You are here

United Kingdom’s Decades-Long Immigration Shift Interrupted by Brexit and the Pandemic

Refugees prepare to be resettled in the United Kingdom. (Photo: IOM/Abby Dwommoh)

In the 21st century, immigration to the United Kingdom had been larger and more diverse than at any other point in its history, at least until the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in 2020. In the nine-year period beginning in March 2011, an average of 336,000 more non-UK nationals moved to the country each year than departed. This represented a notable departure from previous decades. While the United Kingdom has received immigrants for centuries, it had traditionally been a net exporter of people. Only since 1994 has it consistently been a country of net immigration.

As arrivals grew, so did public sentiment against immigration. Yet for the most part, the government’s substantial reshaping of migration policy in recent decades has had little impact on either the scale of migration or public anxiety. Continued public opposition to migration was a critical driver of the 2016 Brexit vote that led to the country’s exit from the European Union.

A key consequence of this vote was implemented at the start of 2021, when UK and European leaders introduced major parts of a new migration system halting free movement to and from the United Kingdom and imposing a new visa regime. Much movement since 2020 has been prevented by the pandemic, however, so it has been difficult to assess the changes brought by this new regime.

After Brexit and as coronavirus mobility restrictions have eased, the United Kingdom finds itself at an inflection point. Its decades-long transition from prioritizing migrants from the former colonial empire to European workers and students has been interrupted. Yet fundamental economic dynamics are likely to reassert themselves once the public-health crisis subsides, and the United Kingdom will likely remain a country of net immigration going forward. The new immigration regime is likely to lead to changes in the flows of people and processing of goods to the United Kingdom, especially from elsewhere in Europe. At the same time, there has been a decrease in the salience of immigration in public debate since its high point in 2016, and a steady increase in positive attitudes toward immigration. So as the United Kingdom enters this new era for migration, it is doing so with a changed political dynamic, as well.

This article examines the policies and trends that have shaped migration to and from the United Kingdom since World War II, with a particular focus on events since the turn of the millennium.

Recent Immigration Patterns

The number of new immigrants and size of the UK foreign-born population has grown in recent years. From March 2019 to March 2020 (at the time of writing, the most recent period for which there were data), the United Kingdom received 708,000 migrants. Accounting for non-UK citizens who left the country, immigration increased the country’s population by 347,000 over this period.

A large majority of foreign-born UK residents live in England—90 percent in 2020—with 6 percent in Scotland, 2 percent in Wales, and 1 percent in Northern Ireland. In 2020, almost half were in the regions of London (35 percent, or 3.2 million people) or the Southeast (13 percent, or 1.2 million).

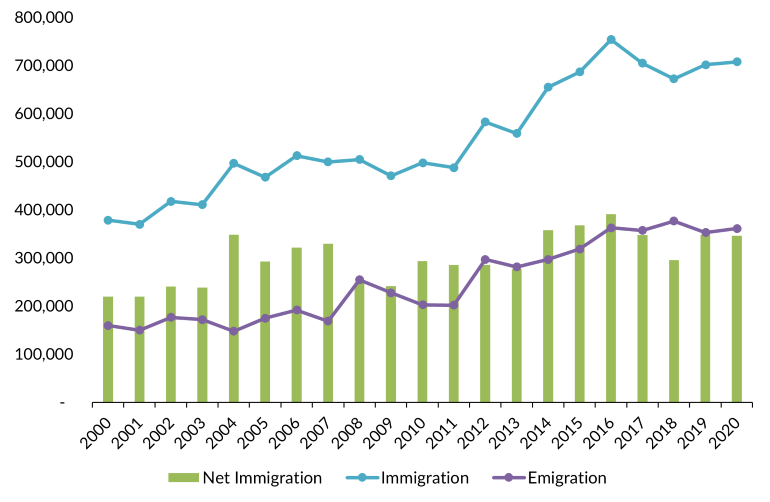

These figures suggest an overall growth of the UK population by slightly more than 3 million people in the nine-year period from March 2011 to March 2020, and by an estimated 6.3 million from January 2000 to March 2020 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Immigration, Emigration, and Net Migration to the United Kingdom, 2000-20

Notes: UK citizens are excluded. Data for years 2000 through 2011 are for calendar years, while data for years 2012 through 2020 are for financial years that run from March to March.

Sources: Data for the period from 2000 to 2011 are from Office for National Statistics, “Long-term International Migration, Table 2.00,” released November 26, 2020, available online; data for the year ending March 2012 to the year ending March 2020 are from Office for National Statistics, “Estimating Long-term International Migration Using RAPID,” released April 16, 2021, available online.

