You are here

Unaccompanied Minors Crisis Has Receded from Headlines But Major Issues Remain

U.S. Customs and Border Protection processes children arriving in South Texas (Photo: U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

July and August have witnessed a sharp decline in migration of unaccompanied children (UACs) and families from Central America. The wave of these migrants, which rose suddenly in May and early June, precipitated a crisis straining government agencies and service providers, and sparking intense national media attention and strong political reaction in Washington. The Central American flows have returned, at least for now, to their precrisis level, reducing the white-hot political and media focus. Underlying questions and challenges remain, however, concerning the fate of tens of thousands of newly arrived children and families now residing in the United States pending immigration court hearings, and the effectiveness of government policies in response.

While the child migration crisis may have abated, its effect on public opinion could prove long-lasting, with recent polls showing that public concern over illegal immigration is rising, trust in the Obama administration’s handling of immigration has fallen, and support for legalization for the unauthorized population has weakened. Congress declined to provide new funding requested by the Obama administration to address the crisis, despite an opportunity to do so in a $1 trillion stop-gap spending bill approved by both chambers and signed into law on September 19. Senate Republicans fell one vote short of amending the spending bill to include language that would prohibit President Obama from extending relief from deportation to more of the nation’s estimated 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants.

Central American Flows Take a Downward Turn

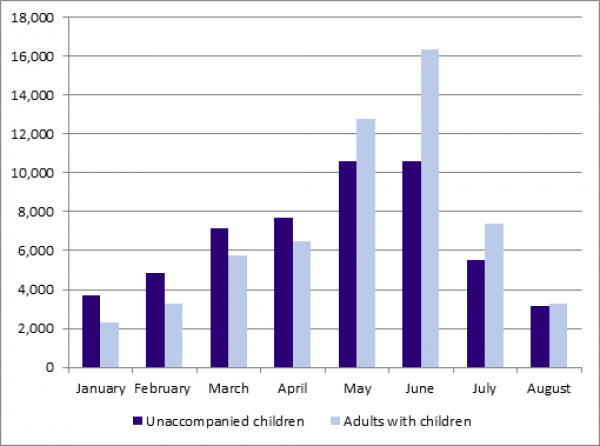

The number of unaccompanied minors taken into custody by the Border Patrol at the U.S.-Mexico border declined to just over 3,100 in August, after reaching a peak of 10,622 in June and declining to 5,501 in July. Apprehensions of family units (typically at least one parent traveling with one or more minor children) have followed a similar trajectory, cresting at more than 16,329 in June and falling to 3,295 by August. September apprehensions are expected to decline further.

As of August 31, for the fiscal year that began October 1, 2013, Border Patrol agents had apprehended 66,127 unaccompanied minors and 66,142 family units, the vast majority from Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala; most arrived in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas. Compared to the same 11-month period last year, family unit arrivals have surged by 412 percent, UAC arrivals by 88 percent.

|

Figure 1. Apprehensions of Unaccompanied Minors and Family Units at the U.S.-Mexico Border, 2014 Year to Date

|

|

Source: Department of Homeland Security, “Statement by Secretary Johnson About the Situation Along the Southwest Border,” (press release, September 8, 2014), www.dhs.gov/news/2014/09/08/statement-secretary-johnson-about-situation-along-southwest-border. |

The recent dramatic decline has been attributed to several factors: newly announced and implemented changes to detention and immigration court practices, focused public information campaigns by the Obama administration discouraging migration, a recent crackdown on illegal immigration in Mexico, and a seasonal tendency for Border Patrol apprehensions to decrease in late summer. What remains unclear is whether the decline is temporary, and some observers wonder whether another spike in arrivals is in store. “It would be premature at best to declare victory, to say the problem is behind us, because we don’t know,” Homeland Security Deputy Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said during a recent news conference. U.S. Customs and Border Protection Commissioner R. Gil Kerlikowske, speaking at a recent Migration Policy Institute event, said that "we should be very prepared" for another influx, but "it may not be anywhere near the levels that we saw."

In partnership with and under pressure from the United States, Mexico has intensified enforcement of its own immigration laws. Immigration checkpoints have been established along migrant routes, immigration raids have occurred in traditional staging areas, and authorities are now taking steps to prevent migrants from boarding freight trains—known colloquially as “La Bestia,” (“the beast”)—that run north through Mexico and to the U.S. border. An unprecedented 30,000 Central Americans have been deported from Mexico, including 20,000 children in the first seven months of this year, according to Mexico’s interior minister. According to other Mexican officials, 13,000 children and 64,000 adults who were apprehended at Mexico’s southern border have been deported.

