You are here

Australia: A Welcoming Destination for Some

An array of Chinese lanterns adorn the Sydney Harbour Bridge area, in recognition of Chinese New Year. (Photo: Jonathan O'Donnell)

For more than two centuries, extensive immigration has underpinned economic and social development in Australia. The immigrant share of Australia’s population is high, at 28 percent, and the foreign-born population has grown more diverse over time as the country amended immigration policies that once favored newcomers from European countries. In addition, Australia ranks third among refugee resettlement countries, after the United States and Canada, having resettled more than 840,000 people since 1947.

Yet, over the last decade and a half, political attention has largely focused on the few thousand asylum seekers who have attempted to enter the country illegally by boat. Large numbers of asylum seekers—often in unseaworthy fishing vessels—first arrived in the mid-1970s, following the end of the war in Indochina, but the contemporary debate dates to 2001. In August of that year, the government refused to allow a Norwegian freighter, the MV Tampa, to enter Australian waters to unload more than 400 Afghans and Iraqis it had rescued from a sinking ship. The ensuing standoff drew international attention to the government’s hard line toward individuals sailing to Australia from Southeast Asia in hopes of gaining asylum.

Almost two decades on, Australian policymakers continue to advance controversial policies to discourage unauthorized boat arrivals and deter the smugglers who transport them, including an offshore detention policy that has been widely criticized by domestic human-rights advocates and the international community. Despite this condemnation, Australia’s leaders remain proud of their approach and have held it up as a model for other regions facing high levels of irregular immigration. During the 2015-16 migration crisis in Europe, former Prime Minister Tony Abbott traveled to London to talk up the strict border controls and boat turnbacks that had been a hallmark of his time in office, advising European policymakers to follow Australia’s example in order to reestablish order and build public confidence in migration management.

By the beginning of 2018, Australia’s continued use of offshore detention centers in Nauru and on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea (PNG) continued to draw major criticism internationally and domestically. In 2016 the PNG Supreme Court declared the Manus Island center illegal and demanded it be closed. Though Australia shut down the facility in late 2017, the majority of arrivals remain on Manus in specially built accommodations where they remained in legal and socioeconomic limbo without any major change in their circumstances.

To place these debates in context, it is necessary to consider Australia’s ongoing and far less politically divisive policies on immigration more broadly, including the handling of asylum claims by individuals after their legal arrival in Australia. This article examines historical and contemporary migration trends and debates in Australia, before considering why the debate over spontaneous maritime arrivals has become so contentious. In doing so, it shows that Australia is emblematic of the policy challenges many countries confront, including those generally supportive of international migration.

Becoming a Diverse Destination

Since European settlement began in the late 18th century, overwhelming the indigenous population, immigration has played a major role in Australia’s population growth—in many periods comprising more than half of the annual increase. Between the end of World War II and 2016, the Australian population more than tripled, from 7.4 million to 24.2 million. Twenty-eight percent of Australian residents in 2016 were born overseas—the largest share in more than 120 years. Adding in those with at least one foreign-born parent, nearly half the population is either an immigrant or the offspring of immigrants.

Australia regards immigration as a major nation-building project, in which the government has taken the lead by devising entry and selection policies as well as providing financial assistance to encourage immigration. One of the most significant changes has been a shift away from the preferential treatment of British migrants and toward a nondiscriminatory selection policy in the latter part of the 20th century. Another has been an increasing emphasis on economic selection criteria—for both permanent and temporary migrants—at the expense of permanent family migration, which has been a focus of the migration program since the 1800s.

End of White Australia

In the second half of the 19th century, concerns grew about competition on the goldfields and other potential threats to the domestic workforce posed by low-wage migrant labor from Asia and the Pacific Islands, leading to discriminatory state laws and regulations. These culminated, shortly after Australia became a federation, with the passage of the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act. This law required a European language test as a means of restricting non-European migration—reflecting existing hostility to non-Europeans and forming the basis of what later became known as the White Australia Policy.

