You are here

Amid Record Numbers of Arrivals, Chile Turns Rightward on Immigration

Peruvian immigrants celebrate their country's Independence Day at a festival in Santiago, Chile. (Photo: Municipalidad de Santiago)

One of South America’s most stable countries economically and politically, Chile has become an attractive destination for migrants from the Americas and other regions. Following the country’s emergence from dictatorship in 1990, the foreign-born population increased more than four-fold, to nearly 478,000 in 2016. The pace of arrivals has quickened in recent years: Between 2010 and 2015, immigration to Chile grew at a faster rate than anywhere else in Latin America. While the immigrant share of the total population in Chile remained small in 2015, at just under 3 percent, it was surpassed in the region only by that of Argentina and Venezuela.

International migration to the predominantly European-descent Chile has also grown racially diverse, as the origins have shifted. Chile received growing numbers of Peruvians and Bolivians starting in the 1990s, and Haitians, Colombians, and Venezuelans in the 2000s and 2010s, while the share of Argentines and Europeans has fallen. This diversification in general, and the influx of tens of thousands of African-descent Haitians in particular, has made immigration more visible as an issue and has provoked public backlash, echoing calls for greater restriction in the United States and Europe. For the first time in recent history, candidates from the main political coalitions openly called for a halt in immigration or more restrictive policies ahead of the November 2017 elections.

The uptick in immigration has also renewed demands from both left and right to reform the country’s Immigration Act of 1975, a holdover from the dictatorship era that many argue is no longer adequate to manage an increasingly dynamic situation. While center-left President Michelle Bachelet spearheaded several progressive initiatives expanding services to immigrants, her attempt to replace the 1975 law fell victim to scandal and growing partisanship. With her constitutionally limited time in office ending in March 2018, and with her successor, center-right billionaire and former President Sebastián Piñera, proposing greater restrictions, immigration policy could well take a turn.

This article examines recent shifts in the foreign-born population in Chile, outlines earlier attempts to reform the dictatorship-era law, and discusses how a new Piñera administration may approach immigration.

From Migrant Sender to Regional Destination

Since the end of World War II, Chile has been a country of emigration, and what little immigration it experienced until recent decades was largely European. Under the repressive dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet, installed via military coup in 1973, more than 500,000 Chileans fled or left voluntarily. Few migrants chose to settle in Chile during this time, and the immigrant population fell to a historic low of 84,000—less than 1 percent of the population—in 1982.

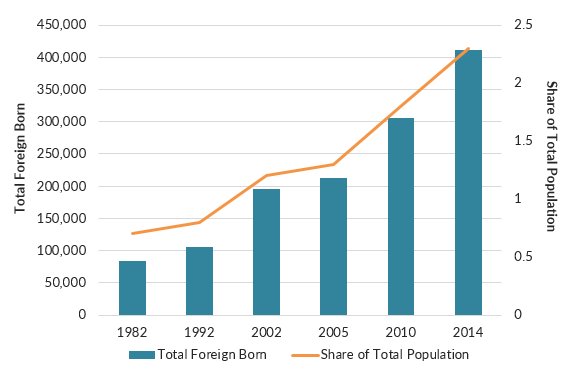

The end of the dictatorship in early 1990 marked the beginning of a new era of migration to Chile. The country’s transition to democracy and its growing economic stability, particularly amid deteriorating conditions elsewhere in the region, made it an attractive destination for migrants from countries including Argentina, Peru, and Bolivia. By the 1992 Census, the foreign-born population had increased nearly 36 percent from 1982, surpassing 105,000 people (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number and Share of Immigrants in Chile, 1982-2014

Notes: Figures for 1982, 1992, and 2002 are decennial Census data, while those for 2005, 2010, and 2014 are estimates based on visa data from the Department of Foreigners and Migration (DEM). The failure of Chile’s Census in 2012 left the country without its most reliable source of immigration data; because DEM tracks administrative actions rather than individuals, its data may overcount or undercount certain populations.

