You are here

The U.S. Stands Alone in Explicitly Basing Coronavirus-Linked Immigration Restrictions on Economic Grounds

President Trump signs an immigration proclamation. (Photo: Joyce Boghosian/White House)

All countries across the globe have imposed travel or immigration restrictions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Adding to a suite of earlier restrictions, the United States in April became the first—and so far only—country to explicitly justify mobility limitations not on grounds of health risk, but to protect the jobs and economic wellbeing of U.S. workers.

On April 22, President Donald Trump issued a proclamation to suspend the granting of visas to certain categories of permanent immigrants who “present a risk to the U.S. labor market during the economic recovery following the COVID-19 outbreak.” The proclamation further called on government agencies to use the same criteria to consider imposing similar restrictions on temporary foreign workers, giving rise to widespread speculation that more announcements are imminent.

The real impact of the proclamation remains uncertain. But there is little doubt that the narrative and intent of the proclamation bear strong resemblance to an immigration agenda that the president promoted both before and after his election. Indeed, on a leaked recording of a call for White House supporters to outline the legal immigration restrictions, Stephen Miller, the president’s key immigration advisor, said: “The first and most important thing is to turn off the faucet of new immigrant labor. Mission accomplished.’’

With unemployment having surged from 3.5 percent in February to 14.7 percent in April, and with government officials acknowledging the rate could reach the 25 percent level last recorded during the Great Depression, the restrictions hold some messaging power for the administration, particularly with the president’s base.

Yet if the administration’s mission is to reduce immigration, the proclamation may be having limited results—at least initially. With the pandemic disrupting government operations, the State Department in March had already suspended in-person consular interviews and visa processing for the vast majority of intending immigrants. And current U.S. law allows for unused green-card numbers from the categories banned under the proclamation to be allotted to other intending immigrants who are not subject to the ban, or to roll them over for distribution the following year. Thus, overall green-card issuance is unlikely to drop significantly, though the ban will prevent some businesses from being able to sponsor workers from abroad, and many U.S. nationals and permanent residents from reuniting with relatives.

But the rumored ban on nonimmigrants could have a significant impact, especially if applied to nonimmigrant workers already in the United States. The businesses that depend on such workers would face immediate shortfalls, and already corporate interests have lobbied the White House against implementation of such a measure. The ban could upend workers’ lives, stranding them in unlawful status as they would likely be unable to return to their home countries amid a worldwide travel shutdown that is only now showing the faintest signs of ending. And, if continued for an extended period of time, the ban would make U.S. universities less competitive for highly sought after international students, and would undermine U.S. businesses’ ability to attract global talent, including workers the administration itself has deemed critical to the nation’s public health and safety.

A Perceived Economic Threat

The president’s April 22 proclamation reducing legal immigration was announced when COVID-19 infections stood at 828,441 cases, with transmission rising rapidly—as of May 27, the number had more than doubled to nearly 1.7 million cases. Instead of pegging the new restrictions to the health-care crisis, the proclamation justified the legal immigration halt by pointing to the growing economic freefall and its implications for the labor market. It was the first time in U.S. history that a labor market rationale was cited to suspend entry of immigrants otherwise qualified under immigration law. Under the proclamation, for at least 60 days immigration for permanent residents from abroad will be limited to spouses and minor children of U.S. citizens and immigrant investors who invest at least $900,000 in U.S. businesses.

The parents, adult children, and siblings of U.S. citizens; spouses and children of permanent residents; diversity lottery winners; and nearly all types of employment-based immigrants are barred under the proclamation. In fiscal year (FY) 2019, 315,000 immigrants entered the United States as permanent residents through the categories now suspended, in other words 26,000 individuals per month. Applicants for employment-based green cards are more likely to already be in the United States working on nonimmigrant temporary visas. Since the proclamation does not apply to such green-card applicants, it disproportionately disadvantages those seeking family reunification. The proclamation would reduce employment-based immigration by 15 percent, versus 35 percent for family-based immigration.