The raft of laws and policies associated with the White Australia Policy never completely excluded non-Europeans. Over time, provisions were made for certain Asian students, merchants, and workers with the language and professional skills needed by businesses and the families of businessmen. After World War II, various regulations central to the restrictionist policies were removed to allow increasing numbers of non-European immigrants to permanently settle in the country, and the White Australia Policy was formally replaced in the 1970s by selection without reference to ethnicity, gender, or religion. This shift also ended the preferential selection and access to Australian citizenship for British immigrants.

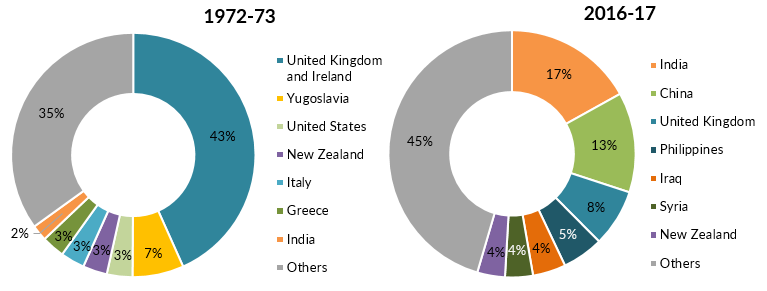

Figure 1. Top Origin Countries of Permanent Resident Arrivals in Australia, Fiscal Year (FY) 1972-73 and 2016-17

Note: The Australian fiscal year runs from July 1 to June 30.

Source: Australian Government Department of Home Affairs, “Historical Migration Statistics,” accessed February 9, 2018, available online; and Department of Immigration and Border Protection, “Permanent Additions to Australia’s Resident Population,” updated December 5, 2017, available online.

Changes in the major source countries reflect this shift to nondiscriminatory selection, as well as the impact of economic, social, and political circumstances in individual countries. In 1972-73, around the formal end of the White Australia Policy, 43 percent of all permanent arrivals were from the United Kingdom and Ireland, while India ranked eighth with 2 percent (see Figure 1). By 2016-17, Indians had taken the lead, constituting 17 percent of the 226,000 permanent arrivals, followed by Chinese (13 percent) and British (8 percent). Other non-European countries also grew in prominence, including the Philippines, Syria, and Vietnam. Underlying the diversity in the source countries are variations in the importance of the three main eligibility selection streams of family, skills, and humanitarian. The skill program is the primary channel for permanent arrivals from India, China, the United Kingdom, the Philippines, Pakistan, and South Africa; meanwhile, the family reunion program is the major route for those from Vietnam, and the offshore humanitarian program brings in the most Iraqis and Syrians.

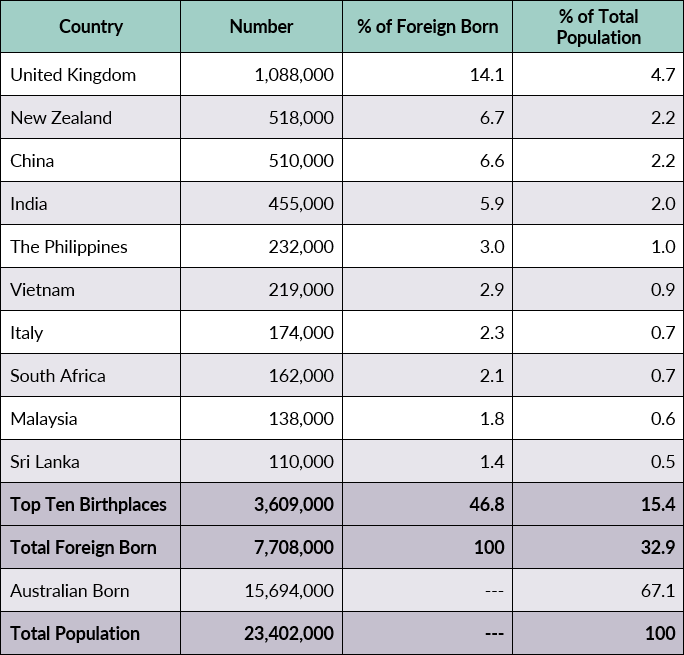

Table 1. Top Birthplaces of Australian Foreign-Born Population, 2016

Note: These figures exclude short-term visitors.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, “2071.0 Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia - Stories from the Census, 2016 - Cultural Diversity,” updated July 20, 2017, available online.

