow the arrival of Central American families at the U.S.-Mexico border—the Trump administration is proposing a new tactic: Indefinite detention of parents and children.

With a proposed regulation introduced September 7, the administration is seeking to terminate the landmark 1997 Flores settlement, which for more than two decades has provided critical protections for children in U.S. immigration custody. While the U.S. government has generally been limited to detaining families for 20 days, the proposed regulation would allow President Trump to fulfill his oft-repeated goal of holding families in detention until the conclusion of their immigration hearings.

The administration would accomplish this by implementing an action provided for in a 2001 court order that incorporated the understanding of all parties in Flores: That the agreement itself would terminate 45 days after the U.S. government publishes final regulations implementing it. While the Bush and Obama administrations did not issue a regulation, the Trump administration is moving forward, essentially proposing to significantly narrow the Flores protections, through its interpretation of the court settlement. The result, undoubtedly, will be new litigation.

This policy on family detention, like the brief foray into family separation that was a result of the administration’s zero-tolerance policy ordering the prosecution of all illegal border crossers, is intended to deter future unauthorized arrivals, including asylum seekers. Yet there is little to suggest the policy will have the deterrent effect the administration is seeking. While both detention and prosecution have been used by past administrations with some success to deter unauthorized flows of economic migrants, there is scant evidence that these would achieve similar outcomes with respect to today’s arrivals of families and children from Central America, often driven by the desire to escape violence.

Apprehensions at the Southwest Border: Flows Little Deterred by Policy

Indeed, the most recent numbers on apprehensions at the southern border offer evidence to the contrary. Despite the administration’s efforts to deter arrivals, apprehensions of illegal border crossers more generally are on track with seasonal patterns of recent years, in some cases even higher. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) apprehensions this year show one of the highest increases from July to August in nearly two decades, with a 20 percent end-of-summer increase.

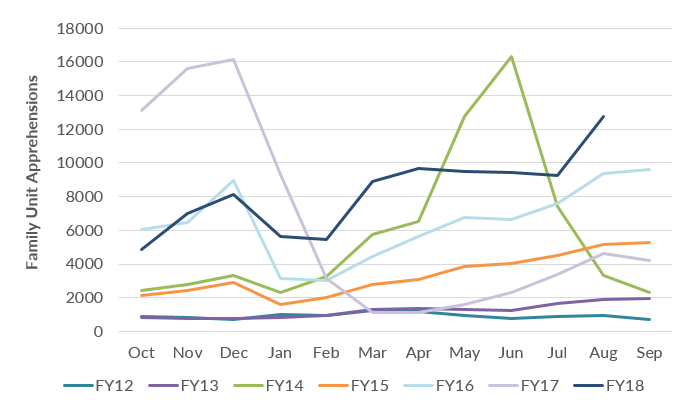

In the immediate aftermath of Donald Trump’s election—in which coverage of his hardline immigration agenda dominated the news—there was a decline in apprehensions. This phenomenon, referred to as the Trump effect, persisted during his first months in office, with fiscal 2017 posting lows in apprehensions unseen in nearly half a century. In 2018, apprehensions have returned to levels and seasonal patterns seen in years past, but with an especially strong increase among family units (the term used by CBP for one or more parents traveling with a child), even as compared to unaccompanied children or individual adults.

In August, CBP apprehended 4,396 unaccompanied children, a 12 percent increase from the 3,938 intercepted in July. So far this fiscal year, CBP has apprehended 45,915 unaccompanied children, already more than were encountered during the entire 2017 fiscal year (41,546), but still short of the level seen in FY 2016 (59,757).

However, family unit apprehensions surged 38 percent from July to August, to 12,774—the biggest increase between the two months since CBP started publishing data on family apprehensions in 2012. So far this year, there have been 90,607 family unit apprehensions, already the highest number ever. The next highest was 77,674 in FY 2016.

Figure 1. Monthly Family Unit Apprehensions at U.S.-Mexico Border, FY 2012-18*

* The FY 2018 numbers span the first 11 months of the fiscal year.

Sources: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “United States Border Patrol Southwest Family Unit Subject and Unaccompanied Children Apprehensions Fiscal Year 2016,” updated October 18, 2016, available online; CBP, “Total Family Unit Apprehensions by Month,” accessed September 21, 2018, available online; CBP, “Southwest Border Migration FY 2018,” updated September 20, 2018, available online.

