You are here

Trump Administration’s Unprecedented Actions on Asylum at the Southern Border Hit Legal Roadblock

Processing at the San Ysidro border crossing (Photo: Mani Albrecht/U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

As has become the pattern for most of President Donald Trump’s immigration agenda, a federal judge earlier this month blocked a recently imposed administration measure barring immigrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border illegally from seeking asylum in the United States. The injunction lasts until December 19, when the California-based court will hold a hearing on a more permanent bar. Seeking to move the case more quickly through the appellate process and likely Supreme Court review, the Justice Department filed a notice Tuesday that it would appeal U.S. District Judge Jon Tigar’s restraining order to the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The administration’s desired asylum changes are part of a series of high-profile actions undertaken in response to several caravans of Central Americans making their way through Mexico to the U.S. border. In the lead-up to the midterm elections and after terming the caravans an “invasion,” Trump dispatched thousands of active-duty soldiers to the border and ordered the hardening of U.S. ports of entry with barbed wire and vehicular barriers. In a much-criticized action earlier this week, Border Patrol agents fired tear gas and rubber bullets at several hundred caravan members, including mothers and toddlers, while they were rushing the border at San Ysidro. The Mexican government has brought an action to challenge the legality of the tear gas.

The administration has justified its hardline policies as necessary to deter the arrival of Central Americans at the border and speed removal hearings for those already in the United States who are seeking asylum. Concerned by rising humanitarian protection claims at the border, the administration has gone to great lengths to limit access to asylum there, both during preliminary interviews as well as in immigration court hearings later in the process.

The Attempted Asylum Changes

Under the now temporarily enjoined changes, migrants apprehended in between ports of entry would be ineligible to apply for asylum. While the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has made clear that migrants seeking protection must apply at ports of entry, few asylum claims are permitted each day at official crossings, causing thousands to mass in Tijuana waiting for weeks at a time until their turn comes up. In some cases, perhaps to bypass such lines, many Central American families and unaccompanied minors have crossed between ports of entry and then sought out Border Patrol agents to make a protection claim.

Under the administration’s plan, which was in place for nine days before being temporarily halted, migrants crossing between ports of entry and expressing a fear of returning home would still be referred to a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) asylum officer for a preliminary interview. However, unlike past practice, the interview would be to determine whether the applicant has a “reasonable fear” of persecution if returned to the home country rather than a “credible fear”—which requires a lower standard of proof. More importantly, applicants who convince asylum officers that there is a reasonable possibility they would be persecuted or tortured could only apply for withholding of removal or similar grant under the Convention Against Torture rather than for permanent asylum. A total of 107 migrants faced this new process before the asylum changes were blocked.

Beyond having a higher evidentiary threshold, withholding of removal could hypothetically be withdrawn in the future and does not confer as many benefits as asylum does. To receive withholding, the applicant must establish that it is “more likely” than not that his or her life or freedom would be threatened, a clearly higher standard than asylum, where courts have generally held that a fear may be well founded if there is as little as a 10 percent chance of persecution; withholding of removal applicants must prove that there is more than a 50 percent chance of persecution if returned.

However, while the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) mandates that withholding or deferral must be granted to qualifying applicants, the government has far more discretion to grant or deny asylum. Someone who qualifies for asylum under every statutory ground could still be ultimately denied as part of an exercise of discretion.

While recipients of withholding of removal are eligible to apply annually for work authorization, their status, unlike for asylum seekers, does not also apply to eligible family members, meaning spouses or children would have to independently qualify. Withholding also does not lead to lawful permanent residence and ultimately citizenship.

The Legal Case Ahead

The case that challenged the new asylum policies and resulted in enjoinment, East Bay Sanctuary v. Trump, will likely next be heard by the Ninth Circuit, since the government has given notice of intent to appeal the judge’s current order.

Given the Ninth Circuit’s past history, the appellate court is likely to affirm Tigar’s order, holding the pause in place. The administration could then appeal to the Supreme Court, which could take up the case for review in its current term that ends in June 2019 or in its next term in the fall of 2019.

It is also possible that there may be further litigation raising similar or other claims. For example, a number of potential international legal issues could surface. The 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees ensure the rights of asylum seekers to seek protection regardless whether they entered a country legally or not. Challenges might also be raised around the question of whether the more limited grant of withholding of removal fulfills U.S. international obligations towards asylum seekers.