Sources: Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, “Censos de Poblacion y Vivienda,” accessed January 4, 2018, available online; and DEM, Migración en Chile 2005-2014 (Santiago: 2016), available online.

As immigration from neighboring countries continued to increase throughout the 1990s, public concern grew. Media outlets increasingly portrayed these flows in a negative light, and the economic crisis of the late 1990s further enflamed unfavorable attitudes. These trends led President Eduardo Frei to hold a regularization process in 1998 that granted temporary visas to roughly 23,000 unauthorized immigrants and residency permits to another 18,000, both primarily from Peru and Bolivia. The foreign-born population continued to grow in the 2000s, reaching 195,000 in 2002—its highest level in roughly a century—and 300,000 people in 2010, the vast majority from neighboring countries.

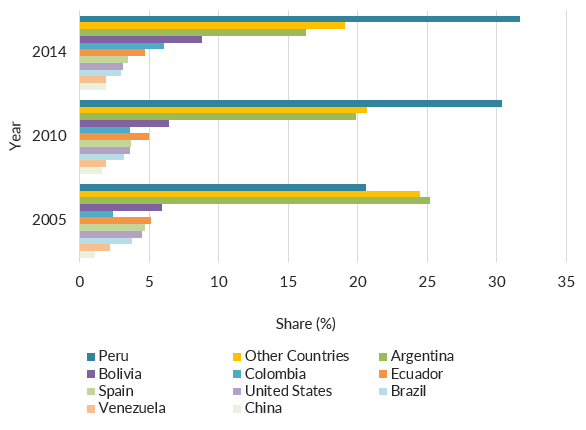

Notably, the composition of the immigrant population in Chile changed significantly between 2005 and 2014 (see Figure 2). Peru overtook Argentina as the largest source country, accounting for roughly one-third of all immigrants in 2014, and the share from Colombia tripled.

Figure 2. Top Origin Countries by Share of Immigrant Population in Chile, (%), 2005, 2010, 2014

Source: DEM, Migración en Chile 2005-2014.

Meanwhile, data on new permanent residency permits granted between 2005 and 2014 show a slightly different picture. While the largest number went to Peruvians in 2014, their share decreased significantly from 2010. Bolivians, Colombians, and Spaniards show large relative increases, and most interestingly, the share for Dominicans grew from almost zero to 3 percent, and for Haitians from zero to 2 percent.

Arrivals of Haitians in particular have picked up in recent years. Following the 2010 earthquake that leveled large swaths of Haiti, Chile granted increasing numbers of residency permits and visas to Haitians fleeing the devastation. Prior to 2010, residency permits to Haitians rarely surpassed 50 per year; by 2015, the number exceeded 1,100. The growth in numbers of temporary visas given to Haitians was even more significant: from roughly 300 in 2009 to nearly 8,900 in 2015. Overall arrivals surged in 2016, when roughly 44,000 Haitians entered Chile, many arriving as tourists.

Old Problem, New Urgency

The influx has renewed longstanding calls to replace the Immigration Act of 1975, which today remains the only law on the books regulating visa administration. Political actors, civil-society organizations, and the public broadly agree that the law should be changed, though their reasons vary. Some argue the law is a relic of the Cold War and dictatorship, viewing immigrants as threats to national security. For others, it leaves too much open to interpretation and facilitates illegal immigration by allowing foreigners to enter the country as tourists, overstay their permits, and then obtain a temporary visa—as is the case with many Haitians today. For still others, the law does not adequately address concerns associated with recent inflows, including integration. Despite these wide-ranging justifications for change, political gridlock and lack of urgency have stymied previous attempts at reform.

“Policy of No Policy”

Because the Immigration Act focuses on regulating entrances, it has allowed the government to develop one-off initiatives on urgent matters—such as health-care access for pregnant immigrants—without changing the national security core of the law. Known as the “policy of no policy,” this phenomenon leads to a paradox where the current law, which is intrinsically conservative in nature, coexists with a patchwork of more expansive administration-led policies. More importantly, the fact that these directives are not approved by Congress makes it very easy for a new government to change or eliminate them.