In 2016, among all foreign born, those from the United Kingdom and New Zealand were the two largest groups, accounting for roughly 21 percent of Australia’s nearly 7.7 million immigrants (see Table 1). The next four top countries of origin—China, India, the Philippines, and Vietnam—were all in Asia.

Economic Criteria in Permanent Migration

The adoption of a nondiscriminatory approach to admissions in the 1970s reshaped the Australian immigration system in a number of important ways. Today, migrants are selected for permanent residence on one of three main grounds: family reunion, economic benefit, or humanitarian need. The numbers of entrants in each of these streams is based on an annual quota determined after consultations with the individual states, community groups, and economic stakeholders.

Australia follows the Canadian practice of using a points system to weigh and adjudicate applications for admission as an economic immigrant, with criteria reflecting changing emphases on age, family ties, language, education, work experience, and occupation. Since the introduction of the Numerical Multifactor Assessment Scheme (NUMAS) in 1979, the system has favored younger, skilled migrants with knowledge of English—the type of workers required as Australia restructured its economy to better cope with the challenges of globalization, by moving toward knowledge-based industries and away from manual labor. Since the 1980s, special entry schemes have admitted investors and businesspeople, most recently emphasizing innovation and investment. Australia also uses an Employer Nomination scheme, which includes a Regional Sponsored Migration Scheme through which employers can fill vacancies with either permanent or temporary residents.

During the first decade of the 21st century, permanent resident admissions via the Migration Program—which excludes humanitarian arrivals and immigrants from New Zealand—peaked in 2008-09, with a total of 171,800 arrivals. In 2009-10 and 2010-11, the government reduced arrivals by 1.9 percent each year in response to the global financial crisis, as a strategy to avoid negative employment impacts on the population (though arrivals were still more than twice those during 1999-2000). Despite the economic crisis, 64 percent of permanent arrivals in 2009-10 (including dependent spouses and children) were admitted under the economic skilled migration program. In 2016-17, this figure increased to 67 percent of the 183,600 arrivals. These numbers illustrate the long-term trend of prioritizing economic over family criteria in selection, and the prominence of economic immigration reflects the robustness of the Australian economy—and, in particular, the labor needs of the booming resource sector.

The only country whose citizens do not need visas to enter Australia is New Zealand, with which Australia has a common labor market. Migration flows both ways between the countries in response to shifting economic conditions. In 2015, for the first time in 25 years, more Australians moved to New Zealand (25,300) than vice versa (24,500). Many New Zealanders in Australia work and live there on a temporary basis. However, in 2016-17, more than 8,000 New Zealanders entered Australia as permanent residents, nearly 4 percent of all arrivals.

Despite their country’s enormous landmass, Australians have historically settled in heavy concentrations around the coast, especially in the six state capital cities. The two largest, Sydney and Melbourne, are collectively home to more than one-third of the population. Not surprisingly, such cities—with their employment opportunities and sociocultural resources—are attractive both to immigrants and the native born. The government has used immigration policy as one means to reverse this trend, by awarding extra points to would-be migrants willing to move to rural areas, while offering them better pathways to recognition of their professional qualifications. The presence of large numbers of foreign-born and -trained medical practitioners in rural Australia is one outcome of such policies.

The Expansion of Temporary Migration

Despite long-held concerns about the potential negative effects of temporary migration on labor market conditions for native-born workers, Australia has expanded opportunities for these flows. This change can be seen as part of the broader trend toward prioritizing economic considerations in Australian migration policies.