However, in practical terms, the proclamation—for now—changes little. Earlier coronavirus-related bars on travel to the United States from 31 countries (the 26 Schengen countries in Europe, Brazil, China, Iran, the Republic of Ireland, and the United Kingdom) remain in place. So do the administration’s original September 2017 travel ban and its February 2020 expansion, which continue to block immigration to varying degrees from 13 countries (Eritrea, Iran, Kyrgyzstan, Libya, Myanmar, Nigeria, North Korea, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tanzania, Venezuela, and Yemen). At the time of the April 22 proclamation, the administration had already suspended processing of nearly all visas at U.S. consulates for a month. And nonessential travel across the country’s land borders has been suspended.

Even if the proclamation is in effect after consular processing resumes, it is unlikely that the total number of green cards granted this year will decrease at the rate of 26,000 per month. Two factors explain this prediction.

First, the ban only applies to those in the suspended categories who are applicants outside of the United States, and not to those who apply within the country—the latter continue to remain eligible to obtain green cards. Indeed, there are about 826,000 potential immigrants in backlogs in the categories the proclamation covers, waiting inside the United States (including 628,000 employment-based applicants and 198,000 family-based applicants).

Whether or not these applicants can take advantage of the green-card numbers freed by the suspended categories will depend on the State Department, which is tasked to ensure that green-card issuance is maximized under the statutory limits. Thus, there may be adjustments of numbers within the same category.

The second factor is a provision of immigration law mandating that unused family green-card numbers be rolled over to employment-based applicants in the following year, and vice versa. In some categories this works better than others, but it would allow at least some of the unused green cards this year to be used in 2021.

Standing Apart in the Global Fight Against the Pandemic

Even though the United States thus far is the only country to explicitly justify mobility restrictions on economic grounds, by the end of April, all countries had placed some international travel curbs in response to COVID-19, according to the UN World Travel Organization. In just a few months, the world has experienced the largest and fastest decline in global human mobility in modern history.

Individual governments have framed these as either immigration or travel restrictions, or both; the policies vary greatly in scope—from minimal to complete shutdowns. For example, Peru, Namibia, and Ecuador closed their borders to all international arrivals, including their own citizens. As of April 20, 65 countries had totally or partially suspended international flights. This has been more common in Africa and the Middle East, where 45 percent and 54 percent of countries respectively had suspended flights.

As of April 20, 39 countries had banned the entry of individuals traveling from specific countries. For example, Turkey banned entry—even for transit—of all foreign nationals from more than 70 countries.

Other countries have excluded travelers on the basis of their immigration status—but these are largely focused on temporary visitors or workers. Many countries have suspended tourism—as of April 27, according to UN World Travel Organization, 72 percent of international “destinations” had completely closed their borders to international tourists. Singapore banned all “short-term visitors.” Norway closed its borders to all foreign nationals without residency permits. Similarly, Thailand banned the entry of all foreign nationals unless they are authorized to work in the country. And Australia canceled the visas of existing and returning temporary visa holders currently outside of the country and unable to return due to the country’s ban on entry for anyone other than Australian citizens and permanent residents; thus, even valid visa holders are unable to enter Australia.

If the Trump proclamation is in effect beyond the date upon which the State Department resumes visa processing, the United States may once again stand apart and become the only country to block certain permanent immigrants while continuing to allow most temporary travelers.

On the other end of the spectrum, some countries have extended benefits or relief to immigrants. In Portugal all foreign nationals with pending immigration applications, including asylum seekers, will be temporarily treated as permanent residents, allowing them to access health care and other benefits until at least July 1. (Portugal’s policy leaves out seasonal migrant workers and some unauthorized immigrants.) The United Kingdom is providing automatic extensions for many temporary workers, including doctors, nurses, and paramedics whose status will be automatically extended by a year. China automatically extended work and residency permits and provided welfare support to the migrant labor force impacted by the coronavirus. And Italy announced that it would give unauthorized agricultural and domestic workers temporary legal status and work authorization.

