Top 10 Migration Issues of 2021

The rollout of vaccines, increased testing, and other public-health measures led several parts of the world in 2021 to begin recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. But the virus and its variants abated in fits and starts. As a result, 2021 did not see a return to pre-pandemic migration trends, but instead witnessed new patterns of movement in some places. At the same time, new conflicts erupted in 2021, ongoing crises continued to smolder, and forcibly displaced migrants often found themselves stuck in the middle. Impacts of the pandemic were not responsible for all our Top 10 migration issues of the year, but the repercussions of the public-health crisis and related economic fallout were felt widely. Explore these and other issues in our annual countdown.

Click the links below to navigate to each issue:

1. World Reopens Unevenly after First Year of Pandemic as It Reckons with Delta and Omicron

5. Biden Struggles to Dismantle Trump-Era Border Restrictions

6. As Government in Afghanistan Falls, Mass Evacuation of Afghans Occurs

7. At Europe’s Edge, "Weaponizing" Migration for Geopolitical Aims

8. Migration Streams through the Western Hemisphere Diversify

9. The United States Joins Europe in Focus on "Root Causes" of Migration

10. Remittance Flows Beat the Odds to Grow Despite Pandemic

Issue No. 1: World Reopens Unevenly after First Year of Pandemic as It Reckons with Delta and Omicron

In fits and starts, 2021 saw the globe reckon with the COVID-19 pandemic and the Delta and Omicron variants that emerged during the year by finding ways to open borders to at least some arrivals. One year after every single country in the world imposed some sort of border restriction in an effort to halt the virus’s spread, many started to roll these restrictions back, at least in part. Efforts were complicated by the rapid spread of the more infectious Delta and Omicron variants, but over the course of 2021 blanket travel restrictions began to give way to approaches that condition entry on certain requirements. Chief among these are health protocols that require travelers to offer proof of vaccination and provide a negative COVID-19 test before entry or complete a period of quarantine.

However, the transition was often not coordinated, smooth, or equal. The European Union issued a nonbinding recommendation in June for its Member States to lift their bans on nonessential travel, but individual governments adopted their own schedules. In general, countries mostly changed their rules for entry on their own terms, with little global coordination or under the aegis of an international body such as the United Nations or even between close allies. The United Kingdom allowed some vaccinated travelers to skip quarantine in August, but the United States only began accepting vaccinated Brits in November, the same month that Australia began granting entry only to its citizens and permanent residents abroad. In many cases the easing of border restrictions was prompted by economic calculus: hunger for tourism and international business. Some Caribbean countries began keeping their borders open in mid-2020, and Argentina and Chile abandoned their quarantine requirements in time for the southern hemisphere’s summer.

Generally speaking, land borders were much slower to open than airports and seaports. This created bizarre situations such as the one along the U.S.-Mexico border, in which an individual could easily fly from one country to the other but was unable to walk or drive across the border, splitting tight-knit crossborder communities and economies. Often, this arrangement privileged travelers who were wealthy enough to be able to afford plane tickets. And in some places, blanket restrictions persisted. China, for instance, plans to keep its limitations in place through mid-2022.

Partly as a result of this uneven reopening, movement on the whole remained a fraction of its pre-pandemic rate. In September, demand for international air travel was down 69 percent compared to 2019. Many parts of the world will likely not see tourism at 2019 levels until at least 2023, according to United Nations estimates.

Issue No. 2: In Landmark Integration Move, Countries in South America and the Caribbean Extend Protections to Millions of Venezuelans

Seven years after economic and political crisis spurred the start of large-scale flight from Venezuela, multiple countries in the region took significant steps in 2021 to provide legal status to millions of Venezuelan migrants and refugees. Leading the way was Colombia, where nearly all Venezuelan arrivals will be able to gain regular status under a landmark policy announcement in February that amounts to one of the most significant humanitarian acts in the region in decades. At the time the policy was announced, approximately one-third (1.7 million) of the 5.5 million refugees and migrants who left Venezuela lived in Colombia; the lack of legal status has left many stuck in the shadows. Under the new policy, those who entered by any means before February will be able to obtain temporary protected status for ten years, as will those who arrive legally by July 2023. Beneficiaries will be able to formally access education, job opportunities, and health care. Not surprisingly, uptake has been quite significant; more than 1.2 million Venezuelans had completed the first part of the registration as of September.