One form of temporary movement in particular, tourism, has played an increasingly important part in Australia’s foreign exchange earnings since the 1980s. Short-term arrivals have surged in recent years, particularly since 2012, and tourists accounted for three-quarters of these arrivals in 2016. At the same time, government support for education as an international trade initiative has led to a major expansion in the numbers of foreign students entering Australia. In May 2017, there were more than 502,000 international students in Australia, an increase of 14 percent from May 2016. More than half of all international students were from China, India, Malaysia, Nepal, or Vietnam. Australia’s growing popularity as an education destination can be partly attributed to policy changes that created opportunities for students to apply for permanent residence immediately after graduation. In 2016-17, about 55 percent of those granted permanent residence under the skills program had applied while in Australia.

Temporary workers have complemented student arrivals. During the 1990s, employer calls for greater flexibility in meeting skilled labor needs—particularly in the booming resource extraction industry—led to the adoption of policies increasing the admission of temporary skilled workers. One such policy was the 457 visa program, created to expedite the entry of highly skilled workers on four-year visas, and expanded over time to cover a wider range of occupations. Since its inception in 1996, the program has been the subject of several government reviews, largely substantiating allegations that employers exploited foreign workers and failed to demonstrate that they were using the scheme to fill legitimate skill shortages.

Seeking to address these concerns and shore up support from his right-wing critics, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced in April 2017 he was ending the program (though without affecting the 95,000 already holding 457 visas) and replacing it with Temporary Skilled Shortage (TSS) visas. There are two forms of the TSS visa: a two-year visa and a separate four-year visa requiring stronger English and other skills. Both types will require applicants to have at least two years of relevant work experience, and require employers to pay wages at the labor market rate. The list of qualifying occupations was also cut significantly, especially for the four-year visa which alone provides a pathway to permanent residence.

Meanwhile, two other temporary worker programs have faced far less controversy. Motivated largely by diplomatic considerations, the Seasonal Worker Program has brought several thousand temporary workers each year from Tonga, Vanuatu, Timor-Leste, and other island nations since 2012 to work in the Australian horticulture industry. In addition, the Working Holiday Maker Program allows young people ages 18 to 30 from designated countries to enter Australia for up to 12 months of combined work and leisure. Participants are an important source of casual workers, especially in regional agriculture and in the hospitality and tourism industries. More than 214,000 visas were granted under the program in 2015-16, with the United Kingdom, Germany, and Taiwan comprising the top origins.

Humanitarian Admissions Program

Since World War II, recognition of humanitarian need has been one of the three Australian routes to permanent residence. Australia has long boasted of its acceptance of relatively large numbers of refugees, who are identified for resettlement by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. In 2016-17, Australia granted 24,162 visas under its humanitarian program, the highest intake on record. This includes 10,143 for refugees and 14,019 for “special humanitarian” cases, and makes Australia third among the world’s top resettlement countries, after the United States and Canada. It also committed to increasing its refugee quota to 18,750 in 2018-19. Separately, in 2015, Australia announced it would resettle an additional 12,000 refugees displaced by conflicts in Syria and Iraq, slots it filled by March 2017. As a result, in 2016-17 Syria and Iraq were among the top origin countries of Australia’s overall permanent resident arrivals, as shown in Figure 1.

Australia’s geographic isolation has meant that large numbers of asylum seekers have rarely crossed its borders without legal authorization. The majority of migrants seeking asylum have instead entered Australia legally on short-term entry visas. While waiting to have their refugee claims processed these people can remain but are only allowed to work in special circumstances, and as a result many depend on a range of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and community groups for their daily needs. Chinese students in Australia at the time of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre represent one of the largest groups of successful asylum seekers. By July 1994, a total of 42,000 had been granted permanent residence.

Boat Arrivals Test Australia’s Generosity

In contrast to refugees who are admitted for resettlement or those who seek humanitarian protection after legally entering Australia, the government’s handling of asylum seekers who arrive by boat without authorization has been contentious. For nearly two decades, Australia’s policy mandating the detention of boat arrivals in offshore processing centers has sparked criticism and condemnation from international allies and human-rights organizations, as well as from a wide variety of domestic groups.