In the United States, many immigrants, especially the unauthorized, are explicitly excluded from federal coronavirus-related benefits—such as stimulus cash payments and supplementary unemployment benefits. At least four states (California, Michigan, New Jersey, and Washington) and eight localities (Austin, Boston, Chicago, Minneapolis, Seattle [with King County, Washington], St. Paul, and Washington, DC, along with Montgomery County, Maryland) had stepped in, at this writing, to partially fill the gap. California, for example, has created a disaster relief fund to provide residents with one-time stimulus payments if they were ineligible for federal payments because of their immigration status.

Anticipated Restrictions for Nonimmigrants

The president’s proclamation rationalized its focus on permanent immigrants as more of an economic threat to U.S. nationals. According to the text of the proclamation, nonimmigrants are less of an economic threat because, unlike lawful permanent residents, they are restricted to working in specific sectors and for specific employers. The proclamation curtailing legal immigration was greeted coolly by immigration restrictionists and others in the Trump base who viewed it as a modest measure; they are pressuring the administration to advance new restrictions, including for some nonimmigrants.

The president tasked the Departments of Labor and Homeland Security, in consultation with the State Department, to review nonimmigrant programs and recommend measures to ensure that U.S. workers receive priority in the labor market. According to media reports, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) sent these recommendations to the White House in mid-May.

While the administration’s plan has yet to be released, speculation has focused on three temporary work programs: Optional Practical Training (OPT), which allows foreign students to be employed for up to three years after graduating from U.S. colleges and universities; H-1B visas for certain skilled professionals, and H-2B visas for temporary nonagricultural labor. On May 7, U.S. Senators Tom Cotton (R-AR), Ted Cruz (R-TX), Charles Grassley (R-IA), and Josh Hawley (R-MO) wrote the president urging him to suspend the issuance of all new temporary worker visas for 60 days, and to suspend issuance of new H-2B and H-1B visas and the OPT program for one year or until national unemployment figures “return to normal levels.” However, in a sign the move is not universally accepted even in the president’s party, 51 Republicans in Congress—nine of them U.S. senators—wrote the president urging him not to impose restrictions on the H-2B program.

Each of these temporary programs has faced criticism in recent years and there is widespread agreement that employment-based immigration is due for a broad rethink, but a sudden suspension promises to inject even more instability into already uncertain times for businesses that rely on foreign workers. And if new restrictions apply to workers already in the United States, it will lead to loss of employment and potentially strand foreign workers in the United States, many of whom have deep roots in the country and have made important contributions to U.S. communities and the economy.

Optional Practical Training

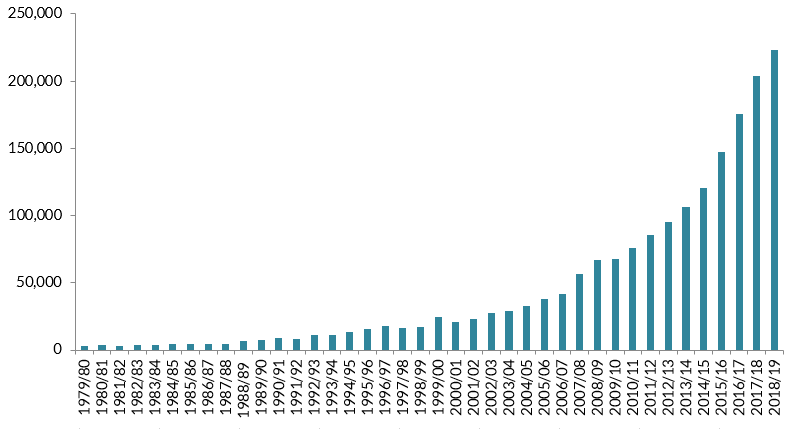

OPT allows foreign students studying at U.S. universities to be employed for up to 12 months before or after completing their studies. Students who have earned a degree in science, technology, engineering, or math (STEM) may apply for a 24-month extension (36 months total). Participation in the program has grown significantly in recent years; in the 2018-19 school year, there were 223,085 students on OPT.

Figure 1. OPT Participation, School Years 1979/80 – 2018/19

Source: Institute of International Education (IIE), “International Student and U.S. Higher Education Enrollment, 1948/49 - 2018/19,” accessed May 27, 2020, available online.