Resettlement Challenges

What began as a national-level response to the child migration crisis in the United States has now shifted, as responsibility for resettlement and integration into local schools and the community rests in part with states and localities. As of August 31, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) (which takes custody of unaccompanied children after they are apprehended by the Border Patrol and reunites them with family members in the United States) had released more than 43,000 unaccompanied children to sponsors—mostly family members—across the United States. Many communities have struggled with integrating the newcomers; public school districts in particular are coping with the unexpected burden of new enrollments.

Providing services to the recently arrived child migrants carries additional expenses for local governments. Many of the young immigrants have limited English proficiency and possess varying levels of education, requiring alternative teaching methods and technologies. Some face emotional challenges associated with adjusting to a new culture, and becoming accustomed to living with family members from whom they may have lived apart for extended periods. Others are struggling to recover from trauma or violence they may have experienced in their home countries or on their journey north. Providing services to meet these needs has strained the budgets of some localities, generating resentment against the resettlement of the children.

Other communities have welcomed the opportunity to help the new arrivals. In the state of New York, which has received more than 4,700 unaccompanied children, the New York City Mayor’s Office has announced that it will begin stationing city agency representatives in immigration court to connect children to legal services as well as educational, health, and social services. In California, where more than 4,600 unaccompanied children had been resettled as of the end of August, Gov. Jerry Brown has proposed providing $3 million for legal services for unaccompanied children in removal proceedings. San Francisco already has allocated $2.1 million to the same cause.

Policy Responses

The challenge of resettling and integrating unaccompanied children while they await deportation hearings follows a series of policy changes and initiatives undertaken by the Obama administration designed to process the cases more quickly in court, provide legal counsel, improve care and services for children and families, deter future migration flows, and partner with the governments of Central America and Mexico. These changes are in various phases of implementation.

Fast-Track Hearings

In perhaps the most significant policy response to date, the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), which administers the immigration courts system, in late July began to implement fast-track hearings for unaccompanied children and families. Under the new policy, the courts are instructed to schedule an individual’s initial hearing within 21 days of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) initiating removal proceedings. As such, immigration courts across the country have been directed to place the new arrivals ahead of other cases on the docket. This sped-up process is in effect in several states, including Arizona, California, Florida, Maryland, New York, and Texas.

This process has come under intense criticism from immigration attorneys and advocates, who have voiced due-process concerns, arguing that accelerated hearings do not allow children adequate time to find a lawyer or build a strong case, especially as the child migrant influx has swamped legal service providers. Others maintain that the practice will further clog the court system by generating appeals and delaying non-UAC cases.

The fast-track hearing process has faced its own challenges: many children have been scheduled to appear in court in states other than where they have resettled with a family member, with only a few days notice. In these instances, immigration judges have typically transferred the cases to the appropriate immigration court. Reports suggest that in most accelerated cases, immigration judges have adjourned cases until the children have counsel present. The result is that the fast-track process has so far not achieved its intended goal of rapid deportations.

Access to Counsel

Senior administration officials have emphasized the importance of legal counsel for unaccompanied children in their immigration proceedings. Legal representation is a key factor that determines the outcomes in juvenile immigration cases. According to recent data released by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), juveniles who have legal representation in immigration proceedings are permitted to remain in the United States at least temporarily in nearly 50 percent of cases, while nine in ten juveniles without lawyers are ordered deported. In the wake of the child migration crisis, nonprofit legal service providers, law firms, and law schools—sometimes in collaboration with state and local governments—have mobilized to represent minors appearing alone in court. Despite these efforts, there is considerable unmet need for legal representation. The Obama administration has created a $2 million program that will pair 100 lawyers and paralegals with community-based organizations to provide representation and legal services to unaccompanied minors. It will not, however, go into effect until December.

