You are here

Rise of X: Governments Eye New Approaches for Trans and Nonbinary Travelers

U.S. passport with "X" marker. (Photo: iStock.com/golibtolibov)

In April 2022, the United States joined a growing list of countries that allow for a third gender option (“X”) in passports. This policy also allows transgender applicants to self-select their gender as “male” or “female” and removes the requirement to provide medical documentation if their gender does not match other identification documents. The change also effectively permits any U.S. citizen (not only those who are nonbinary, intersex, or gender-nonconforming) to opt out of sharing their gender by choosing an X.

When it comes to state recognition of sex/gender, there historically have been only two possibilities to choose from: male and female. Partially in response to the expansion of transgender rights, however, a global shift to embracing a third option (alternatively called “X,” “other,” “unspecified,” or “third gender”) has increasingly taken place over the past decade. Australia was the first country to adopt the X marker for transgender and intersex individuals on a wider scale in 2011, after a single instance of an X passport issuance in 2003. A number of other countries (Bangladesh, Canada, Denmark Iceland, India, Malta, Nepal, New Zealand, and Pakistan) followed suit by introducing third gender and nonbinary possibilities, of which the X marker in the sex/gender field has become the most common. Courts in Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands have also paved the way for a third option outside the male-female binary. (In Germany, this decision sought to address intersex individuals in specific.) Although it remains to be seen if this option will be extended to all trans and nonbinary individuals desiring an X, these judicial decisions will likely have reverberations throughout the European Union and internationally.

Even as more countries are adopting the X option, uptake for this gender marker remains relatively low, in part because some trans and nonbinary individuals are concerned about their safety while traveling with an unspecified marker. Given that most countries’ visa applications and many airline systems offer only binary options for identifying sex/gender, the X inevitably leads to incongruency between documents, which can provoke security responses. For many, this has inhibited possibilities for economic- and religious-based travel and migration. And border management systems and agencies have yet to evolve, with the X remaining unknown to many border control agents and passport screeners. Similarly, not all security technologies and computer systems have been updated to include a third gender option.

This article examines the introduction of the X marker, the impacts of gender markers on transgender and nonbinary travelers and migrants, and the evolving policy landscape ahead.

Box 1. Terminology

Cisgender: People whose gender identity aligns with their sex assigned at birth.

Gender: The social and cultural meanings often ascribed to sex-based differences.

Gender diverse: Subjectivities that diverge from normative or binary sex/gender identification, embodiment, and/or presentation. This term may include individuals who identify as transgender, gender-nonconforming, intersex, or nonbinary, as well as those who may have undergone a sex/gender transition or confirmation at some point in their lives but now identify along binary lines.

Intersex: The range of conditions and sex characteristics, including chromosomal patterns, gonads, or genitals, that do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies.

Nonbinary: Individuals who do not identify within the gender/sex binary of man/woman or male/female.

Sex: Refers to a range of physical, chromosomal, hormonal, and anatomical differences and generally maps to the categories of male, female, and intersex.

Trans: Umbrella term that includes all gender identities that transcend binary-gendered categories.

Transgender: People who identify with a gender other than that which was assigned to them at birth.

Impacts of Gender Markers on Transgender and Nonbinary Travelers and Migrants

The inclusion of sex/gender in passports greatly impacts transgender and nonbinary travelers and migrants when they cross international borders. Although it may seem a minor bureaucratic matter to those whose gender presentation aligns with their documentation, transgender and gender-diverse populations regularly experience harassment and disenfranchisement while traveling internationally, including being questioned or detained because of documentation that does not meet the expectations of border control authorities and security technologies. This treatment is often due to discrepancies between physical appearance (e.g., gender expression, dress, behavior) and the sex/gender marker included in identity documents. Due to the many administrative and medical hurdles in updating documentation, many trans people have inconsistencies across documents, which can be cause for being stopped due to alleged falsification of identity documents. Full body scans and pat-downs—a regular feature of international travel—can also result in humiliation or harassment.