UK Immigrant Population

As of 2020 there were 9.2 million foreign-born UK residents, accounting for 14 percent of the overall UK population. At the same time, about 6 million residents were non-UK citizens (accounting for 9 percent of the overall population), which is a tripling since the early 1980s. Many foreign-born residents have become naturalized UK citizens.

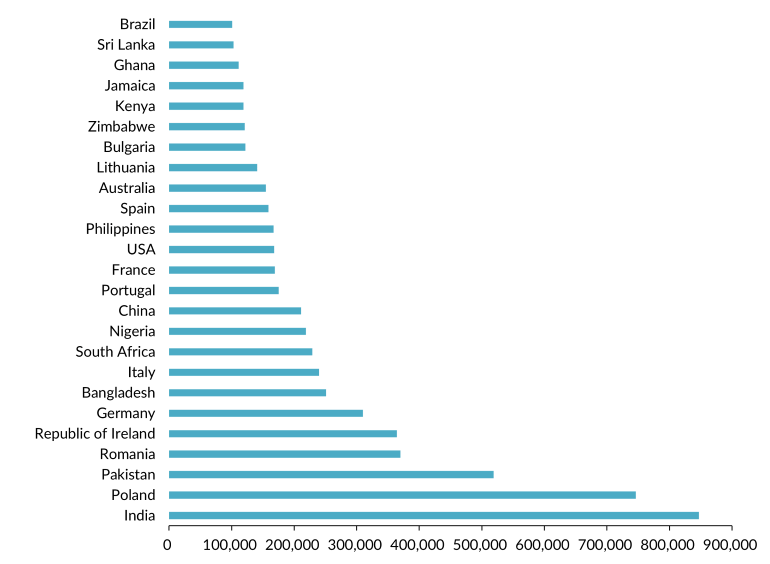

The five largest foreign-born populations were from India (approximately 847,000), Poland (746,000), Pakistan (519,000), Romania (370,000), and the Republic of Ireland (364,000).

Figure 2. Top Immigrant Populations in the United Kingdom by Country of Birth, 2020

Note: Population estimates are based on a sample survey with a margin of error that is not shown in the chart.

Source: Office for National Statistics, “Population of the UK by Country of Birth and Nationality,” released January 14, 2021, available online.

One characteristic of today’s migrant population is its increasingly diverse origins. In addition to employment- and family-related immigration from Europe and former colonies, humanitarian migration has contributed to this trend. For example, from 2011 to 2020, nearly 70,000 grants of protection (including to both asylees and resettled refugees) were to nationals of Syria (31,000), Iran (16,000), Eritrea (12,000), and Sudan (11,000).

A second characteristic of the UK immigrant population is its short stay. Data measurement issues prohibit a comprehensive judgment, but there is significant relatively short-term migration, although certain nationalities such as Syrians and other non-EU nationals tend to stay longer. For example, more than one-third of non-EU nationals have been in the United Kingdom for fewer than ten years; among EU nationals, the share of recent arrivals is likely to be higher. Of all non-EU migrants who arrived in 2009, just over one-fifth had acquired permanent residence ten years later. Migrants who arrive on family visas are more likely to stay permanently.

A third characteristic is the concentration of the foreign born in particular sectors of the economy. In 2019, 18 percent of all employed UK workers were born abroad, twice as large as the share in 2004. Workers born in India, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and older EU Member States known as the EU-14 are more likely than UK-born workers to be in high-skilled occupations, while those born in newer EU Member States are more likely to be in low-skilled occupations. Migrants are over-represented in several sectors, including hospitality (where they made up 30 percent of all workers in 2019); transport and storage (28 percent); information, communication, and information technology (24 percent); and health and social work (20 percent).

Finally, a small share of immigrants lack legal status. The Pew Research Center estimated there were between 800,000 and 1.2 million irregular immigrants residing in the United Kingdom in 2017. The Greater London Authority put this number at 674,000 in April 2017, although this excludes the UK-born children of irregular migrants (who under UK law are not granted citizenship); if these children are included the figure is 809,000. As with all estimates of irregular populations, these are highly uncertain and have critical limitations. But assuming the number is around 800,000, irregular migrants would make up around 9 percent of the total foreign-born population.

Historical Background and Development of Immigration Law and Policy

Large-scale emigration has dominated the history of movement from the United Kingdom. The British diaspora has historically been one of the world’s largest, and emigration remains significant. However, over the last 40 years, the United Kingdom has become predominantly a country of immigration.