Realistically, however, the most severe consequence for failing to uphold these standards would be a statement by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) denouncing the actions as violating international law. Yet the United States provides more than 40 percent of its funding—meaning UNHCR would have to think carefully before sanctioning its biggest contributor.

Broader Changes in Asylum Policy

After failed attempts to have Congress close what Trump and Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen describe with frustration as “loopholes” in the asylum system—while others note these are protections enshrined in federal law or the result of lack of massive new detention capacity at the border—the administration has unilaterally attempted to change the asylum rules. The enjoined changes represent just one of those efforts. There are many more.

Speeding Asylum Applications

The same day Tigar issued his ruling temporarily blocking the new asylum policies, the administration published its plan to speed up asylum adjudications. Under a new Justice Department directive, immigration judges are obligated to complete all asylum adjudications within 180 days. The memo from the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) instructs judges to only go beyond the 180-day limit if there is “good cause” and “exceptional circumstances” for the delay. It is not clear how this policy will apply to the hundreds of thousands of asylum cases already pending before the courts—part of a massive overall backlog of 1 million cases.

In addition, the administration last week set up ten fast-tracked docket immigration courts across the United States to complete within one year all cases of migrant families arriving at the border.

Expediting such a large portion of the immigration court’s caseload will be a momentous task, considering hearings on new cases are currently being scheduled for 2022. If accelerated processing works, it will inevitably result in increased denials of asylum claims and deportation of failed asylum seekers. The administration is hoping that such outcome will deter future asylum seekers from even trying to make it to the United States.

Limiting Asylum Applications at the Border

The Trump administration has not sought to change the process for migrants who apply at ports of entry. However, it has been alleged that DHS is purposefully slowing asylum intakes at border ports of entry. In the Al Otro Lado v. Nielsen lawsuit brought in federal court in California, the plaintiffs, including several would-be asylum seekers turned back at ports of entry, have alleged the existence of a policy in place since at least 2016 of metering the number of asylum seekers. For example, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers at a number of border ports will turn asylum seekers back before they reach the official crossing, forcing the foreign nationals to wait days, weeks, or even months in Mexico before they can return to apply for asylum. Recent media reports suggest that more than 5,000 asylum seekers are waiting in such a process outside the San Ysidro port of entry where the Border Patrol clashed this week with some migrants from the caravan.

As a part of the East Bay Sanctuary lawsuit, it has also come to light that this metering practice has been applied to unaccompanied child migrants as well. Under the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008, unaccompanied child migrants from countries other than Mexico and Canada must be granted immediate protection in the United States. Upon apprehension in between ports of entry or arrival at a port of entry, these children are required to be transferred to the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement and given the opportunity to apply for asylum before a USCIS asylum officer. However, according to a declaration submitted in the East Bay Sanctuary lawsuit and other reports, Mexican authorities have blocked unaccompanied children from approaching U.S. ports of entry and even threatened them if they add their names to the list of those seeking U.S. asylum.

While not necessarily directly limiting asylum applications, the administration is also doing everything it can to harden the border. The President ordered the unprecedented deployment of 5,800 active-duty troops to the southern border—a step well beyond earlier deployments of National Guard members by this and prior administrations. The actions come at a high cost. According to one estimate, the deployment, combined with the presence of the more than 2,000 National Guardsmen already at the border, could cost in excess of $200 million.

Changing the Legal Definition of Asylum

In addition to limiting how many people can apply for asylum at the border and speeding the adjudications of those in the United States, the administration has narrowed the legal definition of who qualifies for asylum. In June 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions availed himself of his authority over the immigration courts to sharply limit instances in which applicants fearing domestic or gang violence could claim asylum—disregarding decades of evolving case law. The move particularly affects the viability of asylum claims made by Central Americans, who often cite those grounds.

However, despite sharp language in the Sessions order (including a statement that going forward generally victims of domestic or gang violence “will not qualify for asylum”), it is not clear whether the decision has actually affected asylum adjudications.