Next door, Ecuador in June announced a new normalization process for its approximately 420,000 Venezuelan inhabitants, around half of whom lack legal status. The effort mirrored a similar campaign in late 2019, which offered two-year humanitarian visas to many Venezuelans. Similarly, Peru in July unveiled a temporary protection regime for which more than 360,000 Venezuelans had preregistered ahead of time.

Similar efforts are underway in the Caribbean. A scheme introduced by the Dominican Republic in January offered renewable temporary protection to Venezuelans who had entered the country illegally since 2014; nearly 43,000 people applied during the one-month registration period. Curaçao, which has a much smaller Venezuelan population, offered one-year residence permits to migrants who legally entered the country before March 2020. Trinidad and Tobago previously introduced a regularization scheme in 2019 that provided temporary legal status to approximately 16,500 Venezuelans; re-registration was opened for one month in 2021.

Finally, the United States offered Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to Venezuelans already in the country as of March 9. The designation, which had been a campaign promise of President Joe Biden, offers protection from deportation to an estimated 323,000 Venezuelans lacking legal status, until September 2022.

The moves represent a response to multiple factors, not least the recognition that Venezuelan migrants and refugees will remain in their host countries for a period of years and therefore their fuller integration into society is important. The actions also are motivated by efforts to better document residents, identify those in need, and bolster nationwide defenses against the COVID-19 pandemic such as by vaccinating more people. In some cases, the policies reduce strain on overwhelmed asylum systems and acknowledge the challenges in large-scale deportations of illegally present migrants. They also serve to undermine the Venezuelan government (a geopolitical rival of many political leaders). These policies represent a major development in the international response to the hemisphere’s most severe and protected migration crisis.

Issue No. 3: Increasingly, Vaccination Is Becoming a Necessary Ticket to Travel, Challenging Those Who Lack Access

Requirements that travelers provide proof of vaccination as a condition for entry date back decades, mostly for countries with significant yellow fever transmission. But in 2021, the idea gained new life in countries around the world. As governments rolled back required quarantines and other border restrictions imposed earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic, they often have done so only for travelers who can show proof of vaccination against the novel coronavirus.

Unlike efforts by national and local governments to require vaccine “passports” to access businesses and other institutions, which often prompted stiff resistance, the imposition of this new vaccine mandate for international travel has received little domestic pushback. These policies have, however, led to concerns about equity in terms of who has access to COVID-19 vaccines, which vaccine, and who administers it. For one, although vaccines have been easily accessible in many wealthy countries, there remains a global scarcity, and barriers have often been particularly acute for migrants and refugees. More than 50 countries missed a target set by the World Health Organization (WHO) for vaccinating 10 percent of their populations by the end of September. Most of them were in Africa, where the continent-wide rate of vaccination remained less than 8 percent as of early December. The WHO’s goal of vaccinating 40 percent of people in all countries by the end of 2021 appears out of reach. Many factors are to blame, including rolling out vaccine distribution in persistent conflict- and crisis-affected places such as Afghanistan and Haiti, as well as difficulties accessing drugs through the global Covax scheme. As result, the WHO’s emergency committee opposed vaccine requirements for travel, although wealthy countries have largely instituted them all the same.

Even for individuals able to be vaccinated, not all drugs are considered equal. The WHO had only approved eight COVID-19 vaccines as of mid-December. As such, the millions of people who obtained jabs of Russia’s Sputnik V and other unapproved serums do not count as vaccinated under rules from the United States, Canada, and other countries. In the United Kingdom, where shots are administrated also matters: Rules rolled out in September do not recognize vaccinations administered to individuals in certain countries, many of which are in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, even if the drug itself has been approved.