Two major themes dominated the development of the immigration regime. First, as the United Kingdom deepened its ties with continental Europe mostly through what is now the European Union, Europeans increasingly enjoyed free movement and exemption from UK immigration control. This was the case until 11pm GMT on 31 December 2020, when these provisions ended as part of the implementation of Brexit (importantly, however, citizens of the United Kingdom and Ireland can continue to move freely to and reside in each other’s countries, due to the Common Travel Area between them).

The second theme, in contrast and conflict with the first, is the breakup of the British Empire and its consequences. For nationals of former colonies such as India and Jamaica, access to the United Kingdom has been progressively eroded as the idea of British citizenship changed from someone who was an equal member of the empire and subject of the queen to someone who was resident of or had direct ties to people in the four nations of the United Kingdom.

These trends did not happen immediately after World War II. Until the 1960s, immigration policy remained embedded in the structures and systems of the British Commonwealth, with Commonwealth citizens guaranteed the right to enter the United Kingdom. But as the empire fell apart, the United Kingdom’s ties with its former colonies frayed and were replaced by closer linkages with Europe—at least until 2016.

The Post-War Policy Model: Limitation and Integration

The 1948 British Nationality Act was the last piece of immigration legislation that aimed to assert Britain's role as leader of the Commonwealth. It affirmed the rights of Commonwealth citizens (including those of newly independent countries such as India) to move freely to the United Kingdom. After it, a new migration policy emerged based on two pillars: limitation and integration.

Limitation followed the immigration of workers from Commonwealth countries in the 1950s and early 1960s. The three laws that make up this pillar were enacted in 1962, 1968, and 1971, and together had the goal of zero net immigration.

The 1971 Immigration Act, with a few minor exceptions, repealed all previous legislation on immigration. It provides the structure of current UK migration law, giving the Home Secretary significant rulemaking powers on entry and exit. The core of the legislation was strong control procedures, including new legal distinctions between the rights of the UK born or UK citizens and people from former British colonies—notably the Caribbean, India, and Pakistan—who became subject to immigration controls.

The second pillar, integration, was inspired by the U.S. civil-rights movement. The approach mainly took the form of antidiscrimination laws: in a limited form in the 1965 Race Relations Act, in an expanded form in the 1968 Race Relations Act, and more comprehensively in the 1976 Race Relations Act.

The Conservative Era: 1979-97

Policy continued on similar lines during the 18 years of Conservative leadership from 1979 to 1997, albeit with a stronger emphasis on limitation and restriction, and with a sharper distinction on who was legally British. In particular, the British Nationality Act of 1981 ended centuries of common-law tradition by removing the automatic right to citizenship for anyone born on British soil.

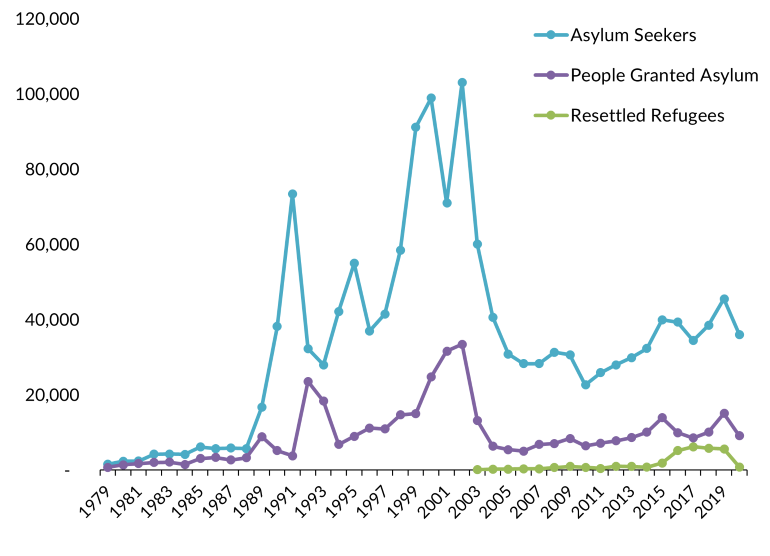

The target of policy changed from the late 1980s onwards, when asylum seekers became the government’s main concern. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the breakup of the Soviet Union, and early-1990s conflicts in the former Yugoslavia led to increased humanitarian flows to the United Kingdom and other European countries (see Figure 3). Policymakers, unused to seeing large numbers of asylum seekers arrive at their island doorstep, began to legislate change.