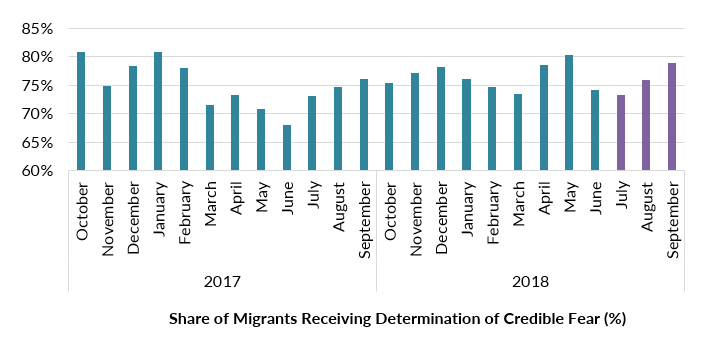

The proportion of migrants who receive a determination of credible fear during a preliminary interview with USCIS asylum officers remains high, at nearly 80 percent in September 2018.

Figure 1. Credible Fear Found During Initial Interview, FY 2017-18

Note: The months shaded purple are those during and after which asylum officers received guidance on the Attorney General’s ruling sharply limiting consideration of gang and domestic violence as grounds for protection.

Sources: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), “Credible Fear and Reasonable Fear Statistics and Nationality Report,” multiple reports, available online.

Meanwhile the asylum grant rate by immigration judges is at a nearly 20-year low, down to a 33 percent approval rate in fiscal year (FY) 2018. However, it is not clear what has caused this downward trend.

Figure 2. Asylum Grants Before Immigration Judges, FY 1996-2018

Note: “Share Approved” is calculated by dividing the number of approvals by the total of both the numbers approved and denied.

Sources: Justice Department, Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), “Statistics Yearbook,” multiple reports, available online; EOIR, “Asylum Decision Rates,” October 2018, available online.

More Changes?

The administration has signaled a number of other potential changes on asylum. Before resigning, Sessions referred two cases to himself that will likely be decided by his successor. In Matter of M-S-, Sessions was considering whether judges can hold bond hearings for detained asylum seekers. Ending their ability to do so would increase the number of detained asylum seekers.

In Matter of Negusie, Sessions was weighing whether to limit asylum in another area. Applicants who have a history of engaging in persecution are barred from receiving asylum under current law. But if the applicants can prove they assisted in such persecution under duress, they may not be barred. Sessions had indicated his intention to review this “duress” defense.

In a preview of upcoming regulatory changes, DHS indicated it will introduce changes to the work authorization process for asylum applicants, as a means of deterring unwarranted asylum filings. Perhaps most importantly, DHS intends to publish a regulation requiring asylum seekers to wait for their U.S. immigration court hearings in Mexico—a move first alluded to in a Trump executive order signed days into his presidency. DHS may be considering fast-tracking this regulation, likely in reaction to the caravans. And even as it proceeds with what could be a unilateral declaration, the administration has been seeking to negotiate a “Remain in Mexico” plan with the administration of incoming Mexican President, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who takes office December 1. Though a deal between the two countries was reported to be on the brink of approval, the situation was far more unclear at this writing.

Implications for Mexico

The Trump administration maintains its problems with asylum could be solved by Mexico, and thus has increasingly placed pressure on the country. The asylum changes outlined in a proclamation Trump signed November 9 ending the possibility of asylum for those crossing between ports of entry did this directly by stating the plan would terminate if Mexico agrees to a safe third country agreement. Under such a deal, asylum seekers arriving at the Southwest border who fail to first apply in Mexico could be pushed back. The proclamation also states that DHS and the State Department will consult with Mexico on efforts to deter, dissuade, and return foreign nationals transiting through Mexico to the U.S. border.

Any actions the administration takes to push asylum seekers back to Mexico or make them wait at ports of entry for prolonged periods also place huge pressure on Mexico. Such pressures have occurred before and cause unrest as civil-society organizations along the border and the Mexican government try to provide for migrants’ needs while maintaining order.

The Haitian Case

Because of an earlier change in U.S. policy on the expedited removal of Haitian nationals, thousands of Haitians applied for asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border in fall 2016. The United States “metered” their asylum applications, forcing—by one count—more than 3,500 Haitian and African migrants to wait in Tijuana and Mexicali for prolonged periods.