While the number of spontaneous arrivals dropped off after the government introduced hardline interception policies in 2013, some 2,000 people—most vetted and determined to be refugees—have remained in limbo at detention centers in Nauru and on Manus Island in PNG. Under a deal reached by the Obama and Turnbull administrations, the United States agreed to resettle up to 1,250 refugees from either center; in return, Australia would take in Central American asylum seekers intercepted by U.S. authorities.

Since taking office, President Donald Trump has assailed the agreement as a “dumb deal,” and his policies restricting refugee admissions cast doubt on its future. However, the “refugee swap” appears to be moving forward: In late 2017, the first 30 Central Americans arrived in Australia, while the first 54 detainees were resettled in the United States, with a second group of 58 arriving in January 2018. New Zealand has also offered to accept detainees, only to be repeatedly refused by Australia, which argues that the move would merely encourage people-smuggling.

These diplomatic back-and-forths are just the latest in a long line of maritime migration-related tussles that have colored Australia’s international relationships and left the fate of the arrivals hanging in the balance. In 1976, the first wave of “boat people” arrived in Australia from Vietnam, and were accepted after an initial furor. Some 2,000 refugees from Indochina followed over the next several years. The successful implementation of the international Comprehensive Plan of Action to rescue and resettle refugees in the aftermath of the Indochinese crisis led to a dropoff in maritime arrivals, but small numbers began showing up again in 1989.

In an effort to address the renewed irregular maritime flows from Vietnam, Cambodia, and China, the Labor government under Prime Minister Paul Keating in 1992 introduced legislation permitting detention of migrants who arrive in Australia without prior authorization; this became mandatory in 1994. Nevertheless, in the late 1990s boat arrivals suddenly increased, from 200 people in 1998 to 4,175 in 1999-2000 and 4,137 in 2000-01. By the 2000s, the origin countries of maritime arrivals shifted, with those from Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and other Middle Eastern and South Asian countries comprising a significant share.

The “Pacific Solution”

An inflection point came in 2001, the year of the M.V. Tampa incident. Concerned about the uptick in irregular maritime arrivals, the government refused to allow the Tampa to unload on Australia’s Christmas Island the survivors of a sinking vessel packed with would-be asylum seekers, as provided for by international law. After a three-day standoff, the passengers were transferred to an Australian naval vessel and transported to Nauru, whose government had allowed Australia to establish a detention center for offshore processing of asylum seeker claims.

The use of offshore detention centers in Nauru and then Manus Island became known as the “Pacific Solution,” whereby the Australian government persuaded major recipients of its overseas aid budget to provide detention facilities for irregular maritime arrivals. These arrangements were complemented by legislation that excised Australian islands such as Christmas Island from Australia’s “migration zone,” thereby denying migrants who reach their soil the right to claim asylum in Australia.

The government has largely justified its policy of mandatory detention on national security grounds. While the government has enjoyed considerable support from populist media outlets, the policy has been vocally opposed by refugee advocates, including many associated with churches and the legal and medical professions. Critics point to the abuse of women and children detainees who resort to self-harm in the long wait for their cases to be resolved, and hunger strikes and riots among the detainees. Opponents also criticize the expense associated with detaining maritime arrivals for extended periods—roughly AU $5 billion (US $3.96 billion) since 2012.

When the reform-minded Labor Party came to power in 2007, led by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, it moved swiftly to abandon the Pacific Solution and close the detention centers. Maritime arrivals subsequently picked up again in 2009-10, however, and Rudd’s successor, Prime Minister Julia Gillard, took steps to reinstate some features of the Pacific Solution, including reopening offshore processing centers on Nauru and Manus Island. Meanwhile, with existing onshore detention centers becoming dangerously overcrowded, the government began to move women and children into communities outside the large cities, a proposal that initially drew complaints from local residents who felt they had not been consulted.