Figure 3. Number of Asylum Seekers, Positive Initial Decisions, and Refugees Resettled in the United Kingdom, 1979-2020

Notes: “People granted asylum” includes grants of humanitarian protection, discretionary leave, leave under family or private life rules, unaccompanied asylum-seeking child (UASC) leave, leave outside the rules, Calais leave, and exceptional leave to remain. Grants are an initial decision; the number of people granted some form of asylum-related leave are higher if appeals are taken into account. Resettlement data are for refugees resettled under the Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (VPRS), Vulnerable Children’s Resettlement Scheme (VCRS), Gateway Protection Programme, and Mandate Scheme. Data for resesettled refugees from 2003 to 2009 are from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and do not include small numbers of refugees resettled outside the UNHCR resettlement scheme. The United Kingdom has resettled refugees since 1995, but pre-2003 statistics are not available.

Sources: Authors' analysis of Home Office Immigration Statistics, “Asylum and Resettlement - Applications, Initial decisions, and Resettlement,” published May 27, 2021, available online; Home Office Immigration Statistics, “Asylum Tables – Asy_D01 and Asy_D02,” published May 27, 2021, available online; and UNHCR UK, “Resettlement Data,” accessed August 3, 2021, available online.

Two major acts of Parliament encapsulated the changes on asylum. The 1993 Asylum and Immigration Appeals Act was restrictive, creating fast-track procedures for asylum applications considered to be without foundation, allowing detention of asylum seekers while their claim was decided, and reducing asylum seekers' benefit entitlements. The 1996 Asylum and Immigration Act continued in the same vein with new measures designed to reduce asylum claims, such as further welfare restrictions.

Four parliamentary acts related to Hong Kong were also enacted in this period, in 1985, 1990, 1996, and 1997. The first concerned the transfer of British sovereignty over Hong Kong to China, and the latter three were reactions to changes in Hong Kong and actions by the Chinese government, including offering additional types of status to people in the territory.

The Labour Era: 1997-2010

When the Labour Party came to power in 1997, immigration policy shifted course. Emphasis was placed on “selective openness” to immigration. Limiting and restricting immigration ceased to be a pillar of UK policy, and focus was on accommodation for workers and students, particularly those from the European Union. Meanwhile, a tough security approach towards other types of migrants accelerated after 9/11 and has included greater efforts to combat irregular immigration and reduce asylum seeking through various measures, especially new visa controls. This change in approach was accepted across the political divide.

While moving on from limitation, the Labour government however expanded on the second post-war pillar of integration. It reinforced antidiscrimination measures under a banner of equality and developed policies around community cohesion, which at the time meant bringing together segregated communities and fostering shared values and belonging.

The Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act of 2002 and other policy changes around this time were turning points in the shift to accommodate foreign-born workers and students. The government expanded avenues for economic immigration and for the first time introduced visas for highly skilled workers without a job offer. In addition, policies to encourage international students and new labor market programs presaged the development of a points-based system.

Above all, when eight Eastern European countries joined the European Union in May 2004, the United Kingdom allowed their nationals to enter and work without restriction (nearly all other EU states took years to admit these workers). This decision changed the patterns of immigration, most notably leading to large increases in immigrants from Poland and other Eastern European countries to work in low-wage jobs. The strong UK economy proved attractive to many Eastern Europeans; together with restrictions elsewhere in Europe, high unemployment at home, favorable exchange rates, and pent-up demand, migration soared. Between May 2004 and May 2009, about 1.3 million people from the 2004 EU members arrived in the United Kingdom. Polish nationals jumped from being the United Kingdom’s 20th largest foreign-national group at the end of 2003 to number one by 2008.

In response to public and media disquiet over such high levels of immigration, the government introduced a new approach in 2008 which governed immigration from outside the European free-movement zone: a five-tier Points-Based System (PBS) incorporating revised and consolidated versions of existing labor migration schemes.

Asylum and Control

While it opened to economic immigrants and students, the government tried to control asylum and irregular migration, amid high numbers of arrivals and rising public anxiety. The United Kingdom received between 28,000 and 55,000 asylum applicants per year in the early and mid-1990s, but this number rose rapidly in the late 1990s and peaked in 2002 with more than 103,000 applicants. The challenge was epitomized by the “Sangatte crisis,” during which prospective asylum seekers massed at the French port of Calais, across the English Channel from Dover, and regularly attempted to reach the United Kingdom without authorization, usually as stowaways in trucks.

As numbers rose, so did public pressure to curb asylum. The government passed successive laws aimed at reducing the number of asylum applications, speeding up processing, and more effectively removing failed asylum seekers. Visa regimes got tougher; financial penalties were imposed on air and truck carriers; and pre-boarding immigration controls were enacted at various European ports. These measures together amounted to an expansion of the UK border.