Applying Standard Deterrence Tactics to a Different Population

Deterrence has been the guiding strategy of U.S. border security for decades. In 1994 the Clinton administration introduced the strategy of “deterrence through prevention,” which initiated a multiyear build-up of border enforcement resources and infrastructure. During the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations, the Border Patrol began imposing “consequences” intended to raise the practical, psychological, and financial costs of illegally crossing the border. These consequences included returning Mexican crossers to locations far from where they were apprehended, increasing the use of formal deportations rather than simply turning people around at the border, and prosecuting individuals criminally for immigration offenses.

The most significant consequence began in 2005 when DHS introduced Operation Streamline. Under the program, magistrate courts started hearing criminal immigration cases en masse, with as many as 50 to 100 people appearing before a judge at once. Many judges, defense attorneys, and advocates have criticized this practice as grossly violative of due-process rights. In the past, DHS exempted categories of border crossers from prosecution, including juveniles, parents traveling with minor children, asylum seekers, and those with certain health conditions.

The Border Patrol’s deterrence strategies did appear to decrease overall illegal crossings. Apprehensions plummeted between 2000 and 2016 from 1.6 million to just over 400,000. And the number of people trying to cross the border more than once also declined, with the recidivism rate falling from 29 percent in 2007 to 14 percent in 2014. A number of other factors undoubtedly also contributed significantly to the decline in attempted illegal crossings, including historic improvements in Mexico’s economy and education system, its declining birthrates, and lessened workforce needs in the United States following the 2008-09 recession.

These deterrence strategies were directed, however, at populations traditionally associated with illegal crossings: young adults from Mexico. They do not seem to equally apply to today’s arrivals, which include humanitarian migrants facing intense pressure to flee. Nor does the existing immigration system appear to be designed to address the particular characteristics of these new flows. A recent DHS report concluded precisely that: the U.S. immigration enforcement regime is “especially well designed to repatriate single adults from Mexico and aliens who have been previously convicted of a crime” and is “less well designed to quickly repatriate—or to adjudicate claims for relief for" other groups, including unaccompanied children, family units, and asylum seekers.

Prosecuting Illegal Entry

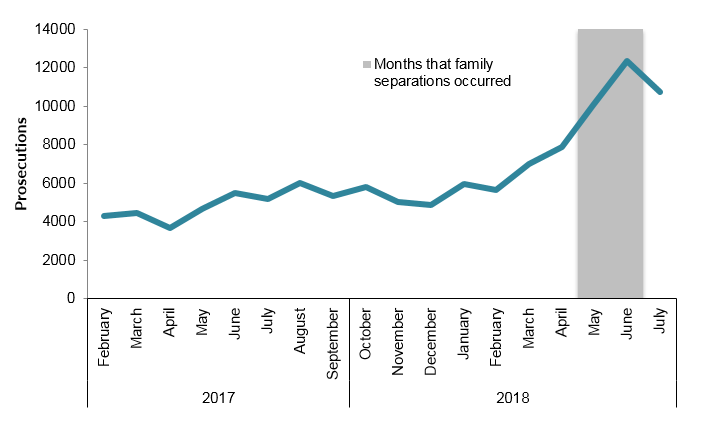

Of all the deterrence strategies employed by the Trump administration, the one that has received the most attention is the “zero-tolerance” policy, which inevitably led to separation of families because children cannot be held in criminal detention. Faced with huge backlash after separating more than 2,500 children from their parents—some 182 had yet to be reunited, at this writing, with parents who were deported—the administration quickly backtracked. Even at the peak of zero tolerance in June, though, just 46 percent of illegal crossers were prosecuted. While the government is no longer separating families, criminal immigration prosecutions of other individuals continue and remain relatively high today.

Figure 2. Immigration-Related Prosecutions, FY 2017-18*

* The FY 2017 numbers span the last eight months of the fiscal year; the FY 2018 numbers span the first 11 months.

Sources: TRAC Immigration, “TRAC Data Interpreter: Prosecutions,” multiple reports, available online.