In yet another attempt to resolve the situation, in 2011 the Gillard government entered into an agreement with Malaysia to swap 800 asylum seekers who arrived in Australia by boat for 4,000 recognized refugees from Myanmar, then living in Malaysia. However, the Australian High Court dealt a death blow to the Malaysian “Solution” before it could take effect, resolving that it was illegal for the government to send asylum seekers to countries (such as Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, or Nauru) that had not signed the UN Convention on Refugees or could not adequately protect asylum seekers. Many of the arrivals in this period were also unaccompanied minors who, according to the judgment, could not be sent offshore.

Though Australia has also tried to enlist other, primarily poor, countries to accept asylum seekers, these efforts have largely proven fruitless. An ill-fated deal reached with Cambodia in 2014, for example, saw just four refugees moved from Nauru to Cambodia, where conditions led all to decide—within a year—to return to their countries of origin.

Operation Sovereign Borders

Though maritime arrivals fell in 2011, they began rising again in 2012, hitting a new record in 2013 with more than 20,700 arrivals. This set the stage for a full-blown political crisis, and irregular migration figured prominently in the 2013 election campaign. Despite the declaration during Rudd’s second tenure as Prime Minister that those who arrive by boat would not be eligible for resettlement, his Labor government suffered massive electoral losses and a Liberal-National Coalition took power.

On Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s first day in office, he created Operation Sovereign Borders, a comprehensive, military-led strategy to stop unauthorized maritime arrivals from reaching Australia. The number of boats arriving dropped dramatically, from a high of 48 in July 2013 to just one in all of 2014, and none the following two years.

The hardline methods used, including turnbacks and towbacks, prompted a number of legal and diplomatic rows, however. Relations between Australia and Indonesia deteriorated in 2015, following reports that Australia had paid smugglers to return intercepted migrants to Indonesian waters, a potential breach of international law.

Most of the asylum seekers intercepted have been detained indefinitely in the offshore processing centers in Nauru and Manus Island, where many have spent years waiting for their claims to be processed. In 2016, The Guardian published a bombshell report based on leaked documents detailing incidents of abuse, self-harm, and trauma among the detainees in Nauru, including many children. The report appeared to confirm allegations that facility conditions constituted human-rights violations. Further, accounts of self-immolation and detainees dying from lack of medical attention raised concerns about physical and mental health care in the centers.

The offshore detention policy has faced several legal challenges. In April 2016, the PNG Supreme Court ruled that the Manus Island center was illegal, violating detainees’ basic right to liberty, and though the Australian High Court disagreed, the governments shuttered it in late 2017. Most of the detainees were forcibly relocated to alternative accommodations on the island pending a final resolution of their situation. As for the recognized refugees, some were offered resettlement in the United States under the 2016 agreement. Those whose claims were rejected have been told to return to their countries of origin.

Lessons from the Australian Experience

Considering the central role of immigration in Australia’s national development—demographically, economically, and socially—the intensity of the debate about irregular maritime arrivals can seem paradoxical, given these account for a miniscule share of all arrivals. Over more than two centuries, Australia has become the home of millions of immigrants who have lived together relatively harmoniously. And while Australia remains one of the most welcoming countries in terms of refugee resettlement, much of this has been overshadowed by the controversy surrounding treatment of boat arrivals.

Long before the current wave of hardline immigration politics in Europe and North America, Australia’s experience with irregular maritime arrivals demonstrated how easily media outlets and politicians can stoke fear about uncontrolled entries for political gain. This is especially the case when information that could put these fears into perspective is either absent or distorted, as has happened in Australia and elsewhere.

Recent changes in the name and structure of the department responsible for immigration point to policymakers’ increased focus on security concerns. In 2013 the government announced the merger of the Department of Immigration and Citizenship with the Australian Customs and Border Protection Agency, and renamed it the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. Most recently, in December 2017 the department was subsumed into an enlarged Department of Home Affairs. The role of this new entity is described as “bringing together Australia’s federal law enforcement, national and transport security, criminal justice, emergency management, multicultural affairs, and immigration and border-related functions and agencies, working together to keep Australia safe.”