In response to the bottleneck, Mexican authorities made minimal efforts to maintain order, and in some cases even helped the U.S. authorities with metering the asylum applicants. However, civil-society organizations in Tijuana and the border region took on most of the responsibility, providing and managing 30 shelters and churches to house migrants. Many Mexicans protested that the government was doing more for the Haitian migrants than it does for Mexican deportees from the United States.

Coming on the heels of the experience with the Haitians, there is mounting evidence of protests by some Mexicans against new arrivals of Central Americans.

In executing this set of policies, the administration is trying through all means possible to stop asylum processing at the border. However, whether such actions will truly deter migrants from coming remains to be seen. The forces of deterrence, no matter how blunt, may not prove powerful enough to deter those whose motivation truly is to flee violence, repression, and instability in a dangerous Central American neighborhood.

- November 9 presidential proclamation on new asylum rules at the southern border

- Interim final rule on asylum at the southern border

- Order granting temporary restraining order in East Bay Sanctuary Covenant et al v. Donald J. Trump et al

- Amended complaint by plaintiffs in Al Otro Lado et al v. Kirstjen M. Nielsen et al

- Sessions ruling in Matter of A-B-, limiting asylum claims on grounds of domestic or gang violence

- Justice Department memo requiring asylum case completion within 180 days

- Justice Department memo establishing an expedited docket for migrant family cases

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection release on border-hardening efforts

National Policy Beat in Brief

Federal Appellate Court Rules Against Administration Attempt to End DACA. The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on November 8 upheld a lower-court order blocking the Trump administration from terminating the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Three days before the appellate ruling, the administration petitioned the Supreme Court to intervene—marking the second time it sought to push the high court to take the case ahead of the Ninth Circuit’s final ruling.

The administration has been enjoined by federal judges in New York, California, and Washington, DC from moving forward with its intent, announced in September 2017, to end DACA. As a result of the injunctions, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is required to continue adjudicating and granting applications from current recipients or those who had previously been enrolled in the program. DACA, created by President Obama in 2012, grants recipients work authorization and temporary protection from deportation. There are currently nearly 700,000 DACA recipients, and it is expected that congressional Democrats, who will retake control of the House in January, will press to resolve their uncertain status.

- New York Times article on the Ninth Circuit’s upholding of the DACA injunction

- Ninth Circuit opinion in Regents of the University of California v. DHS

- Politico article on the Justice Department’s filing to the Supreme Court

Hearing Concludes on Inclusion of Citizenship Question in 2020 Census. On November 27 a hearing in New York was completed on the Trump administration’s decision to add a question on citizenship status to the 2020 decennial census, for the first time since the 1950 census. The case, which awaits a judge’s ruling on the legality of the administration’s effort, was brought by 18 states, 15 cities, and a handful of civil-rights groups that charge inclusion of the question would adversely affect immigrants’ participation in the census. Cities and states are concerned about population undercount in their jurisdictions, costing their communities political representation and federal aid. Critics charge the move represents a raw political effort by the Republican administration to reduce participation in the census by Hispanics and other minorities.

The Justice Department had sought to delay the trial’s start. While the case was allowed to move forward, the Supreme Court initially blocked the deposition of Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, who made the decision to include the question. On November 16, the Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments concerning whether Ross, who has offered conflicting statements about the genesis of the decision and his consultations within and beyond the Commerce Department, can be deposed.

- Washington Post article on the citizenship lawsuit trial

- Bloomberg article on the Supreme Court’s decision to hear arguments on the Ross deposition

- MPI Policy Beat on the census citizenship question

Attorney General Jeff Sessions Resigns. On November 7, at the request of President Trump, Attorney General Jeff Sessions tendered his resignation. Despite demonstrating remarkable success in moving the administration’s immigration agenda forward, Sessions had long been faulted by the President for recusing himself from overseeing the Russia investigation undertaken by special counsel Robert Mueller. In less than two years as Attorney General, the former Alabama Republican senator was exceedingly effective at enacting wide-reaching and hardline changes to the U.S. immigration system.

- BuzzFeed News article on the resignation

- MPI Policy Beat on Sessions’ legacy as Attorney General and remarkable expansion of the use of the Attorney General’s referral power in immigration cases

New Foreign Student Enrollment Dropped in 2017. The number of international students coming to study at U.S. colleges and universities slowed for the second year in a row in 2017. While the United States remains the top global destination for international students, the number enrolling for the first time for the 2017-18 school year dropped to 173,121, nearly 7 percent less than the previous year. While college leaders have blamed the recent slide on rising anti-immigrant rhetoric by President Trump and hardened immigration policies, a variety of factors likely have contributed, including competition from universities in other countries and the rising cost of U.S. higher education.