Some trans and nonbinary people have developed strategies to prevent questioning or actively conceal their gender identity by traveling as a gender that matches their documents but not their true identities. Many transgender individuals also experience high levels of anxiety and stress before, during, and after traveling. These obstacles have been a reason for many to avoid international travel altogether out of threats to safety or fear of discrimination. In short, current border regimes frequently pose a challenge for those not conforming to gender norms.

Because many countries still require documentation of having undergone sex reassignment surgery or other forms of medical transition to update gender markers in passports, international travel and migration effectively remain impossible for many trans individuals. Such surgery is financially out of reach for many, while others simply do not want to undergo medical transition. According to a 2020 report from the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law, transgender people face unique obstacles obtaining identification documents that reflect their gender. While this study specifically focused on identity verification for voting purposes, its conclusions can be extrapolated to other identity documents, including passports. Holding a passport that does not accurately reflect one’s gender (including name and gender marker) can cause significant problems when traveling, migrating, or interacting with border security agents.

Trans and nonbinary refugees also encounter significant—sometimes insurmountable—obstacles when seeking humanitarian protection. While there is a significant body of literature on the issues faced by gay and lesbian asylum seekers, the barriers encountered by transgender and nonbinary asylum seekers are only beginning to be explored. Even though gender identity and gender expression are grounds for international protection (under the “particular social group” designation that is one of five categories recognized under the 1951 Refugee Convention; the others are persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, or political opinion), transgender and gender-diverse refugees encounter numerous impediments in being granted asylum, including invasive questioning in the credibility assessment process or characterization as medically or psychologically abnormal.

The Introduction of the X

The rise of third gender markers begins to address some of the serious obstacles that transgender and nonbinary people face in accessing accurate documentation that allows for international mobility. While the process of changing documentation is uneven across geopolitical contexts, the introduction of the X marker has generally been celebrated as rectifying outdated understandings of gender as binary and as a victory for nonbinary recognition. In countries that allow for a third gender marker in passports, there are significant differences in terms of requirements. Australia, for example, requires a statement from a medical practitioner attesting that the applicant is transgender and identifies as X, is intersex, or is of indeterminate sex. In New Zealand a statutory declaration of transgender, nonbinary, or intersex identity is required, while in the United States an X passport can be granted by self-identification. In Malta, the X option is available to all citizens regardless of gender identity. In fact, in what is seen as a best-practices model, Malta will issue individuals with an X passport a second passport with M or F for reasons of safety.

In countries that have long and rich precolonial traditions of third-gender categories and communities, such as India, Bangladesh, and Nepal, passports have been issued with other markers, including “O” (“other”). (This marker technically violates international passport guidelines, which do not allow for an O marker in the sex/gender field.) While the X is purely optional in most countries that allow for it and is often elected by those who identify outside the gender binary, in Nepal and Pakistan the marker is mandatory for all transgender people seeking to update their documents. That is, even binary trans people who identify as male or female are given an X marker. Such application and implementation of third gender markers could affect the most vulnerable travelers, i.e., those possessing non-Western passports with unspecified gender markers, and open them up to increased scrutiny at border checkpoints.

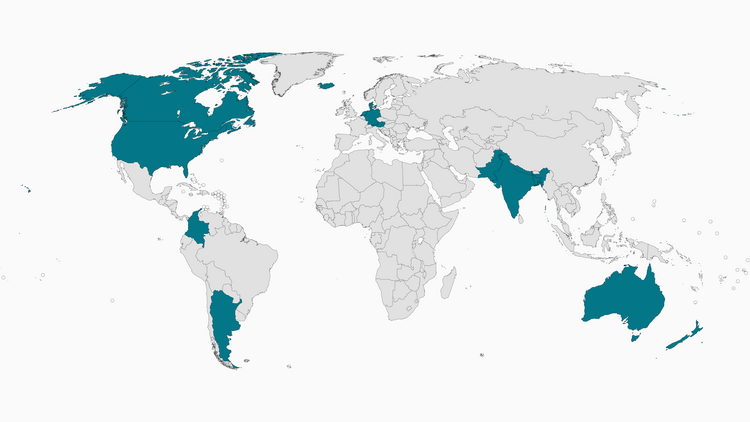

Figure 1. Countries Authorizing the Use of X or Other Third Marker on Passports, 2022