Often, countries are offering alternatives for unvaccinated arrivals, including requiring individuals to undergo quarantine and testing for COVID-19. But the costs for these measures—which could include weeks in a hotel or other quarantine location—tend to be passed along to the individual traveler, which poses an additional barrier to mobility. Going forward, the slow pace of vaccine rollout globally suggests there may be a yawning gap in the people who can travel internationally and those who cannot.

Issue No. 4: New Crises Around Globe Add to Existing Humanitarian Burden and Destabilize Countries of First Asylum

The civil war in Syria entered its second decade in 2021, with continued dire conditions for millions of refugees, internally displaced people, and others. In all, about half of Syria’s prewar population has been forced to flee—sometimes multiple times. Elsewhere, Yemen retained its status as the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, and continued to be engulfed in conflict. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, persistent humanitarian crisis was exacerbated in the east by the volcanic eruption of Mount Nyiragongo, displacing hundreds of thousands. Extreme flooding in South Sudan was the worst in decades, affecting 700,000 people in a country still struggling with widespread insecurity.

Millions of people affected by these and other crises were joined in 2021 by new situations demanding urgent attention. The Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan will likely have long-running implications for that country and its neighbors. So too will conflict between the Ethiopian government and opposition groups in the Tigray region, which displaced more than 2 million people early in the year and led to famine-like conditions. Onset of drought is also exacerbating risk of hunger in East Africa. Meanwhile, an escalation of conflict between militants and government forces in northern Mozambique displaced vast swaths of the population. The February military coup in Myanmar led to a new crackdown against civilians and left millions in need of humanitarian assistance.

In several cases, many of the people affected by crisis were refugees and others who had previously been forcibly displaced, either internationally or within their own country’s borders. In Ethiopia, a pair of camps housing mostly Eritreans were closed after the refugees were allegedly targeted for horrific abuses by Eritrean forces and Tigrayan militias. As Lebanon descended into dire economic crisis, the approximately 1.5 million Syrian and other refugees were among the hardest hit, with the vast majority resorting to begging, borrowing money, or declining health services and education. Dozens of African migrants were killed in Yemen in March when a fire allegedly set by Houthi militants engulfed an overcrowded detention facility. And ongoing instability across countries of the Sahel repeatedly ensnared forcibly displaced people and the aid groups trying to assist them.

Situations such as these demonstrate the strain placed on host countries, which was one of the items the Global Compact on Refugees is intended to address. In many situations in 2021, impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, including deteriorating economic conditions, aggravated challenges. Going into the year, the number of people needing humanitarian assistance increased by 40 percent over 2020. While development has grown, funding overall remains meager. Through October, humanitarian aid was just 39 percent of what was needed, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). Startlingly, funding was slightly lower than at the same point in 2020, at the height of the pandemic, even though need has risen.

Issue No. 5: Biden Struggles to Dismantle Trump-Era Border Restrictions

U.S. President Joe Biden entered office in early 2021 with a sweeping plan to roll back the restrictive immigration policies of his predecessor, Donald Trump. The change in administration represented a new posture towards migrants that was difficult to overstate; Trump had taken up the mantle of immigration restrictions more fervently than any U.S. president in decades, while Biden’s political coalition depended in part on progressive activists who had urged a moratorium on deportations and pathway to citizenship for the country’s estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants.

The transition has led to a significant pendulum swing in some areas. The Biden administration scaled back immigration enforcement in the U.S. interior, made immigration benefits easier to access, took steps to begin to revamp parts of the asylum system, and called for an overhaul of immigration law that includes legalization for the unauthorized population. The new administration also expanded Temporary Protected Status (TPS) provisions for hundreds of thousands of individuals from multiple countries and raced to bring tens of thousands of Afghan translators, assistants, and others to the United States as the Taliban swept through the country.