There has long been concern about the effect OPT may have on U.S. workers because there are almost no labor protections built into the program. Employers have no obligation to try to recruit U.S. workers before hiring a foreign national on OPT or pay a prevailing market rate—raising concerns that the program undermines U.S. workers.

The Trump administration has already tried to address these concerns, for example by requiring employers of students on OPT STEM extensions to attest that the students will not replace U.S. workers and will receive compensation commensurate with similarly situated U.S. workers.

Because the H-1B visa category for skilled professionals has been so oversubscribed in recent years, employers heavily depend on OPT as a bridge from a student visa to the H-1B visa. In the STEM fields, since OPT is extended to three years, if employers begin applying during the student’s final year of study, they get four opportunities to try their luck in the H-1B lottery.

While there is little data available on the employment patterns of OPT recipients, STEM fields undoubtedly dominate the program. During the 2018-19 academic year, 40 percent of international students were studying engineering, math, or computer sciences.

OPT is also an important draw for international students. Considering the recent decline in the enrollment of international students as Canada and other countries increasingly compete for young talent and tuition dollars, suspending OPT would be a further blow to U.S. universities. Since its peak during the 2015-16 school year, new international student enrollment in U.S. colleges and universities has fallen each year: in the 2018-19 school year, new enrollment was 10 percent lower than in 2015-16.

The H-1B Program

In much the same way that OPT serves as a bridge between student and H-1B visas, H-1B visas serve as a bridge to permanent immigration status. Each year, more than one-third of new H-1B visas are granted to foreign nationals on student visas. And, according to FY 2014 data obtained by the Bipartisan Policy Center under the Freedom of Information Act, 60 percent of in-country applicants for employment-based green cards are adjusting H-1B holders and their dependents. While normally time spent on an H-1B visa is capped at six years, if an applicant has an active green-card application he or she may stay on the visa until a green card is available, a process that for some can take decades to materialize.

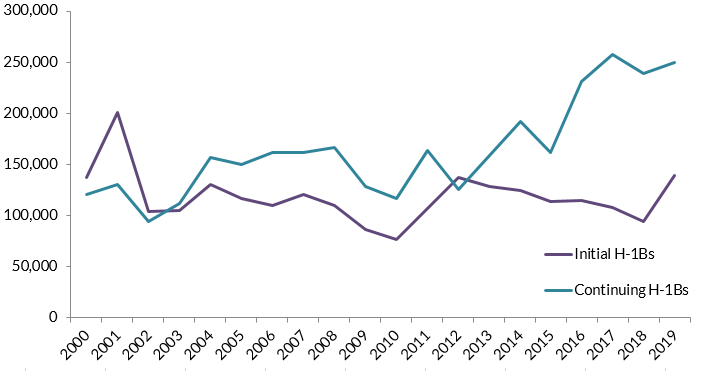

The H-1B visa is the main vehicle through which U.S. businesses can employ skilled foreign workers. In FY 2019, 388,403 H-1B visa petitions were approved. The number of H-1B applications approved for applicants already on H-1B visas who are extending their stay in the country has grown significantly in recent years; between 2010 and 2019 the number of these “continuing” H-1B approvals doubled, from 116,363 to 249,276. This rise is at least in part because of the growing pool of foreign nationals working on H-1B visas for years as they wait for backlogged green cards.

Figure 2. Approved H-1B Petitions for Initial and Continuing Applicants, FY 2000-2019

Source: Department of Homeland Security (DHS), “Characteristics of Specialty Occupation Workers (H-1B),” various years, accessed May 26, 2020, available online.

This visa category has long been dominated by technology industries, with 66 percent of approved H-1B petitions in FY 2019 going to workers in computer-related occupations.

The program has faced substantial criticism for decades, with some reports documenting that U.S. workers are being replaced by H-1B visa holders. Trump took up U.S. workers’ cause on the campaign trail in 2016, even featuring at his rallies U.S. workers who had to train their H-1B replacements.