The administration admitted early on that deterrence was the goal of the zero-tolerance policy, although it later denied that as a motivating factor. However, the Intercept on September 25 published an article quoting from a redacted April 23 memo to Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, which she later signed, making clear the administration selected the prosecution of adults, including those with children, as the option that would have “the greatest impact on flows.”

Rising and More Detention

The administration has been forthright about its plans to detain all apprehended migrants, including families, children, and asylum seekers, until the conclusion of their immigration proceedings. In addition to the new measures to detain families under the proposed Flores regulation, the President has issued two executive orders and a presidential memo that seek to end “catch and release,” the term he uses to describe the release of those intercepted by CBP—whether crossing illegally or presenting at ports of entry to request humanitarian protection. Just recently, Attorney General Jeff Sessions indicated he may revoke the ability of asylum seekers to bond out of detention while they await a long-off hearing—a change that could significantly increase the number held in prolonged detention.

In prior administrations, families and children were largely exempt from detention. Typically, the majority of immigrants apprehended at the border were detained and subject to swift removal to their country of origin via expedited removal, reinstatement of a prior removal order, or voluntary return. The exception were unaccompanied children and most asylum seekers, including families: under a variety of laws and policies they are not generally detained during their removal proceedings.

The Trump administration wants to change that. However, its desire to detain this traditionally exempted group—unaccompanied children, families, and asylum seekers—has met two obstacles: legal hurdles and limited resources.

Flores Regulation

Under the 1997 Flores settlement, the government is obliged to maintain certain standards of care when detaining children: detention in the least restrictive setting, release to parents or other sponsors when possible, and transfer to state licensed facilities when not.

In 2015, U.S. District Judge Dolly Gee ruled that the Flores standards applied also to accompanied children, i.e. children in family units. The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed her ruling in 2016.

Gee had also said that the government may take up to 20 days to transfer children to “state-licensed facilities.” However, because states do not hold any families in detention and thus do not have licensing procedures for family detention facilities, this 20-day requirement also became the de facto limit for family detention.

The administration’s proposed regulation to implement Flores would get around this 20-day limit by attempting to effectively create a self-licensing scheme. Under the proposed regulation, the government could hold children in federally licensed facilities. Any facility would be considered federally licensed if it abides by ICE’s Family Residential Standards and is audited by a DHS contractor—a requirement that all DHS family residential facilities already meet.

Increasing Detention Space

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) immigrant detention capacity is determined by congressional authorization. In FY 2018, ICE requested an additional $1.24 billion to support 48,879 adult beds and 2,500 family beds. Congress authorized spending for 38,020 adult beds.

Despite a congressional warning to ICE not to exceed its budgeted detention capacity, the agency has been detaining an average daily population of 40,379 adult detainees—or 2,359 beds over its appropriated level. To make up for the difference, DHS has circumvented the appropriations process by transferring $200 million from various other DHS agencies, including nearly $10 million from FEMA.

For FY 2019, ICE has requested funding to detain an average daily population of 49,500 adults and 2,500 family members, at a total of $2.76 billion.

In addition to seeking appropriations for adult detention, the Trump administration has also sought out more space in which to detain growing numbers of unaccompanied children. Unaccompanied child migrants are minors mostly from noncontiguous countries (usually those in Central America) who arrive at the southern border without a parent or legal guardian. Under a 2008 law, these children are placed into the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and are placed in long-term removal proceedings. ORR releases the children to an adult sponsor in the United States (a relative or family friend) if one volunteers, and if not, to a foster family; otherwise, the children are held in an ORR shelter. This month it was reported that more than13,300 unaccompanied children—a record number— are in the custody of ORR.

This is largely due to a decrease in the discharge rate from shelters. This may be due to fewer sponsors coming forward and to a lengthier and more difficult process for receiving approval. In addition, critics argue this is the result of a new ORR policy to fingerprint all household members in a potential sponsor’s home and share that information with ICE. The fact that ICE recently arrested 41 unauthorized immigrants as a result of this information sharing reinforces the perception that it is not safe to come forward.