Yet at the border, core elements of Trump’s policies remained in place, pointing to the limited ability of any White House to upend immigration law without assistance from other branches of government. The once obscure public-health provision Title 42, which the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) enacted in 2020 to allow the government to immediately expel even migrants seeking asylum, was a policy that the Biden administration has continued to implement and defended in court. Critics including senior public-health officials have said the policy lacks sound epidemiological grounding, particularly after the U.S.-Mexico border reopened in November.

More often, though, the Biden administration was prevented from making a clean break from Trump-era polices because of court orders, state resistance, and frayed institutional capacity. The administration was ordered in August to reimpose the “Remain in Mexico” policy, formally known as the Migrant Protection Protocols, although it has since renewed efforts to end it. Texas meanwhile assumed the role of chief foil to the administration, ramping up border enforcement activities and litigation to stymy Washington’s efforts. And despite a public tussle with Democratic lawmakers and activists over the limit for refugee resettlement, the United States in fiscal year (FY) 2021 resettled fewer than 11,500 refugees, the lowest number since the country’s resettlement system was formally created in 1980. Meanwhile, the temporary shuttering of U.S. consulates and other impacts of the pandemic contributed to the steady growth of the backlog for permanent residence, known as green cards, and processing of other immigration paperwork.

Issue No. 6: As Government in Afghanistan Falls, Mass Evacuation of Afghans Occurs

More than 122,000 people had been airlifted from Kabul by the time the U.S. military completed its withdrawal from Afghanistan amid a surprisingly fast takeover by the Taliban in August. Among the Afghan evacuees were former military translators, guides, and others who had worked with the U.S. and allied governments and contractors. The Biden administration has expected that 95,000 Afghans would come to the United States by September 2022, in the most dramatic postwar evacuation of its kind since the end of the Vietnam War. Thousands of others were brought to the United Kingdom, which has announced plans to accept up to 20,000 in coming years, as well as Australia, Canada, and countries across continental Europe.

An array of legal pathways was used for these evacuees, potentially requiring migrants and governments to navigate complicated systems to access benefits and ultimately permanent residence. In the United States, tens of thousands of Afghans remained on U.S. military bases months after arrival. The largest group of Afghans in the United States was likely to be humanitarian parolees who were expected to seek asylum after arrival, though many also benefitted from the Special Immigration Visa (SIV) created for people who assisted the U.S. mission. The United Kingdom announced a new bespoke resettlement route for Afghans, modeled after a previous system for Syrians.

Despite the specific visa pathways, there were at times major bureaucratic delays in processing cases and acknowledged failures to evacuate tens of thousands of others who remained in Afghanistan and in danger for having worked with U.S. and allied forces. Even as communities have opened their arms to the new arrivals, integration challenges could be significant for Afghans who experienced trauma and other harms while fleeing their native country under duress.

Afghanistan’s neighbors, which for years have hosted the largest number of Afghan refugees, were also affected by the messy U.S. withdrawal, and many closed border crossings to prevent large numbers of arrivals. As of December, nearly 97,000 Afghans arrived in neighboring countries needing protection, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), adding to the 2.2 million refugees and asylum seekers already residing in Pakistan, Iran, and other neighbors. However, true numbers are likely to be higher; Iranian officials have said unofficially that between 100,000 and 300,000 Afghans may have arrived in Iran over the course of 2021.

Slightly farther afield, Turkey reinforced defenses along its eastern border with Iran to prevent unauthorized arrivals of Afghan and other migrants. Neighboring Greece, anxious about a repeat of the hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers and other migrants who arrived in 2015 and 2016, also solidified its barriers with Turkey.

The long-term consequences of the withdrawal are unknown, but the likelihood of dire conditions in Afghanistan—including the reality that millions of Afghans are facing famine as winter descends, brutal rule by the Taliban, and a growing economic crisis—could prompt new waves of humanitarian migrants in months to come.

Issue No. 7: At Europe’s Edge, "Weaponizing" Migration for Geopolitical Aims

Migration is rarely disconnected from issues of geopolitics. But around Europe’s periphery, 2021 saw countries take new steps to wield their management of migration flows as tools to achieve broader aims.