The Trump administration has tried to address this issue by increasing scrutiny for H-1B petitions, especially targeting IT consulting companies. As a result, approval rates for these companies have drastically decreased. For example, one of the biggest traditional H-1B employers, Cognizant Technology Solutions, saw its approval rate for initial H-1B petitions fall from 95 percent in FY 2016 to 39 percent in FY 2019.

Despite this criticism of the program, employers’ demand has never been higher. Shortly before the COVID-19-related lockdown, U.S. employers filed 275,000 applications—the largest ever—for the 85,000 H-1B visas allotted annually through a lottery. The surge was also driven by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) debuting an online registration process for the H-1B lottery. However, considering the dramatically different economic landscape since early spring, it is unclear how many of the beneficiaries will still have a position come their October 1 start dates.

The H-2B Program

Employers can use the H-2B visa to bring in foreign workers to perform temporary nonagricultural jobs. In recent years, top H-2B occupations have included landscaping, groundskeeping, forestry, amusement park work, and housekeeping. Before employers can be granted H-2B visas they must obtain approval from the U.S. Department of Labor, certifying that there are no U.S. workers who are qualified and available to fill the temporary position. But there is controversy about the sufficiency of this labor market test.

H-2B visas are limited to 66,000 per year. However, each year in the past five years Congress has allowed USCIS to accept workers beyond this cap, with as many as 80,000 additional visas granted in a single year. These increases are the result of intense lobbying from employers that are dependent on temporary workers, especially in the hospitality, construction, seafood, and landscaping industries.

Already this year the administration approved and then reversed, amid protest, an expansion of the H-2B visa cap. Initially in March, DHS announced it would increase the cap by 35,000 visas, preserving 25,000 visas for foreign nationals who had previously entered on H-2B visas and another 10,000 visas for new workers from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The carveout for the Central American countries resulted from their acquiescence to U.S. demands to sign asylum cooperation agreements intended to limit the arrival of asylum seekers and other migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border. However, DHS on April 2 withdrew the expansion, clarifying via Twitter that no additional H-2B visas would be released until further notice.

Without this expansion, as of February 18, all H-2B visas for the fiscal year had been allotted. However, many of the beneficiaries are likely still outside of the United States, expecting but perhaps unlikely to receive visas shortly before their actual start dates this year.

Recognizing the importance of H-2B visas, the State Department designated the visas as “mission critical” and announced U.S. embassies and consulates would continue to process them to the extent possible during the pandemic.

In addition, USCIS is allowing employers to hire H-2B workers who are already in the United States but whose term of employment is about to expire, if their employment relates to the nation’s food supply chain. According to USCIS, these workers “ensure continuity of functions critical to public health and safety, as well as economic and national security and resilience of the nation’s critical infrastructure.”

Thus, there is clear ambivalence—or discordance—in the administration’s policy on entry or employment of immigrants post-COVID. On the one hand, there is a nod to U.S. businesses that rely on foreign workers, and on the other there appears to be a political imperative, especially in an election year, to appease those concerned about immigration levels—a reality turbocharged for some by the skyrocketing unemployment rates.

Even in the tension between these two competing pulls, the administration has chosen to justify its new restrictions not on pandemic-related concerns, but on economic challenges. In the process, it may have guaranteed the longevity of this policy long past the health crisis.

- Presidential Proclamation “Suspending Entry of Immigrants Who Present Risk to the U.S. Labor Market During the Economic Recovery Following the COVID-19 Outbreak”

- Letter from Republican U.S. Senators Tom Cotton, Ted Cruz,, Charles Grassley, and Josh Hawley urging the suspension of visas for temporary workers

- Press release from the UN World Tourism Organization, “World Tourism Remains at Standstill as 100% of Countries Impose Restrictions on Travel”

- Report from the UN World Tourism Organization on COVID-19-related travel restrictions

- Report from USCIS, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers FY 2019

- Temporary final rule making changes to the H-2B nonagricultural worker program

- Coronavirus case tracker from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- MPI explainer on how the U.S. legal immigration system works

- Newsweek article on changing public attitudes toward immigration amid the pandemic

- Reuters article on immigrants left out of Portugal’s safety net