Less effective in curtailing asylum claims—but nonetheless intensely consequential for individual migrants—have been policies targeting asylum seekers within the United Kingdom. The government restricted access to benefits and the labor market, increased surveillance and detention, and relocated many outside London and Southeast England in a process known as “dispersal.” The number of people in immigration detention increased by more than two-thirds in the 2000s.

Concerns about asylum seekers and irregular migrants are closely linked and sometimes conflated in UK politics and media, in part because many asylum seekers arrive without authorization and are referred to as spontaneous arrivals. In addition to external measures such as tougher visa regimes, the government took four main steps to control irregular migration. First, in 2008 the government began issuing Biometric Residence Permits with fingerprint and other data for all non-EU foreign residents intending to stay longer than six months. Second, it imposed more severe sanctions on companies employing irregular migrants. Third, it imposed measures on public services, such as restricting immigrants’ access to nonemergency health care. Finally, in a deviation from the otherwise restrictive measures, it granted legal status to between 60,000 to 100,000 people from 2000 to 2009, most of whom had been in the country for 13 years or more (seven years for members of immigrant families) or had long-outstanding asylum claims.

Multiculturalism, Inclusion, and Belonging

The United Kingdom’s longstanding multiculturalist model of immigrant integration was tested on the heels of three 2001 events: riots involving minority communities in several northern towns, the Sangatte crisis, and the September 11 terrorist attacks. The July 7, 2005 attacks on London's transit system led to further concerns about social segregation between White and minority ethnic and religious groups, especially Muslims. In parallel, support in some areas rose for far-right political parties including the British National Party (BNP), which saw two high-profile members elected to the European Parliament in June 2009.

During Labour’s period in power, four strands of policy emerged to counteract these trends. Its refugee integration strategy—introduced in 2000, strengthened in 2005, and ended in 2010 when Labour lost power—made refugees eligible for orientation services and financial assistance. Its community cohesion efforts aimed to bring segregated communities together through a variety of local-level initiatives such as projects encouraging education and religious links within diverse student bodies. The government created additional tests and steps for acquiring citizenship. And finally, it reinforced and extended the country’s antidiscrimination framework, including by enshrining the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) in UK law and making it illegal to stir up hatred on racial or religious grounds.

While concerns over segregation and radicalization led to an expansion of the equality agenda, the government’s increased attention to Muslim populations explicitly and increasingly came under the security-centric heading of preventing extremism. At times, this came ahead of fostering mutual tolerance.

Conservatives Back in Power: 2010-Present

Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron’s coalition government assumed office in 2010 with plans to lower immigration while maintaining its economic value. Then-Home Secretary and later Prime Minister Theresa May introduced a blunt immigration target of 100,000 net arrivals per year, but the government failed to achieve that goal despite enacting many policy and regulatory changes to do so. Net immigration never fell to fewer than 172,000 since 2010 (including UK citizens), and reached a peak of more than 391,000 in the fiscal year ending March 2016.

Partly with the intention of driving down numbers, the government enacted salary thresholds for sponsors wishing to reunite with family in the United Kingdom and for those coming for work. It has also targeted the irregular immigrant population through a policy known as the “hostile environment,” formed by the Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016. In short, the policy is a series of measures aiming to make life so difficult for irregular migrants that they leave the country of their own volition, while also deterring people from becoming irregular migrants in the first place. It has involved increased enforcement and demands on public and private services such as landlords, banks, and employers to refuse to provide services to individuals who cannot demonstrate their legal status.

The hostile environment policy led in part to the 2018 Windrush scandal, in which members of the Windrush generation—predominantly British citizens from the Caribbean—who lacked paperwork to prove their citizenship were treated as irregular migrants, often forced into poverty, and in some cases detained and deported to countries they had not set foot in for decades. In 2020 the government agreed to implement the recommendations of the official Windrush Lessons Learned Review, which exposed structural issues and discrimination by the Home Office to members of the Windrush generation and the negative impact of hostile environment policies.

Throughout this period, pressure grew to restrict the free movement of EU citizens despite its status as a fundamental right core to the European Union. Immigration frequently topped the polls of the country’s most important political issues. After five years of failing to reduce numbers of arrivals, Cameron’s Conservative Party won an outright majority in 2015. He no longer had a strong polling lead on the issue (trust in politicians’ abilities to deal with immigration was generally very low), and immediately agreed to hold a referendum on EU membership, which took place in 2016.