Most notably, tensions between the European Union and Belarus (and to some degree Russia, Minsk’s close ally) escalated after EU officials imposed sanctions on the Lukashenko government for diverting a May flight carrying a Belarusian dissident. In subsequent months, thousands of migrants attempted to illegally cross from Belarus into Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia, in what U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and others derided as a Belarusian government attempt to “weaponize migration.” Most of these migrants from Iraq, Afghanistan, or other countries far afield had traveled directly to Minsk from Iraq and were then helped to the EU border by Belarusian officials, according to reports.

In response, Poland built a razor-wire fence along the border, sent troops to secure it, and began efforts to build an 18-foot (5.5-meter) wall. Thousands of migrants were trapped in the middle and endured brutal conditions while camped out in a forest without adequate supplies as temperatures plunged. Several migrants died.

On the other end of the continent, Moroccan officials in May seemed to allow as many as 12,000 migrants to cross into the Spanish enclave city of Ceuta, in apparent retaliation for Spain’s offer of health-care treatment to the leader of the Polisario Front, a group that has spent decades fighting for independence of Western Sahara. Relations along the border cities have at times been uneasy in the past, but they deteriorated further amid economic challenges that followed the COVID-19 pandemic.

The episodes were not unprecedented, and were foreshadowed most explicitly in 2020, when Turkey ushered thousands of migrants to the Greek border in a bout of brinksmanship with EU leaders over a pre-existing migration deal and military operations in Syria. In some ways, these actions herald a new era in international relations: as the European Union and other significant migrant destinations enroll peripheral countries to manage flows under a growing focus on externalization, these border countries find themselves with new leverage.

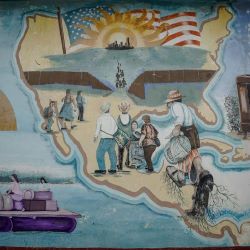

Issue No. 8: Migration Streams through the Western Hemisphere Diversify

South and Central America in 2021 were a throughway for a growing and increasingly diverse group of northbound migrants, some coming from Africa, Asia, and beyond. The treacherous Darién Gap in Panama has long served as a barrier for migrants seeking to cross South America into Central America, but was transited more than ever in 2021. The approximately 122,000 people who passed through the jungle as of the end of October was quadruple the previous record of 30,000 arrivals in all of 2016.

The migrants were from countries across the Americas as well as outside the region. The most prominent among them were tens of thousands of Haitians, many of whom had been living elsewhere in South America since the 2010 earthquake that leveled parts of Haiti. Brazil and Chile had been common destinations for these migrants in previous years, but recent economic, political, and social turns in those countries prompted many to set off again. In September, more than 15,000 Haitian migrants suddenly massed at a remote section of the U.S.-Mexico border, prompting U.S. officials to fly more than 8,500 on expulsion flights back to Haiti, where many had not lived in years. Although the numbers arriving at the U.S. border subsequently declined, thousands of Haitians continued to pass from Colombia into Panama during the fall.

Haitians were not alone. The year also saw new flows of migrants from Cuba, South America, sub-Saharan Africa, and elsewhere. Fiscal year (FY) 2021 saw a more than sevenfold increase compared to the prior year in U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) encounters of migrants from countries other than El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico. Notably, a significant share of these migrants were Black, which raised complicated questions in the United States and other countries grappling with issues of racial equity.

Migrants’ movement was a response to several factors, among them the imbalance in countries’ economic recoveries from the COVID-19 pandemic. While the United States and other wealthy countries bounced back, South America experienced the heaviest economic blow from the pandemic. Many migrants’ expectations that they would receive a warm welcome in the United States also seemed to be a factor in their movement.

In response, governments attempted alternatingly to coordinate and contain. Panama and Colombia struck a deal in August to limit the number of migrants able to cross the Darién, which mirrored the pre-existing “controlled flow” agreement between Panama and Costa Rica. Mexico has largely relied on trying to contain migrants in the south of the country and took to breaking up caravans of migrants to halt their passage, at times offering humanitarian visas and using other tactics to relieve pressure. While the United States had been the ultimate aim of many migrants, these efforts have prompted some to seek out new lives in Mexico and other countries that have been traditionally been used primarily only for transit, but where growing numbers of migrants are deciding to settle, perhaps permanently.