During her first period in office (2006-10), center-left President Bachelet pioneered the approach of using presidential directives to manage migration. She worked to enshrine Chile as open to immigration, most notably by signing Presidential Directive No. 9 in 2008, Chile’s most progressive policy concerning immigrants at the time. It defined Chile as a welcoming country opposed to discrimination, and consolidated two key agreements that the Department of Foreigners and Migration (DEM in Spanish) had reached with other offices: to secure access to public health care for children and pregnant women, and to provide public education for all children, regardless of migration status. Congress also approved a new refugee law and a regularization program that granted residency permits to about 30,000 immigrants. However, Bachelet left office with the 1975 law still intact.

In 2010, for the first time in two decades, the center-left coalition that defeated Pinochet lost the presidency, to a right-wing coalition headed by Piñera. The Piñera administration (2010-14) did not change or rescind Bachelet’s immigration directives. Its immigration reform proposal aimed to link migration to economic development and attract mostly highly skilled immigrants. Meanwhile, low-skilled migrants, according to this proposal, would push more Chileans, particularly women, into the skilled workforce. The plan was widely criticized by migration scholars and civil-society organizations, and Congress ultimately did not take it up.

“State of Mind Policy”

Other critics of the 1975 law point out that expanding rights to migrants at the national or local level, without changing the underlying law, results in a “state of mind policy.” Over the last five years, municipalities, or comunas, have developed initiatives on integration, in which local offices provide services to immigrants in the areas of housing, health care, and education. In this context, immigrant access to social goods depends solely on the public worker or official at the door to administer them, and results can vary accordingly.

Without a law to protect these initiatives, they are vulnerable to changes and turnover in local government, and may even be disbanded. This was the case following local elections in 2016, when at least two of the largest immigrant-receiving comunas restructured these offices to reduce their role in immigration.

Movement During Bachelet’s Second Term

When Bachelet assumed the presidency for the second time in 2014, she promised to develop a comprehensive approach to immigration that would address the growth in arrivals and their integration into society. An official governing plan laying out her administration’s priorities proposed that Chile would take “an active role on humanitarian resettlement, legal residency, protection of human-trafficking victims, and development of immigrants” and to accomplish this, would “consider changes to migration-related legislation to change the current perspective of security and migration management into a perspective of inclusion, regional integration, and human rights.” Despite these ambitions, migration was largely sidelined in the administration’s legislative efforts, which focused on other progressive reforms, including rewriting the Chilean constitution, protecting workers, reforming retirement funds, and relaxing the abortion ban.

Marking a continuation with her earlier period in office, in November 2015 Bachelet published Presidential Directive No. 5, which laid out guidelines for an immigration reform bill planned for 2016. The administration proposed reforming DEM and adding migration-related units within each ministry; promoting immigrant participation in the development of policies affecting them; and expanding immigrants’ social safety net and access to public goods and services. Before being sent to Congress, the proposed law had to be discussed with each of the ministries. The original proposal stalled at this stage, exposing the differences in opinion on migration among the political actors involved, particularly regarding the cost of the law and the role of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. These disagreements halted the bill’s progress and hung over the administration throughout 2016.

By July 2017, the debate over the measure had reached a new level of urgency. In August, after much delay—and while dealing with criticism from the opposition, pushback from the Ministry of Interior, and the resignation of the head of DEM—the administration finally sent a watered-down proposal to Congress. Not only did the plan fail to incorporate the details outlined in Bachelet’s governing plan, but it reached the legislature less than three months before the presidential election in November 2017, and less than seven months before the end of Bachelet’s administration—leaving scarce time for passage or implementation. Further, most migration scholars and civil-society organizations disagreed with the legislation. Critics argued that the proposal did little to move beyond the 1975 law’s security framework, as it included the creation of a migrant registry and would allow the government to refuse entry on the grounds of public health and national security.