At the same time, the administration has resisted calls to provide legal counsel at government expense to all unaccompanied minors. Under current immigration law and procedure, there is no requirement for government-paid legal representation in any immigration proceedings. In July, immigrant-rights groups filed a federal lawsuit in Seattle arguing that the federal government’s failure to provide legal representation to children in immigration court denies them a fair hearing and violates their constitutional right to due process. In opposing the suit, the administration argued that if the court ruled that unaccompanied minors are guaranteed a constitutional right to counsel, the government would be unable to remove any child under the age of 18 from the United States, in effect creating a magnet for future waves of child migration.

Increased Shelters, Detention Facilities, and Removals

Confronting the rapid flow of arrivals in late spring required expanding shelters and detention facilities appropriate for children. By early June, HHS had opened three temporary shelters at military bases in California, Oklahoma, and Texas—serving a total of 7,700 unaccompanied children. HHS has since closed all three shelters.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) also began detaining family units, sending a message that adults traveling with children would be detained upon arrival and swiftly returned to their home countries. In July, DHS opened a temporary family detention center in Artesia, New Mexico, which houses 400 residents, and in August began holding families at an ICE civil detention center in Karnes City, Texas.

Both facilities continue to operate. The Artesia facility has come under sharp criticism, with lawyers complaining about conditions there and claiming that the site’s remote location and visitation practices limit access to their clients. In August, several immigrant-rights groups filed a lawsuit against the Obama administration, alleging that efforts to quickly deport families from Artesia have resulted in egregious violations of due process. DHS has stated that the government has responded to reports of mistreatment at the Artesia facility and will continue do so “aggressively.” The Los Angeles Times has reported that as of August 21, nearly 300 adults with children have been deported from the Artesia and Karnes facilities.

Broader Implications

Though the issue of unaccompanied child migrants has receded from the headlines, it continues to have major political ramifications. In early September, President Obama acknowledged that fallout from the border crisis had caused him to delay a highly anticipated executive action to offer temporary relief from deportation to some of the country’s estimated 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants. “The truth of the matter is that the politics did shift mid-summer because of that problem," the president said.

Others point to mid-term election calculations, with many Senate Democrats facing tight reelection races. A new poll by GWU Battleground finds that more Americans trust Republicans to better handle immigration than Democrats, by 48 percent to 41 percent—a ratio that jumps to 61 percent in states with competitive Senate races.

Most importantly, the spike in Central American migration has reopened the national debate over whether the border is truly secure after nearly two decades of unprecedented enforcement spending, raised doubts about generous policies toward unauthorized immigrants, and hardened public opinion on the immigration issue in general. While the White House maintains that it has only temporarily postponed executive action and plans to move forward before the end of the year regardless of the situation on the border, the full impact of the child migration crisis will reveal itself in the months ahead.

National Policy Beat in Brief

Board of Immigration Appeals Issues Landmark Asylum Ruling. On August 26, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) issued a landmark decision, ruling that victims of domestic violence may be eligible for asylum. The ruling found that “married women in Guatemala who are unable to leave their relationship” can constitute a “particular social group” eligible to claim asylum or withholding of removal under U.S. law. To qualify for asylum, an individual must demonstrate past persecution or fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, and/or membership in a particular social group or political opinion. The lead respondent in the case is a Guatemalan woman who entered the United States without authorization in 2005 with three children, saying abuse by her husband prompted her to flee. In 2009, an immigration judge ruled that she was removable and denied her asylum application, on grounds that she did not meet the criteria of persecution for belonging to a particular social group. On appeal, BIA reversed that ruling. While the BIA decision applies only to women from Guatemala, it potentially creates a new legal opening to asylum for women from other countries who have experienced domestic violence.

- Board of Immigration Appeals decision in Matter of A-R-C-G et al.

State Department Modifies Fees, Increases Cost of Citizenship Renunciation. Following a fee review, the U.S. Department of State on September 12 began charging new application fees for certain immigrant and nonimmigrant visa categories. The fees for most categories of immigrant visas have changed, some going up, others down, while fees for nonimmigrant visas largely remain the same. Most notable is the dramatic increase in the price for renunciation of U.S. citizenship, from $450 to $2,350. The State Department contends that the process—which had previously been subsidized—is extremely costly, requiring U.S. consular officers overseas to spend substantial amounts of time processing and adjudicating cases. The State Department regularly conducts visa fee reviews and adjusts fees based on adjudication and processing costs.

Fees have been reduced for the following key visa categories:

- Employment-based immigrant visa applications, from $405 to $345

- Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and other I-360-based immigrant visa applications, from $220 to $205

- J-1 foreign residency requirement waiver applications, from $215 to $120.