The net immigration target and hostile environment were the two main immigration legacies of the government prior to the Brexit vote. Other key policies were an end of most immigration detention for children—a manifesto commitment from the Liberal Democrats as part of the price of its 2010-15 coalition—and the response to the Syrian refugee crisis, which included an expanded refugee resettlement scheme, a new sponsorship system, and £400 million of additional funding from 2015 to 2019.

Brexit

Europeans’ freedom of movement featured prominently in Brexit debates, and opposition helped drive 52 percent of Britons to vote to leave the European Union in 2016. The referendum led to multiple years of political wrangling, ultimately concluding with the Withdrawal Agreement, passage of which was achieved after the Conservatives’ landslide 2019 election victory.

The withdrawal did two big things. Firstly, it ended free movement from the European Union. In its place, the government implemented a new version of the Points-Based System, broadly an employer-led work permit system, for all immigrants coming to work long term, including from the European Union. As part of that, it aimed to meet a new goal of ending the immigration of low-skilled workers, with the exception for seasonal agricultural workers who can enter under a new scheme (previously, the United Kingdom had relied on low-skilled migrants from Europe able to travel freely).

The second major change was the creation of the EU Settlement Scheme granting permanent residence to EU citizens already living in the country. Resident EU citizens had until the end of June 2021 to apply for the scheme. More than 6 million people applied (including eligible EU citizens no longer in the United Kingdom)—far more than had been expected—with the vast majority being approved status.

Brexit will have long-term consequences beyond the ending of free movement. Among other changes, leaving the European Union has accelerated the implementation of technology in UK immigration management (such as the automated decision-making in the EU Settlement Scheme) and changes to administrative law. The United Kingdom is also no longer part of the Common European Asylum System, so is no longer eligible for schemes involving the transfer of asylum seekers between EU Member States or access to the fingerprint database of people who have illegally entered or made an asylum application in other EU countries.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic spread around the globe just as the United Kingdom was finalizing its EU departure. The impact of the pandemic on migration patterns has been immense globally, and the United Kingdom was no exception. The country essentially experienced a short but complete pause in international migration and short-term travel, followed by a reduction of movement by between one- and two-fifths.

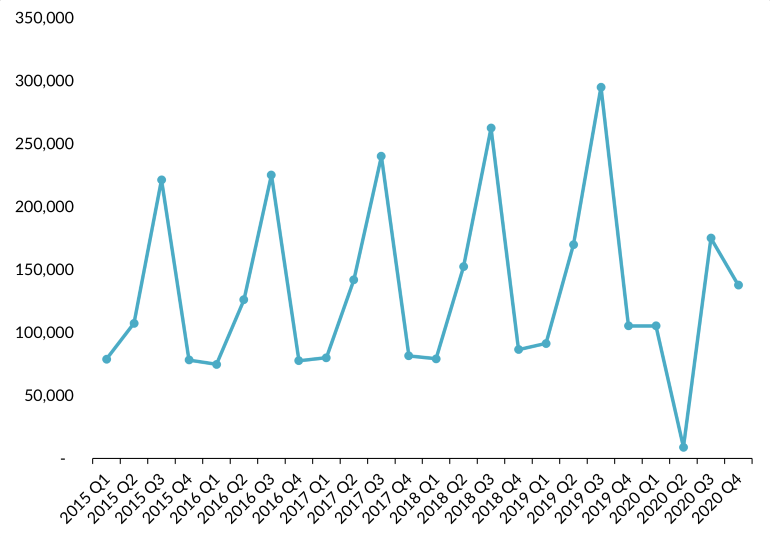

Overall, the United Kingdom issued 35 percent fewer visas to non-EU nationals in 2020 than in 2019 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Number of UK Visas Issued to non-EU Nationals, 2015-20

Note: Regular spikes in all visas reflect the seasonal nature of student visas, most of which are issued in the third quarter (July to September), before the start of the university year in September.

Source: Authors' analysis of Home Office Immigration Statistics, “Entry Clearance Visas - Summary Tables,” published May 27, 2021, available online.