Though the measure departed from the Bachelet administration’s stated immigration goals, it is notable for being a rare effort to change Chile’s “policy of no policy” and the “state of mind policy” approaches. However, while the administration can claim a number of victories on progressive issues, it seems immigration reform will not be among them. As the administration prepared an agenda of topics to be discussed by Congress in its final two months, immigration was left off the list, leaving Bachelet’s successor to put his imprint on discussions over replacing the 1975 law.

An Increasingly Politicized Debate

As Bachelet’s experience demonstrates, the immigration debate in Chile has succumbed to increasing politicization, despite the fact that immigrants comprise a relatively small share of the total population. Over the last two decades, public discourse has been highly reactive to changes in flows, and more recently to pressure from political parties, civil-society organizations, public perceptions, and media representations of immigration. These tensions have come to a head in the last few years, as immigration has emerged as a hot-button issue. A well-reputed survey in spring 2017 showed that 41 percent of Chileans believed migrants increased crime, a 6-point uptick from the last poll in 2003, and just one-third agreed that immigrants were good for the economy.

Immigration was a topic of fierce political debate in the lead-up to the October 2016 municipal elections. In some larger immigrant-receiving regions, such as Antofagasta in northern Chile, candidates openly argued that immigration needed to be stopped and, as others have done before them, connected immigrants to prostitution, delinquency, and other social ills. The right-wing coalition Chile Vamos won the largest number of mayoral races and the overall vote count, while maintaining or regaining control of some of the municipalities with the largest number of immigrants.

During his 2017 bid for a new term, Piñera—at the time the most hardline candidate on immigration with a chance of winning—stated that he favored tighter border controls, meaning he would either present a new proposal with stricter requirements for entry, or revive the proposal he sent to Congress in 2013. Nueva Mayoría’s candidate, Alejandro Guillier, was seen as most likely to continue with Bachelet’s proposal, though he called for immigration to be “more selective” and took other restrictive stances. Beatriz Sánchez of Frente Amplio had the most progressive approach to immigration including recognizing migration as a constitutional right.

The November election results proved surprising: A divided electorate gave Piñera roughly 36 percent of the vote—less than expected and lower than the 50 percent required to avoid a runoff. Guillier came in second with close to 23 percent, positioning the two candidates with the more restrictive immigration approaches to face off in the second round in December. Meanwhile in Congress, fragmentation among the left combined with gains on the right mean that the center will hold the key to any significant policy change.

While Piñera’s win in the runoff was largely expected, his 9-point margin of victory surprised observers. Piñera won in part by successfully mobilizing right-wing voters who had sat out the first round. Preliminary analysis suggests that the backing of far-right independent candidate José Antonio Kast, who had made immigration control a key part of his campaign with calls for physical barriers along the Peruvian and Bolivian borders, gave Piñera the ultimate advantage—particularly amid lower turnout and divisions on the left.

A New Era of Immigration Control?

In terms of immigration, the new administration will likely have the support needed to fulfill Piñera’s promises—signaling an era of increased immigration control. While his platform proposes developing an immigration policy through dialogue, the experience of his first term shows this is unlikely to be the case. The new administration will likely impose limits on immigrant access to social services, streamline immigration controls, and improve registration and information systems. While it plans to maintain access to education for all children, in a shift from current policy it aims to restrict equal access to health care by reserving it only for authorized immigrants. At the same time, Piñera has signaled he will renew the focus on skilled immigration from his 2010 bill, facilitating foreign degree recognition and the provision of visas for skilled labor.

While Piñera’s tone on immigration has clearly hardened since his first term, it remains to be seen how this shift will be borne out in his policies. His governing plan proposes to “integrate those immigrants who abide by Chilean laws and collaborate with Chile’s development,” adding the law-abiding component to his 2010 focus on skilled immigration. This might imply that his earlier bill will be thoroughly revised to include considerations for particular nationalities, for example restricting Haitian immigration—a goal of some extreme-right groups—and facilitating skilled Venezuelan immigration—in clear opposition to Venezuela’s government.