- Treaty Investor and Trader E visa applications, from $270 to $205

Fees have been increased for the following key visa categories:

- Immediate relative and family preference immigrant visa applications, from $230 to $325

- Fiancée K visa applications, from $240 to $265

- Affidavit of support reviews, from $88 to $120

- Immigrant visa security surcharge, from $75 to $100

- State Department press release on the consular service fee changes

Thousands Could Lose Affordable Care Act Coverage Due to Immigration Status Concerns. At the end of September, an estimated 115,000 individuals will lose health-care coverage they registered for under the Affordable Care Act because the government has been unable to verify their citizenship or immigration status. In May, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) identified 966,000 individuals whose immigration status it could not confirm; the agency has since resolved 88 percent of these cases. In August, CMS sent letters to approximately 310,000 enrollees with outstanding questions about their citizenship or immigration documentation, giving them a September 5 deadline to submit proof of eligibility. CMS has stated that eligible individuals will have their coverage restored if they submit the necessary documentation. Naturalized citizens and certain lawfully present immigrants are eligible for coverage under the Affordable Care Act. Unauthorized immigrants are not eligible for benefits under the law.

- Politico article on Affordable Care Act coverage

- CMS update on consumers who have data-matching issues

Unauthorized Population Estimated at 11.3 Million. According to new estimates by the Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends Project, 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants resided in the United States as of March 2013. The report finds that the size of the unauthorized population has not changed since 2012 (11.2 million) and has remained essentially stable since 2009. Prior to the Great Recession, the unauthorized population had risen substantially each year since the 1990s, peaking at 12.2 million in 2007. The report found that as the size of the unauthorized population has leveled, the median length of time that unauthorized immigrants have lived in the United States has risen significantly, from less than eight years in 2003 to nearly 13 years in 2013. It also found that in 2012, 4 million unauthorized adults had at least one U.S.-born child in their household, compared to 2.1 million in 2000.

- Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends Project unauthorized immigrant population estimates

DHS Inspector General Releases Investigation into 2013 Detainee Releases. Between February 9 and March 1, 2013, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) released from detention 2,226 immigration detainees, including more than 600 with criminal convictions, according to a new report by the Department of Homeland Security Inspector General (IG). The release occurred in anticipation of the March 2013 government sequester. The IG report found that while ICE knowingly released immigrants with criminal convictions, including some whose detention is statutorily mandated, the agency did not release any individuals that it considered to be a threat to public safety. The report criticized ICE leadership for failing to inform DHS and other Obama administration officials of the planned releases, and called on ICE to better manage its detention budget and improve financial transparency.

- DHS Office of Inspector General report

State and Local Policy Beat in Brief

Boston Limits ICE Detainer Compliance. On August 21, the Boston City Council unanimously passed, and four days later Boston Mayor Marty Walsh signed, an ordinance titled the Boston Trust Act that limits the Boston Police Department’s compliance with federal immigration detainers. Under the new ordinance, police will no longer keep an individual in custody after his or her scheduled release on the basis of an ICE detainer, unless the federal agency has a criminal warrant for the individual or the person has been convicted of a serious crime. An immigration detainer, also called an immigration hold, is a federal request that a law enforcement agency hold an individual for up to 48 hours beyond the time the person would otherwise be released, allowing ICE to take him or her into custody for immigration violations. The Boston ordinance refers to several federal court rulings in recent months that have held that honoring civil immigration detainer requests based on less than probable cause constitutes violation of the Fourth Amendment, exposing local law enforcement agencies to liability.

- Read the Boston Trust Act

California Study Examines Role of Immigrants. Unauthorized workers comprise 10 percent of the California workforce and contribute $130 billion annually to state gross domestic product (GDP), according to a new study by the California Immigrant Policy Center and the University of Southern California. The study examines the demographics, labor force participation, economic contributions, entrepreneurship, and voting patterns among California immigrants. It found that the unauthorized make up 38 percent of agriculture workers and 14 percent of construction workers statewide. It also found that more than half of California’s unauthorized immigrants do not have health insurance, and that nearly three-quarters reside in households with at least one U.S. citizen. According to the report, California is home to 10.2 million immigrants, including 2.6 million (26 percent) who lack legal status.

- California Immigrant Policy Center report