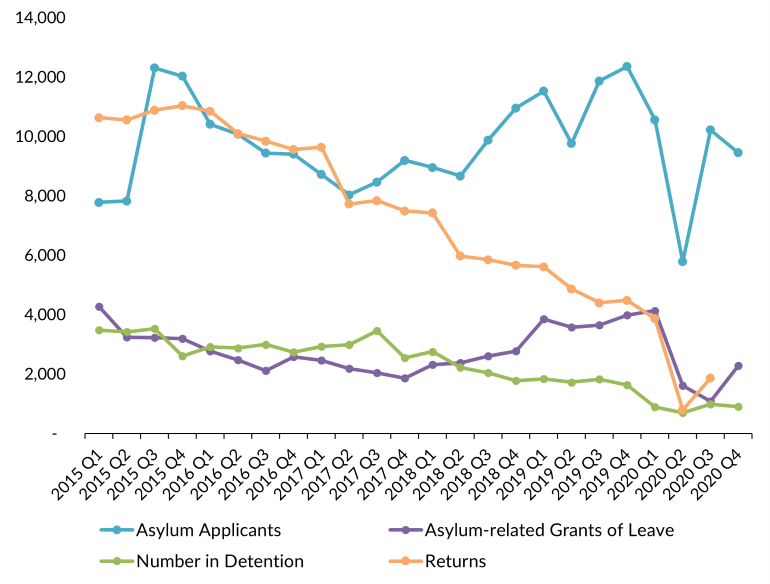

The dropoffs for asylum, detention, and returns were even starker. While the number of asylum applications quickly rebounded, there were 40 percent fewer asylum grants in 2020 than in 2019, and almost half as many migrants in detention at the end of 2020 as at the end of 2019 (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Number of UK Asylum Applications, Asylum Grants, Immigration Detainees, and Returns, 2015-20

Notes: Asylum figures include main applicants and their dependent family members. People granted asylum include those granted asylum or another form of leave at initial decision, excluding appeals. Counts for people held in immigration detention are taken on the last day of the quarter and include those detained under immigration powers in prisons. Returns figures will rise in subsequent releases as data checks are made on people leaving the United Kingdom.

Source: Authors' analysis of Home Office Immigration Statistics, “Immigration Statistics Data Tables, Year Ending March 2021,” published May 27, 2021, available online.

Still, analysts expect net immigration to continue to remain high; the Office for National Statistics has predicted net immigration of 2.19 million people for the decade up to 2028, although this forecast may be reduced in light of the pandemic’s impact.

Similarly, the pandemic led to reactive changes to policy, including visa extensions, encouraging of remote interviews and hearings on asylum claims, and free health screenings for migrants without status. These were largely temporary measures, although many of the technological developments will likely remain in place after the pandemic’s end.

Recent Developments: 2019-2021

The December 2019 election of Prime Minister Boris Johnson and a Conservative government with an 80-seat majority provided a mandate to complete Brexit and reshape the UK immigration system, which has been fulfilled. In many ways, the government’s approach on immigration going forward remains designed to exert control, reduce arrivals, and maintain economic value.

However, 2019 was also the bookend of the experiment with a blunt immigration target. Johnson ended the policy supported by his predecessor, along with the promise of both certain prescribed liberal routes (such as for high-skilled scientists) and more rigid approaches to spontaneously arriving asylum seekers and others not coming through authorized routes.

One liberal route created in 2021 was to Hong Kong, to counteract new security laws and crackdowns by China. Driven by colonial history, economic interest, and posturing towards China as much as by liberalized immigration instincts, the UK government in January opened a new pathway to citizenship for British National Overseas (BNO) citizens in Hong Kong and their close family members. An estimated 5.4 million people are eligible, nearly three-quarters of Hong Kong’s population. More than 34,000 people applied in the first three months of the year, and the government has estimated that between 123,000 and 153,000 people from Hong Kong will migrate to the United Kingdom in the first year.

Since spring 2021, political and media focus has mostly been on migrants in small boats crossing the Channel from France in order to seek asylum. In 2020, there were around 8,500 people detected crossing the English Channel in small boats. In 2021 up to August, over 10,000 such people were estimated to have been detected.

More recently, the government has sought to rein in access to humanitarian protection. In April it published its New Plan for Immigration which eyes reforms to the asylum and refugee system, promising substantial change to admissibility and adjudication of claims. In July, it proposed the Nationality and Borders Bill to strengthen criminal penalties for entering the country illegally and allow asylum seekers to be detained in a third country while their claim is processed. Meanwhile, nongovernmental organizations have raised concerns about asylum seekers' rates of poverty, access to employment, quality housing, health care, and education, and have campaigned vigorously against their detention—particularly of children and families—and to increase their access to justice.

The government’s efforts to deter spontaneous asylum seekers and support a very limited refugee resettlement scheme proved untenable in August, amid the Taliban’s rapid seizure of power in Afghanistan. While details were continuing to emerge at the time of writing, the United Kingdom has announced a new “bespoke” resettlement scheme to accept a total of 20,000 Afghans needing protection, including 5,000 in the first year.