Further, the Australian debates testify to the fact that migration management is rarely a purely domestic issue. Inevitably it implicates relations with other governments able to deter departures or provide a place to which asylum seekers can be returned or resettled, as evidenced in Australia’s discussions with its Southeast Asian neighbors. Human trafficking and criminal activities further complicate regional policymaking, especially when the asylum seekers originate from third countries.

A more positive lesson that can be taken from the Australian experience is that migrants and refugees can make substantial economic and social contributions. While Australian immigration policy favored European immigrants until the latter part of the 20th century, the shift in more recent decades toward diversified admissions has helped Australia become the multicultural and economically competitive nation it is today.

Sources

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2017. 2071.0 Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia - Stories from the Census, 2016 - Cultural Diversity. Updated July 20, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. 3101.0 – Australian Demographic Statistics, Dec 2016. Updated June 27, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. 3401.0 – Overseas Arrivals and Departures, Australia, Dec 2016. Updated March 10, 2017. Available online.

Australian Department of Education and Training. 2017. International Student Data: Monthly Summary, May 2017. Available online.

Australian Department of Home Affairs. N.d. Historical Migration Statistics. Accessed February 9, 2018. Available online.

Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection. 2016. Working Holiday Maker: Visa Programme Report. Canberra: Department of Immigration and Border Protection. Available online.

---. 2017. 2016–17 Migration Programme Report. Canberra: Department of Immigration and Border Protection. Available online.

---. 2017. Australia’s Humanitarian Programme 2017–18. Canberra: Department of Immigration and Border Protection. Available online.

---. 2017. Permanent Additions to Australia’s Resident Population. Updated December 5, 2017. Available online.

Australian Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs. 2001. Immigration: Federation to Century’s End, 1901-2000. Canberra: Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs. Available online.

Baxendale, Rachel. 2017. 457 Visa Program Axed by Malcolm Turnbull. The Australian, April 18, 2017. Available online.

BBC News. 2015. Ex-Australia PM Abbott Tells Europe to Close Borders. BBC News, October 28, 2015. Available online.

Cave, Damien. 2018. Why the U.S. Is Taking 58 Refugees in a Deal Trump Called “Dumb.” New York Times, January 23, 2018. Available online.

Farrell, Paul, Nick Evershed, and Helen Davidson. 2016. The Nauru Files: Cache of 2,000 Leaked Reports Reveal Scale of Abuse of Children in Australian Offshore Detention. The Guardian, August 10, 2016. Available online.

Jupp, James. 2007. From White Australia to Woomera: The Story of Australian Immigration, 2nd edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Massola, James. 2017. First 30 Central American Refugees Arrive in Australia after Fleeing Gang Violence. Sydney Morning Herald, December 16, 2017. Available online.

McIlroy, Tom. 2017. Cost for Australia’s Offshore Immigration Detention Near $5 Billion. Sydney Morning Herald, July 18, 2017. Available online.

Newland, Kathleen with Elizabeth Collett, Kate Hooper, and Sarah Flamm. 2016. All at Sea: The Policy Challenges of Rescue, Interception, and Long-Term Response to Maritime Migration. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Sherrell, Henry. 2017. The Seasonal Worker Program: Who Is Coming to Australia? Blog post, Development Policy Centre, January 25, 2017. Available online.

Sydney Morning Herald. 2003. Children of the Revolution. Sydney Morning Herald, December 26, 2003. Available online.

Theodosiou, Peter and Jason Thomas. 2016. More People Moving to New Zealand from Australia than Vice Versa. SBS News, February 2, 2016. Available online.

Yeates, Clancy. 2017. Tourism Overtakes Coal Exports as Services Drive Growth. Sydney Morning Herald, January 31, 2017. Available online.