On September 11, HHS announced its intention to triple the size of a temporary “tent city” detention center in Tornillo, Texas to house up to 3,800 children. Some $266 million in funding to increase shelter capacity will come from a number of other HHS programs, including Head Start, HIV prevention programs, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Even if the administration is able to finalize the Flores regulations in the face of legal challenges and meet the subsequent resource constraints around detention bed space, another legal issue will likely arise, one first encountered by President Obama. After a sharp spike in the arrival of unaccompanied child migrants and families in spring 2014, the Obama administration began detaining families on a large scale. A federal district court in Washington, DC threw a wrench in that plan when it issued a preliminary injunction preventing ICE from considering the goal of “general deterrence” when deciding whether to detain families. The case was never fully adjudicated because the Obama administration reversed course before the litigation could move forward.

Thus, before implementing a policy of mass family detention, the Trump administration will most likely have to answer whether the proposed regulation actually implements the Flores settlement or does something different, and whether the intention of the policy is deterrence, and if so, whether that is lawful.

- 1997 stipulated settlement agreement in Flores v. Reno

- Proposed Trump administration regulation implementing the Flores agreement

- Executive Order 13767, Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements

- MPI brief examining the border security executive order

- Presidential Memorandum of April 6, 2018 ending “catch and release”

- DHS Report, 2014 Southwest Border Encounters: Three-Year Cohort Outcomes Analysis

- Vox article, “Why Trump is threatening to veto the omnibus bill over immigration”

- MPI op-ed in Vox: “Family separation isn’t just immoral. It’s likely ineffective.”

- Department of Homeland Security FY 2018 reprogramming of funds notification

- Letter from Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar to Senator Patty Murray, explaining HHS’s reallocation of funds

- Opinion granting a preliminary injunction against the Obama administration detention policy, in RILR v. Johnson

- Intercept article citing DHS memorandum on zero-tolerance as a deterrent

National Policy Beat in Brief

U.S. Introduces Measures to Reduce Low-Income Immigration. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) on September 25 published the draft of a proposed regulation that would potentially significantly reduce the number of foreign nationals coming to the United States and receiving permanent residency, or green cards. While current law says the U.S. government may exclude foreign nationals who are or are likely to become public charges, the proposed regulation defines these specifically as someone who receives one or more of certain listed public benefits. To determine whether to deny a green card or short-term stay based on a likelihood that someone will become a public charge, the proposed regulation directs USCIS officers to weigh a number of factors, including the applicant’s income, level of education, health, family size, and past benefits use. The proposed regulation does not affect current green-card holders, but would require a public-charge test for already present noncitizens seeking to get a green card or permission to stay short term. The Department of State is likely to issue a corresponding regulation that will apply to issuance of both immigrant and nonimmigrant visas.

Even though most immigrants who qualify for public benefits would not be affected by the regulation, it is likely to have a chilling effect on benefits use by both immigrants and their U.S.-citizen relatives. Indeed, according to service providers, rumors surrounding preliminary drafts leaked in 2017 and earlier this year have reduced the number of immigrants coming forward to receive benefits such as federal nutritional programs for children and expecting mothers.

- Proposed DHS rule, Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds

- Washington Post article on the draft regulation

- MPI commentary on the public-charge rule’s possible impact on future legal immigration

Trump Administration Proposes Record-Low Ceiling on Refugee Admissions; Earns Congressional Ire over Lack of Consultation. The Trump administration announced it will reduce the maximum number of refugees who will be admitted for resettlement in the United States in fiscal year (FY) 2019 to 30,000. Each year before finalizing the refugee ceiling, the President is obligated to consult with Congress. After the administration’s announcement, congressional leaders in both parties vigorously complained that the President had failed to do so two years in a row. The administration then backtracked and stated the 30,000 number is a proposal, and that the State Department will meet with congressional leaders before announcing the final figure later this month.

The administration’s proposed ceiling would be the lowest since the refugee resettlement program formally began in 1980. In FY 2017, President Trump lowered the ceiling from 110,000, previously designated by President Barack Obama, to a then-record low of 50,000. In FY 2018, the administration lowered the ceiling to 45,000. Because of newly added vetting procedures and a decrease in staff working on refugee applications, the final number of admitted refugees for FY 2018 will be much lower: as of September 19, 21,286 refugees had been admitted.