Looking Ahead

It is unclear how the new, post-Brexit immigration system will function in practice, especially in terms of low-paid workers. Immigrants are essential to a number of economic sectors, and there will be significant pressure on the government to consider new routes to accommodate market demand.

There is also likely to be change on the political scene following the seismic impacts of both the pandemic and Brexit. Starting around 2015 and accelerating after the 2016 referendum, the public debate notably shifted, with immigration being seen as less important. In the December 2019 election, it was rated as only the ninth most important issue facing the country, according to an Ipsos MORI poll. There are differing explanations for this development, but one factor is clearly that people concerned about immigration believe the government has exerted or will exert greater control over the issue, leading to a reduction in their concerns.

Policymakers will continue to face a complex set of challenges, including new plans for humanitarian arrivals and to meet labor market needs. Some of these challenges are likely to become particularly acute as new systems of trade and entry become embedded in the months and years after COVID-19 and Brexit.

This article draws in part on material from the 2009 Country Profile of the United Kingdom by Will Somerville, Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah, and Maria Latorre, "United Kingdom: A Reluctant Country of Immigration," which is available here.

Sources

Ashcroft, Michael. 2016. How the United Kingdom Voted on Thursday... and Why. Lord Ashcroft Polls, June 24, 2016. Available online.

Clery, Elizabeth, John Curtice, and Roger Harding. 2017. British Social Attitudes 34. London: NatCen Social Research. Available online.

Connor, Phillip and Jeffrey S. Passel. 2019. Europe’s Unauthorized Immigrant Population Peaks in 2016, Then Levels Off. Washington: Pew Research Center. Available online.

Fernández-Reino, Mariña and Cinzia Rienzo. 2021. Migrants in the UK Labour Market: An Overview. Briefing, Migration Observatory, Oxford, England, January 2021. Available online.

Fernández-Reino, Mariña and Madeleine Sumption. 2020. Citizenship and Naturalisation for Migrants in the UK. Briefing, Migration Observatory, Oxford, England, March 2021. Available online.

Gordon, Ian, Kathleen Scanlon, Tony Travers, and Christine Whitehead. 2009. Economic Impact on the London and UK Economy of an Earned Regularisation of Irregular Migrants in the UK. London: Greater London Authority (GLA). Available online.

GOV.UK. 2021. Bespoke Resettlement Route for Afghan Refugees Announced. News release, August 18, 2021. Available online.

Home Office Immigration Statistics. 2020. Immigration Statistics Data Tables, Year Ending June 2020. Published August 27, 2020. Available online.

---. 2021. Asylum and Resettlement - Applications, Initial decisions, and Resettlement. Published May 21, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Asylum Tables – Asy_D01 and Asy_D02. Published May 27, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Entry Clearance Visas - Summary Tables. Published May 27, 2021. Available online.

Ipsos MORI. 2017. Shifting Ground: 8 Key Findings from a Longitudinal Study on Attitudes Towards Immigration and Brexit. London: Ipsos MORI. Available online.

---. 2020. Ipsos MORI Issues Index: 2019 in Review. London: Ipsos MORI. Available online.

Jolly, Andy, Siân Thomas, and James Stanye. 2020. London’s Children and Young People Who Are Not British Citizens: A Profile. London: GLA. Available online.

Office for National Statistics. 2019. National Population Projections: 2018- Baseline. Released on October 21, 2019. Available online.

---. 2020. Long-term International Migration 2.00, Citizenship, UK. Released November 26, 2020. Available online.

---. 2021. Estimating Long-term International Migration Using RAPID. Released April 16, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Population of the UK by Country of Birth and Nationality. Released January 14, 2021. Available online.

Papademetriou, Demetrios G. and Will Somerville. 2008. Regularisation in the United Kingdom. London: CentreForum.

UN High Commissioner for Refgees (UNHCR) UK. N.d. Resettlement Data. Accessed August 3, 2021. Available online.

Walsh, Peter William. 2020. Irregular Migration in the UK. Briefing, Migration Observatory, Oxford, England, September 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. Migrant Settlement in the UK. Briefing, Migration Observatory, Oxford, England, August 2020. Available online.

Walsh, Peter William and Madeleine Sumption. 2020. Recent Estimates of the UK’s Irregular Migrant Population. Briefing, Migration Observatory, Oxford, England, September 2020. Available online.

Woodbridge, Jo. 2005. Sizing the Unauthorised (Illegal) Migrant Population in the United Kingdom in 2001. London: Home Office. Available online.