- Politico article on the international student enrollment drop

- 2018 Open Doors Report on International Educational Exchange

USCIS Extends Enforcement Policy to Applicants for Humanitarian Benefits. On November 8, USCIS announced it will extend its recent policy on issuing notices to appear (NTA), which trigger removal proceedings, to unsuccessful applicants for certain humanitarian benefits. Under the original policy, announced on June 28, USCIS instructed immigration officers to automatically issue an NTA upon denial of an immigration benefit if the applicant has no lawful basis to stay in the United States. Initially, USCIS exempted applicants for humanitarian and employment-based benefits. The November announcement extends the NTA policy to applicants for T visas, which are reserved for victims of human trafficking; U visas, for victims of crime; and Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, for abandoned or abused children. Immigrant-rights advocates have expressed concern the policy will prevent such victims from coming forward to law enforcement agencies.

- USCIS press release on the NTA policy change

Departments of Homeland Security and Labor to Modernize the Recruitment Process for Temporary Foreign Workers. The Departments of Homeland Security and Labor on November 9 published proposed regulations that will update the application process for H-2A agricultural workers and H-2B nonagricultural workers (the latter filling temporary or seasonal needs in sectors such as tourism, hospitality, or landscaping). These visa programs allow employers to sponsor foreign workers if they can establish their inability to recruit U.S. employees.

Currently, before sponsoring foreign workers for these visas, employers must advertise for the jobs in print newspapers, giving U.S. workers the opportunity to apply. The proposed rule would allow employers to instead post job openings online, thus modernizing the application process and making it much faster and more affordable for employers.

- Federal Register notice of proposed H-2A change

- Federal Register notice of proposed H-2B change

Complying with Court Order, USCIS Extends Temporary Protected Status Protections for Sudanese and Nicaraguans. USCIS announced it will extend the Temporary Protected Status (TPS) protections for nationals of Sudan and Nicaragua until April 2019. The extension complies with an October 3 preliminary injunction issued by a federal judge in California that prohibits the federal government from terminating TPS for nationals of El Salvador, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Sudan while an underlying lawsuit moves forward. The government has not acted with respect to TPS for nationals of El Salvador or Haiti, since their benefits are not set to expire until later next year.

TPS protects foreign nationals already in the United States whose countries of origin are suffering from armed conflict, environmental disaster, or other unusual and temporary circumstances. The Trump administration has terminated TPS for every country where it believes the initial-designation conditions no longer apply, regardless whether new conditions make the country unsafe or would prevent the government from integrating returnees.

- CNN article on the TPS extension

- Federal Register notice complying with the court order on TPS

State and Local Policy Beat in Brief

New York Appeals Court Finds State Law Does Not Allow Cooperation with ICE Detainers. A state appellate court in New York ruled that state and local law enforcement agencies do not have authority to arrest and detain noncitizens upon request of federal immigration enforcement authorities. The ruling upended a policy implemented by a Suffolk County sheriff who agreed to detain immigrants for up to 48 hours after the completion of their criminal case if they were subject to a detainer from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). The court found the policy was illegal under New York law.

In the last several years, a number of state courts nationally have upheld legal challenges to local law enforcement compliance with directives from federal immigration enforcement officials.

- Newsday article on the court case

- Court opinion in Francis v. DeMarco

Michigan City Declines Justice Department Grant Due to Immigration Conditions. The city of Kalamazoo, Michigan declined a $92,000 Justice Department grant because of a requirement that the city comply with federal immigration enforcement. Outraged over the separation of families along the U.S.-Mexico border last summer, the City Commission had passed a resolution prohibiting city resources from being used to assist federal agencies in separating foreign-born children from their families or detain individuals based on their immigration status. Concerned that the grant conditions conflicted with this resolution, the city decided to forgo the grant.

The Trump administration has added a new requirement to the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant program that recipient jurisdictions must comply with federal immigration enforcement. A number of legal challenges have been brought across the country challenging the requirements.

- Kalamazoo Gazette article on the decision