- Secretary of State Mike Pompeo remarks on the proposed ceiling

- Voice of America article on the State Department’s intention to consult with Congress

- MPI data tool on U.S. refugee admissions and ceilings by year since 1980

Settlement in Family Reunification Case May Give Some Parents a Second Chance at Asylum. The Trump administration and lawyers representing immigrant families separated at the border have reached a settlement that may allow more than 1,000 parents a second chance at staying in the United States. If approved by the court overseeing the litigation, some parents and their children would get a second chance to apply for asylum, even if U.S. authorities had previously rejected their claims. The settlement provides no immigration benefits to parents who have already been deported, but does leave the possibility that some could return in “rare and unusual” cases.

The settlement stems from three lawsuits, in which it was alleged that many parents failed their initial “credible-fear” asylum interview because they were suffering extreme trauma from the forced separation with their children. The judge overseeing the case indicated that he is inclined to approve the settlement.

- Negotiated agreement between the Department of Justice and immigrant families

- Vox article on the settlement agreement

Attorney General Continues to Reshape the Immigration Court System. Attorney General Jeff Sessions has referred two additional immigration court decisions to himself. In one case, he vacated a Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) decision, ruling that immigration judges have no inherent authority to terminate or dismiss removal proceedings. This decision will have a significant impact on the outcome of immigration cases, as about 15 percent of immigration court cases end in termination. In the other case, Sessions stayed a BIA decision while he reviews briefs to help him decide whether immigration judges may hold bond hearings for detained asylum seekers.

As the head of the immigration court system, the Attorney General can refer final decisions from the BIA to himself and issue new decisions, which may overturn the appellate board’s prior decision. Sessions has already used this referral and review power four times this year.

- Reuters article on the Attorney General’s decision to limit the ability of immigration judges to terminate cases

- Attorney General notification of referral and decision in Matter of S-O-G- & F-D-B-

- Attorney General notification of referral in Matter of M-G-G-

Federal Judge Declines to Enjoin DACA. U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen decided against issuing a preliminary injunction on the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which the Obama administration launched in 2012 to offer work authorization and relief from deportation to qualified unauthorized immigrants brought to the country as minors. A group of six states, led by Texas, brought a lawsuit in May 2018 arguing that DACA was an unlawful use of executive power. Hanen, who in 2015 found unlawful the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA) program and a DACA expansion, wrote that while he found merit in Texas’s argument that DACA was unlawful, he ruled against granting the injunction because the states had delayed seeking the relief for years and because an injunction would be far more disruptive than maintaining the status quo. Texas and the other state litigants have asked Hanen for a final ruling, rather than appeal his decision on the injunction.

The Trump administration attempted to end DACA last year, but three federal judges have prevented that, ruling the administration’s process for ending the program was improper and unlawful. As a result, the administration is obligated to continue adjudicating applications from anyone who has previously been a DACA beneficiary.

- Interlocutory Appeal Order in Texas v. USA

- National Immigration Law Center page on the status of current DACA litigation

- Bloomberg article on the states’ decision not to appeal the injunction denial

Foreign Born Are Highest Share of U.S. Population Since 1910. New data from the Census Bureau shows that in 2017 the U.S. foreign-born population was 13.7 percent, the highest share since 1910. The data show a shift in new arrivals: 41 percent of those arriving since 2010 came from Asia, overtaking Latin America. However, the majority of the total foreign-born population is still from Latin America: 50 percent compared to 31 percent from Asia. The data also showed that 45 percent of arrivals since 2010 are college educated, up from about 30 percent of those who arrived between 2000 and 2009.

- New Census Bureau statistics

- New York Times article on the new data

State Policy Beat in Brief

Judge Hampers Federal Crackdown on LA Sanctuary Policies. A federal judge ruled that the Trump administration exceeded its authority when it withheld a 2017 public safety grant from Los Angeles over the city’s refusal to cooperate with immigration authorities. Normally Los Angeles receives more than $1 million in federal funds each year to support local prosecutors and anti-gang programs. But the Justice Department told the city that in order to receive the funding it needed to comply with federal immigration policies, including notifying U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) before releasing a noncitizen from custody. Los Angeles has a longstanding policy of not involving local police in immigration enforcement actions.

- Courthouse News Service article about the case

- Order granting a preliminary injunction in City of Los Angeles v. Jefferson B. Sessions