Notes: Malta is among the countries authorizing use of the third gender marker but is difficult to distinguish due to the map's size. In a number of other countries, Chile and the Netherlands for example, courts have handed down decisions allowing for nonbinary legal recognition for specific individuals or in specific cases. Belgium, South Africa, Taiwan, and Uruguay have recently instituted or are expected to imminently introduce third gender markers in national identity documents, potentially paving the way for X passports in the future.

Source: C.L. Quinan and Mina Hunt, “Non-Binary Gender Markers: Mobility, Migration, and Media Reception in Europe and Beyond,” European Journal of Women’s Studies 28 (4): 1-11.

While the origins of the X are disputable, one theory traces its existence to the postwar period in Europe. Prior to World War I, crossing borders was relatively simple for most individuals, and it was only with the war’s onset that nations in Europe and elsewhere began introducing passport requirements for reasons of security and control. There is some evidence that the X was borne out of that contemporary refugee situation and was made possible due to International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) guidelines put in place after World War II to handle the flood of refugees worldwide. ICAO had to issue large numbers of emergency passports, and for reasons of expediency, the X was purportedly used when aid workers could not tell from the paperwork if the person was male or female.

Passports standards are governed by ICAO Document 9303, which determines the guidelines with which passports must comply to be machine readable. These prescriptions include a field for sex/gender, with three options: M, F, and X. In 2012 New Zealand conducted a review of the requirement to display gender in passports and explored possibilities for removing the gender marker entirely. The resulting report found removal of the gender marker would raise national security concerns. It also concluded that the costs outweighed the benefits “given the adverse effects on the operations of border authorities and the potential inconvenience for passengers.” It did, however, acknowledge that there are benefits to eliminating the sex/gender field and left open the possibility of revisiting the issue once border control systems are less affected by removal of the field.

Effects of the Changing Landscape

While the focus of this article is limited to documentation necessary for movement between countries, it is important to acknowledge that changes to passport markers often are preceded by smaller-scale policies that may involve other accommodations for transgender and nonbinary identification. For example, simple changes to sex/gender markers in birth certificates, drivers’ licenses, ID cards, and the like at federal, state, or provincial levels have often triggered the acknowledgment of categories such as nonbinary, intersex, other, unspecified, or prefer not to say. While such legal and policy developments will not always translate into the inclusion of the X marker in passports and the facilitation of international mobility for trans and nonbinary individuals, this changing landscape likely points to an expansion of the third gender option in passports. Also, because the X marker in passports is allowed by international guidelines, it could, in theory, be adopted by any of the 193 ICAO Member States by administrative change.

There are many advantages to the X. Most importantly, the impact that state recognition has on the health and wellbeing of transgender and nonbinary individuals cannot be overstated. Some trans and nonbinary people with X passports have said that travel is easier (both logistically and emotionally) with their amended documentation. The X may also be a way of sidestepping the requirement for all individuals (including cisgender people) to share gender in travel documentation, especially given that the proliferation of post-9/11 identity verification has resulted in significant privacy concerns.

Challenges to Adoption of the X Marker

Even as there have been flashpoints over policies related to gender identity (for example, the denial of gender-affirming health care or the restriction of public bathrooms to one’s sex assigned at birth), there has been relatively little pushback to the adoption of the X marker.