Issue No. 9: The United States Joins Europe in Focus on "Root Causes" of Migration

Efforts to address the so-called root causes of migration by tackling poverty, insecurity, impacts of climate change, and other issues in migrant-origin countries gained new momentum in 2021. Using economic development to curb irregular migration is a years-old proposition for Europe, most prominently through the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF) which launched in 2015. The efforts have evolved and grown more nuanced in recent years, and have recently adopted a less explicit migration focus such as with the new Neighbourhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI).

Across the Atlantic, U.S. President Joe Biden seemed to echo the European approach by restarting a previously intermittent effort by his country to focus on development in Central America. The $4 billion plan focuses on El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—in recent years the origins of the largest number of new irregular migration to the United States. The plan aims to use foreign assistance and other measures to target five elements at the root of regional migration: economic insecurity, corruption, threats to human rights, organized crime, and violence. The effort bore traces of the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, which was unveiled by President Barack Obama in 2014 but subsequently scaled back during the Trump administration. That earlier effort yielded mixed results, and the United States’ uneasy relationships with some Central American leaders suggests there may be challenges in the future.

The relationship between development and migration is complex and often indirect. While greater wealth may prompt some would-be migrants to stay in place, it may also give others the means to afford a journey that would have been otherwise impossible.

Yet the moves by the Biden administration suggest that leaders on both sides of the Atlantic have been persuaded by arguments that economic stagnation, corruption, and other factors contributing to emigration can be at least partially addressed by development assistance. This marks a change from just a few years ago, when leaders were more likely to embrace preventative measures such as the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” policy or efforts to bottle up asylum seekers and other migrants in Libya and Turkey. Although externalization of migration management remains a tempting tool to prevent some migrants from reaching European and U.S. borders—or quickly expel those who do—policies in 2021 also looked farther afield to conditions within migrant-origin countries.

Issue No. 10: Remittance Flows Beat the Odds to Grow Despite Pandemic

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the conventional wisdom was that international remittances would slow to a trickle. Migrants and diaspora members who had lost jobs due to the global economic downturn, the thinking went, would be unable to send money back to their countries of origin or ancestry, imperiling families and communities depending on those transfers.

But as in so many other areas, the pandemic created surprises. After a modest drop in 2020, remittances remained surprisingly strong in 2021, increasing by 7 percent to a total projected $589 billion sent to low- and middle-income countries. Money transfers were projected to have increased to every region of the world except East Asia and the Pacific and grew the most (by 22 percent) to Latin America and the Caribbean.

Why were predictions so wrong? In part, the strong remittances were in line with longer running findings that money transfers increase during times of crisis. While this logic tended to assume that the crisis was on just one end of the remittance system, affecting either the senders or receivers, the pandemic suggested that a similar phenomenon occurs when both sides are impacted. The swift economic recovery and government-led stimulus programs in the United States and Europe were other likely factors. So too was the increase in oil prices, which most affected senders in Russia and countries in the Middle East.

Another reason was that the costs of sending money dropped slightly as many services moved from cash- to digital-based systems. The significantly fewer travelers during the pandemic meant that fewer individuals hand-carried cash and goods; instead, more people sent money via digital platforms such as mobile money and online wallets. El Salvador embraced the notion wholeheartedly in September when it adopted the cryptocurrency bitcoin as legal tender, in part to reduce remittance costs (remittances account for around one-quarter of El Salvador’s gross domestic product, more than all but a handful of other countries). Still, mobile services represent a small share of the ways that people sent money, in part because they require a bank account. The costs of sending remittances averaged 6.3 percent through the first six months of the year, more than double the 3 percent target set by the United Nations.

For countries and communities that received large amounts of remittances, the money was often a lifeline that served to meet subsistence needs and immediate expenses such as to buy food, pay for health care, and cover utilities.