Meanwhile, Piñera’s victory marks another step in South America’s broader right turn, as the “pink tide” of left-wing governments fades amid disillusionment and discontent with establishment candidates. With countries newly adopting or discussing restrictive immigration policies, the role that immigrants will play in South American societies for years to come is increasingly up for debate.

Sources

Bachelet, Michelle. 2013. Programa de Gobierno Michelle Bachelet 2014-2018. Accessed November 8, 2017. Available online.

Centro de Estudios Públicos. 2017. Encuesta Nacional de Opinión Pública, Abril-Mayo 2017. Accessed December 10, 2017. Available online.

Departamento de Extranjería y Migración de Chile (DEM). 2016. Boletín Informativo No. 1: Migración Haitiana en Chile. Santiago: DEM. Available online.

---. 2016. Migración en Chile 2005 - 2014. Santiago: DEM. Available online.

---. 2017. Anuario Estadístico 2015. Santiago: DEM. Available online.

Doña Reveco, Cristián and Brendan Mullan. 2014. Migration Policy and Development in Chile. International Migration 52 (5): 1–14.

González, Valentina. 2017. En Solo Siete Meses la Inmigración Haitiana a Chile Ha Superado el Total del Año Pasado. El Mercurio, August 2, 2017. Available online.

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. N.d. Censos de Poblacion y Vivienda. Accessed January 4, 2018. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2017. IOM Helps Chile to Prepare New Migration Policy. Press reléase, IOM, January 24, 2017. Available online.

Martin, Karina. 2017. Chile Experiencing Highest Immigration Growth In Latin America. PanAm Post, May 29, 2017. Available online.

Ministerio de Desarrollo Social de Chile. 2016. CASEN 2015: Inmigrantes, Principales Resultados. Presentation given on December 21, 2016. Available online.

Organization of American States (OAS). 2015. International Migration in the Americas: Third Report of the Continuous Reporting System on International Migration in the Americas (SICREMI). Washington, DC: OAS. Available online.

Piñera, Sebastián. N.d. Nuestras Propuestas. Accessed December 1, 2017. Available online.

Presidential Cabinet of Chile. 2015. Lineamientos e Instrucciones para la Política Nacional Migratoria. Presidential Directive No. 005/2015. Available online.

---. 2008. Imparte Instrucciones sobre la “Política Nacional Migratoria.” Presidential Directive No. 009/2008. Available online.

Rojas Pedemonte, Nicolás and Claudia Silva Dittborn. 2016. La Migración en Chile: Breve Reporte y Caracterización. Madrid: Universidad Pontificia Comillas, OBIMID. Available online.

Sandoval Ducoing, Rodrigo. 2017. Una Política Migratoria para un Chile Cohesionado. In La Migración Internacional como Determinante Social de la Salud en Chile: Evidencia y Propuestas para Políticas Públicas, eds. Báltica Cabieses, Margarita Bernales, and Ana María McIntyre. Santiago: Universidad del Desarrollo.

Santiago Times. 2017. Presidential Candidate José Antonio Kast Wants to “Reconstruct” Chile. Santiago Times, September 14, 2017. Available online.

Stefoni, Carolina. 2011. Ley y Política Migratoria en Chile: La Ambivalencia en la Comprensión del Migrante. In La Construcción Social del Sujeto Migrante en América Latina: Prácticas, Representaciones, y Categorías, eds. Bela Feldman-Bianco, Liliana Rivera Sánchez, Carolina Stefoni, and Marta Inés Villa Martínez. Quito, Ecuador: FLACSO.

Thayer Correa, Luis Eduardo and Durán Migliardi, Carlos. 2015. Gobierno Local y Migrantes Frente a Frente: Nudos Críticos y Políticas para el Reconocimiento. Revista del CLAD Reforma y Democracia 63: 127-62. Available online.