Though the third gender marker has not touched off a wider societal debate, there may be unintended consequences and challenges to its broader use, not least the fact that existing bureaucratic structures, technologies, and computer systems exist in a binary world when it comes to sex and gender. Low uptake of the X marker at present and frequent incongruency between identity and travel documents can put travelers and migrants at risk. For example, several Pakistani transgender individuals with X passports who applied for a visa to perform the Hajj and Umrah in Saudi Arabia were denied because the visa only includes “male” and “female” options. This has dissuaded many Pakistani transgender people from updating their documents. Beyond the difficulties in securing a visa from countries that do not recognize a third gender marker for travel or migration, an X passport can also have impacts on migratory possibilities in countries that are hostile to transgender issues. Even in countries that do allow for the X, there may be administrative and bureaucratic challenges, as visa forms and paperwork are not always updated to include other markers outside male and female. Such small inconsistencies can trigger denial, rejection, and delay of visa processing.

While some airlines have added an undisclosed or unspecified gender option to their booking systems, many airlines only offer a binary option. Despite the U.S. government’s recognition of the X marker for passports, some major air carriers still require travelers to select between “male” and “female,” though changes are coming.

Similarly, even countries that offer the X in passports cannot guarantee that border control in other nations will allow entry, transit, or even legal protection. Transphobic laws and social attitudes can also filter down to border control. For this reason, some national advocacy groups have been lobbying for allowing for an option such as that offered by Malta whereby people with X passports can apply for a second passport with a binary gender marker to enter countries that do not recognize the X. Some governments also note whether other countries are favorable to the X marker or not. The Smart Traveller website from Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs, for example, indicates that Australians traveling with an X passport to the United Arab Emirates will be barred from entry. This is a significant concern for Australians with X passports traveling internationally given that Dubai is a major hub for international flights from Australia. More broadly, the Smart Traveller website acknowledges the challenges of international travel with an X marker, stating, “If you're travelling on a passport showing 'X' in the sex field you may encounter difficulties when crossing international borders.”

Meanwhile, despite some governments’ best intentions, other administrative issues have posed challenges for X passports. In Canada, the X option was introduced in 2017, but it took more than a year to update software and machines that formatted and printed passports. This meant that anyone updating or applying for a passport with an X marker during that period received a document with a binary gender marker on the bio page, with a sticker on the next page stating “the sex of the bearer should read as X, indicating that it is unspecified.” In essence, the X was made possible only in theory, illustrating the unforeseen challenges governments can face in quickly adopting a third gender marker without careful consideration of implementation and other effects.

In the post-9/11 era, international border crossing has been chiefly seen through a national security lens, and those with any documentation anomalies set off alarm bells and may be treated as suspicious or threatening. Given the fact that many—if not most—trans and nonbinary people have mismatches between gender presentation and the gender marker in their passports and/or may hold identity documents with varying gender markers, they are susceptible to being detained, interrogated, and humiliated at border checkpoints. This is even further exacerbated for those experiencing intersecting forms of oppression, including, but not limited to, racism, ableism, xenophobia, and Islamophobia.

Because most nonbinary people worldwide do not have access to the X marker, this also means that they are forced to lie when presented with only “male” or “female” gender options. While the X attempts to rectify discrimination, there remains significant need for careful assessment of the challenges and consequences that nonbinary, third gender, and alternative gender markers may pose for trans and gender-diverse travelers, migrants, and refugees.

The nonbinary third gender marker might begin to rectify the ways that border security structures disproportionately impact trans and gender-diverse individuals, but it is also important that a more careful review of instruments such as the X be conducted to ensure the safety and security of transgender and nonbinary travelers.

Sources

Allen, Samantha. 2019. Airlines, Including Delta, to Add New Gender Options for Non-Binary Passengers. The Daily Beast, February 15, 2019. Available online.

Australian Government, Smart Traveller. 2022. United Arab Emirates. Last updated April 11, 2022. Available online.

Avgeri, Mariza. 2021. Assessing Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Asylum Claims: Towards a Transgender Studies Framework for Particular Social Group and Persecution. Frontiers in Human Dynamics, Section Refugees and Conflict, May 24, 2021. Available online.

Blinken, Antony J. 2022. X Gender Marker Available on U.S. Passports Starting April 11. U.S. Department of State press statement, March 31, 2022. Available online.

Camminga, B. 2019. Transgender Refugees and the Imagined South Africa: Bodies Over Borders and Borders Over Bodies. N.p.: Palgrave Macmillan.

Chiam, Zhan, Sandra Duffy, Matilda González Gil, Lara Goodwin, and Nigel Timothy Mpemba Patel. 2020. Trans Legal Mapping Report 2019: Recognition Before the Law. Geneva: International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association (ILGA) World. Available online.

Davis, Dylan Amy. 2017. The Normativity of Recognition: Non-binary Gender Markers in Australian Law and Policy. Advances in Gender Research 24: 227-50.

European Commission. 2020. Legal Gender Recognition in the EU: The Journeys of Trans People Towards Full Equality. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online.

Holzer, Lena. 2018. Non-Binary Gender Registration Models in Europe. Report on Third Gender Marker or No Gender Marker Options. Brussels: ILGA-Europe. Available online.

---. 2020. Smashing the Binary? A New Era of Legal Gender Registration in the Yogyakarta Principles Plus 10. International Journal of Gender, Sexuality and Law 1 (1): 98-133. Available online.

International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). 2012. A Review of the Requirement to Display the Holder’s Gender on Travel Documents. ICAO information paper TAG/MRTD/21-IP/4, December 2012. Available online.

---. 2021. Machine Readable Travel Documents, 8th edition, Doc 9303. Available online.

Intersex Campaign for Equality. 2021. For Intersex Awareness Day: The History of the X Passport Marker. Intersex Campaign for Equality, October 26, 2021. Available online.

Kilpatrick, Sean. 2017. Canadians to Be Able to Use ‘X’ Option for Gender on Passports. The Globe and Mail, August 24, 2017. Available online.

Knight, Kyle. 2015. Nepal's Third Gender Passport Blazes Trails. Human Rights Watch, October 26, 2015. Available online.

Knight, Kyle G., Andrew R. Flores, and Sheila J. Nezhad. 2015. Surveying Nepal’s Third Gender: Development, Implementation, and Analysis. Transgender Studies Quarterly 2 (1): 101-22.

Ng, Bryan. 2022. Nonbinary Airline Passengers Ask: What’s Gender Got to Do with It? New York Times, June 22, 2022. Available online.

Office of the UN High Commissioner for Civil Rights (OHCHR). 1966. Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Available online.

O’Neill, Kathryn and Jody L Herman. 2020. The Potential Impact of Voter Identification Laws on Transgender Voters in the 2020 General Election. Los Angeles: UCLA School of Law Williams Institute. Available online.

Open Society Foundations (OSF). 2016. License to Be Yourself: Responding to National Security and Identity Fraud Arguments. OSF Legal Gender Recognition Issue Brief. Available online.

Quinan, C.L. and Nina Bresser. 2020. Gender at the Border: Global Responses to Gender-Diverse Subjectivities and Nonbinary Registration Practices. Global Perspectives 1 (1): 1-11.

Quinan, C.L. and Mina Hunt. 2021. Non-Binary Gender Markers: Mobility, Migration, and Media Reception in Europe and Beyond. European Journal of Women’s Studies 28 (4): 1-11.

Rogers, Kristen. 2021. How the Letter X Is Changing the Game for Travelers — and What That Could Mean for the US.” CNN, March 18, 2021. Available online.

Safronova, Valeriya. 2021. Passports May Soon Include a New Option for Gender Identity. New York Times, February 24, 2021. Available online.

Spade, Dean. 2015. Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of Law. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2012. Guidelines on International Protection No. 9: Claims to Refugee Status Based on Sexual Orientation and/or Gender Identity within the Context of Article 1A(2) of the 1951 Convention and/or Its 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Available online.

Wasif, Sehrish. 2017. Transgender Community Barred from Hajj, Umrah. The Express Tribune, December 17, 2017. Available online.

Young, Leslie. 2017. Canadians Travelling with Gender-Neutral Passports Could Face Problems Abroad. Global News, August 25, 2017. Available online.